Ancients and Passed Paths

There was a gentleness about him––a gentle settledness, I'd say, really. His frailness belied the determined outlook of this now shrunken man who said little, but when he spoke, and said what he said, no one else spoke, for after he'd spoken, there was nothing more to be said. I looked at his denim overalls, not jeans, neatly patched on the knees from two decades or more of kneeling to the lower areas of his work. But when you saw the patches, looked at the neatness of the stitching, the aligning of the fabric's grain, you couldn't think, 'patch'. You could only think 'art'.

Who was this man within the now oversized denim bib and brace overalls that seemed to hang freely from him like curtains? His being draped this way reminded me of furniture covers in a closed down room filled with antique pieces. In my eyes, it was the remarkableness of this ancient person, a man filled with such care and concern for detail in all things, that so intrigued me, for this man had survived two world wars and still held within his grasp the hope of futureness for the ensuing world. Age can be a barrier to such looking forward if we see the closing years of life as something ending our input. Bill never seemed to go down that path. Never pitied himself and never new depression,

I have enjoyed two of my granddaughters working in the workshop with me. One of them, I hope, will continue this woodworking education and one day she will realise that it is me that is leading her rather than her telling me how to hold the chisel hammer. I'm almost joking here. She is attentive and learns well and is willing to listen and do according to how she sees me working. The other evening, in the dark, we were going to watch fireworks, and I was trying unsuccessfully to zip up my jacket. "It will be easier in the street light, grandad." I walked over a few feet and it was. She's six on Friday this week.

Bill, steadies himself with a slow lean into the apron of his bench. The vise has become too heavy for him to squeeze the quick release lever to open and close the vise and though he knew it, he still tried first, just in case. We worked together, and I waited for each slow wind to open the jaw over and over throughout the day. On the cold, icy days he was all the slower and his bench was furthest away from the radiator, but he refused to move it nearer to the heat. In the cold, his nose drips, one drop with each revolution of the vise bar. By the late afternoon, he had slowed to a near stop. Living for four-score (80) years takes its toll on a working man. But yet still, he wants to go on, and I listen always for his wisdom.

I wonder now how often he said simple things like, "Bevel up!" and, "Bevel down!" for this or that task. Then there was a, "Flip yer plane round and pull." Suddenly, the grain no longer ripped and tore beneath, and smoothness came stroke on stroke. The gentleness of a gentle man and a gentleman far exceeds the bluster of powerful men who never said sorry, made a joke of the elderly and bulldozed through life with aggression to get their own way. There was no loudness nor lewdness in my old friend, and though I was so young a person, there seemed to be such a high level of mutual respect flowing from one to the other but taught to me by my parents first and reinforced by him in living out his quiet ways. And we shouldn't ignore the passive aggressions hidden in the, 'just jokin' minutes of the day. They're meant to hide demoralizing someone. Controlling them.

I wondered if the two wars he never spoke of conditioned him to never moan or complain despite his arthritic pain, increased short-sightedness and a loss of hearing. "Can you get this splinter out?" He'd ask of me. Handing me a sharp, quarter-inch chisel. I knew he couldn't see it too well, but I knew too his hands were unsteady, shaky, no matter what he did. Though that was the case, his hands traced the fingertips over my planed surfaces and in a split second he'd know if I went with or against the grain. "Hey-up!" He'd say. "Stroking the dog backwards, lad?" He'd whip out his own plane and show me a skewed stroke that remedied my, "Ill-gotten grain!"

