Choices

I remember my introduction to machining wood. I was aged sixteen, when every task seemed to become a machining moment in small and long bites of soul-destroying boredom that just kept building. Oh, I'm not talking about the hobbyist woodworker who sets up a mini-conveyor belt system of minor operations going from crosscuts to ripcuts to jointing and then thickness planing to downsize stock in quick succession. Try crosscutting a thousand pieces over an eight-hour day and then the rest of the week machining it all down ready for the spindle moulder to mould twin rebates, and moulds to stiles, window frames and sills. It was nothing to spend three hours crosscutting material for other processes, be that moulding on a spindle moulder or tenoning on a tenoner that tenoned ten sticks at once, replete with an ogee on two corners one side and stepped rabbets the other. The chisel mortiser, the chain mortiser, and the massive bandsaw were my first machines, from there the door opened for others to fill my workday year-on-year and I graduated to become a junior machinist. The difference between a junior and a fully recognised machinist? Pay. I got £5 a week and he got £20. We both did the same work, but he could set up the power heads to the machines.

I met an interesting student in one of my classes some years ago, an ordinary man with a working background, someone you might pass on a street or sit near on a bus. Once.in a quiet time in class, he told me about youth growth. We were talking about young men in their mid-teens. He said, "Try to imagine that boys of the mid-teen age have yet to grow a thumb to complement each hand in their function. Its growth could be but a few weeks away, or perhaps months or even up to five or six years yet to be. It'll come when it's ready and has nothing to do with him. When it does, it's that that will enable him to grasp what he needs in life, but until then, he won't understand some things, be able to use some things, nor able to do some things. That's because, well, his thumb's missing. So it is with the brain of a young man. The synapses as yet are unformed. They are not even there, let alone functioning." Of course, synapses are not thumbs they are neurons, but the correlation is real. Strap your thumbs to your palm for a day and see how well you feel about it.

Some of you are surprised when in times past I have said anyone under the age of 20 or so should not be using any kind of woodworking machine or other power equipment in the wood shop, how many proud and prideful dads pushed back on me, jumping in to say something like, "Well, my kids have been using a chainsaw since they were this or that blah, blah age . . ." No matter. I don't really care too much about what they did or did not allow. The ones whose kids lost fingers or an eye never post a comment. I have known grown men in their forties and on up who used power equipment all their lives get their teeth smashed or swipe off a finger or four above the knuckle on a machine. It's easy to do and easily done. Just a second or two. And the now famous SawStop doesn't stop several other machine accidents from happening. Someone asked me in the middle of the demonstration on hand tools, "Okay... What's the difference between using a handsaw and a power saw?" I waited a few seconds, knowing the question was loaded, it was a so-called 'power tool' woodworking show, and I replied, "In my experience, when you slip with a handsaw, you always stop before you hit the bone." We moved on amidst the laughter.

Inevitably, before I was a few weeks past my sixteenth birthday, I had learned all I would ever need to know about machine work. Mostly that was about machine safety coming through near misses. In the maturing year of seventeen, I learned about sharpening and setting circular saw blades 20" in diameter, honing mortiser bits and such. Back then, we didn't have tungsten tipped teeth on our saws. Sharpening a circular saw that size took only a few minutes with a flat file followed by a round one to deepen the gullets as you went. Planer blades were the same...steel only. From chain mortisers to chisel mortisers, we hand filed everything and it was fine. Of course, progress came along and gave us tungsten tipped everything, and we had to send them out each week and have spares to exchange so we never ran out of a sharp-edged blade or cutter. Nowadays, it's cheaper to change the blades out and toss them–– under the banner of 'Progress and time's money!'

