Where Are We?

Is my closest friend the wood I work? Is it woodwork? Or are the tools I lift to every task my comrades in arms? I get my answers without the tiresomeness of mere opinions directly from the wood I work; feedback is important, and it comes directly and honestly from responses I get minute by minute from the fibres. It's simple. I'm guided by each fibrous twist and turn that holds tenaciously defiant at one point of my chisels edge or saw tooth and simply yielding at another. Today, my day unfolds once more in my making.

It's a Monday, and I am glad to be here. I take a wood most have never known nor used. Its bulk is large, and any reduction in this kind of wood defies a maul and splitting wedge––it's not like oak, splitting dead straight and to size just by the looking at it. I bought it semi-green five years ago, when then it was five years old since the miller dropped the tree, slabbed its bulk into sections and sold his efforts as beams and boards in an auction.

Air dried outside since then, the wood was still pretty near saturated lying outdoors beneath its ugly blue tarp. Poor storage always results in unintentional spalting, but spalting can be intentional too. In beech, spalting is always stunning and to the unaware, as the discoverer peeling away the leaf and mould-covered tarp, the reward is very special.

I challenge myself in my making of things wood. It's not the design or its complexity. My expectations are fairly predictable these days, so I take that as it comes because the designs are all my work and therefore my choice. No, it's more the bad habit I have of my setting myself times for tasks, knowing it's self-imposed and not the demand of others. But time constraints are goals that disallow procrastination on the one hand, but that essentially help me achieve and deliver within what I consider to be a planned time frame. Some woodworkers, the ones who've retired mostly, I think, might avoid this kind of limiting because, well, they had it all their working lives. It's the illusion of a retirement somehow giving added and unrealistic freedoms that I mainly avoid in the shop. I haven't clocked in and out of work in 50 years. I set my own hours and generally settle for shorter hours now that I am 75. Even so, I still work around 10 hours in a given day. At my peak of making, teaching and training, my days ran into 16 hours from start to stop but with meal times encompassing family and friends.

I think it's all too easy for me to forget that people more likely retire from something rather than to something. I'm retired into something; my craft is something I chose when I was 15 years old. That being so, I see no need to stop working at what I loved in my earlier days, loved all the way through the decades and still love just as much today.

I believe that without goals, we usually achieve far lass than we could and should and then too, without goals, we allow too many unnecessary distractions here and there along the day. A few years ago, I watched younger makers come into work between nine and ten, log into their computers and then dip in and out of actual making throughout the day. I couldn't relate to anything they were doing, but production rate was probably a quarter of the work my mentors made in their day. My time frame for a drawer corner with a triple dovetail, common or half-lap, is under an hour: perhaps forty minutes or so; no more. We develop methods and techniques in our decades of making that make the methods and techniques ours. This owning of processes gives us a speed most will never know now. But then, that is not necessarily what makers in their garage are looking for anyway. There are the small nuances in the twist of a chisel, the flex of a saw plate and the lifting of loose and loosened fibres that evacuate waste quickly as we move seamlessly through the steps of our work. When we press the dovetail with our thumbs, there is just enough friction uniting with fibre compressibility either side to ensure a joining of pin and dovetail within the walls as the interlocking fingers of two hands. Glued or not, they'll stay joined for a century or two when done right. It's the same with our tenon's fit to a mortise hole, too.

Usually, no matter the size, I allow myself about eight minutes for a mortise. I realise that that might sound silly, but it almost always works out. It's the same with sharpening saws; four minutes for a saw, no matter the size, is almost always what it takes me. A twelve-inch, twenty - point saw has 220 teeth and a twenty-two inch, ten point saw has the same. A saw shouldn't take more than a single pass through each gullet with a saw file to effectively delivery the crisp pinnacle for a shearing cut, if it does, the owner neglected the saw by failing to maintain the sharpness levels of the teeth or a nail or stone got in the way. Why do I sharpen quickly? Mostly, it's the work ethic and the movement taking me smoothly through my work. Sharpening of every type needs to be as integrated a part of the making process as possible. Though it is a different task, I don't see it as so distinctly separate any more but simply an extension and complimentary part of the making continuum.

