My Chisels...My Surprise

The lone picture on my FB drew over 1.068,172 views and a reach of 772,550 with 3794 interactions in around 48 hours. It had 15% of my regular followers and 85% non-followers. With 370 comments, I thought you would be as surprised as I was––maybe not?

Anyway, what intrigued me (as usual) was the legalism of those acting out judge and jury. I feel that I am trustworthy when it comes to my craft of furniture making. I've survived every gadget and gizmo offered as a 'better mousetrap' for over 60 as a full-time maker, but not because I reject the modern, only because much of what was offered didn't improve on what I had. I lay claim to the earlier promotion of diamond plates far beyond any other out there. My work, alongside my making for a living, took on teaching and training thousands and now millions of others and then individual mentoring here and there for new makers following in my hand-tools-mainly footsteps, knowing that most of them couldn't actually adopt my lifestyle so fully in the same way. Thankfully, I don't need to prove much of anything to anyone. I just live my life the way it's panned out. I have engineered much of it as I passed through two continents as a woodworker. A lived life speaks volumes. I may just work with wood every day, but my life has been more than that. And to be honest, I haven't met many if any professional makers that continued past their standard retirement age to continue making. Actually, I don't even know anyone, and certainly not of my age. I worked out recently that it is not so much what you retire to, but what you retire from. Tedium, boredom, adverse and harmful conditions, other people as adverse colleagues and so on can tip you over the edge and especially if you have not found your calling. Calling is everything.

