It Was Method More Than Tradition

Making drawers utterly by hand takes mastery, there is no doubt in my mind. Establishing patterns early on in your making strategies ensures speed and accuracy. For my drawers, I needed 5/8" stock but could only buy in 3/4" material preplaned. But preplaned did not mean trued, square, uncupped and untwisted. It simply means that for general construction work you could force it flat with air-nailed or lengths wedge and fixed otherwise. For drawer making , I knew I would need to rework every stick and stem.

First off, I planed out the humped sides of the pieces to establish flat surfaces on those sides, and then focussed on removing twist. Every piece had twist large and small. Cutting them near to length and width minimised exaggeration ahead of the work, so crosscutting and width cutting is always essential when everything you do is by hand using hand tools only. With so many pieces throughout this project, I have used a Bosch jigsaw in places. About half, I would say.

By the time the cup and twist are removed from the initial registration faces, the thickness is not too far from my final desired size. Let's discuss this first. In my case, here, the wood has a hollow of 1mm, about 1/32" give or take. That means, S4S, the opposite face will have a belly or camber on it of the same amount.

The first line taken straight from corner to corner shows the amount of the camber and then, on the opposite side, the hollow. I will plane to these two lines for a flat cross-section to show the reduction of stock. Remember that you cannot sidestep this remedial work. If you do, you will be fighting the wood all the way.

Setting a marking gauge to the 5/8" thickness and running the gauge lines along the edges and ends readily establishes the guiding lines to plane the opposite face to. I'm not obsessed about dead thickness, though. I use my head when using all my own muscle and sinew, adopt a more practical perspective. Adding or subtracting a half millimetre either way is not too much of a difference but more my own accepting and deference of it to me. i'm simply prepared to work with it and make adjustments others will never notice or know of or see in the end result. Parallelity is usually critically important, and I aim for that, but I can even fudge there if I want/need to. In such cases, I count plane strokes here and there as I plane, knowing without checking that I am indeed as humanly parallel as possible. These small guestimates always work for me now after all these decades, and they are fast. Ultimately, my end product is comfortably progressive in the making and doesn't put me on any kind of conveyor belt.

My hope for now and my future is that I always have the strength and the ability never to resort to more than the basic 16" bandsaw I already own in my workshop. Using power equipment like tablesaws and power planers over maintaining muscle and sinew is not in any way a progressive option for me. I want the maintenance of high-demand woodworking for both my mental and physical health. Muscle power for work-strength mental acuity are to be the real power of my version of 'power-tool' woodworking, and these two must be under constant maintenance. The minute I take that easier machinist-mostly path will be the day my muscles start to atrophy. The maxim "Use it or lose it." is never truer than in woodworking. That hand-eye- coordination should never be taken for granted. Even taking a few weeks off takes its toll, and it might just not be that easy to get back. I can't risk going to machine woodworking only as a work model beit wholly or partly. That type of woodworking belies my belief that handwork is the only way to preserve true skill. But to those who already have physical disabilities of any type, do not feel condemned! In my view, disability is rarely a choice, and you may well have chosen your best or only option to keep working your wood.

My end-grain square-end planing on all of my pieces came from freehand planing using only my #4 Stanley, the one I've used for 60 years of daily woodworking. I did not use any guides or shooting boards. With this plane, I may be on my sixth or seventh cutting iron, even though I rarely ever grind the bevel on any mechanical grinder. The plane owes me nothing. I also might use my #5 jack plane but less likely so. Would I not choose or just use a bevel-up, low-angle version? Not usually. One good enough reason is the sheer weight of these planes. Too many planes on the benchtop and surrounding surfaces and shelves just get in the way with not enough benefit. The weighty versions, which is all of the modern bevel up planes are, are in the way even more. Keep it simple but keep it sharp is my mantra. I'm thinking that I might sharpen about ten times sooner than most of the woodworkers I have ever known, including those that taught me as an apprentice. Advocates for low benches to bear down on the work from overhead have never discovered the essentiality of sharpness. A sharp plane 'pulls' itself to task. Any bench lower than 38" will almost always be too low for the average male woodworker, yet almost all benches are made and sold at dumb heights like this. Low bench work heights are a back problem just waiting to happen.

With all the drawer depths from front to back the same length, I plane them individually to size, stack them neatly and then lay out the dovetail sizes on one and clamp the others with it in the vise to transfer my work lines on all of the other side pieces. The whole process of planing my wood is about two hours. The laying out is an hour or so for the four drawers. From then on, cutting and making the drawer corners is 15 minutes per corner, so around a comfortable hour's work. Why did I mention the bench height? For layout and planing my wood, the height that works well and best for me and every average height male has left me with zero back or neck pain throughout my 60 years of daily woodworking by hand is 38". I'm five eleven. 6,500 students worked at my 38" high workbenches over extended periods, and not one of them ever found the benches uncomfortable.

The double cross-check on these is to flip them end for end to see if indeed the dovetails at the opposite end align too, and they do. Any discrepancy shown will be half that difference, so in these pieces I am a mere .25 of a millimetre out.

The uptake of moisture causes more distortion, as you can see in the top two pieces here. This shows that the wood absorbs moisture from the faces. Before I start the dovetails, I will stand these on edge, and they will go back to flatness before I begin.

