Why We Chop Deeper

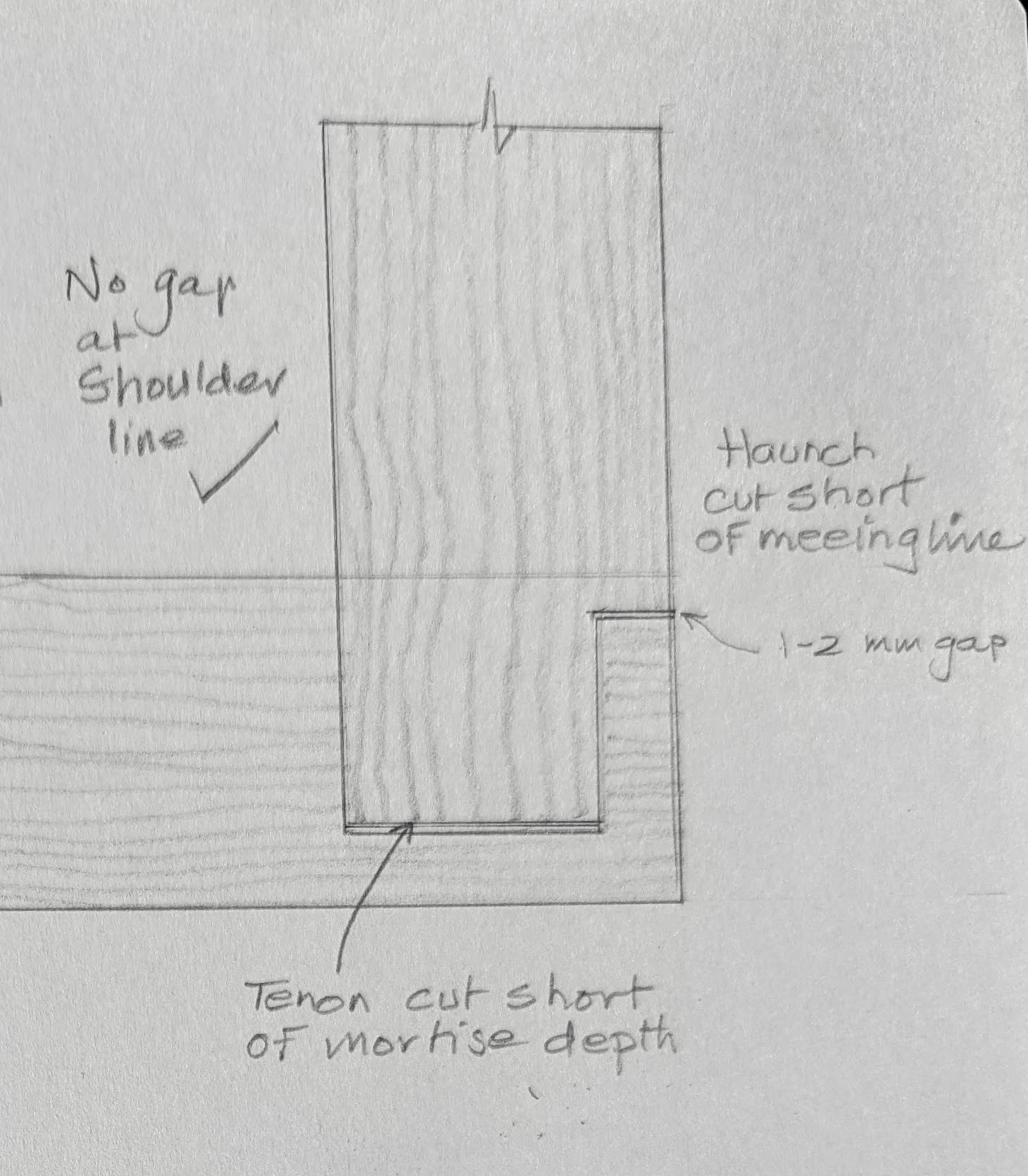

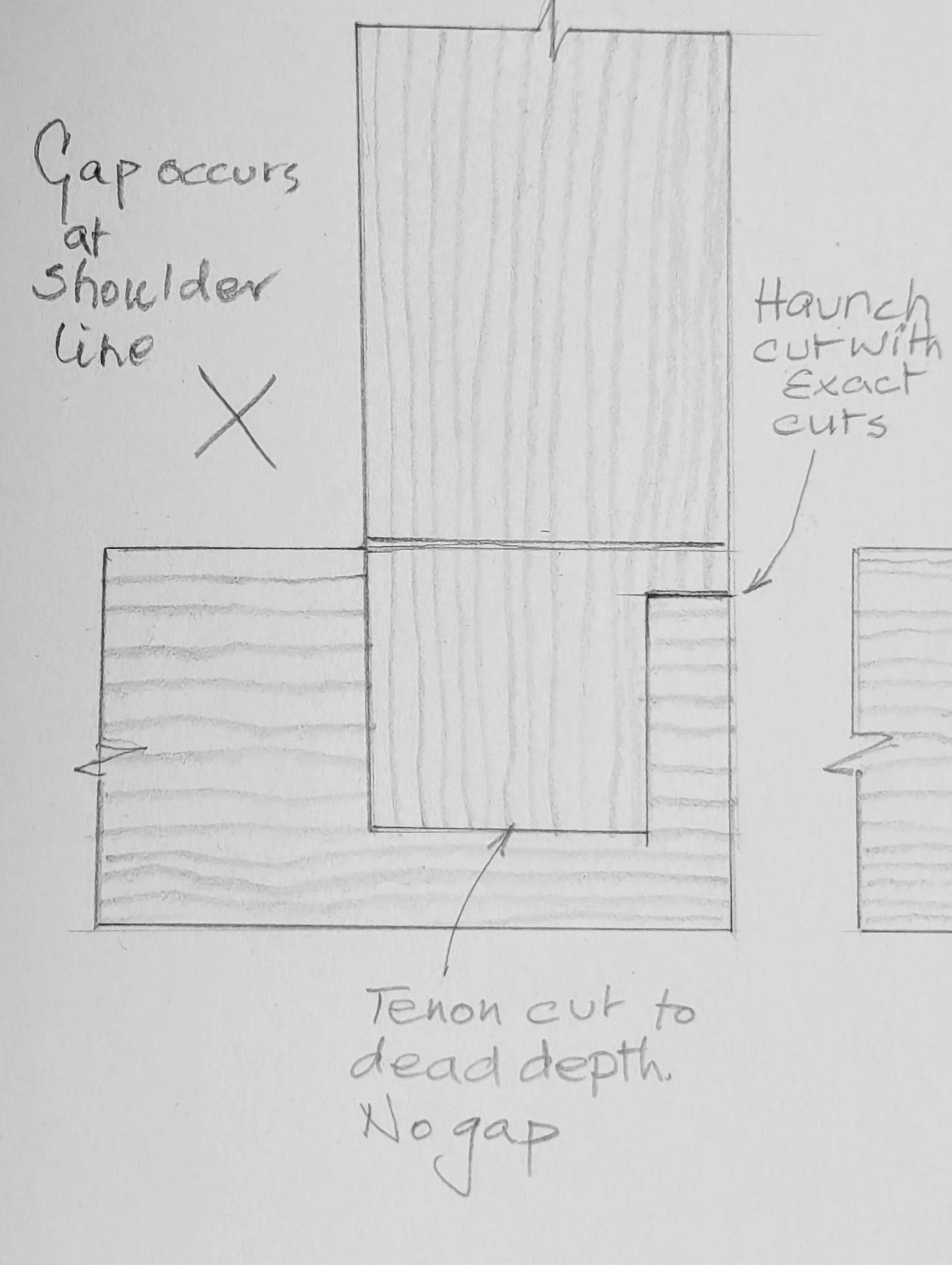

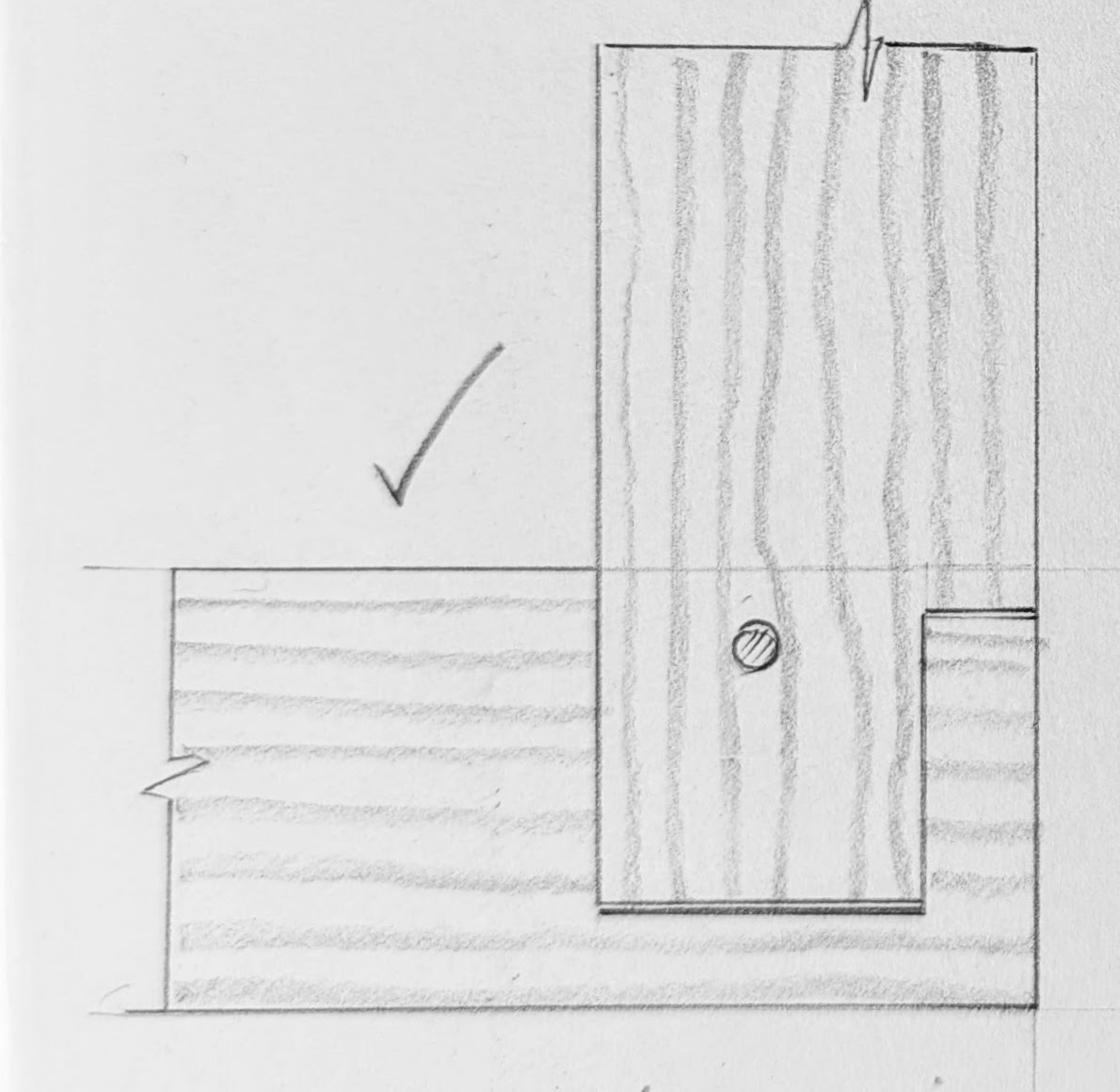

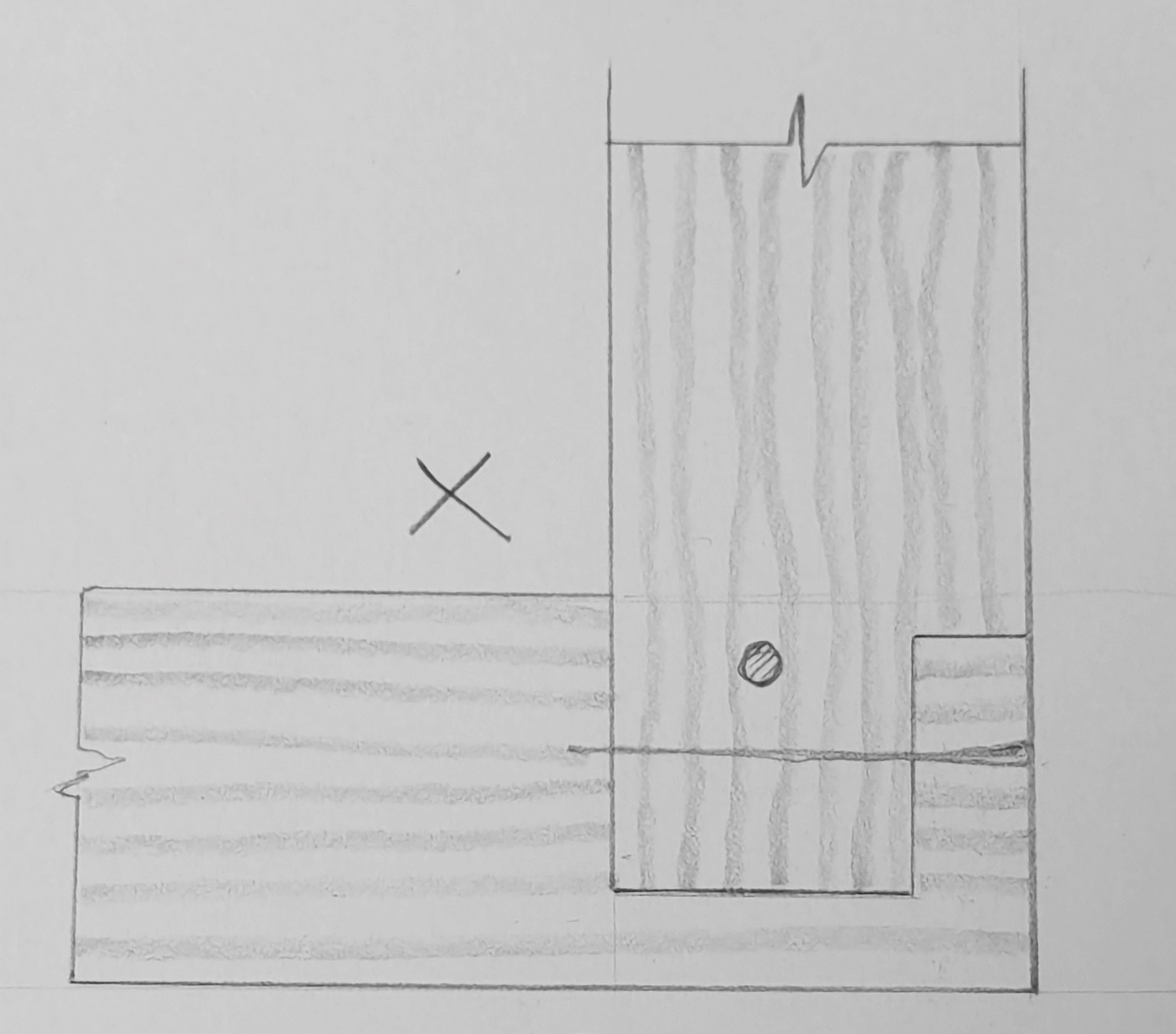

If you know me at all, watch my videos and such, you'll see me mark my chisel to the length of my tenon with a Sharpie so that I know when to stop the main chopping...but then you'll see me make another lighter pass taking the mortise slightly deeper. Why is that? Well, when the tenon doesn't pass all the way through the stile or adjacent mortised piece, we must consider possible interference through shrinkage of the receiving piece, especially will this be so on wider stiles. If the end of the tenon touches the bottom of the mortise, we could be building in a problem for later. Rarely do we think to leave a margin, a buffer zone if you will, but we should. By this, I mean we should make the mortise that little bit deeper than the length of the tenon and even consider the haunch aspect of a tenon to be slightly deeper too. This might not gel with the self-declared and so-called perfectionists. They want that tight line no matter what, even though it's not seen in the bottom of the mortise, but long term, no matter what we do, wood expands and contracts as it absorbs and releases moisture from the atmosphere or other sources––it never totally stops.

