A Day Like No Other

Going into wildness alone is a high-demand aspect of my personal woodworking journey. Would I do it now, now that I am nearing 76 years of age? And would I do it as back then, without a cell phone, when cell phones were yet to be invented, and the internet was still mainly in the birth canal or at least still in the crib of evolution? I worked on the premise that I should try as best I could to expect the unexpected, plan for it, but that it could not be a risk-free, self-entertainment enterprise. I had a family to feed with only my income to support my family. Irresponsibility and total responsibility for me went hand in glove. No one else would take care of my family should something happen to me. I was going into a dangerous environment frequently. This is not living in the Greater Manchester, UK jungle I had escaped from, where my formative years had very much disappeared. Still, it did demand all the more survival skills that the city life never altogether prepared me for. 41º by noon was a heat I'd not yet experienced before Texas summer peaks. You didn't dress down in a tee shirt and shorts to go into the environment I was going into on that day. You didn't wear Ray-Ban, Oakley or Maui Jim (Don't worry. . . I had to look up popular named brands as I have never worn shades in my life) sunglasses for image, nor split-knee jeans to vent your knees for a cool look. This prelude was to harvest free wood that cost you dearly. Stout boots and thick blue jeans worked best, as did long-sleeved cotton shirts and a covering for your head and neck nape. This was this woodworker's lived life. Carrying two days of drinking water, a couple of day's of emergency food beyond just a pack lunch just in case and a spare chainsaw were all mandatory, as were a shotgun, a side arm, an axe, a half decent knife and petrol in a two-gallon can. Things go wrong when you are not prepared and especially when you are alone. No one in their right mind volunteered into joining you for harvesting mesquite trees in the summer heat of Texas.

