Results Sawing and Plane Work

I'm convinced that sawing and planing is much more than separating a single piece of wood into two or more pieces, and that planing is more than levelling and smoothing. I know that a lot of people woodworking have the more pragmatic dogma that surely the end result is the same, except that the machines make light work of the tasks and deliver greater levels of accuracy in the third component of quick time. Ripping through 2-3" of oak is no easy task, is not much fun, and I generally don't do it. Make it 6-8" and it's especially prohibitive. That's why I own a 16" bandsaw that will cut up to 11" and a little more if I need that. So if that's the case, Paul, why not just go the extra mile and install the chop saw, radial arm saw, planer, jointer and tablesaw? Surely, that is maximised pragmaticism. Well, if that is your reasoning, I think you should most likely just move over and move on. I've lived with such reasoning from others most of my life. One brilliantly stunning reason is that if you have never mastered hand tools, then it's more than likely that you must leave your kids outside the workshop door until they are 18 years old and even 21. There is a good chance that, like most of your cohorts, you can't do woodworking by hand, and therefore you cannot be inclusive of the young and moldable. That would be enough reason for me to master hand tools. I think most of you can guess the rest. Woodworking is not nor should it ever be an adults-only craft except in industry. For us, life is very different. So I will park that there. My bandsaw takes the smallest footprint of all the major woodworking machines, together with the smallest of dust extractors to partner it.

The art of sawing is a graceful practice once you get beyond ignorance to realise a sharp saw needs no bludgeoning your way through the wood with a less than adequate saw. Art in action comes only from sharp saws and refined technique, plus some. I rip, crosscut and plane my wood through and through by hand every day of the year and I always have done so. I have come up with my own solutions to counter what's considered by most to be highly problematic, and also to speed up processes. For instance, I might use five or six hand planes in the process of flattening a board to a comparable level you might get using a machine to do it, but the time it takes is longer. Here is a difference, though. I just planed up an eight-inch wide oak board using four of the planes. It took me ten to fifteen minutes of pumping iron through the concentrated energies that it takes to thoroughly plane with accuracy, but though those minutes made me a little breathless, the results were the exact same as you get from running but with results you can see and feel and enjoy. And more than that, that remain. For me to get that level of cardio in a gym or such, within two of those starting minutes, I would, I have to say it because I never say it about anything else, be so thoroughly bored I would say no way. Now, as to fitness, I doubt that many would criticise me too much. In six weeks I will be 75. My BMI 24. I'm grateful for that, but I do understand the essentiality of exercising for exercise’ sake.

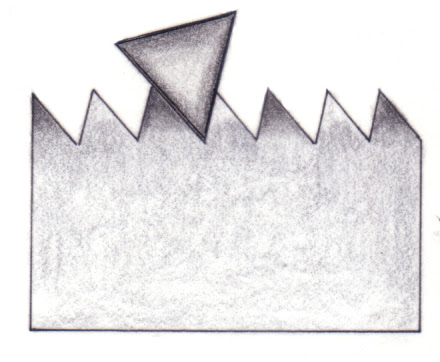

Sawing and planing is much more than forward thrusts and reverse pulls. In the start-cuts there is no rhythm, but after the first half dozen opening strokes the rhythm sets in and when ten strokes are passed, the unity between work and wood comes together stroke on stroke. With sawing, it's the opening half a dozen cuts that set the course for a true-to-the-line passage. With a heavy set, a saw path can be changed on a whim and corrections can be made almost all the way through, but the issue then becomes the quality of cut. Tight tolerances on the saws set gives the clean line we strive for in the walls either side. Cutting tenons and dovetails with smaller saws with shorter tooth spacing and smaller teeth makes the saw less aggressive and as most sawing with this saw type is crosscutting we tend to cater to a rip cut pattern on the tooth rather than the more pernickety crosscut pattern. Larger rip saws can be heavy set because of the grain and the direction of sawing. It takes much more energy to saw with a heavy set saw.

I can feel the tension in my body as I saw. Some of it is necessary and some not. I ease on the one and encourage the other. Being like a bull in most sawing is rarely ever necessary. When we get down to fine sawing of dovetails and other joints, it's important to feel the wood through the saw and determine grain resistance as we progress, but it's also important they recognise feedback from the saw plate as the saw passes through the fibres. By this, we engage the passage with sensitivity to the fibres in the walls either side of the cuts as they deepen their way to a cut's concluding separation. This kind of exercise develops unique elements to the muscle without creating harmful and the excess of unneeded muscle mass. We're feeling for the finest resistance in the end-grain fibres we are cutting stroke by stroke and tipping the hand in slight and partial rotation to align the verticality of the saw with what we cannot see or hear. We must feel for two or more pressures. The first is the discharge of pure energy you effect in the cut, but the second, equally important sensing is the almost indiscernible feel for alignment in both the reverse pulling cut as you prepare for a return stroke and then the forward cuts that follow. Of course, I am talking about Western saws. It will be the reverse for Asian saws cutting on the pull stroke, which also must be sensitively aligned.