Working with George, my mentoring oversight as a boy, we talked about such things. His words, "What we do here in the shop must be considered long term after delivery. Tell me what would happen if the tenon is 'bottomed out' when we made it, but the environment it ends up in is drier?" I have never read or heard of this since that day in 1967, so I treat it as one of those trade 'secrety' things.

George always made me think for myself. He posed questions to me all day long and then waited for answers. And it wasn't just about wood but all kinds of things. He would reinforce the need to query what we did, what was happening around us and what was happening in the world. "Always question authority."

How much had been passed to him was never made clear. Owning knowledge for the main part was to take ownership of it when it was 'given' to you. This was the way of word-of-mouth learning, where seldom were things written down in text but perhaps a few lines in a drawing on a piece of pine you were working on or the inside of a cigarette packet, an envelope or whatever was close to hand.

Making an apprentice think was critical to ownership. "Why do we leave a gap at the bottom of a mortise hole, Paul?" or, "Uh oh, why is that haunch tight cut?" Thinking about the reasoning, reasoning it out, gave you better ownership of knowledge without being told the reason why. It's different. Just different.

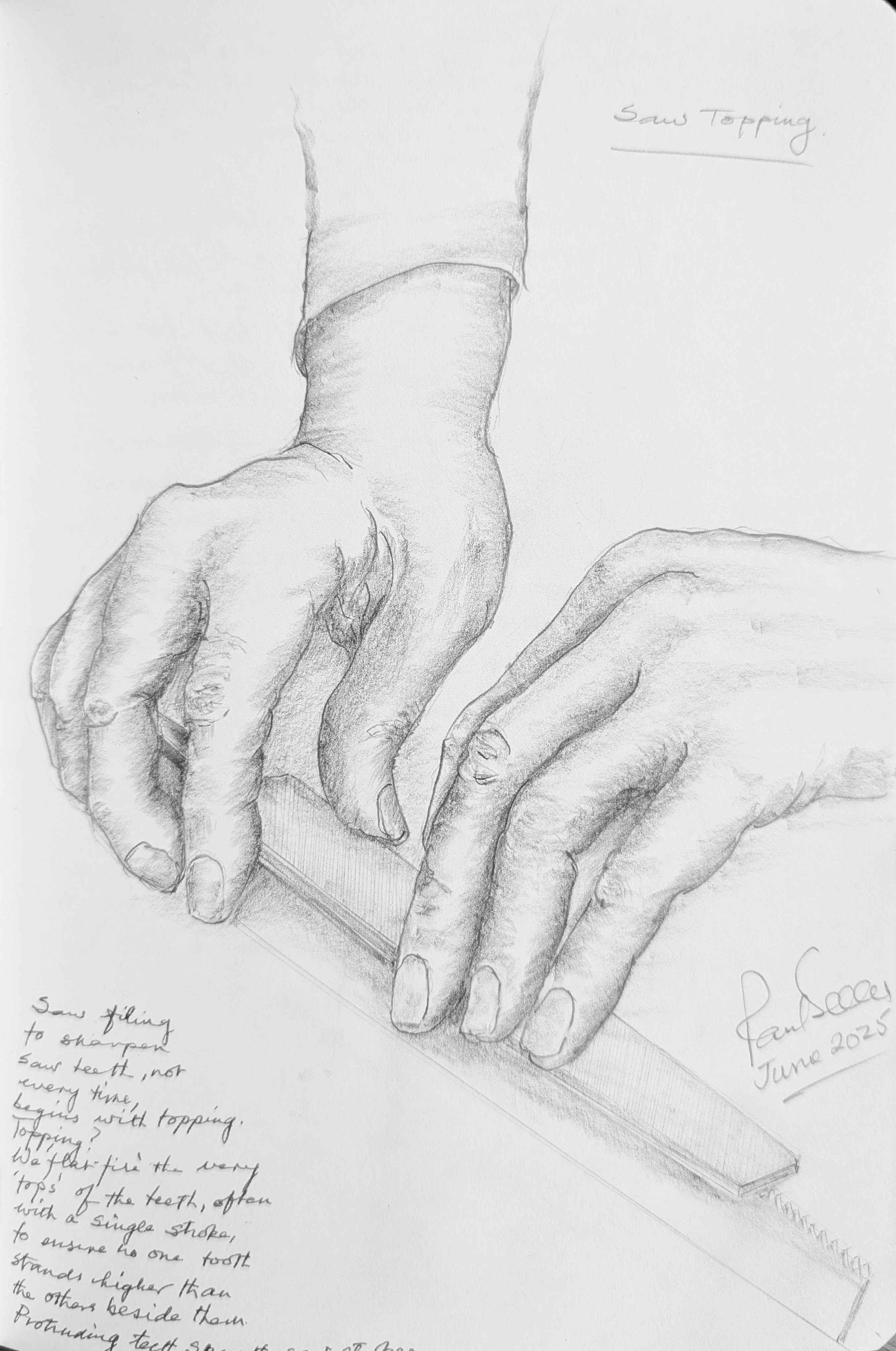

Why We Call Saw Tooth Trimming Topping––a diversion

I recall the first time I topped the saw teeth with a file. George asked me why it was called topping. After some minutes of thought, I answered. 'Because we are only touching the very tops of the high teeth.' "Correct!" George laughed.

Of course, it didn't stop there. On some saws, we don't straighten the saw tooth line, on some saws we actually create a belly to it. These would usually be larger or longer rip saws of the type we rarely use or see used these days. This belly enables the user to follow a sweeping cut and connect all of the teeth to the wood being sawn. This idea, working with the arm action using longer saws, where the arm movement worked in rip cut curving of the arm as it progressed into and through the continuous arm stroke from saw tip to saw heel.

Furthermore, the saw tips, now topped, were bright steel flats. Large or small, these bright flashes help us to see that accuracy of our previous sharpening. If the flats are even with one another, then we sharpened the saw teeth well. An uneven widths highlight our tendency to press harder on one side of the teeth than the other. If and when we have been heavier on one side of the tooth than another, then we can acknowledge our heavy-handed biases and now correct our pressure in the ensuing saw sharpening by working either side of the tooth with the file to remove the imbalance and end the last stroke with the saw tooth point dead centred on the now removed flat.

