Thinking Glue and Gluing Up

Is watching glue dry the same as watching and waiting for paint to dry; both have a way of postponing progress, when both, in their own way, are actually the progressing action of moving things forward. The inference in the common saying, "It's like watching paint dry." is, of course, that waiting for something you are waiting for in the meantime to happen creates boredom and becomes the ultimate in boring because no further/other action can take place until the painted thing can indeed be touched and until it is dry, only the arrival of the waited-for thing will satisfy the person waiting to get on with life.

And then, who thinks much about glue anyway? Roll it, brush it, smear it; place, push or insert it and apply pressure, and then it's left to be for a few hours. It's not quite like paint, where if you are like me, you end up wondering whether paint shrinks on or stretches away to perfect flatness and the brush marks you left in the surface when you stopped moving it with the brush, are suddenly gone. For the main part, glue is always hidden between two or more component surfaces, never to be seen again in a dried or cured state, it bonds the recipients permanently and is never seen again. And then there's another point: did it cure or did it dry? How did it dry anyway: evaporation, absorption, reaction––what do we know anyway?

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVOH, PVA, or PVAl) is a colourless, odourless and water-soluble synthetic polymer. Hard to believe it, but it was first discovered over a hundred years ago in the early 1920s and is used for a massive range of applications, from laminating two or more panels of glass to create a safety glass to the packaging of all kinds of everyday products to keep them dry and free from contamination. It starts life in powder form, granules, or pellets to then be treated for a wide range of products including our much depended on, PVA glue. In many ways, it is not the glue that is so fascinating, though it's that too, but the effects of the water in the glue influencing the wood fibres and the stickability of the water-soluble plastic and its reaction in the surface and immediate subsurface fibres being glued.

I think that it is true to say that we rarely consider what happens between the two mated surfaces when we reach for the bottle of glue. This *white or yellow liquid has the ability to secure what we have made for decades of daily use; knowing what I know from my daily use of it, I have no reason to believe that it shouldn't last as a bond in wood for centuries into our future and the futures of other lives. We rely on this as a positive outcome that started replacing other glues such as the milk-based Casein in the 1960s and Cascamite, which we made up as needed by adding water to the white powder and mixing for application. It lasted for application but set within a short time, depending on the temperature at the time.

When we use glue as the adhesive that holds our pieces together, we think permanence and enter the realms of permanent expectation. We want to eliminate any possibility of separation over an exceptionally long term. Usually, we are entering our piece into a two-hundred-year expectancy and whereas we do have choices to make, there are not really that many. We might think that this or that PVA is better than the other, and I am sure that there will be some marginal differences, in my 60 years of using PVA I cannot say I have noticed much of any difference and I think that at some stage I may now have used all of them.

In 98% of our gluing, we reach for a PVA glue, and this is the most commonly known and used glue of all. As a water-based and water-soluble-when-wet glue, it supplies the needs of a wide range of users ranging from school crafting classes for fabric and paper and, of course, our woodworking and furniture making. It's the convenience and the long, long shelf life of liquid PVA in a bottle that's ready to go twenty-four-seven that seems to know no equal. As the most popular of all glues used in woodworking, it seems to be the winner among glues. Other glues have gradually been displaced by PVA. I doubt that many will ever go back to animal hide glue because of the inconvenience of making it and keeping it fluid by heat and then having to maintain double boiler kettles for keeping it warm enough for use. Of course, special electric glue pots with accurate temperature control came in to replace the old cast iron kettles of old, but for general woodworking and furniture making the PVA is usually the best choice.

Wood expands and contracts throughout its existence once it's cut from the tree and made into something. The hygroscopic character of wood enables it to change without degrade whenever it comes into contact with water––and that's from any source––and it's the water in the glues that makes our wood hygroscopic. Water moisture in the atmosphere influences our wood all the time to a greater or lesser degree; sometimes noticeably and sometimes not. This takes place, more and less, according to any variation in atmospheric moisture content which in turn influences the surface fibres of the wood and, with any constancy, will increase or decrease the levels of water (moisture content) in the wood. Any uptake of moisture this way increases the size of the wood by causing expansion. Reduce the atmospheric moisture or any other source of water that might influence the wood, and the wood reduces its size by shrinkage. In our woodworking and furniture making, this is usually according to any changes in room temperature. When water molecules are suspended in the surrounding atmosphere they change; adsorbing substances, wood, in our case, become physically changed, e.g. changing in volume, i.e. water's boiling point changes to become steam. For example, a finely dispersed hygroscopic powder, such as a literal sawdust as in actual dust powder, will become clumpy and expand its volume over time due purely because it collected moisture from the surrounding environment.

