Volunteering

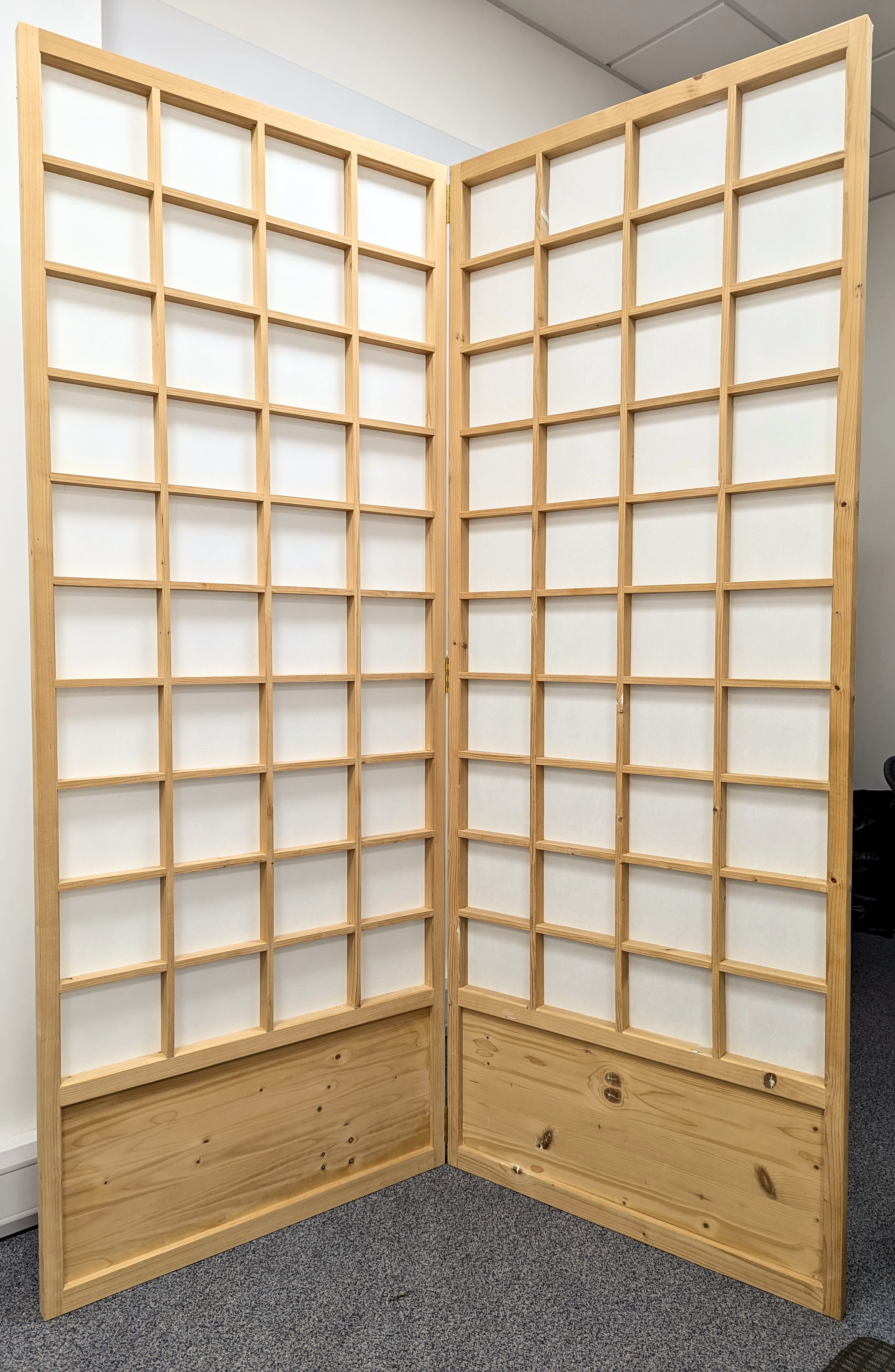

I thought about all of the woodworking joints that I must've made with no use of a machine, along with the few thousands of others I have machined in making my production line products. For several years, I made around 100 walking canes a week using a single mortise and tenon joints, but still realised that this was only a fraction of my hand made versions. Of the hand made ones, 95% will never be seen and never known of. I know this, I can claim way past a hundred thousand hand cut joints in wood. Here's a half decent example of a project with over a hundred hand cut joints from four years ago. Two spruce studs cost £8 (at the time) and the special Shoji paper was £20 per roll but only £4 for this two-panel screen. There is nothing at all difficult or complicated about authentically replicating the Japanese joinery, even when using only Western hand tools. Wood is wood is wood!

We tend to hide our joints and joinery methods within the wood we make our joints from. That is inside its adjacent opposite and partner. i.e. the mortise can totally enclose the tenon with no visible outer, this is common––usually, it will look as though the rail just, well, butts up against the adjacent stile or other cross member. Housings and dado joints can look the same. Looking at the front of a shelf gives no clue and once together, clamped and glued, no one will tell or ever know. The name and the integrity of the maker will always be unknown by any owner and all users. I once dismantled a wardrobe with extremely long sliding dovetails, very accurately made and obviously from the age when no machine was invented to do it too. It was unglued and tight with a couple of nails to prevent it backing out over a couple of centuries.

I'm thinking now of my own work, where I have 'volunteered' such hiddenness into pieces where I could simply have glued or nailed or screwed or all of the above to unite the work together beneath other parts or veneers. When I thought about this and throughout my lifetime of making furniture and joinery and such, there will likely be at the very least a hundred thousand such buried joints for me to own.

This week I did some similar thing. I made a prototype, yes just a prototype, with dovetails that would hold a housing dado in place for the duration. It might be seen, but it will go unnoticed, of that I am certain. Though I volunteered into the making of this, it was indeed a totally unnecessary composition of joints as the corner dovetails would hold no matter what and these joints are within a few inches of the corner dovetails; no