No one talks of sensitive alignment and the exercise it takes for both power stroke work and then the awakening of gut-sensing that is intrinsic to keener work. This does not happen overnight. No matter how sensitive you are, until you know what you are looking for, or should `i better say feeling for, you won't be aware of the added information that comes through sensitive feedback in both feeling and sound. The exercise helps you to build your awareness in the same way musicians do to achieve perfect notes in the twisting of a finger on the strings or the pressure of air they pass over the Embouchure hole, controlling the vibration of a column of air. With their bottom lip perfectly applied to the lip plate, sensitively negotiating a perfected distance that's subtly different according to each key change, they use their inbuilt sensitivity to further control the air to total perfection according to their own perfect-pitch hearing.

Planing has little need of too much force, but it does have need for sharpness. I've addressed this many times, but it's no trouble for me to repeat it. There is little need to be "over the work" with upper body mass. If you need to do this, it's not because of resistant wood or stubborn planing work, it's either because you have a dull iron or way too much set. Sensitive setting comers with an appreciation that too much set tends to upwardly rip fibres ahead of the cutting edge's separating cut reaching the lower fibres. Sharpening is the most neglected area of planing work, and we are reluctant to remove the cutting iron to resharpen and then reset the plane again. Only maturity and wisdom will encourage you to sharpen several times in a morning's planing. I'm not saying that sharpening, when you are full-on making, isn't a bit of a nuisance, but this is where wisdom and patience unite to redirect that part of our stubborn nature that needs self-discipline. With a dull iron, and this is undiscussed, the plane rises in every planing stroke from start to end. Two or three things take place. There is a hesitancy as you register the plane's sole at the start of the stroke and as we push forward, the slightest radius developed through wear at the cutting edge, causes the plane to rise and ride the rounded edge even though it is still cutting. As we close out the cut towards the end of the stroke, we apply greater, more confident effort to close out the stroke. The surface usually ends up cambered and when we place the square against the wood for laying out joints, the inaccurate plane work telegraphs in our subsequent efforts. This has a very significant effect on our work. Furthermore, looking at an extended plane iron protruding through the sole face is not just the removal of more wood than is practical, it is leverage against you and that is where the 'ripping' of the grain comes in. It's almost always the impatient nature to our character that causes us to go for heavy plane sets. That said, there are places for it. When the shaving is narrow in width, bevelling a corner, for instance, it's fine to engage with deeper cuts and then lighten up as the width increases. This is just a tactic.

A spokeshave is never referred to as a plane, but a plane it is. Applying the above information to a spokeshave will be good for you as it is the same even though the work is most often quite different. We can often apply a lot more force to a spokeshave and the cuts will still come long well after dullness has reduced the effectiveness of the tool. The spokeshave will often be used for narrower work and is never used for creating a plane is in hand plane work. But whereas sharpness is less essential to green woodworking, it can be absolutely essential in dried-down wood that's been kiln dried for furniture. End-grain oak will never yield a good surface with a dull iron, and stagger-marks will always be the result. To correct this, set the newly sharpened iron to a shallow cut and it will save your work. Additionally, in all I have written here, remover that more staggered surfaces will be the result of friction on the sole of the smoothing tools, so use my rag-in-a-can oiler to reduce friction. Wax polish and candle wax works too, but the can works great.

