Dimensions to Vocational Calling

The gift notion of my possibly becoming a maker came to me in 1963; it's taken a lifetime to achieve my ambition. Of course, that does not mean that it is only achieved late in life. It simply means that the journey had the power and dynamism to start it, to begin the journey, and you find that it is just as dynamic as you progress, and it's still there at the end years too. Since that young start, I have lived to be creative in my everyday life. In that one long-range development, I would say that I have been thoroughly successful.

Fortune and luck have nothing to do with it. Most of my making was to work through hard times, take on two jobs when needed, change direction for a season, struggle financially, take on a period of immigration (or is it emigration), a period of being thoroughly disadvantaged by a cult entanglement of my life and work and then losing everything as a result of my naïveté except my will to recover, recoup and start back over. I have spoken in the past of honest sincerity and related it to my work first and then life itself in the day to day. My work rests in exemplifying my motives through the most recent decade or two. I have had a sincere desire for the preservation and conservation of my craft in the lived lives of men, women and children to perpetuate non-commercial skills of a level that supersedes those doing it solely to make money and make money all the faster. You see, there is a depth to a calling and dare I say, few find their calling as a way of life.

My work has been more rewarding to me as the work of the amateur; I blend seamlessly with those who quite simply just love working with their hands, love the concept that they too can literally own skills like mine, and then even take it beyond. Additionally, in the face of my many critics, I have disabused my audience that they must have a machine world to master their time and life. In the years and now decades that we have been teaching and training whether online or in hands-on classes, our main focus has been to dismantle wrong beliefs that machining always saves time, makes life easy and is perhaps the only way forward. I'm not in any way opposed to machine life if that's what others want, but I have now proven that with a lone bandsaw taking the smallest footprint of about a square meter in a very limited workspace, you can make everything with hand tools just fine. For not quite two decades, the wood we have used in the projects mostly came from hand planed and trued faces or, in some cases, pre-planed S4S stock. Even so, 98% of all of my wood started out in the single-car garage space as rough-sawn wood. In life, my now global audience is believing in itself far more than ever before. I don't care too much about credit for my influencing, I care more that it has worked and is now an unstoppable force in an endeavour that at one time was laughed and joked about.

My craft carried me through the decades of difficulty and sustained me and my family regardless of the harder times. Knowing my calling gave me perpetual assuredness and then respite if and when needed to face all future with full hope and faith. Cults in any faith are often difficult to actually identify. You have a belief and feel the truth of it, but somehow that belief, simple though it was or will be, can carry you away from your first love. My first love in woodworking was real woodworking, and to me, that means using my hands to make every cut using my beloved hand tools. The sharpening of saws and knife edges was something I wanted to own, as were the joints in the joinery I made, and the surfaces to wood trued with planes, cabinet and card scrapers, spokeshaves and other such tools. My faith too was simple and genuine. In the sincerity of my discovery, I simply believed in a way of life that included a greater being than one I could conjure up with my mind: one day, I didn't believe in much beyond the here and now and the next I did; I believed in possibilities I had never dreamed or thought of. I had already begun my journey following a path that uniquely influenced everything I did in my life and with it, but not so much only how I lived my life but even what I made and how I made it. My reasons for working no longer revolved solely about making money and paying bills, but the how of how I worked. Deciding not to work for money again didn't mean I didn't need to work for income that would enable me to pay my bills, it was that work is or should be a vocational calling, no matter what you or anyone else says. I had chosen to follow that calling at age 14 though I would not have described it at that time that way. At my age now, 76 in January, I know that I was called to this craft and adopted other crafts along the way. The outcome of my six decades making now is my fulfilled life, even though there are still some years yet to come to still fill with good things.

In 2009, after two decades, I found myself being dismissed from an American cult in central Texas that caused great travesty in my life. Landing back in the UK, it was my chosen life that sustained me, both in my faith and my craft. I have no regrets living and coming to know life and the people in and of the USA. How often have I said here and elsewhere that mostly, in life, you must see what something is not to see what it truly is, and you must see what something is to see what it is not. My life teaching began right before my life joining a group I believed would carry me forward in a mentoring way. During that period, I lived my belief in every way. I began writing, experimenting, studying my faith-based life and keeping true to my personal beliefs. The outcome has been my lived life now in reaching out to others to seriously consider their future and calling, be that the work they engage in, family life and faith too.

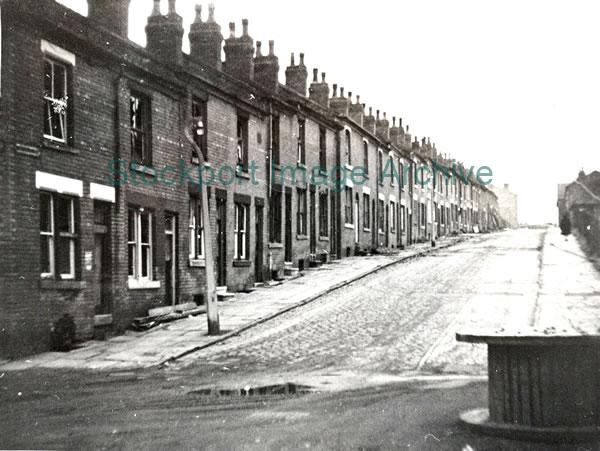

Writing my autobiography over the recent years has been very challenging. But reawakening the past can be cathartic in this one thing: life will have twists and turns to it, and even diversions can be of good value. Returning to your roots is not merely a picture depicting a handsaw and a plane on the side of a carpenter's van; a symbol alluding to an archaic past, where the carpenter of our day rarely if ever picks up such tools. It's the sincerity of your lived life, altogether the outcome of it. I recall my days with George, who taught me what school never could and included the awkwardness of fractions in imperial measuring that made me think rather than some dumbed-down method of alternatives. This complicated system enabled me to really think, but then think critically. I know it sounds crazy to have twenty shillings in an English pound sterling and twelve pennies to each of those shillings, but I can now just as easily relate to feet and inches and 240 pennies in a pound sterling as I can working in units of tens, hundreds and thousands. So, too, my faith is simple and so too my first love. I know who I have believed. The result is living the simpler life of a maker under the watchful eye of a Maker, as I did at one time in my youth, being mentored and guided by a man and mentor named George.

Comments ()