The first drawer came together perfectly once the wood was reworked to final size. Cutting all four dovetails was around 15 minutes per corner (with five dovetails) apart from the filmed one which takes longer because of filming and the necessary stops for filming needs. The drawer bottom, grooved by hand, took me about 15 minutes, and gluing up about ten minutes more. You must move very quickly with five tails in pine as the wood surface fibres being glued swell rapidly and any slowdown can prevent the joint from going together.

Working methodically is critical to peaceful working, and especially is this so with handwork. I sharpen my tools dozens of times to get the enjoyment and pristine surfaces I strive for throughout my workday. I still sand, but keep my sanding surfaces to a minimum by using hand planes. I think my sanding is reduced by between 80-90% just by hand planing. That's quite a time saving, and that's what makes me efficient. Sharpening and reloading a setting the depth and alignment of a plane iron takes about two minutes each time.

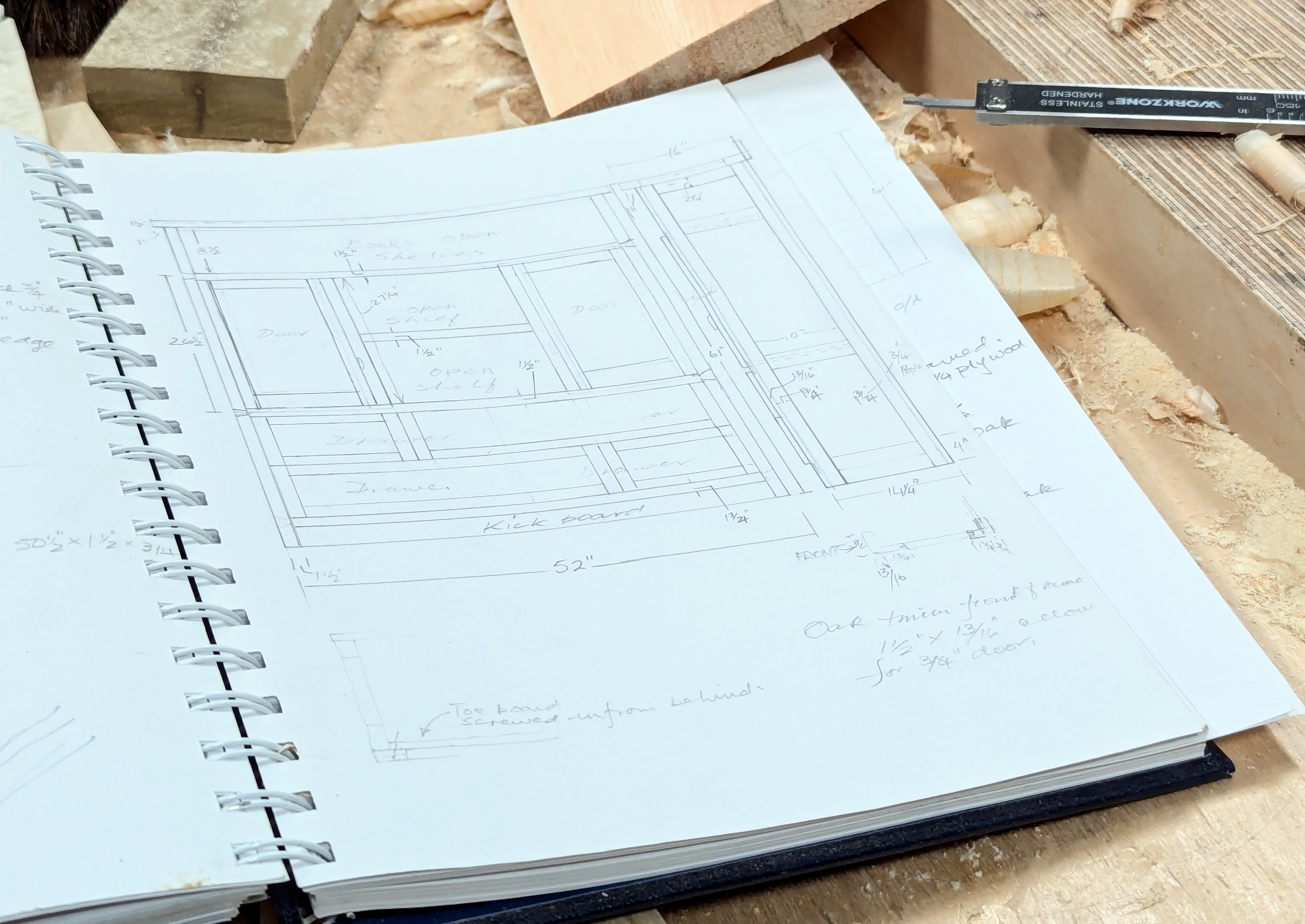

Drawing out to scale on paper at my bench is time-consuming, but it is also a record keeping task that is priceless in my making. These bench journals of mine go back decades and are quite an archive. The note changes I make along the way, for some aesthetic reason and then too corrections and such.

I'm in the last throes of my latest project for Sellers' Home bedroom series. You can join me on sellershome.com if you want to catch up with what I originally called a houseful of furniture. I am closing in on my fifth year of the project to build a complete houseful of furniture. For such a small entity, this has been a massive undertaking to do without going for sponsorship from other businesses. We have financed the whole venture, including buying the house and having builders in for most of the three years on and off as needed to bring everything up to date. I'm still not sure how we did it.

Comments ()