Investing More – Less Cost

High-demand skills will ultimately change your life for good, and that is why I used hand tools for 98% of my work for almost 61 years of daily woodworking, and why I decline to use machines. Better health and a sense of achievement makes me feel not just marginally good about myself but great, and those I seek out to train mix into my equation. You see, I don't proscribe to a culture that dismisses the journey for faster, more money or says the end result is the same. It's not...the journey can never be the same and I actually enjoy smelling the real wood as much as others just love to stop and spend time smelling the roses in life.

I am not sure that talking about woodworking the way I do always connects the dots to make the same picture for everyone. So even when you do try to connect this dot to that, we, myself and most others, will usually see things totally differently. Some so-called professionals see ripping a board of 3/4" oak for even a short distance, just a couple of feet, to be excessively negative and discount the excellent exercise it provides to get the body working every single muscle and sinew there is. But it's not just a different perspective as in point of view. The whole methodology along with the way of thinking is so extremely different, I might say that there is no connection at all. As such, these opposites define how we view what we have, chosen, yes, I mean actually chosen and picked as an actual preference to do in the making of things wood. A machined dovetail is unmade by hand, so, not the same outcome as our using hand cuts from saws and chisels in any way because the machinist discounted the effort and high demand as unworthy of mention. The journey being so radically different, parallels the energy and effort of running, cycling and such as in say an *Ironman Challenge, so this is to say that the two methods should never be correspondingly viewed or confused as one and the same in any way at all. You don't ride the bus in an *Ironman triathlon.

Our hand tool journey in the making is in no way connected to a machine version of anything we do. You cannot just look at the two side by side, the machined against the hand made, and say 'Look, they're the same.' Missing out the journey is to dismiss far too much on our part as hand makers. Machinists dismiss their journey because, well, if it's machined, they've mostly distanced themselves from the demands and processes we, as hand-tool makers, not only welcome but actively seek with our very specific way of making them. That bit in between the wood stacked up ready to make and the appearance of anything looking one like the other is the most important bit. The way you make what you make provides a vehicle for critical thinking, mental acuity and dexterity, and then, too, the physical high demands in all-round exercising of our whole body. Though many try to, this cannot, must not be as merely dismissed as they would like it to be. Hand making and hand powering is wholly intrinsic to who we are as makers, but more than that, it feeds the brain through which we get our strongest sense of what's now identified as our wellbeing. For the majority, even a questionable quality in our making, still gives us a sense of accomplishment and wellbeing. Additionally, we accept that we are on a progressive journey to betterment and that one day we will be cutting perfection into our days of woodworking. We should never try to dismiss this. These cabinet drawers took me a day to make, including grooving the drawers with a plough plane and cutting and fitting the birch plywood drawer bottoms...handwork without machines makes it inclusive for rich and poor alike. I like that my working methods have democratised woodworking on a global level. Imagine that much power to the real power of woodworking.

So whereas others might accuse me of being somewhat quite exclusivistic to specialise in my advocacy for only one of the two very different and diametrically opposed methods of working our wood, I make no apologies for using a sledgehammer in my approach. Those who don't take offence will discover the power and energy of hand tools will only enhance their lives with better health, greater strength and a more approachable way to live life more wholly. It's unfortunate that my specialising in my one field draws quite frequent opposition that's frequently aggressive and can be offensively directed, and yet, my way is the more inclusive of the two ways for my more wide-reaching, global outreach. But my goal is about developing really skilled woodworking; this is what I see as the skills' development in real woodworking that everyone can master and own, but therein lies the challenge. You have to want skill to get it and most machining is less skilled, lower demand work and that's what most 'professional' woodworkers don't want to hear, whether they earn their livings from it or not or whether they just go for the economics of ultra low-skilled methods of minimalist woodworking with machines.

Even taking wealthier economies does not mean we all have access to a machining world. For every woodworker with a two-acre garden and a four-car garage or space to build a machine shop there are a hundred thousand would be woodworkers living as high-rise dwellers in London, New York City or Berlin, all of whom have a penchant to work wood somehow. Even close country neighbours in a village setting can be seriously problematic because not a single woodworking machine is noiseless and more likely extremely noisy and highly invasive. Having lived long term in the two cultures of Europe and the USA, I could expect to live on a few acres and be quite distanced from my neighbours. I can also be forgiven for thinking the American and European dream perspectives are alike, too. Knowing what I know, our having taken the time and energy to do surveys and the maths, the majority of over 90% of woodworkers could never own a machine facility to perform an hour's woodworking once or twice a week in their spare time; the reality is that that is true no matter the continent and that is why woodworking in general is a diminishing craft even if I include machine woodworking in there. Additionally, and this should never be discounted, hand work is far more physically and mentally demanding. In the culture attacking me, this is always seen as being really negative, but this physical and mental demand is absolutely critical to health and a healthy attitude to work and exercise.