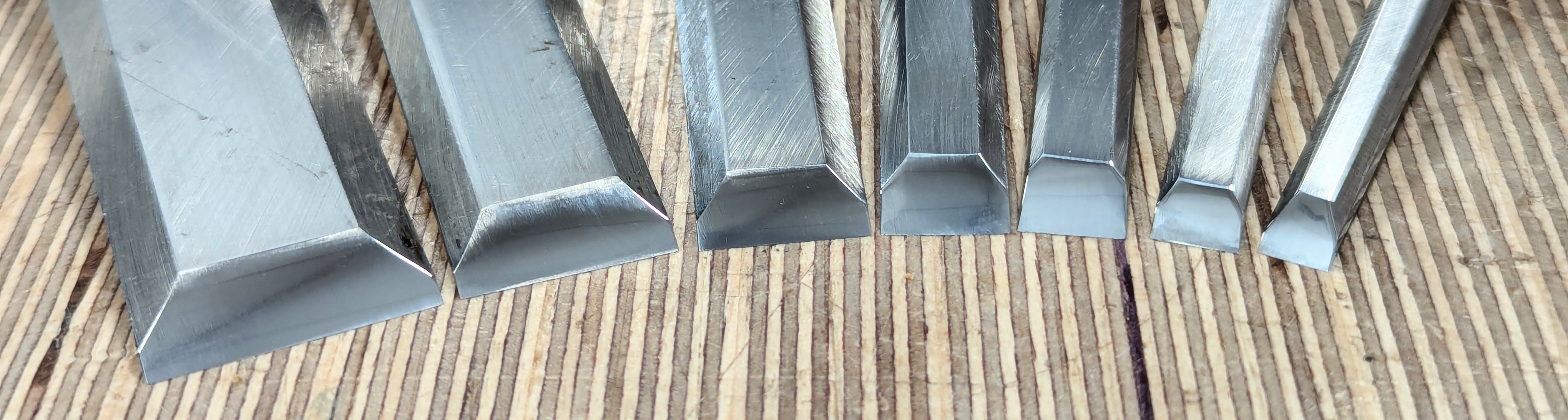

Ninety-nine percent of the commenters to the first top image gave the thumbs-up to show positive acceptance of the realness of my work tools. Somehow they knew that what they saw was more the real than the usual pretension they encountered; I don't act, posture, pretend, use hype and quick-witted repartee to draw people in. And the image was not posted to that end. I just thought people out there might like to see the real deal Paul Sellers just works with in the day to day, beyond lining them up to fit the frame, I mean, but no special photography and lighting and such. The scratch marks are really there, caused mostly by my day-to-day working. A saw tooth or two can catch, some movement of one tool over another. I place my tools on top of one another to expedite my work. I'm careful in that, yes, but I don't place my tools in neat racks or in line on the benchtop. I'm just a maker, making. I don't have an image to keep. They look about the same as my working hands, just a bit grisly, but totally, totally capable of any cut I need to make that requires a pristine surface or cut line when made––anything in woodworking you care to name.

So why did this handful of people question the cutting capabilities of my chisels? What was it about the nooks and crannies of their minds that seemed, well, so very brittle and critical. What work do they do that surpasses my standards and the standards of a hundred thousand masters past? This is how I work in my day-to-day of working? Something crept in through the recent decades of refined imagery in woodworking to present more the unreality pretension denotes as imagery. So, anyway, I just carry on in my full-on, full-time making with no posing.

