Busy Days: Discovering Wood

I know! It's the busiest of grain types; a diverse switch from any beech wood you might know because beech is not known for diversity and this wood I have chosen gives volume and depth that might seem distractive but yet, just like the mould of spalting, it creeps in to grow on you to the point that you just cannot put it down. I bought pretty much a whole tree of the wood and still have half a dozen seven-foot lengths to make from. The boards had been badly stored, hence the spalting. Six years in the wet and under a leaking tarp mid-Britain produced the reward of spalted wood, and another's neglect became my gain.

The reality of woodworking the way I prefer to do it is the reward of its deeper discovery. Take for instance science and tests; I've discovered many things about wood that tell me science has a place, but not the whole answer. Most often it takes you off on a rabbit trail that's mainly inconsequential to actual woodworking, a tangent that can be somewhat interesting, but when it comes to working its fibres it's of no help at all. Working with the wood for the cabinet above, two hundred pieces of it, planed four sides, so 800 surfaces in all, I convinced myself non-scientifically that the Janka hardness method of gauging wood hardness is mostly unhelpful. It was the same when I considered the answer in my previous post on mesquite and its workability with hand tools needing different strategies. Hardness itself is a minor consideration, and that's because additional factors regarding characteristics and workability cannot be addressed by pressing a steel ball bearing into the wood to see how deep it goes. This is where science and practice go their separate ways. it's precisely the same with machinists machining wood compared to those of us who work it with hand tools. Of course, machining wood for industry is an absolute essential now that time has moved on two hundred years. But you will never understand the idiosyncrasies of different woods by passing it into a tablesaw or power planer. The chopsaw pastramis the cuts into a gazillion tiny chips of crumbly particles and floaty dust for contamination you breathe in, but it does so absolutely effortlessly and leaves the end cut pristinely smooth and square. Not what we want, no! We want the harder, more high-demand workout because we are in constant training, like any athlete should be. To achieve good results using our hand tool methods takes considerable effort, much more than the machinist gets ,that's for certain, but in the act of working it with a handsaw, a plane, following a knifewall pressed firmly and deliberately to the square, such like that, you get both the physical and mental exercise and the inside knowledge of the wood in a real and tangible way and at the same time living and working in an unpolluted space. This alone means you will always be relating to your wood and the work very differently, and there is a romance to it that we hand tool makers just love and live for.

In preparing the 200 hundred pieces, ripping them by hand some but then mostly the deeper rips on the bandsaw, I could make a very direct comparison in my understanding of grain. Planing the same wood along its length, seeing the ripples of shavings going with and against the grain in the undulation grain always takes in beech, anticipating tearing, feeling the resistance, my knowledge far surpasses the Janka hardness test that actually doesn't really tell me much at all beyond the very merest of lesser facts.