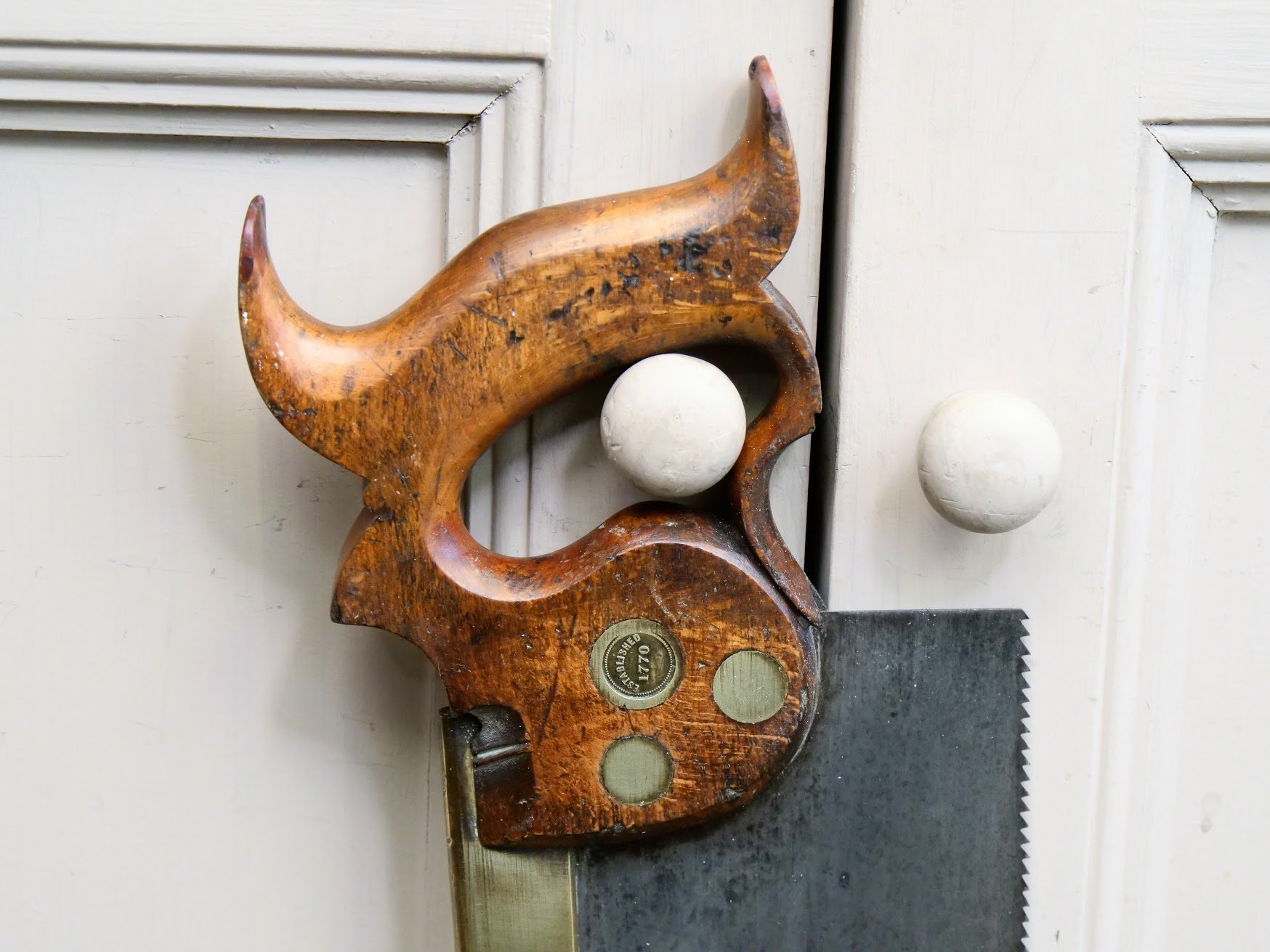

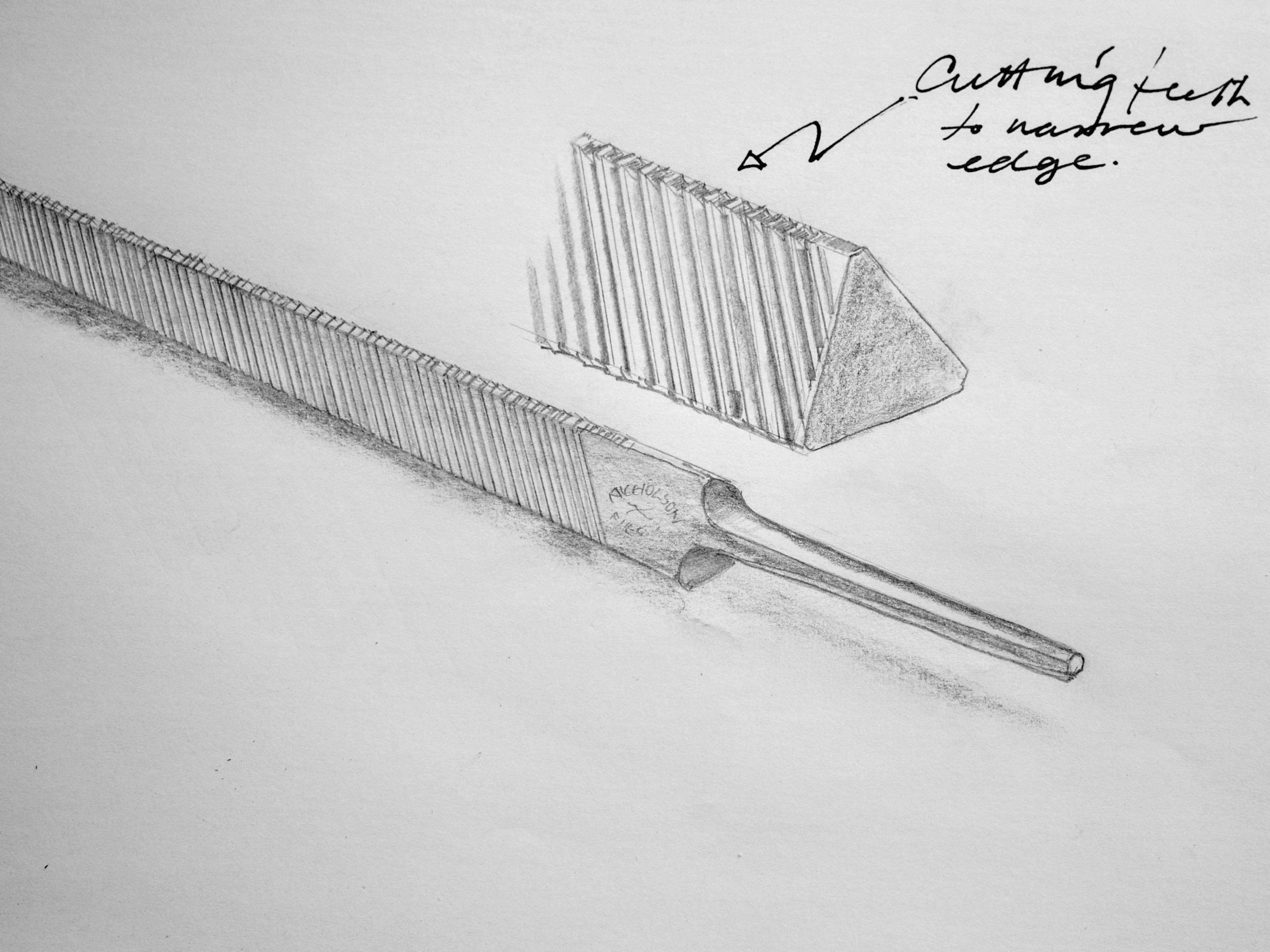

Saw sharpening is another avoided task, and yet I can sharpen any of my saws in under ten minutes. Though they need sharpening much less often than plane irons, they give the best sheering cuts when the teeth have fresh, sharp corners rather than the worn rounded ones. That might sound obvious, but I don't think it is. Almost every saw I have ever picked up belonging to others or having been owned previously by others will be way beyond need of sharpening. That's most;y because people want a ready-to-go saw of the bat, they have no idea how to sharpen anyway and see sharpenable saws as a waste of space. They also have no faith that they could ever sharpen something that looks so complicated to do. Sharpening a saw was the first thing I learned in 1965. I ended up sharpening for the other men, which gave me the early experience needed for the rest of my work life. It doesn't take that much to develop the skill, though. I don't really like it when comments come in to diminish my encouraging words by saying, "Ah, yes, but that's 60 years experience!" or, "It's okay saying that if you've done it all your life." I gained the skills for different saw sizes and types in just a few repeat sharpenings of saws. Furthermore, I am nobody special, just a working, manual worker. I honestly believe anyone can do this if they simply make the decision to buy resharpenable saws early on, along with a couple of good saw files that will most likely keep them in sharp saws for two or three decades.

I sharpen all of my saws with more than 8 points per inch (PPI) for a rip cut, which means that the teeth are four-sided chisel tips rather than three-sided pinnacle ones. Most of these are backsaws, often known as tenon saws. Mine are between 10 and 19 ppi. I do use a modeller's saw with 30 ppi, but rarely do I sharpen them because of the tooth size. Handsaws make up the other saw types I use, and I don't generally buy any throwaway saws, though I own a couple for outdoor garden work so I can keep my bench saws for safe use at the bench.

So we see that exercise achieved through working our wood with hand tools cannot be had by machining wood, which generally eliminates it. It's a matter of choice for most, but not everyone. Any disability from any source may necessitate the use of machines, and I want to be sensitive to that too. I'm thankful now that I pursued handwork instead of taking my ease and machining my wood. I did not realise that my increased strength from planing and sawing would equip me in my later life. My recovery from my broken ribs came quickly and enabled my return to work within a short period of time. The doctors said my injuries would have been worse had I not had the upper-body strength and resilience. Unusual for a man my age!

Comments ()