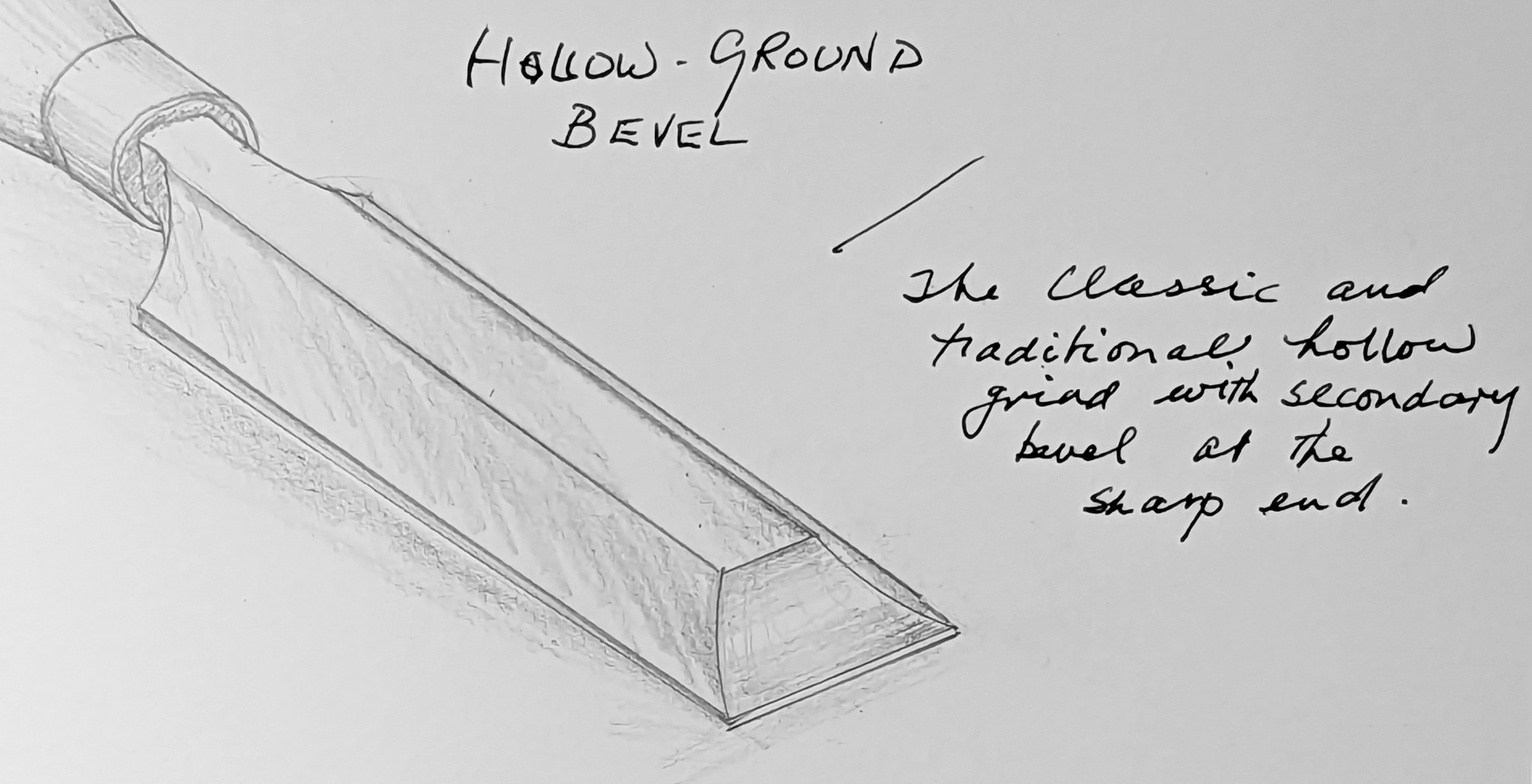

Well, somehow, so it seems, I may well have let some side down that I wasn't actually on for these few people. One, I didn't mechanically grind twin bevels of either micro or secondary bevel kind. A positive no-no, and yet, my experience in actual trials said neither one was sharper or easier than the other. They wanted a pristine primary bevel be that a flat grind or an 8-10" diameter cove in a hollow-grind but both with perfected grind marks taking the same path as the long axis of the chisel and then too across the width of every chisel followed by that second, small cutting-edge bevel, be it micro or secondary––and that's because why? Well, it just looks'nicer'.

Of course, that's not always the case of what they think. They actually tell me that it's quicker to sharpen. I don't believe that that method is at all any faster than mine. It's not. They also believe that it delivers a sharper cutting edge. Well, there again, that's not true either. It's just what they believe, but believing doesn't make it so, though they will defend it to the end. I see nothing wrong with anyone doing what they like to do, though, but what happens in the saddle of day-to-day woodworking for time-strapped woodworkers matters greatly.

The question I think we should be asking is, are we being obsessive, perhaps too obsessive about creating perfectly square-ended chisels with a pristine look to chop out a mortise? Then we might ask a more logical and probing one, is that edge strong enough to take hammer-driven blows or under many circumstances, would it just fracture? And can we really tell the difference people are saying we can between a 25º and 30º bevel when we are paring and chopping in the moment? Aside from obsessive compulsion, are we establishing something more, well, is prissy the word, if and when we want to go between chopping and paring using the same one chisel? Furthermore, if we are teachers and trainers, are we just making students and followers jump through the extra hoops to make us look more high-minded and highly refined than the ordinary woodworkers and, well, just better at woodworking than 'ordinary' people.

So, my question became this. Is it even possible that for millennia, some of the finest activists in woodworking, millions of the ancients through the ages, men and women that created the very finest woodworking for millennia and at levels we can nowhere near come close today hope to even generally match in terms of quality, versatility, etc, that somehow they just missed sharpening their cutting edges to the levels that we can now achieve with our highly refined and sophisticated micro-levels of micro-bevels? Well, of course it isn't. That's our exalted perspective of refined progress, but not the reality of where we really are. So that then begs the question, what are we saying any more? Is it that we want more to stare admiringly at the mirrored-bevels of our chisels and admire our reflection in their polishing? The reality is that we can do more tasks with a cambered bevel than we can with any other kind; try creating a scalloped edge or a cove with a micro-bevelled hollow grind. I defy you. Is it that we pare-cut mostly in our work? Well, it's more the rarity than any regularity, I'd say.

