Auger Bits and Bytes

Thinking about auger bits translates me back to a strange link we might none of us be aware of in the day to day, but at one time it would have been a godsend to certain cultures and so too today's world where spiral elevators are used to raise solids and liquids from one level to another by the twisting of an auger. The twist and turn known now as a spiral came to Greek culture as an elevator to lift olive oil from one level to another. Since then, industry has adopted spiral elevators for its small footprint and its efficiency in production. In our world of woodworking, auger bits know no equal, whether that's in the ubiquitous drill twist bit used in drill-drivers at high speed or the auger bit powered by hand in a swing (bit brace USA) brace.

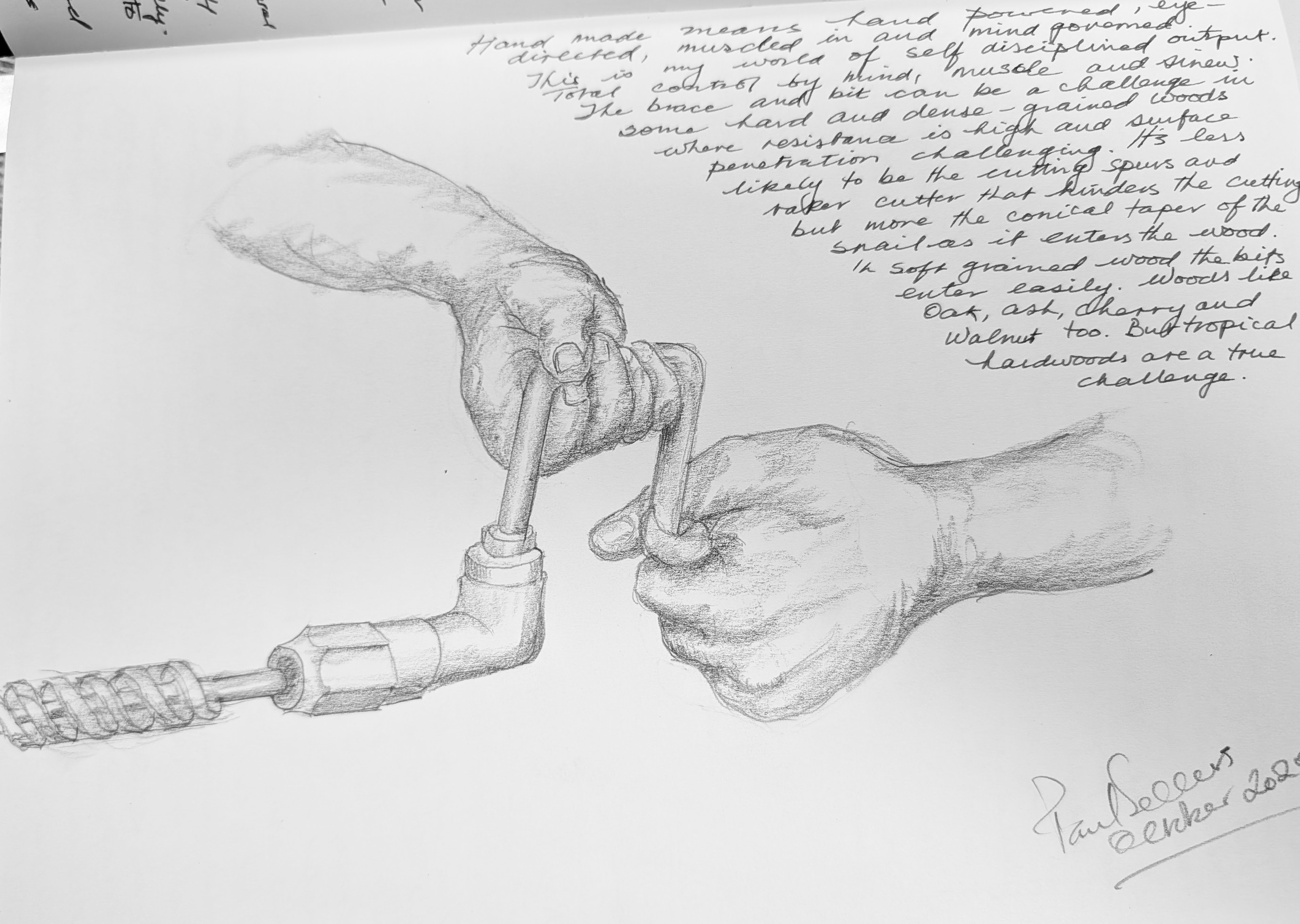

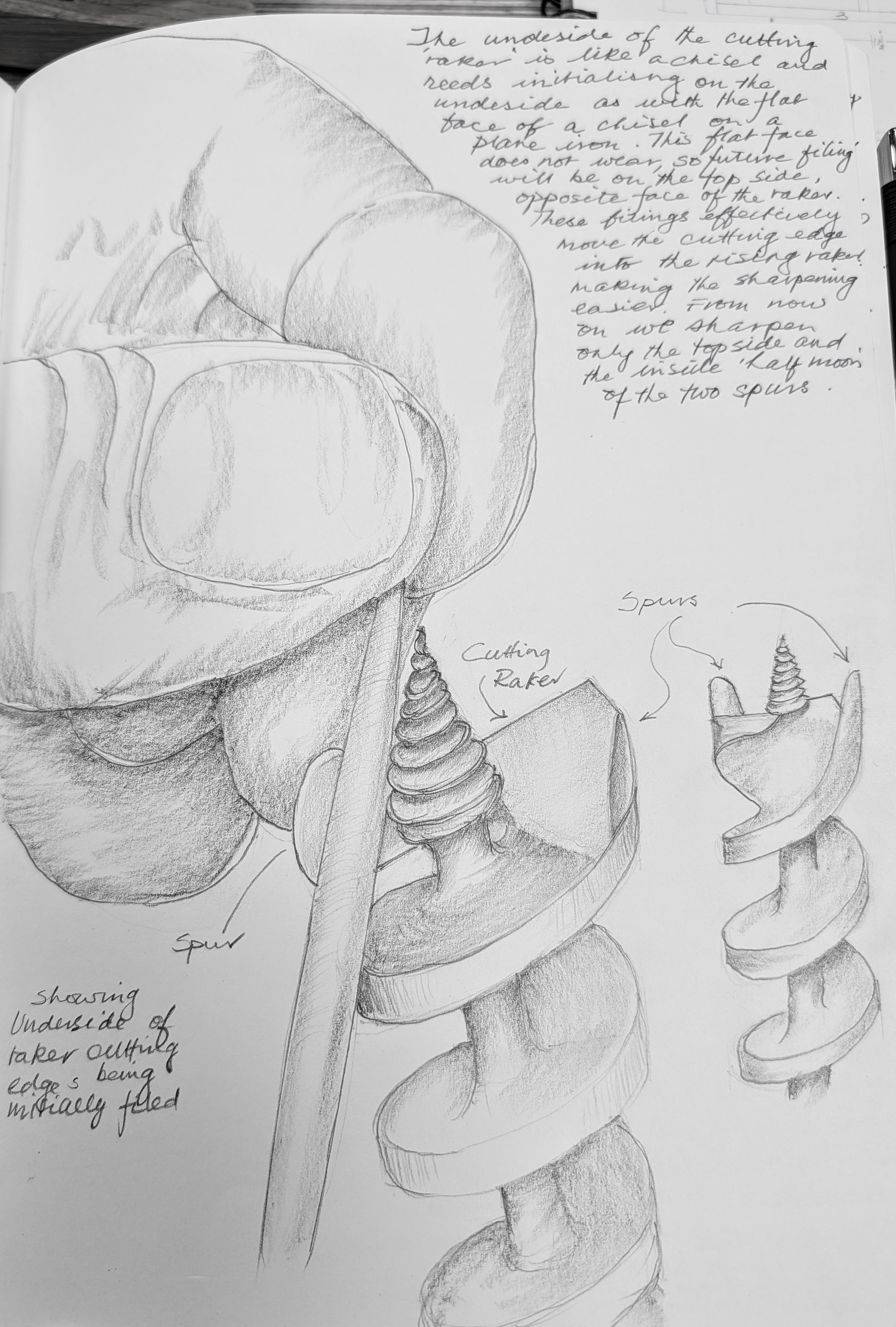

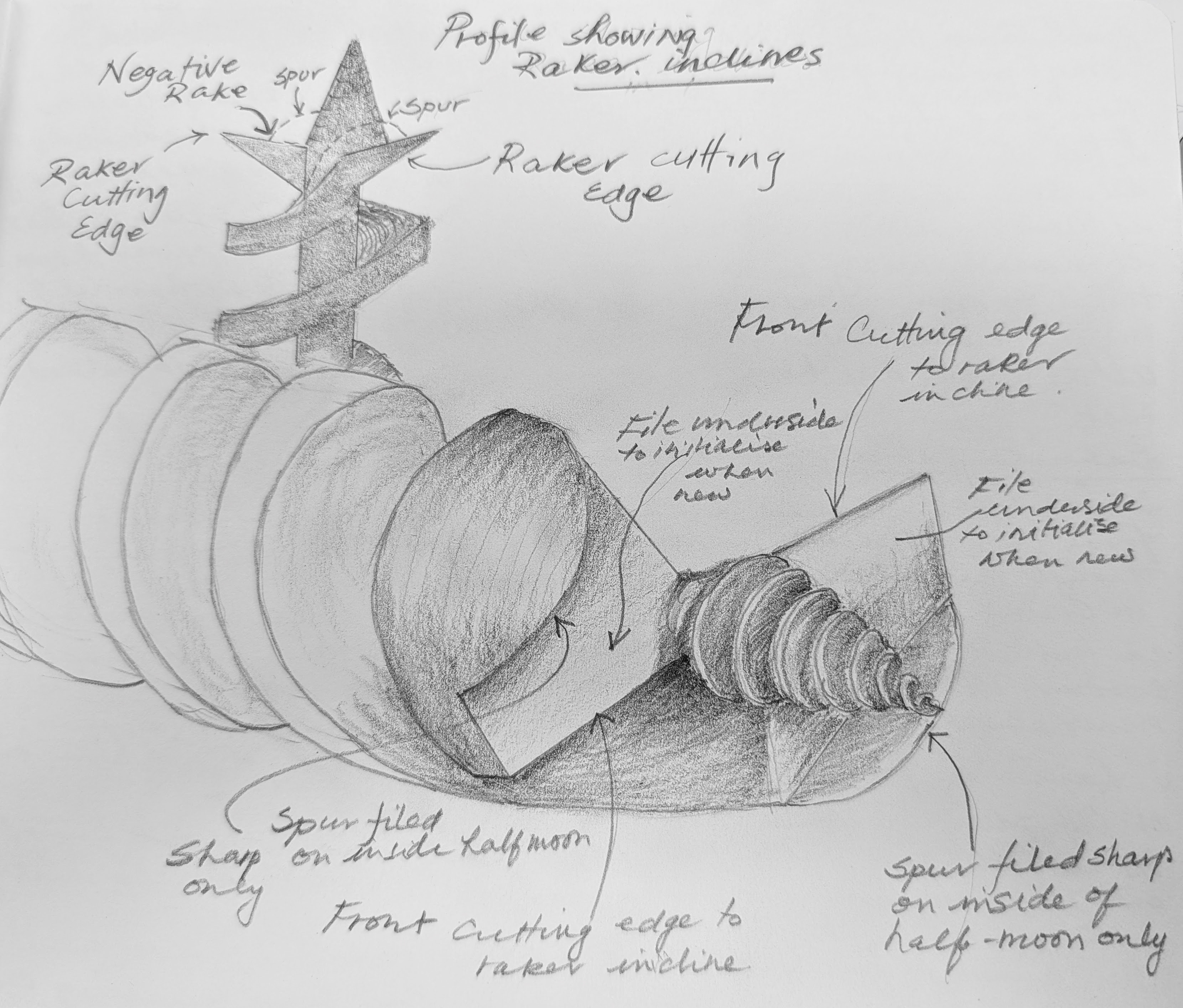

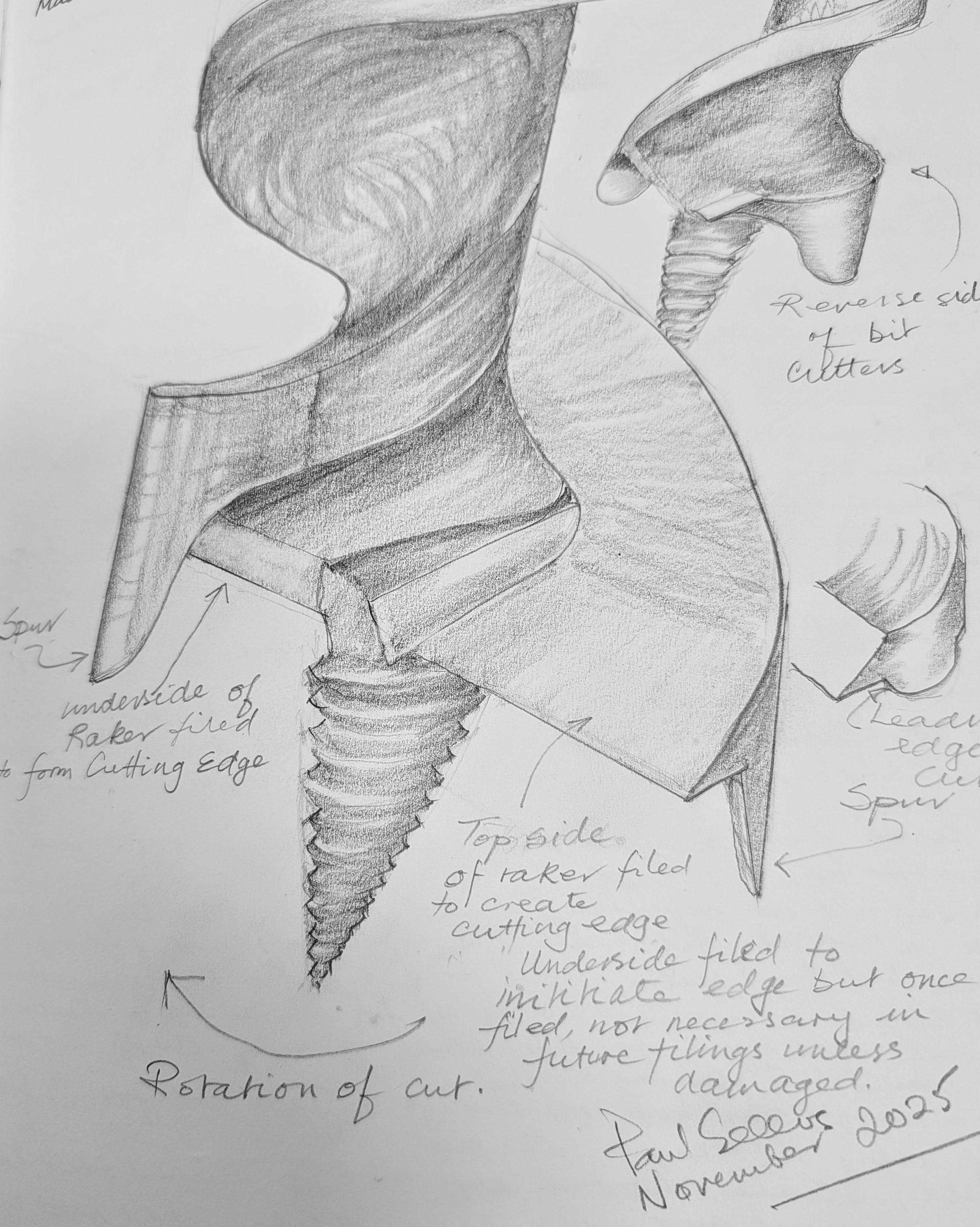

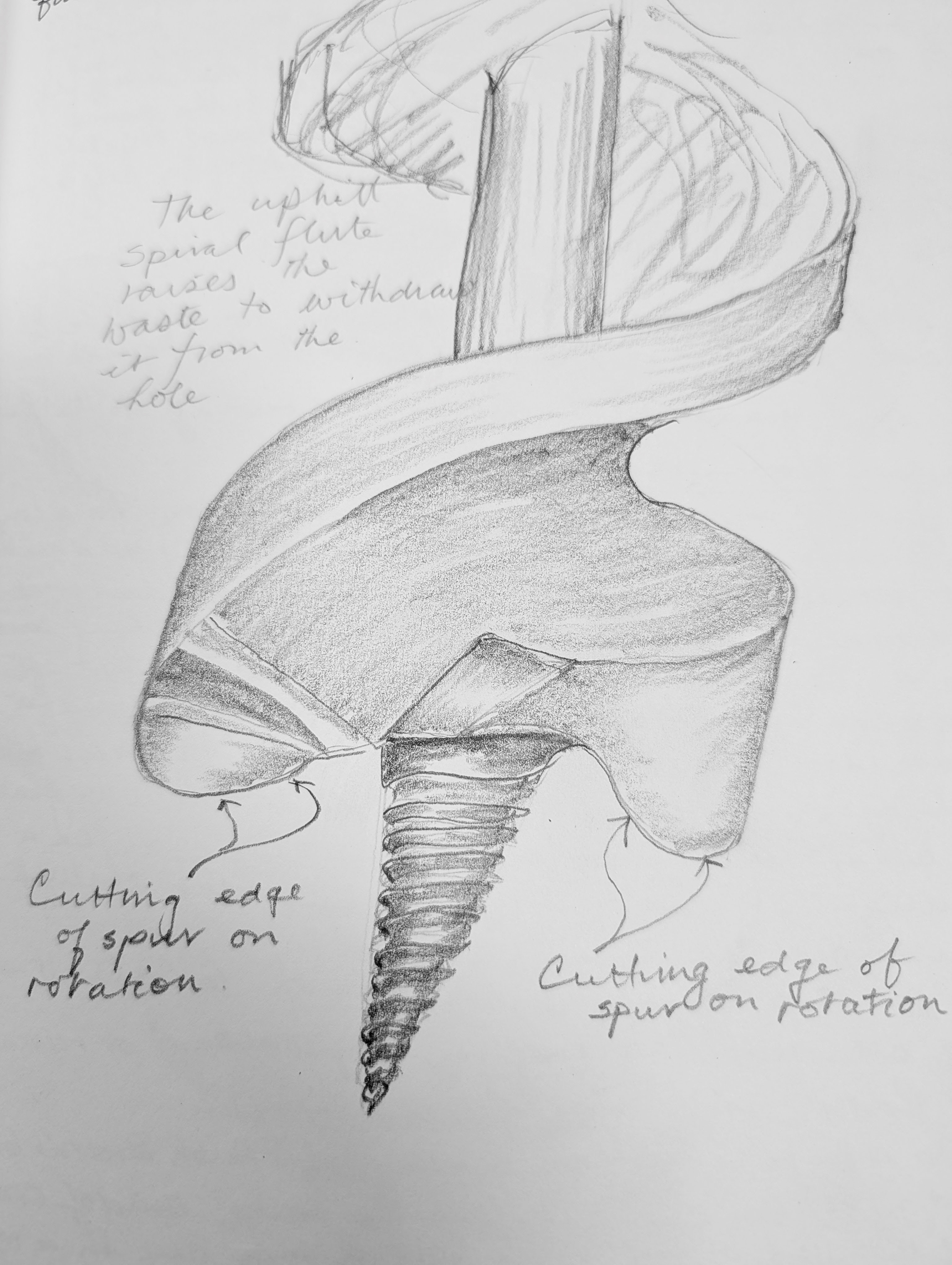

I've been drawing the auger bits recently, mostly because I intend to leave a comprehensive work combining hand drawn drawings, authoritative and knowledgeable text interspersed with some prose and a poem or two for those following in my hand making shoes in a book form.