Also, it's not the length or width of a mortise that determines the time it takes to chop out, I find. No, a 6mm (1/4") or 10mm (3/8") takes about the same, but the depth makes the task longer. In furniture, it's less usual for the work to need deeper mortises than 40mm (1 1/2") (unless it's a through-mortise) most mortises are sufficient between 25mm (1") and 30mm (1 1/4"). Generally speaking, that is.

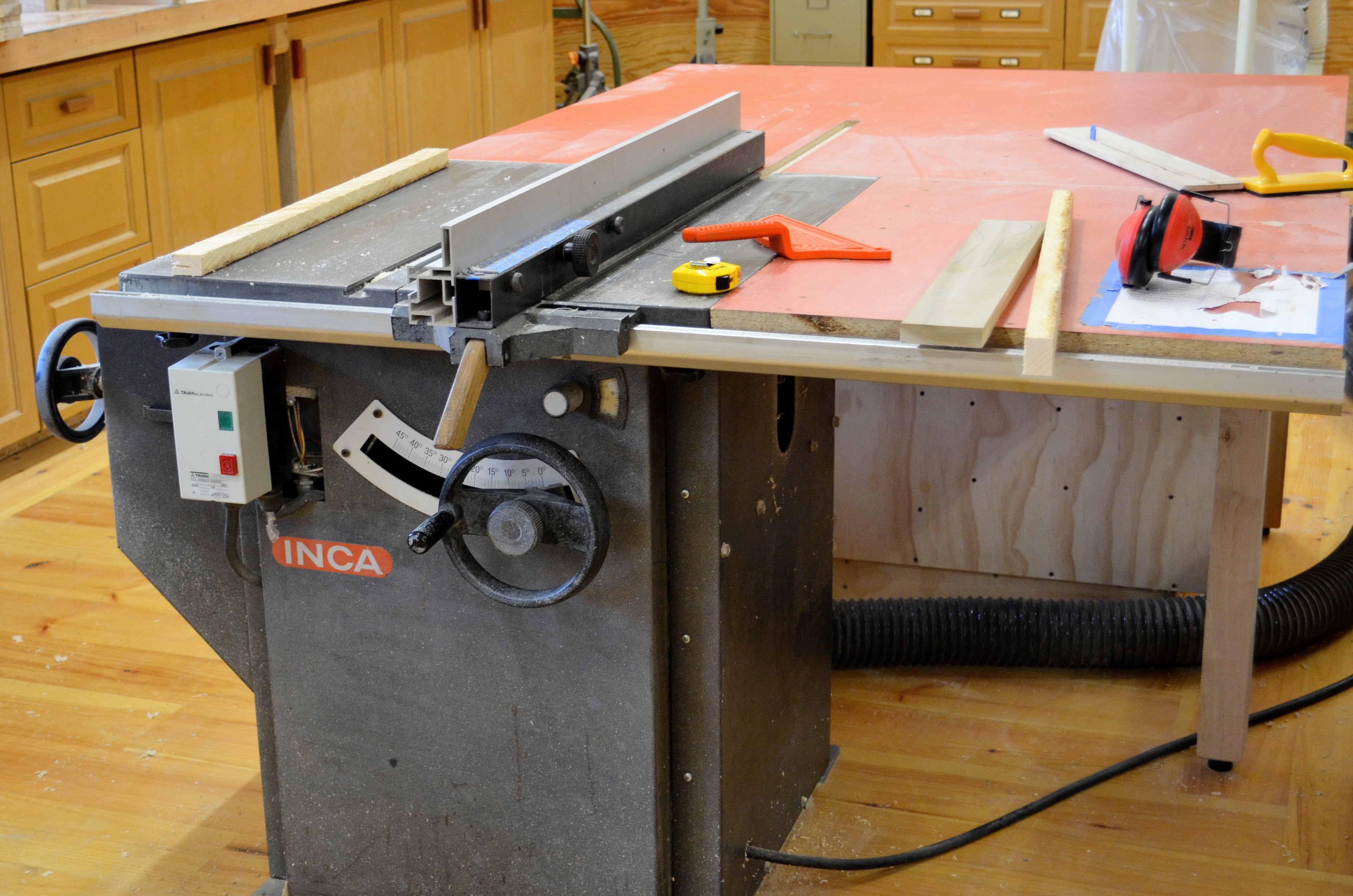

My one machine, my bandsaw, has been sufficient since I stopped teaching hands-on workshops; I no longer need a thousand pieces of wood to exact sizes for a two-week class. The space-saving with a relatively dustless atmosphere is a lifesaver. Shrugging off that dependency was one of the most freeing things I ever did. People can swear by their tablesaw, say it's as non-negotiable as a microwave is in the kitchen for softening butter, but important for me is the reality that the bulk of my audience could never own such machines and even if they could, from choice they are looking for the demands hand work demands of them. It's taken a few decades of delivery from me for me to persuade woodworkers to adopt hand tools for more major work like proper joinery, wood shaping and much more. Believing in them, I made it my goal to create videos that they could see the action and what it actually takes to establish a wide range of skills. Today, I get texts, comments and emails telling me that they have pretty much relegated their so-called power-tool equipment to the back corner of their garage and work mainly with hand tools. I recall the days when I was the only YouTuber dismantling a plane to restore it. I'm sure you'll find a thousand today. The adoption of developing skills for high-demand making with hand tools wherever and whenever possible is as important now as it was millennia ago, even if it is now for a different need.

The space hogging, the outlay in money, the noise for neighbours and then the dust extraction is not in any way practical for the high-rise and tight-spaced maker. That would be more a privilege. But then that begs the question, what's the difference between a tablesaw and a bandsaw? Well, I have found that the bandsaw footprint is considerably smaller, no more than two-foot by two-foot, really, and so too the methods used to work it. A few years ago, I even bought a