Things New

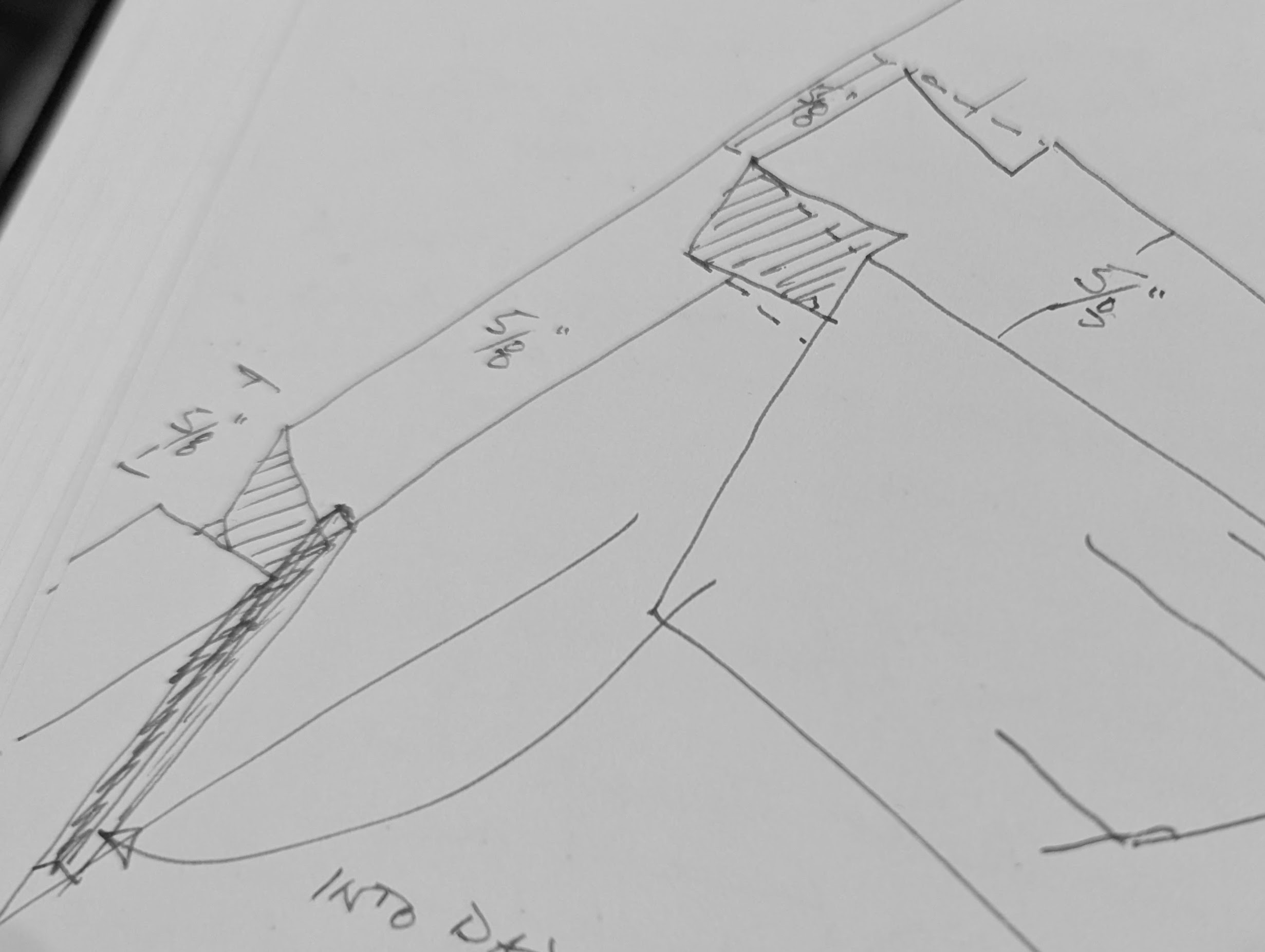

Something stirs deeply in new beginnings. The gestation of an inspired possibility in the ordinary of life prompts us to think of things beyond our capacity for a thought is nothing more than the expansion of a small cell, a pulse of oxygen, of blood and our brain reshaping, refolding itself with valleys between ridges, sulci and gyri, to move every element of our being and the extensions of our bodies to tap keys, lift pencils, wipe a white page in a notebook to rough out the thoughts in grey lines, and then we feel the exhilaration of possibility in steps. How is it possible that through this we move the future, tell it to extend, to expand its boundaries, and in the moving of the material, the expanding of all space, we stand to make, and we make the things that make change happen?

Kick-starting anything new means changing the familiar and comfortable to unsettle and disrupt what we've become so thoroughly adjusted and conformed to. Kick-starting a new idea affects every element of our life, necessitates time changes, patterns we've created to work on something else elsewhere before to work again but differently. The people we work with, family, friends and all others are all affected in some measure. Managing our expectations and the expectations others have is part of the creative process. Just as we usually do not altogether like change, neither do those around us. But creativity is mostly about transforming the ordinary to create something that has an extraordinariness about it. The distinctive small thing is often what makes the sizeable and noticeable difference. I closed a thought that began eight weeks before with the delivery of a new, hitherto unseen piece to my home.