There have been many bits made through the centuries, but few match the economy and efficiency of a well sharpened auger bit with a brace. Why do I say this? Well, for an electric drill to drill a hole of like size, say 1" in diameter, it will likely take several hundred revolutions whereas with my swig brace and a well-sharpened 1" bit it will take a steady 16 revolutions using no more than my body energy. Now, my comparison is not intended to cause argument. I do recognise the ease and speed of the electric power, whether battery driven or wall plug.

I'm writing this from my journalling records. It's mostly about sharpening and staying on top of the bits we use. A dull bit is hard to use and tears the rim of the hole with the torn fibres extending into the surrounding wood we want to be pristine and crisp cornered. Sharpening an auger bit need take only around a single minute, no more than two if you have indeed been neglectful or even hit a nail. I felt so much about this that we went ahead and made a video to show precisely how it is done rather than just tell.

I have spoken of the real value drawing brings to any craft. Almost anything and everything should be drawn and no matter how crudely yet most people dismiss the idea out of hand because, well, "I just can't draw for toffee!" Here is a reality, though. I have observed and learned that even a bad drawing isolates identifiable information and knowledge we can draw on going forward. A stick figure conveys valid information we can recall when needed. More than that though...drawing helps us to remember and at the same time equip us to look at things differently, even critically, without it becoming legalistically negative. It takes us beyond mere points of interest or entertainment and into realms of retentive value long term. You'd be surprised how many woodworkers think that dovetails are compound angles until they draw them out and then the penny drops.

Writing too helps to clarify what we see as we draw:

Mostly it's the subtle glances of light

the bending reflection in glimpses

light against darker and then in shading tones

rarely capably described in educating subtleties

of passing on knowledge

and there we see the grace of utility

a made tool where spurs and rakers work

side by side in tandem to sweep

a rotation made

a ring-cut surface encircling before

and the inner cuts follow unquestioningly

to lift out the waste where the hole is cut

There's an interconnectedness uniting sight, sound, diverse areas of feeling and so on that then unites growing knowledge we express all the more fully by writing and drawing. By my drawing alone, I better understand the auger and the brace. I dismantle and reassemble the ideas the inventors had solely with my eyes as well as by removing parts when multiple parts are used. The fascination with the auger bits is the development of a near perfect spiral from a single piece of tool steel. I once watched a skilled metalworker twist a dozen auger bits from flat pieces of steel, using his eyes for uniformity and aligning the twist in a matter of a minute or less apiece.

Sharpening was once the commonest of all woodworking tasks at the workbench. Every man could sharpen any kind of hand tool that needed sharpening. They could do a saw in five minutes and ten if setting was needed too. Plane irons and chisels were under minute and so too scrapers, axes and such. A large or even massive sandstone wheel stood in the corner of the shop, with the stone rotating through a cast iron bath holding water to swill off the steel and keep the whole cutting-edge cool. A single rotation of an 18" wheel restored the cutting bevel ready for honing, and an upward push into the rotating wheel created the camber men relied on for strong bevels. There would be no burning steel and no sophisticated jigs to guide. The man's eye held a bevel to angle full-width to a four-inch wide wheel; two-hundred years ago and for two centuries and more it was simple, proactive, efficient and economic. Progress changed all of that top make us feel superior. The head of Google recently commented that if we hadn't had progress we would never have had the Industrial Revolution, and we'd be relying on hand work alone. Hmm!

Comments ()