So, if you have somehow ground your hollow grind at roughly 25º from edge-tip (cutting edge) to top of bevel (heel), and then added that micro or secondary bevel of 30º, a millimetre or two wide, how strong will the now thinned steel be at the crucial point right behind the added bevel along the length of the cutting? Bearing in mind, now, that realistically we need to both chop to substantial depths, lever waste from the bottom, and then, too, do it the more in resilient woods or woods with uneven density, like the softwoods, whose hard aspects of the growth rings can be harder than many denser grained hardwoods? You know what! These kinds of questions never came up by the challengers, and yet I believe that most of us use bevel-edged chisels for the dual purpose of chopping and paring in a single chisel. Disingenuous questions come from the disingenuous, those creating straw men to protect the image they sometimes have of themselves. The faster sharpening method they espoused was never faster, and neither was saying less steel removal made it easier. By stating things that way, they suggest the alternative was harder, when in reality it was never at all difficult to begin with. They did all that they could to say one was faster, easier and sharper and needed less energy. I wonder what kind of work such people did and why, when all is said and done, they put so much energy into being very defensive and dismissive, and dare I say closed-minded?

I sometimes know, some of my responses are perhaps considered to be more abrasive than most care for them to be, but I also think that it's important to read between the lines of some. Some thought my chisels were just not sharp, but even after they had chopped 44 mortise holes in hardwoods and softwoods, or pared the same number of tenons, they were still amply sharp to continue my working with them. I doubt those that commented cared too much about such reality, but more than likely the image they projected of themselves without realising how really brittle they were.

Such things were never exemplified by the masters of woodworking I worked under and within my formative years as an apprentice. No one sat staring at a bevel a millimetre wide to admire themselves in so narrow a band of light, and yet, that's what happens in the videos our new-age gurus put out online. These things can and do take you down a track that consumes the very thing most people lack, and that is time. If you want to actually do woodworking, minor distractions surrounding support tasks, like sharpening, will sap you. I, for one, do not have that kind of time as a maker, preferring full-time, high-demand, hand-tool methods of making. Of course, those pristine refinements are quite fine when you go mostly for looks and have the spare time and inclination, if that's how you feel about it, then just go for it. Furthermore, those grinding marks inside the hollow-ground radius needed to be perfectly parallel, pristinely aligned if you will, to the long-axis of the chisel and the end of the chisels, all of them, had to be dead square. Now we need to get to the crux of the working issue. For the hollow grind of any and all cutting edges, no matter the tool, it must be ground to that hollow on an abrasive grinding wheel of some kind. That means owning a grinding machine, and most of us have one kind or another for grinding metals like steel. Once we grind a hollow bevel, and to get that to ultimately deliver a cutting edge, for it to be viable and able to retain its ability to cut, the very tip of the hollow grind must be estopped by an additional 30º, or so, bevel. Now, this is not a new thing. We've had grinding wheels for centuries and millennia. Hand-cranked, 18", sandstone wheels rotated through a bath of water to develop bevels that could then be honed on whetstones at the same angle, resulting not in two bevels but a macro-camber which is why chisels did indeed sport a cambered bevel on most vintage chisels. This difference now, of course, is the diameter of the wheels and the driving power can be had with controllable speeds via electric motors. Critics of machine ground bevels only offered that these burnt the steel, which on a regular grinder with a carborundum stone installed did do if you weren't quick to plunge in water periodically as you ground. But we have wheels that stay cool these days and don't even need quenching, along with slow-speed grinders too. The Cubic Boron Nitride (CBN) wheels comprise a surface coating of ceramic abrasive that cuts hardened steels fast without burning the steel and with no need for cooling with water or cooling fluids. It's second only to diamond in hardness but don't try grinding mild steel as with regular grinding wheels as they clog immediately and that can damage the cutting quality long term. But wheel grinding is still too slow for me, other than for grinding a damaged edge. Oh, and even though these wheels do last, they do not come cheap!