way could they ever give? So we see again how we add to our work voluntarily and most likely no one will ever consider what we did with any real insight or understanding, but we simply wanted to volunteer it. So why do such a thing? Well, to actually do what I did on this piece would take ten time longer by machine; no, perhaps twenty times longer. That's because most of it would a tricky set-up to get it right, and that is even if it was possible to do in such tight places. We hand toolists do these things because we can, and we can do it moderately, without fuss and within just four or five minutes. But we also do them to make a point, and we do it sometimes to give us a challenge.

Our volunteering is multifaceted too. We volunteer into harder, higher-demand woodworking, in the same way many health-pursuers do in their distance running, spending their energy going to the gym purely to maintain the quality of their health and so on. Our pursuits are because we value all the multidimensional benefits we can't really get any other way. The combination of physical work and creating our projects means that there is no energy that doesn't make the project. We can make and create, so not one and the same as just keeping fit. We volunteer into using hand tools because it is just extremely good for our physical and mental development, body and mind maintenance and the once highly undervalued quality of life and wellbeing. Something we can achieve doing no other way. You see, with some people, the result is all that they want. For us, our volunteering into the extra work of high-demand making, the added demand is as important if not more so than the result they aim for. The two elements of how we make what we make and the piece we make too is everything we hope for. If the effect making has on us is in any part less than the effect completing the piece has, well, we would just take the easy passage of machining things, and why wouldn't we? You see, someone like me can make a complete coffee table by using machine-only methods in half a day. Yes, I mean about four hours, without stretching anything and especially the truth. Using a power planer and chop saw will give me all the parts planed up four-square and cut to dead lengths in about half- to three-quarters of an hour, no problem. Edge jointing gives me glue up to clamped up in ten more minutes. The joinery will be 15 minutes per corner of two paired-up mortise and tenon joints, so an hour on a mortiser and a tablesaw with a dado stack installed. Now for the belt sander, followed by the random orbit version. Hey presto. Ready for the finish to go on.