Where Have All the Children Gone

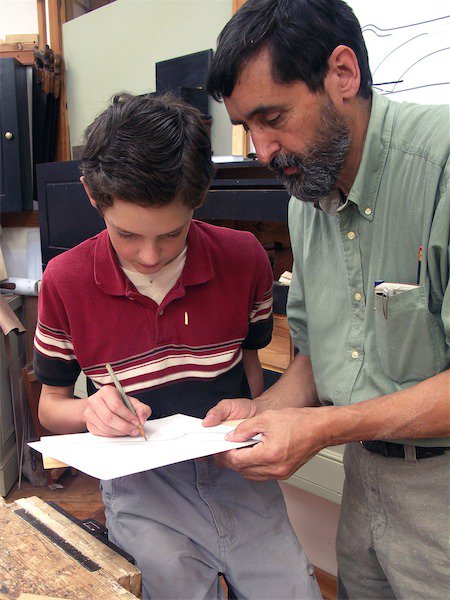

Of course, what's much less obvious to the machinist in his and her world is that machining wood automatically excludes just about all children and young people from exposure to the woodworking environment. Until they are post 18 years of age, no child or young person should be exposed to machine woodworking. And that is not just my view, either. Several entities suggest that the majority of late teenagers should be risk assessed for maturity in their ability before using basic woodworking machinery. Not all young people mature at the same rate. But if they are excluded by their immaturity, in this day and age, they will have turned to their devices and it will be hard to get them down to the wood shop, ". . . now that they've seen Paris?" And that is the saddest thing when I think to my own four boys growing up who were working wood with hand tools from somewhere between 3–5 years of age and did it every single day until they were adults and absolutely owned their own woodworking skills.

There is no question that wood machinists can and mostly do get their wood prepping done more quickly, but then, if machining is their only way of working, their family and neighbours are exposed to the highly invasive noise of tablesaws, chopsaws, planers and power routers. Switching from one machine to the other in any town, city or village setting is usually unacceptable. And then, further, their space to work, their finances and so on, would never square it (pun intended).

But it's often that others try to identify one element with the other version, thinking machine work and handwork are paired in the same area, when we hand toolists ultimately see two very different animals altogether. And it's this that then causes either a source or degree of conflict or offence that those heavily dependent on machines take out their insecurities on others. These insecurities inevitably come out in offensive, thoughtless or even mindless texts in comments on my platforms. The oft quoted saying, 'People who see anyone as different from them see them only as a threat.', actually proves quite true in this: it's not a perception attributed to an actual group of people banded together, but they are individuals sharing an erroneous perception they've allowed to develop in their own minds that unites them as a type of individual proscribing to the thoughts of like-minded people that then constitutes a class group. The concept of hand tool woodworking carries no threat to any machinist's world, and that's simply because the amateur never intends to compete by selling their work in a competitive market of commercial making. That being unquestioningly so, how could it ever be a challenge? As a group, we amateurs have no desire or way of competing for just about anything associated with machine manufacturing. Many accusers use all manner of terms to cause argument, when in actuality nothing I do bears any weight to challenge their world. The wonderful thing about my teaching and raining through project builds is that any machinist can do them their way with machines if they want to. On a global scale too, there are really not many cultures that could even possibly adopt their way of making, even in the more affluent western cultures. More and more, I find people threatened by my output to gain support by my belief that the benefits of handwork far surpass the limited gain from merely machining wood and obfuscating the outcome of high demand skilled woodworking by hand always demands. In other words, the kind of criticism tends more to deform what I say and do by adding their own concepts as input that isn't there in any way at all. Furthermore, they often perceive elements that can't be there because the shavings they say come from machines cannot be present because I don't own the machines they accuse me of using. I own only a bandsaw and so have no tablesaw, thickness planer, jointer, chopsaw, radial arm saw, mortiser. I do own a drill press, but rarely if ever use it, and I am sorry I bought it for that reason and the fact that it takes space up. I certainly would never use it on the projects we make for videos, but it is handy for metal working. I do also own and use a lathe but use it more functionally for parts like we did on the shaker bench seat 10 years or so ago or tool handles, door knobs and such like that.

You'd be surprised how many comments counter my using a plough plane to groove a twelve-inch stretch of oak or beech I'm working. They come back with some accusations after I have taken say twelve strokes at a second per stroke and say something like I'm keeping people as Luddites, living in the dark ages, or they use that dumb term Neanderthal woodworking, such like that, because of my not adopting total acceptance of the almighty power router. They make no mention of finding the right bit, installing it, setting up fences, dust extraction and then wearing the PPE and all that alongside the dangers to both the user and the wood. Oh, well!