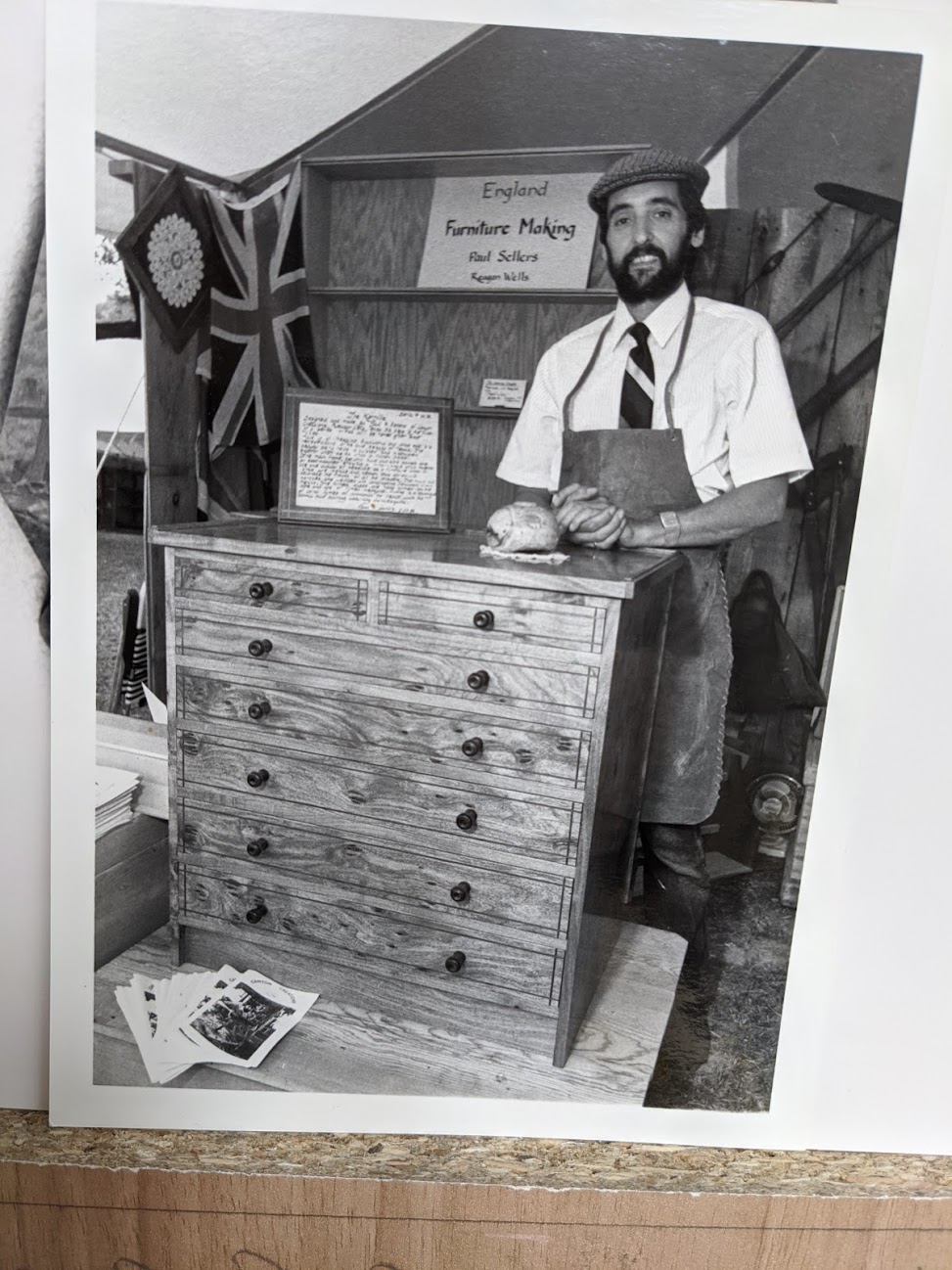

My life in working wood began with working hard and diligently at what I really loved the most and something that could never bring gain from any life promising ease, a swimming pool and a couple of fancy cars alongside a one-ton monster Ford dually. At fifteen, play and school totally ended for me, and I became a workman and a working man. The men I worked with made sure I knew that I was not even near the bottom rung of the career ladder. Nevertheless, no matter how it began, I actually chose to do what I was doing. In my starting out, much of my work was labouring for others; I lifted and stacked a thousand beams, swept up sacks full of shavings from around the men's benches, moving pallets of wooden parts from one machine to another. Grown-up work. My work from that point was something that would ultimately take at least half of most of my future days as a maker, designer, teacher and influencer. It's been a way of life to make my living from, but the important point is, I chose it and I preferred it as a more demanding way to go. Woodworking, really furniture making, and with hand tools, opened many doors for me when for all others I ever knew it was closing. Over a two-decade expanse of realness, I moved myself forward, away from any luxury and on into hard work and long days. Here is a brief extract from my journalling and notes:

Monday, August 21st, 1989

The fine, lightweight, panel curtains billowed in a welcome Texas breeze as I left the house for my truck. Already I had begun to sweat, but the feint intake of air from the window cooled me the instant I began my early-morning drive. Windows down, no AC, my Texas remoteness was something I had grown to love. Within my first few years stateside, I was learning to go without too much. I'd built my Texas home in the middle of near nowhere, and the doors in Texas opened to me in the start to a new life. My enjoyment for such gifts of simpleness never waned from that lightly lifted curtain in its draughting from the open windows. I began to live in the wilder outdoors and to live out a life forming memories I didn't know would exist in my future. Things like working my chainsaw against a backdrop of Texas longhorn cattle homing in around my dropped tree to feast on the mesquite honey-bean sweetness amidst the crushed branches that came from cushioning the three-ton stem I just felled. Their horns clicked against one another now and then with the swaying of laden heads, and then too came the winding prod to another's soft underbelly in the gentle but weight jostle for feeding space. I was glad to take precautions in prepping. I'd started both of my chainsaws, changed out the chains and packed a half dozen spares in case something like stones and barbed wire were lodged in my cut line. Both saws started up first time. In 20 years of owning two 16" Echoes, they never once failed me.

The sun settles to silhouette a hundred cow backs, horns and heads twist and turn against the west horizon of its setting. I would often forget the time, many times, as I pushed myself the harder (as I always did) when time stands still for eight or more hours of my searching, lopping, trimming, felling and loading my prized tree and branches.

I lift and load alone; I'm used to many hours alone now, and in such sweltering heat and a wildness I came to know the isolation of like no other, an isolation and loneness that gave me a love for an aspect of Texas most have never seen. Strangely, the isolation gave me a newfound and very different peace as finally, I'm winching the stem with two come-alongs, a rock bar and some applied physics until it rolls slowly but deliberately onto the truck bed for the journey home. The leaf springs on my 1951, one-ton flatbed level out to dead flat and rest immoveably bedded in a way they shouldn't. I'm finally loaded and abuzz with my prize load as the red ball of sun settles to bounce on the horizon above a forest of mesquites and junipers. I'm overloaded by a half ton and then some. Oh, well––here's hoping. I have two shallower river points where I can cross without too much gravel shift above a limestone bed. None of these crossing areas are really used, and I follow the river north and south to find low banks and spreading entry and exit sides. I'm three miles from home but with no public highways and even where I am is not a road at all. Texas ranchland is too big for anything more than an economic consideration. I am on land belonging to the former governor of Texas, Dolph Briscoe, who apparently at that time owned over a million acres.

My first crossing is the deeper of the two, and the water floods in through the worn-through floorboard of my cab. This it has always done since I bought the truck, and with a full load, it's as low as it can get in the water. I listen for the gravel shifts under the heavy load as I move slowly into the deeps. Halfway across, the front wheels seem to lose most connection to ride higher from the back weight of my load and then the air in the front tyres, pivoting me higher. Without traction and connection, my steering is all but gone; I am buoyed ahead, unsteering but hoping the river doesn't turn me downstream. I'm well over halfway across and willing the truck on towards the opposite bank of this not so 'Dry Frio river', wishing it was indeed dry. My back is still sweat-soaked and stuck against my leather seat. Who knew bliss could be had this way; deep water, a truck's full load, a Texas sun setting in my rearview and a sudden climb as the rear wheels bite the gravel to climb me out of the river after thirty feet of seeming nothingness.

The chug chug of an old truck with the sounds of evening cicadas calling out settles my spirit in tranquillity like a gently beating drumbeat firm and strong. I'm lifted once more, knowing this fulfilment from a good day's hard graft was all above and beyond me. This, truly a good harvest day of mesquite cutting for me, for harvest was what it was, a true reward of provision from hard work. The wood was mine but not to burn or barbecue meat on, it was to make from and feed my family from things made with my hands––this was back in 1988 when I was 38 years old. I remember it all as yesterday but better. Who writes of such things as a migrant from England anyway?

Comments ()