pocket-sized bandsaw to see what it would do. It surprised me with its loading of really decent bearings and adjusters that worked like it's bigger brothers. A 12" version with a sharp blade readily resawed 6" thick oak and was light enough even to bear-hug-lift and move around or place in a corner or even outside for an hour or two. I will park this here, as there is much more against owning and using a shop-full of machines, especially if space is precious. Believe me, a bandsaw, once mastered and set up well, will save masses of deep sawing through the thick wood that a tablesaw will never do, but more than that, it can take on many a task type that give you markedly improved health levels too!

Trying to help some woodworkers adjust their way of thinking is challenging and frustratingly difficult; my answers move between caring and curt, but that's because I always try to read between the lines of comments. Some show an assumption that everyone should be in mass-making mode all the time and do whatever it takes to just get the job done and get it done yesterday, that everyone can and should own a full machine shop, and that there is little value to working using hand tools any more. The reality is that there is more value to my style of hand tool woodworking than they would ever know and therefore understand. There is an assumption on their part that a machinist will know as much if not more than a hand toolist, but, mostly, I haven't found that to be true at all. My work has always been my daily workout, both mentally and physically, but it's much more than that. The engagement with the wood is a hundred times more high-demand than with a machine. I don't need saving from drudgery and tedium; handwork is my preference, and so too the choice now of hundreds of thousands discovering the art for themselves. We are not looking for the easier path, but the high-demand hand tools give us to achieve our goals by. The two bedfellows, drudgery and tedium, don't exist for me and if they did, they would help to build my character, I am sure. That said, I understand disabilities many woodworkers must work with and machines can be enabling to arthritic hands and the myriad other disabling elements to life. I think tough that it is important to see that not everyone can or wants to machine wood, and for more good reasons than bad ones.