It was somewhere back in the mid-1980s that someone came up with what they called the micro-bevel. The idea was to create an initial fine bevel that with subsequent sharpening widened, and then you went back to the grindstone to reestablish the thin micro-bevel again and start the cycle over again. It was published in a magazine article and from that article, though it was nothing particularly new, many a new woodworker took the method onboard and professed it the best. But twin bevels had been the industry standard for decades before, and that came about mainly because more and more woodworkers had access to 6", inexpensive Black and Decker bench grinders, which ground a hollow grind. For woodworking, this grind necessitated strengthening at the cutting edge because it wasn't yet a viable edge on its own. This industry standard was simply called the second bevel or secondary bevel, but then, this secondary bevel was more substantive, wider and steeper at 30º and whereas the 1-2mm wide micro-bevel was indeed narrow, the earlier versions were slightly wider at about 3-4mm. Nothing new under the sun.

The fact that my 'real', daily working chisels will cut anything (and have done so for sixty years this far) I offer their cutting edges to, and with pristine cuts at that, seemed incredulous to the FB audience and yet here I am, day in and day out, cutting all of my machineless joints with these very same chisels that I stopped mid-task to photograph and post on my social media. Now I am asking myself how on earth did we get here? Surely, those in the longer-term-know, know that for centuries before, makers in every craft of woodworking produced the very finest levels of quality ever made. Dare I say this, too, not too many makers in today's age come anywhere close to the commonest woodworking of that past era. The chisels and planes did not have secondary bevels but a rather grand macro-camber. Look at the remarkable legacy they gave to us, and often straight off their cutting edges.

But I posted the realness of the moment because I wanted to counter some of the posing that's part of the image people have of themselves. That being so, it was the posers that countered my post the most–– it was something I should have expected. I think that the fact that it's a real image that counters an emerging culture of increasing snobbiness in woodworking realms that it had the impact it did. These were the ones that started out with something like, "Been woodworking 38 years..." or, "I'm a qualified carpenter..." etc, etc. I did take the time to mention that some people work with wood once a year and can say they've been a woodworker for 68 years if they are in their 80s and such. It's not the years or weeks or months you have been a woodworker that counts, but the hours you've put in. A roughish calculation for my bench time to date is 187,000 hours of super serious woodworking to earn my living by to date. And I truly say serious woodworking surrounding hand tool furniture making as well as machining but in the last decade, I have included serious videoing of my work to make certain my craft does not die because it will be preserved in the hands and hand work of serious amateur woodworkers and no way in the hands of so-called professionals.

Posting of the picture was intentional, but not to do anything more than present how my chisels really were on any given day and to tell everyone that they were the real deal of how my chisels look most of the time. All the more, we have the legalists of our craft of woodworking. This is the kind of legalism that ties a noose around the necks of others like a ligature, and that's the root word of legalism, legare. Most of us will know that any bevel between 20º and 35º will usually cut just fine? That a single bevel at any angle in between those two numbers will cut just as well and as easily as any two bevelled edge you care to make? That a skewed, out-of-square end will work fine too, but the bottom of a mortise or a groove might not be dead square but in 98% of cases, flat does not matter? That if you are slightly out by, say, five degrees, you can correct it over the next five honings without regrinding the chisel square on any mechanical grinder. It doesn't matter! Did you know that I use a grinding wheel now and again, but no more than ten times in any given year? Did you know that I likely sharpen ten edges on edge tools several times in a full-on workday at the bench, and that's without the fuss of knowing this steel alloy or that one? I have compared my chisels to harder steels and found that the harder ones extolled as being made by premium makers and premium users last no longer than my Aldi versions and that they usually don't mention that some 'premium' chisel edges edge fracture at a serious rate? Know why? Different reasons, but many of them sell edge tools either directly or indirectly through sponsorship. I haven't taken sponsorship from any maker or distributor ever.

Hang loose, everyone. Freedom comes in the real things of life and not images people have of their being more perfectionist than others! No planes laying on their sides here. Just the real woodworking that comes from the day to day, rather than imposing our wills on others.

Comments ()