Past or present, the year's contrary news affects all of by varying degrees––of course it does. Hard to imagine such escalating barbarisms created by the self-indulgent and self-righteous, and then genuine causes too. Catastrophes lead to great destruction while we creatives intent to make and build, better life on each continent by taking our thoughts captive and rebuild in the face of the destructives. We're disappointed, but never disheartened. Each project, celebrates our creativity, yes, but more than that, it expresses our hope so much that we just keep making and making despite the intent of others to destroy.

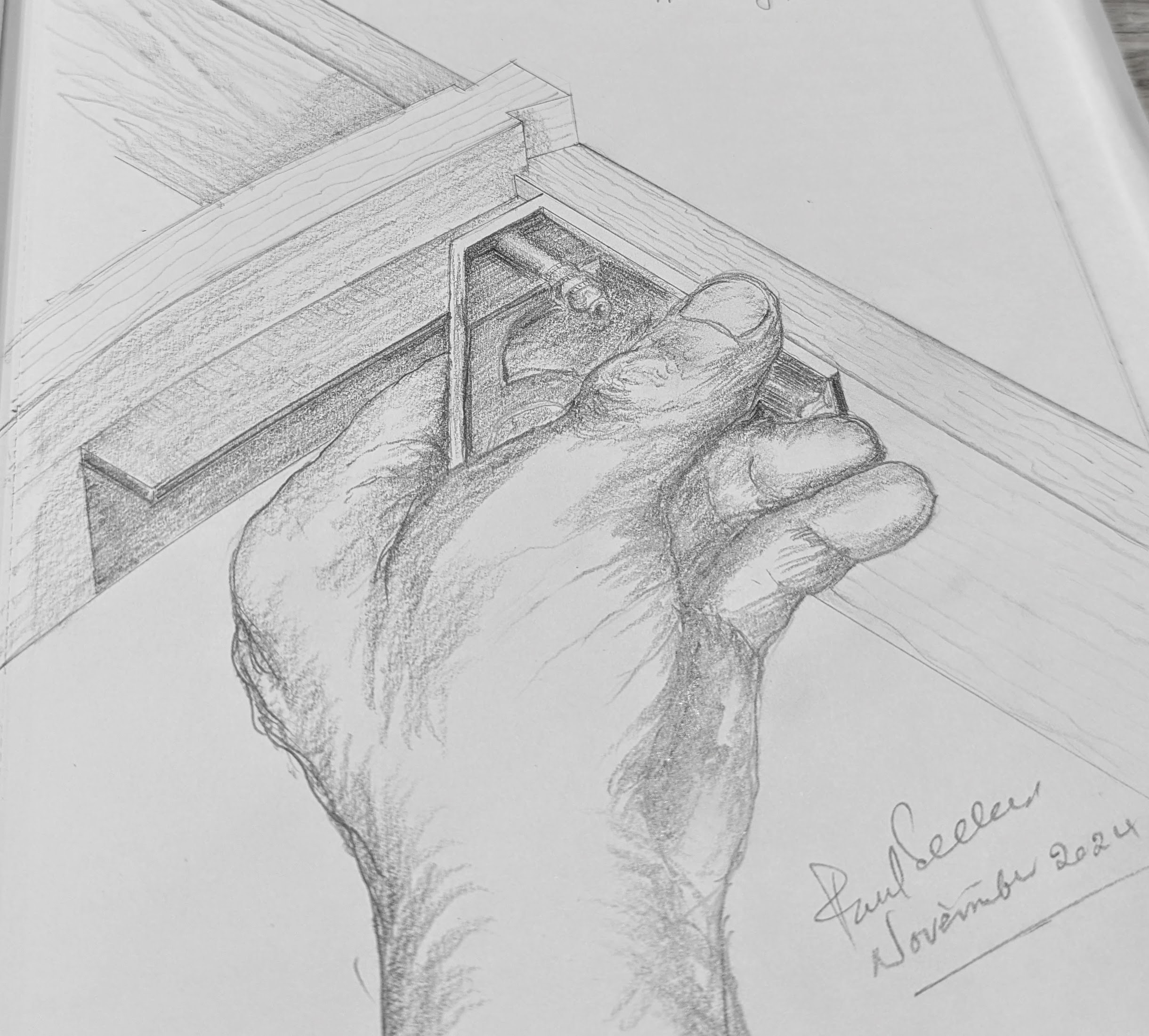

Many say to me that machining wood is the progressive way forward, and that using hand tools to make is far too slow and arduous. Of course, that's not altogether true but there are minor truths in there I might occasionally agree with. Slowing down the tasks of woodworking is something we many of us aim for. Those who decide against handwork deny themselves what we hand tool woodworkers want. We want the slowed-down version of woodworking, we ask for the challenges and love high levels of self-demand in the same way sportspeople do when they run a few miles or sprint a hundred metres in a few seconds. Imagine the two world athletes, Florence Griffith Joyner, who retains the world women's record with a time of 10.49 seconds in 1988 and the men’s record held by Usain Bolt, with his 2009 time of 9.58 seconds if they had chosen a machine method to beat those records.