My way of working is a choice and through the decades of making and people seeing me make, I learned that it wasn't isolated just to me, others wanted it too. Coming to the conclusion that my US classes and hands-on workshops only touched the tip of the iceberg of woodworking, I started thinking less defensively and became proactive in engaging with those standing around my bench trying to understand my methods. I wanted to help them reconsider their thinking and the to discover the hidden fruits of true crafting. Some were still in the beginner phase of woodworking, while others had machined wood for a long time. The influence from magazines and woodworking shows leaned in at about 95% machine work, As a result, most of the US woodworkers I came across over three decades saw machining as a first and often only option. It was at shows that the tip of the iceberg began to show in small pockets, cluster groups that began crowding around my demo area but then kept expanding as the crowds grew. When they spilled over into the aisles at the mere sound of a handsaw cutting a dovetail, my heart went out to them. Could I give what I had to them? Of course, I could!

The surrounding booths were all in for the hard sell. Hand tools or machines, these were all selling venues relying on sales for business. And the contrast between these enterprises and mine was obviated by the peace and simplicity of my woodworking. Hos is it possible to cut a twin-dovetailed corner in two minutes and have a perfect fit? The fishing line was cast, and the hook set purely by contrast. Once I started demonstrating hand tools, I didn't stop for 45 minutes, going from joinery to inlaid and moulded picture frames, and not one person every left their seats the whole time. By way of contrast, no one seemed to want to watch someone with goggles and a dust mask on using a power router to mould a stick of pine. My using a moulding plane to do the same thing, on the other hand, opened their eyes to past methods that worked amazingly well. Making some assumptions assumes that we all have the same wealth, space, access to less expensive machines and more. Having lived half my work life outside of Britain and then returning, the fact is that machines are way less accessible to the majority for various reasons. Those that counter my way of work often comment with quite inappropriate statements, thinking and then judging others to be working in less advanced and more archaic ways of working wood with no good reason.

This last year or two I feel I've turned a corner despite the increased competition for what's really no more than what I'd call 'the attention deficit' of this and the last half of the last century. Mostly it's to do with the amount of time most people can allocate to actually spend on what pops up on the screen. Remember, these screens barely existed two decades ago and YT is only that old. Everyone knows that they are being bombarded with information, and how much more those of my generation who have a longer period to compare it to. In split seconds, something pushes them to quickly scroll on and at the same time make decisions as to what they find interest in. This takes a toll on the amount of attention anyone can give to just about anything.

I haven't changed, but video making has. Authenticity stands out and will always stand the test of time. In my early days of trying to help hundreds and then thousands of woodworkers to get started with hand tools, I had not realised that being real has such a powerful dynamism all of its own. I didn't need a series of machines set up like a mini factory to process components. Working from a simple home-made workbench made without a bench begged many questions from a questioning audience. One year, I travelled between half a dozen shows in different US states, lugging the wood for making a workbench in each show. By the sixth show we had the giveaway bench and passed it on to a winner. That was so complementary to what I do, and I was glad to do it. What I do today has barely changed in the 60 years since I began. This is likely not possible for most people in their work. What would I change if I could? I'd spend more time encouraging woodworking parents to explore hand tool woodworking in the only way I know that would bring their children into the garage workshop. Start them young, make it fascinating, include nature wherever possible and spend time with your children. Woodworking is not an adult's only craft, but a family affair that builds and maintains bridges and links. If we don't involve children in our woodworking, we may well see it start to disappear. It's my belief that the future of hand tool woodworking cannot rely on those working to derive their living from it as professionals, so very few of them have any experience with hand tools and probably far less than most. My granddaughter and I spent four and a half hours in the woods, by the lake, in the workshop and sketching. The first thing she asked me when I picked her up? "Granddad, can we do some woodworking?"

Comments ()