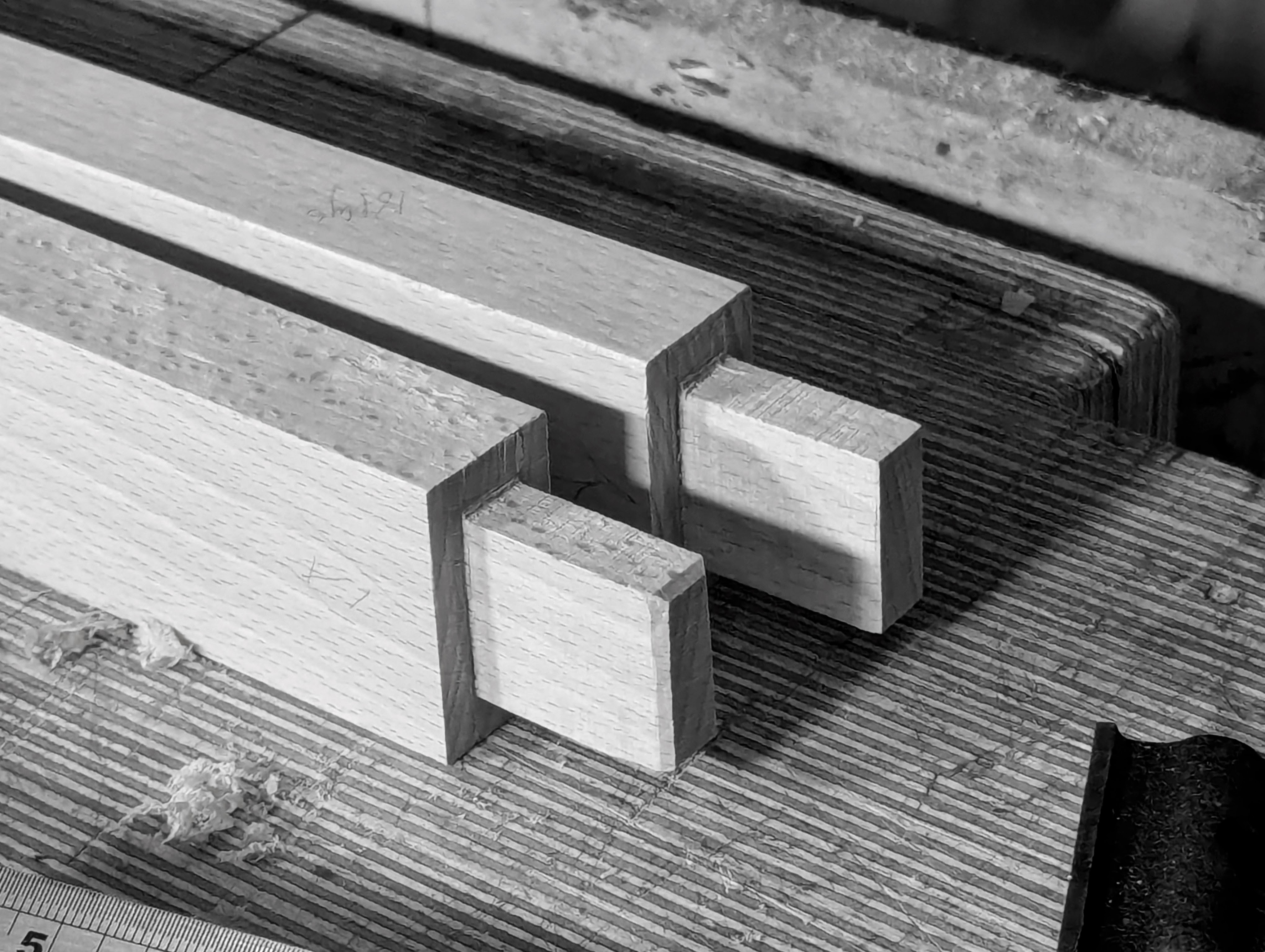

I just watched one of my recent videos. Reviewed it to make sure there were no glaring mistakes that someone might follow and create a problem for themselves. What struck me the most is that you would think that cutting a mortise and tenon would be the same every time, but I often do things differently and add hidden gems that are never filtered or retaken but just flow out from my in-house brain archives. The diverse working of wood by hand methods solely with hand tools gives me many, many choices: options, yes, but all of them predicated on the wood I am working and the knowledge I have of wood and tools. For machining wood, this knowledge and ability is unneeded. The cuts made are out of the machinists hands. The removed wood gets pulverised by a thousand cuts per linear inch coming from the power head. There's no more to be said or done.

Watching that video, following gauge lines and knifewalls, fine pencil marks and thin lines, I pare-cut, split-cut, saw-cut and chop-cut the tenons to enhance my offering to an audience set on learning from what I do, yes, but also, moreso, it's more because that's what I do in my normal working. Variety of work types spices up my life. And guess what! I did it throughout my life making my living too, so to others in self-employed working, where money was the main and maybe only objective, I chose to make the work itself interesting beyond income because my work didn't revolve around money alone, the way I wanted to work became my lifestyle.

There is more to changing tactics than meets the eye, and it's this that most woodworkers fail to grasp. In a business world, the way of getting things done is whatever goes the fastest and delivers the best quality finished product at the best or most appropriate cost. Usually, working wood as we do, in the way we do, makes it woodworking rather than machine making. The outcome is not only the finished product, but more or most importantly about the whole process from beginning to end in all of its various stepped and staged processes we actually choose for ourselves to use. By this, we can all the further improve much more of our making life in every sense of our working the creative spheres of making. Once a machine is set up, identical replication results in repeat cuts according to the stops and starts on the fence or the flip-over stop along the sliding fence or table. Machinist may refer to a cut as a single cut, but, of course, they make a thousand cuts to our one. Pulling a lever or pushing the wood results in teeth and cutters stacked behind each other to make that cut. The cuts we make slice and pare, shave and sever in lowering pass taken down by a thousandth of an inch until we hit the knifewalls that keep the exposed corners crisp. We see by this that every single cut we make is in the control of our whole upper body engagement. Every single element of our whole body MUST engage in the work. Nothing, not one element, can be left out. Such hid demand becomes critical to our being and after a few months and years, it's intrinsic, as it should be, to our life making. We depend on it in the same way we rely on air for our breathing. This common work has become the uncommon and the extraordinary to most people machining wood because mostly they no longer do such things. In the machine processes using mass-making methods, there is only very minimal reliance on the steady handedness, and minute by minute redirecting to optimise the output of a cut. In machining wood, fences and presets align everything for mono-directional conversion, all of the energy is about ensuring nothing interrupts the passage into and through the cutterheads and blades. Our work goes far beyond the mere linear push and pull of it to flex and twist and distort our bodies to maximise the efficiency and accuracy of every single cut.

My choosing to work the way I do was enabled by my training, yes, but more than that, it was my decision to self train all the further once the basics were taught. Some people do undermine my positive encouragement by saying things like, "Yeah, that and sixty years." It takes a matter of a few weeks to master most of the skills I have. The hard part in a time-strapped world is stitching the days together for a concentrated period of self training. But if you dispel the microwave mentality to learning, and pace yourself for a year of a few days per week, you should be well able to do everything I can do.

Comments ()