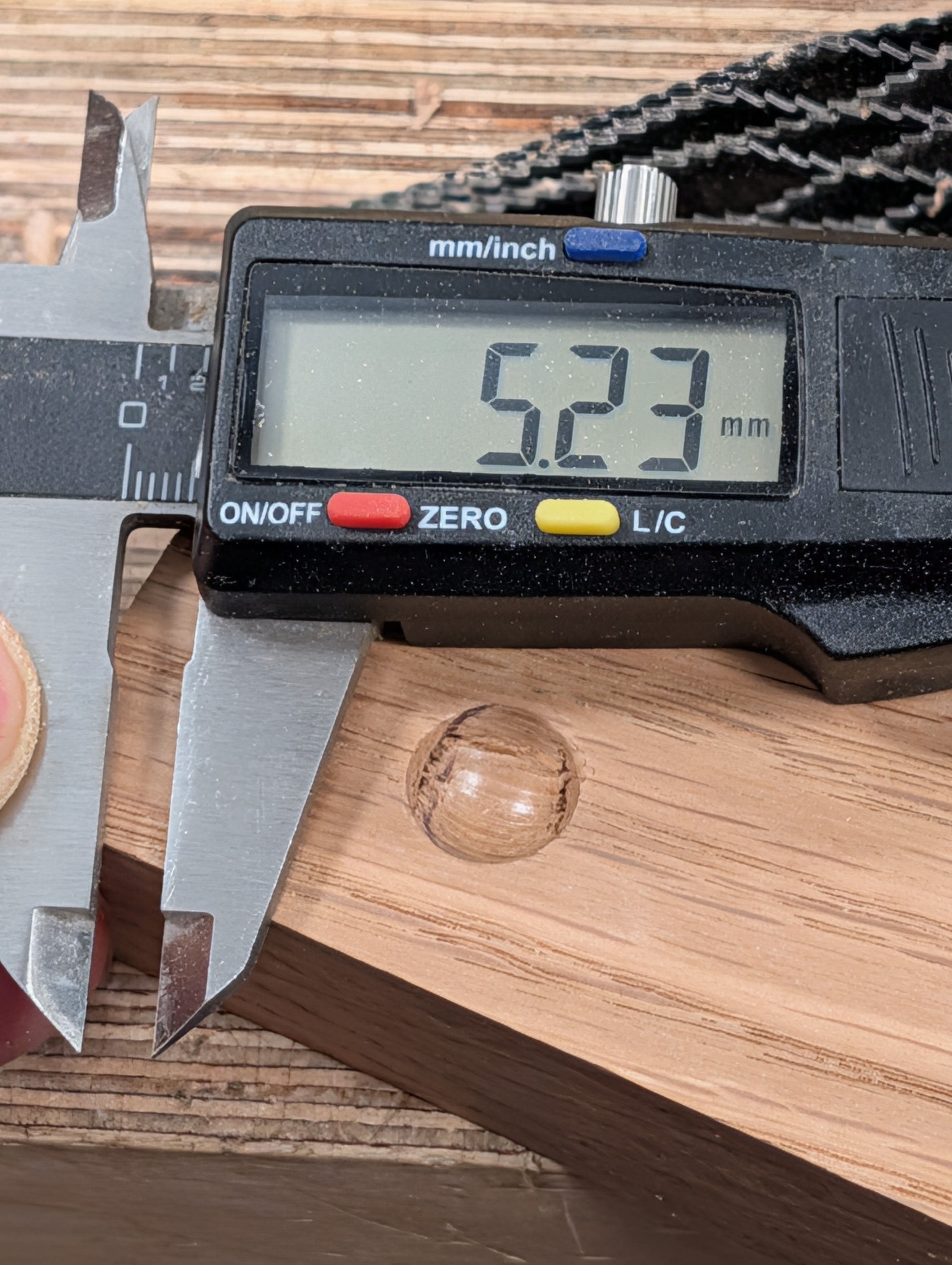

Of course, there is no better understanding to feed into your brain than trying things for yourself. I took a half-inch steel ball to sink into my experimental European oak and poplar scraps to see how the difference felt applying my muscle to the vice.

The Janka test takes a half-inch steel ball and presses it to half its diameter into the wood being tested. The pressure exerted measures the resistance to that indent by calculating the force needed to embed the ball halfway into the wood. The force is recorded in pounds-force (lbf) or kilonewtons (kN).

In machine shops, be that commercial or in the garage home shop, the cuts are very much the same regardless of the wood being cut, though you might feel or hear variations of density as you drop the chopsaw or push the wood into the teeth of whatever saw you are using; though this too is some minor measure of knowledge, it's never the depth of measure attained through working with hand tools. The issue for me is the distancing that takes place using machines of every kind. The sensation of machining, the vibration, the noise, the dust and so on, separate us from the work. In some ways, I might liken machining wood to seeing it more as a sort of video action where the process is so fast your whole mind is radically distanced from the process to such a degree the work is somehow ghosted in the whir and blur speed always leaves you with. It's a time-lapsed production that cannot really be processed fully and leaves 95% of the information out. Think passing cars in close proximity on motorways, the thwacking bullet from a gun and the hole in the target a hundred metres away from you... .01 seconds from gun to bullet hole depending on the firearm and bullet type.

Where some critics diss the process of hand tools as inaccurate and slow, in their dissing mode they miss the reality that the speed slows down the process to thrive within a speed that we can actually process the work, understand the wood fibres and retrieve valuable information to store and keep long term. These facts are mostly missed when we are young, dismissed when we are in the mid-years, and lost altogether in our older golden years. How often I hear the lament of men my age and a little younger saying how they missed it growing up, and, oh, how they did miss it!

My pare-cutting, applying even forward thrust and light downward pressure from a newly sharpened edge peeled away the wood full width to an even thickness and when I offered the wood to the mortise it was ready to be tapped home against a perfectly chiselled, gap-free shoulder. The Janka offered me nothing of value.

The plane has always given me revelation about grain structure. In the same wood from the same board, the density of the wood shifts markedly but is the varying resistance due to grain undulation, grain tightness, mineral deposits in the wood, spalting and so on. The fascinations keep me engaged. I stop to answer my questions in the moment as I do the accuracy of my planing a square edge when the shoulders don't quite seat dead square across to both shoulder lines. And what of friction causing the development of scudding, the sticking saw. Why did the tools work so deceivingly well one way and then deceptively badly the other when the two courses are but inches apart? Go ahead. Pass the same wood into the planer and tell me you have the same information I gained. And more than that. My muscle knows no excess. I have developed muscle and strengths that actually match the needs of my work. My arms, pectorals and shoulder muscle are trained by the work I do. They have been fully developed and held to for 60 years through the practice of real woodworking. I can't afford an excess of muscle. I doubt that I would get through my day if I did.

Well, here I am. I'm still the amazed man stunned by the busyness of my wood and the way information comes to me in the working of it. My methods were and still are in this day the technology that still works for anyone prepared to spend a few hours and days extra in the mastery of skill. It's an unfolding future that just keeps stretching the mind and muscle in mental and physical ways, and I am just off to start another day in the shop.

Oh, and you are always welcome to join me in owning your skills long term if you'd care to join me. It will be free, of course. Woodworking Masterclasses and Common Woodworking are still as free after all these years. Free woodworking education at its very best. Free? Imagine!

Comments ()