I walk away from this wondering what colleges teach in the day to day. These glue ups and parting them, the expansion caused by throwing wood premeasured and weighed into a bucket of water is better than reading statistics in charts from a textbook.

Wood's hygroscopic nature, hygroscopy, is the phenomenon of attracting and holding water molecules via either absorption or adsorption from the surrounding environment. Within a glued joint, (that's in the meeting walls or surfaces of the two joint parts) when the glue is water-based and fresh, the wood surfaces meeting one another, and they immediately begin to swell towards one another, moving from the drier inside grain to expand the outer surfaces. Think squeezing into a gap, here. Additionally, as the surface fibres swell, the glue dries and sets within those surface fibres through absorption and to some degree locks those surface fibres into one another so that the glue then serves to hold some degree of its new swollenness and prevents the fibres from a full retreat back into its former self in the manner they would if no glue was present to hold them. The surface fibres interlock at the same time, so in other words, the glue expands the wood and the wood somewhat becomes 'frozen' at this swollen or expanded level, though not altogether, and that is why I prefer joints to retain some surface fibre roughness as in the saw kerf from my hand sawing, etc.

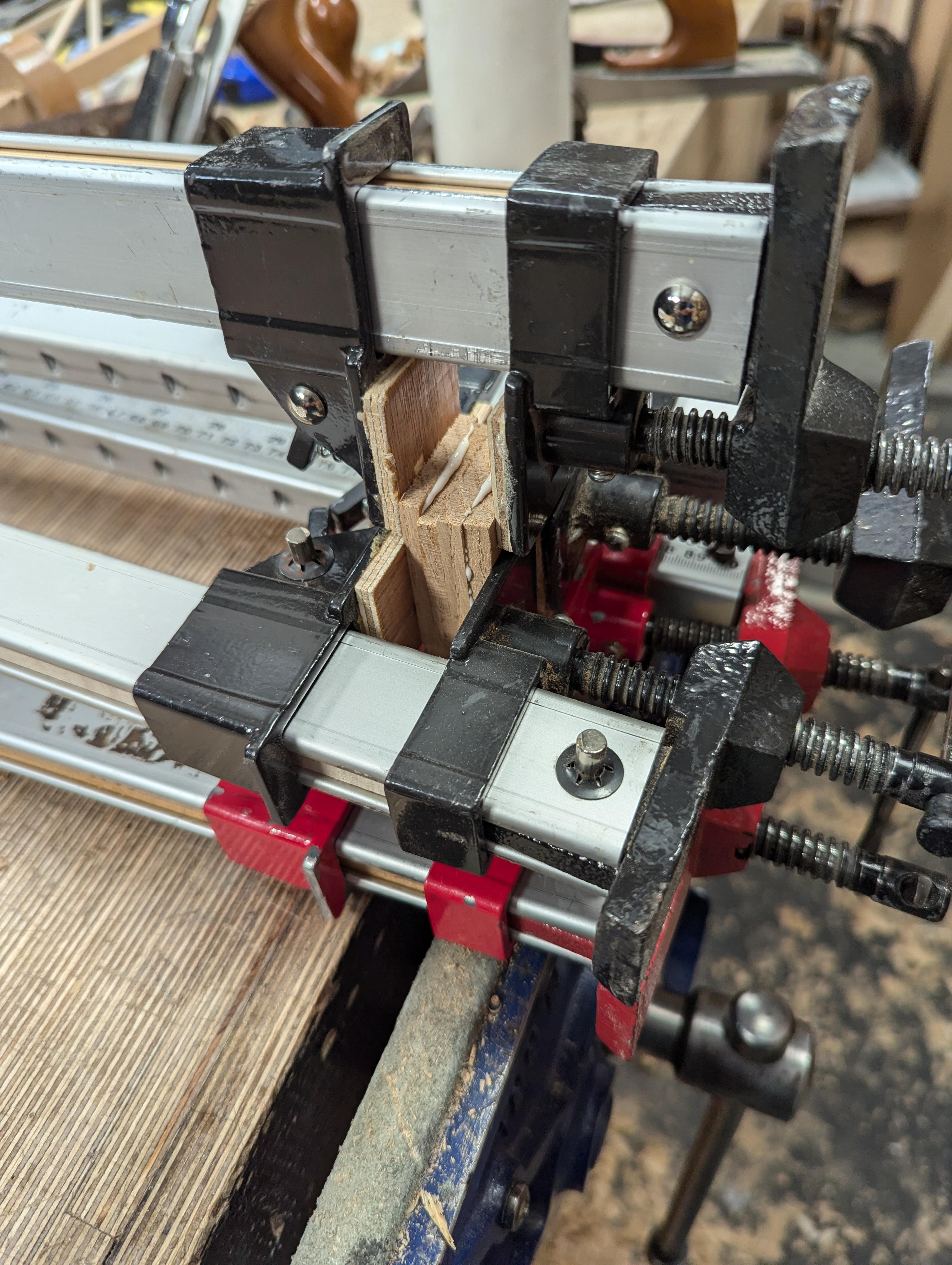

Constraining wood in the immediacy of glue application can prevent too much expansion through moisture uptake. By that, I mean that the very application of PVA as a water-based glue will cause an immediate swelling of the fibres, but subsurface fibres take an extended but still short time to expand so fully as the outer surfaces. The sooner substantive pressure is applied via clamps, vise jaws and such, using cauls or external metal strapping, or using a vacuum bag press, the less wood expansion takes place. Hence, our need to not procrastinate at the point of our gluing up and applying pressure but the need to get the parts inserted without any delay and in that immediacy, applying pressure to close off shoulder lines and restrict joints. Here, also, we see the need for methodical gluing up practices, rehearsals, presets of equipment, etc, to keep all the parts moving throughout the assembly until clamps and such are applied. To some degree, clamps and a vise can and do reduce expansion at the critical points by restricting a fuller expansion over time during drying and such, but this only works if we work efficiently to apply the needed pressure to close off joint lines by pressure; if you apply extra wood on the outsides of the components, cauls, you have some additional measure of control. So, though we have some measure of control from the outside, we don't have too much control of the glue releasing water into the fibres being stuck together. This natural uptake from the glue to both faces is nature itself and generally, it is restricted to water-based glues rather than chemical glues, epoxies and such.