What hand tool making gives us is a realness we cannot achieve any other way. Using my hand tools in the last few weeks of 2024 was remarkable. A hundred pieces of wood with every facet planed to perfection with a #4 bench plane puts all of the work squarely in my own hands. The brain cell I spoke of earlier was totally receptive, and it equipped me for all of the tasks it took to make the dressing table: nothing was held from me. My own feelings are that we should never despise the small things, no matter the smallness of them, the distance they may seem from us, such like that. My sixty years of daily making at times left me midstream with a sense of impossibility––now, looking back, I can hardly think of a single one that didn't fully materialise from such impossibilities by plane and saw strokes. Such is the reality that, in its day, this, being the cutting-edge technology of its day, never became obsolete to those of us outside of the mass-making, mass-manufacturing world. To us, these hand tools are of equal value and equal importance to our lives as it was to those who invented them hundreds of years ago.

Making my latest cabinet, those opening days with rough-sawn wood leaning against my back wall, mirrored my apprenticeship in that they seem so very small looking back. Thinking about it now, those small things, the thirty odd hand tools, the sharpening of edges, the layout I mastered, such like that, were and still are small things. Let me tell you this. These small things disciplined me, exercised me, kept me healthy and strong and supported me financially every day for 60 exceptionally wholesome years. Looking back, every aspect of it was a very small thing. And more. The invention of every major aspect of any success or failure began with an expanding cell in a man's brain and a woman's brain or a child's brain in the end. That's because the bigness of the whole is always about laying down step by step ideas just ahead of each stride. Really, life's all about laying down small steps. This is how we master our foundational skills of true craft. A hundred thousand of you out there may consider your handful of tools to be miniscule and the workbench you made from construction wood to be less than you might have wanted or need. Believe me, I have made hundreds of pieces with less than thirty hand tools and no machine use at all. If I can do it and still do it aged 75, so can you.

My garage space, the one you see me in when you watch my videos, is the real space I work in to make all of the hundreds or so woodworking and furniture pieces you've seen me make in real footage. The biggest workshop I ever worked in was 40 feet by 80 feet. It's the one I met my students in, made all of my furniture in, and then too the one I met President Bush and Laura Bush in after I designed my White House pieces. Would I trade my compact garage space for a forty by eighty foot workshop? Not on your life! And what you have seen me make in through the last decade and half is good enough for you and anyone else too, providing they enjoy high self-demand woodworking using real tools, real wood and real skills.

My early days of woodworking USA were indeed small, tiny, miniscule in output and even less input back to me from elsewhere. Thinking back on what I saw as opposition, those who seemed more, well, aggressive towards me when they saw me working with an old dovetail saw, I realise it was really more their bemusement. They weren't sure how to react to my presence there. Incongruity can do that. Not only did they not understand what was happening by my presence at such shows, the reality was that they quite simply couldn't and neither could they altogether understand me or what I was doing. Their concept of woodworking was machining wood, not one and the same thing as hand tool woodwork, and not even linked as such when you take my way and put it into their context of plugged-in woodworking. They'd been programmed to the precepts that they found their kind of value in, things evaluated according to speed, efficiency, economics. These were the ones with the superior knowledge. I can even say that they, by varying degrees, and as professionals, not all of them, found themselves despising more my endeavour to teach such archaic ways than me myself.

Here, you had what appeared to be an English woodworker, an unknown newby-kid on the block, yes, but more than that, a fish out of water demonstrating hand tool woodworking at shows dedicated wholly to machines. These shows showcased fifty machine types alongside machine-only methods and machine support equipment, dominant distributors like Woodcraft, Woodcraft Supplies, Rockler Inc and such. There I am settled or nestled in a 10-foot square booth, miniscule compared to the 70-foot by 70-foot set-ups on every side sporting massive banners spouting every big name you care to name. Think DeWalt, Milwaukie, Bosch, Delta and a hundred others and little ol' Paul Sellers showing how common hand tools really worked and working from a five-foot, homemade workbench. What was I selling? Well, most of the time in most of the shows, a total nothing. In those days, I, me, sold a great big nothing: I simply demonstrated my craft. There was no woodworking school and no hand-made furniture selling. How different things are for me today. In that day, I simply wanted to address the loss of skilled woodworking, real woodworking, what I later identified more accurately as lifestyle woodworking

This week was the new beginning week of 2025. It's an important year for me because many things have yet to be unlocked and last year's planning will hopefully come to pass.

Comments ()