It took some crossing over, the day I chose to reduce the machine footprint in my life and increase my workspace by that divesting, and then too the freedom I gained when I did. Those rich in machines, finances and space and so on, and I am not talking at all to commercial makers here, will find their dependency on their luxury items hard to let go of, but as it is with any weightless program, you don't need to do it all at once.

I'd forgotten how I had joined the corners of my Shoji screens and was glad for the short video clip I took that reminded me.

This week, I chose volunteering again. It's never much different for me. I rip my wood by bandsaw, of course I do, I do it for a couple of good reasons, not the least of which is conservation of both my time and my energy. Some may well ask, 'in that case, why don't you use other machines and save myself all the work?' Well, mostly, and I can speak from an experience most others can't, it's to do with my long-term, full-time six decades of six-day-a-week woodworking relying mostly but not wholly on hand tools. This alone gives me choices 95% of woodworkers don't have. I doubt there are too many out there these days who can say such a thing. Be honest! Who do you know that's living and making full-time that started in 1965 and never missed a day of making? Am I boasting? I hope not. I'm kind of on the other side of the experiment now. Did I know that my body would continue to 'volunteer' into ten more years past the sell-by date?

Our lives become hidden in the work we do. We leave it for others to live with, knowing that they will never see the unseen within the fibre of what we've made. It's not uncommon for old men to keep going silently and quietly in the backwaters somewhere, a background workshop at home in the unshared space of reserve. That space has become more critical than ever these days. In those who follow us online, it is a place for recovery. In many lives, the unchosen but worked life is a matter of fact. Their work too is mostly unknown, often hidden in hours of code creativity but non-the-less as valuable and carefully crafted as my own work three-dimensionally in wood. A hundred and fifty years ago, a man like me might have known two hundred other such makers just like themselves in a medium-sized town; people like me, I suppose. More people know other coders and not full-time makers like me these days, I am sure.

I like that my joints remain mostly hidden. Not all of them. Nothing really replaces a dovetail on a dovetailed box, obviating the long-lasting indestructibility of the box. I like that future generations will become all the more bemused by the interlocking of wooden joints, and look forward to seeing if AI will actually succeed in totally replacing me: that they will be sending code to machine answers to their needs. Who knows, they might just send a thought telepathically and that might just be the new skill others will admire.

The composition of joinery reflects the etymology of the word joinery in this: the root of joinery is harmos from which we derive harmony. As a youth in my apprenticeship, the men often referred to the joinery by saying, "Go ahead and marry that joint." That's now gone. I haven't heard it since the latter part of the 1960s. It's a sad loss, really. The saying, now hidden if not completely lost, but I mention it occasionally in the hope that retaining it fondly in my memory, I might just add it to yours.

Becoming a volunteer into what I speak of is not to please other people, but to satisfy your own demands on yourself. You do not need the approval of others in your woodworking, though a genuine critique is helpful and not the same as criticism. We don't suffer from peer-pressure or negative influencers as we mature in our craftwork.

So here I am. It's another Monday to volunteer into, and I think I was born to create and also never know the depression of a Monday-morning feeling. Squaring the wood, even planing my end-grain in readiness, is pure delight. Ten plane strokes surpasses any other method and matches or exceeds any other method, though it isn't quite as fast. My pencil marks glide onto the surfaces as if on a white sheet of paper. How many joints I will be hiding this week is yet to be unseen. As I rode my bike at 5.30 to start my day with writing and panning was more than thrilling as the Maple and London Plane leaves crunched beneath my wheels. It's still dark as I find the different paths, and only a few lights are on in the houses. I like this time because I don't have to fight with cars, extending dog leads, runners and pedestrians. Life is good!

Comments ()