I am never altogether convinced that the glue is stronger than the wood because few people really come to me with tests from the day to day of real working conditions. You can, of course, influence tests and experiments to effect the outcome you want. Researchers do this all the time. We've seen projects from carmakers manipulate their statistics in favour to show better mileage delivery way beyond the capacity of the car they make. If your research depends on industry financing or government aid, then it shouldn't surprise you if they dance to the beat of that drum. Mostly it's job security. If you are selling glue and the whole world of woodworking ends up saying that, "Oh, the glue is always stronger than the wood." without naming the wood type, test conditions and so on, then you better understand that what they are saying may well not be true in most of the conditions we work in.

Taking a closer look at the oak examples above surely showed me in this particular case that the wood was considerably stronger than the glue in that the two examples readily parted quite cleanly, except in the smoothed pieces where some wood did split for a small percentage area of the wood. But it was the rougher surface that held the better in my testing. There wasn't a lot of difference, but it was enough for me to continue the way I glue up, using the rougher surfaces but not dead rough and uneven ones. But who would listen to Paul Sellers in his backwater of real life making in his garage studio in Oxfordshire. Splitting the two examples apart with a 1" chisel, I found the rough-sawn surfaces were harder to separate than the planed smooth ones. And I must say this too, I have known more planed surfaces to separate along glue lines than less smoothed out versions. Taking a coarse sandpaper carefully along edge-jointed edges for a wider glue up of a top does seem to give more 'tooth' within the jointed area, but you need to be careful not to touch the outer corners and round them as this will show in the finished glue line. Also, remember to make sure you blow off or remove any sanded particles, as this can end up a barrier between the glue and the meeting surfaces. Observe that the glue remained on both surfaces, showing me that the glue was indeed weaker than the wood and when you consider that oak is one of the very easiest of woods to split along the grain, that might surprise you all the more.

*In the USA, white glue identifies that this glue is developed more for generally use with fabric and other flexible materials and is designed and engineered to flex in use. Yellow glue is generally used for wood and is more rigid. I like this way of distinguishing the two type.

Comments ()