My world of hand tool woodworking clearly identifies itself mainly with people who know that they will never own, use or have access to machines for a range of very good reasons not the l;east of which is that they are just dirt poor, have no electricity, no place to work half a dozen machines and so on. These are the intolerant ones that accuse me of exclusivity and snobbery. See how they who are often the most exclusive try to turn the tables and accuse us of what they do in their world of exclusion.

The assumption by richer nations is that everyone just needs to work smarter and harder. If they do, why they too can buy machines and equipment to make the work less of an effort and that they can all own property and a building that will house a machine shop. The second assumption then, and it is no more than that, is that this is the higher and more progressive way through its evolutionary process. A result of this thinking too is that masses of young people are dismissed from woodworking altogether because machining wood is inherently dangerous and far too dangerous for children to be involved. That being so, those accessing the ownership and use of machine-only methods no longer possess the hand work skills that deliver efficiency and speed to the work. Children and grandchildren of such oversight are therefore left outside the workshop door during that critical time of learning. The ideal age for learning hand skills is between 10–18 years of age. Rarely if ever will anyone over 18 years start a woodworking task. My sons, four of them, all learned hand tool woodworking over a period from age of 5-21 years of age. By the age of 20 they were all skilled. Learning to machine wood with half a dozen machines takes no more than about an hour per machine, more or less, depending on the machine type; a chop saw makes only one or two cut types. Square, angled and a combination that's rarely really needed for compound cuts. Nothing at all complicated, so I might allocate a maximum learning time of 20 minutes tops. A mortise machine, square chisel or a chain type, is a five-minute session of training time with minimal danger attached. A thickness planer five minutes, and it's cousin, the surface planer, maybe half an hour. Now the tablesaw for rip-cutting and crosscutting might take twenty minutes, but adding adaptive practices using dado cutters and other jigs can expand the half hour training session to a couple of hours as needed. The bandsaw needs very little training but can require working knowledge for setting up the machine to cut optimally.

Everything surrounding using machines will surround safety. Machining wood can go badly wrong in a split second because a split in wood, an unevenness in the wood, a twist can take safe working out of the realm of the maker and place them or their body part directly in the line of danger. My personal experience as a long-term machine owner and user of all of these machines is that every day something will go wrong with the wood in the process of a cut. Whereas that is the case, and you will be conscious of the possibility, you might well go for a year with nothing happening. Hopefully, you will have the reflexes, anticipation and ability to prevent injury. A friend of mine lost four fingers to his dominant hand at the second knuckle on his surface planer with all of the guards in place. Just saying. If that doesn't make you shiver, you're the better woodworker.

Hand-held Machines

Hand held machines have their place in my world, I'm just not so hooked on them as most people woodworking. Because I am always on my own with a higher output to input the audience I have, a jigsaw on 3/4" birch plywood making long cuts to reduce size makes good sense for an almost 76-year-old. These sheets are twice as heavy as those made from Malaysian woods sold in big box stores. I can lift them and move them fine after sixty years of doing so, but time is a factor, considering everything else I do is handwork. I don't have nor do I want a tablesaw, jointer, planer again in my shop.

Hand held-power equipment is as ubiquitous as the handsaws and planes were in the late 1800s now as they have pretty much totally replaced them in every woodworker's garage. They come in every kind, from buzz sanders to jigsaws, circular saws to power routers; small electric machines that displaced their reliance on a diverse range of hand skills and physical input to rely wholly on push-button electric power and minimally needed energy from humans. So that's what they are, machines. So-called power tools are smaller electric motors that directly drive cutters or belt-driven machines using flexible plastic belts. They all work on a rotary mechanism to develop cuts like static machines do, so I simply refer to them as machines.

These machines have their place, of course they do, and nothing beats a power router for putting complicated moulds on the corners of wood and especially on end grain; that's whether for a mass-market level or then just a short length. Using a moulding plane takes a greater level of body-power input and acuity stroke on stroke and whereas ramming a power router against its guiding reference faces, the underside of the power router and the fence, the moulding plane is all about what we feel through the plane body, the cutting edge and such. Of course, the moulding plane ultimately has two reference faces to register the plane to in the end too, and therein lies the key difference. The final registration where the two stops register on the moulding plane do not register at the same time; it's the absolute last stroke where the two wooden surfaces bottom out and the full width pass of the whole mould removes a shaving far wider than the plane or the mould being created happens. Whereas the power router removes stock in particles by the thousands, a moulding plane might take no more than 20 shavings to get down to the final level and the shaving on a 3/4" wide mould, might, if you measure the contours in hollows and rounds, be an inch and a half or even more. But with this machine, both registrations, fence table or platen register at the start of the pass and pulverise the wood to facilitate a constancy in forward movement. Two very different animals.

*An IRONMAN Challenge comprises three events as a triathlon. It consists of a 2.4 mile swim, 112-mile bike ride and a full marathon of 26.2 miles, so a test of extreme physical and mental endurance. The intention is to prove that anything is possible with determination and training.

Comments ()