Mostly, our main concern lies with the width of the mortised piece, mostly the stile of a frame, shrinking and not with it expanding. Wood shrinks and expands according to moisture held in the atmosphere and then too in the wood. In dry climates (and houses are not usually dry climates at all) desert regions and not coastal areas, winter frozen regions and so on, the atmosphere can be completely dry. Rarely do we have our wood dried down to this level, so inevitably, shrinkage is likely. That being so, and most wood I know of bought in will likely be up in the 17% or higher, this makes shrinkage highly inevitable. In high humidity areas, the atmosphere is saturated with moisture we mostly refer to as humidity. Place dry wood that's dried down to say 10-11% in any humid place, and it might feel dry to us, it will take up moisture into its fibres according to the relative humidity (RH), which then causes the wood to expand. Once installed in a drier atmosphere, the wood shrinks. I once measured an oak dining table in the summer humidity, and it measured a quarter of an inch more than previous months because of the high humidity. The breadboard ends were 1/8" shy of the table width each side but returned to flush later.

Change of wood width happens maximally or minimally, across the grain, but hardly at all in its length. That being so, and assuming we are working with reasonably dry wood that's acclimated to the making and installation of our work and working of it, the mortised piece will expand or shrink but the tenoned part will remain the same whether the atmospheric moisture content is high or low. Now here is my point; if the tenon or the end of the haunch is dead to depth, the registering end of the tenon, butted up against the bottom of the mortise, will cause the stile to shrink away from the shoulderline resulting in a gap along the shoulderline.

Start looking for shoulderline shrinkaway as you travel and visit various places. Garden gates, window sashes and doors are great places to start. We can think that we are the better craftsman or woman for starting out with tight, intolerant precision, but this level of rigidity usually highlights flawed thinking.

It's worth understanding the importance of tight shoulderlines and that we as craftsmen take every step in our making to ensure they remain so through the decades and centuries. This critical juncture provides the ever-present wall of resistance, and when kept tight it prevents the doors and sashes from dropping on the free (unhinged) stile.

Comments ()