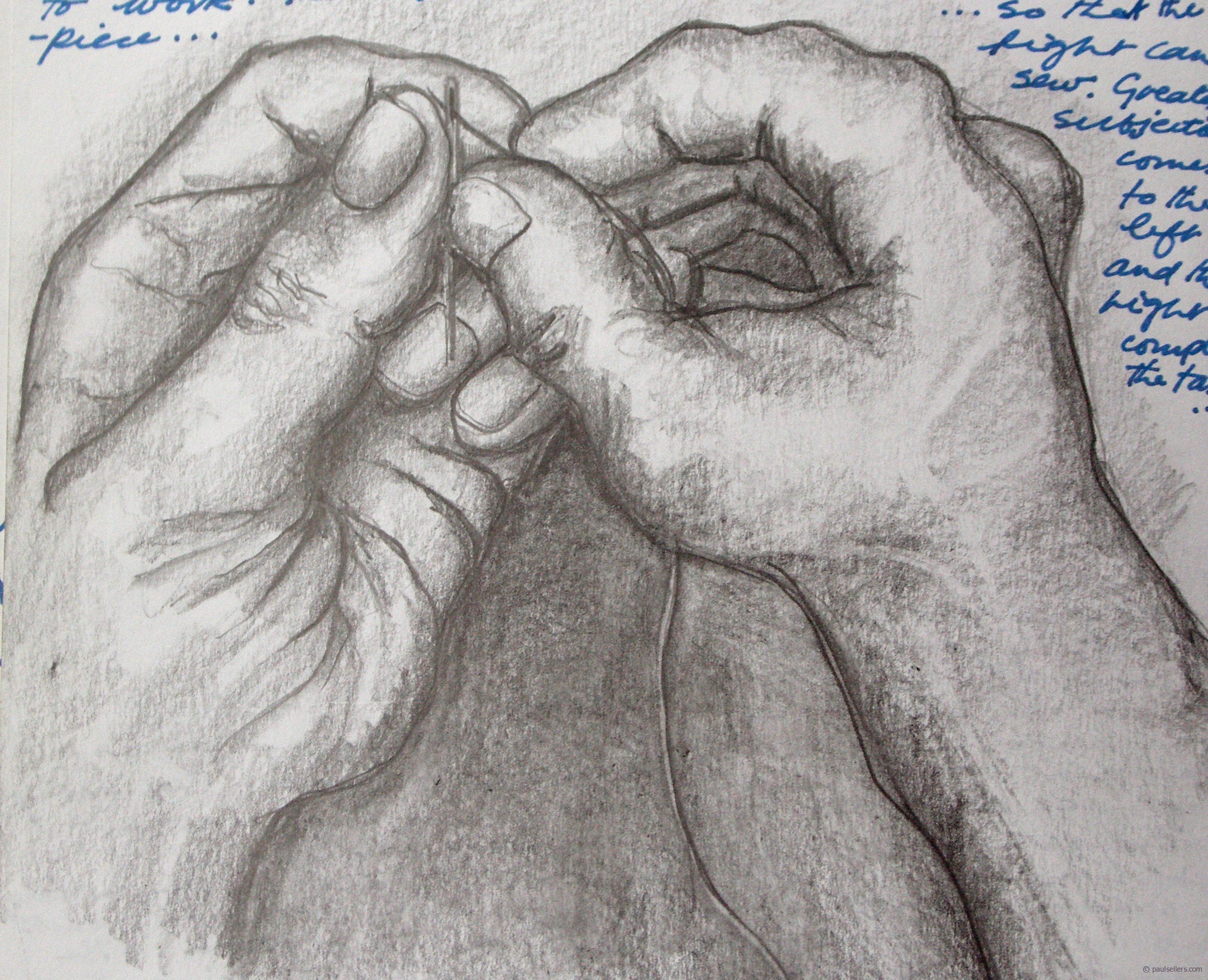

Sewing was another of Bill's skills. From shoe leather to knee and elbow patches, Bill loved to catch that "Stitch in time saves nine." as he always said. And he'd sew for anyone, too. It wasn't sewing that endeared Bill to the hearts of all, though. It was his gentle nature. Even the caustic jealous and crude would ultimately come around when there was a need for Bill. The seeds he'd sewn by his gentle spirit became the seeds sown by his actions without words.

Bill could carry everyone back into the past in a matter of seconds with his opening words, "Ay up, lads!" he'd talk of a horse rearing up in the blacksmith's forge with the smith hanging onto the draft beast's neck to quieten him and "him being swung around like a rag doll." We were all riveted at these impromptu anecdotes that translated us back to the days when horses still pulled wagons and even the odd coach. But it was when he spoke of each of his tools that the magic came. Each tool had its unique story, with many handed down by previous owners he'd worked with. Ebony gauges with inset rings of brass for wear plates. The brass and ebony shone from patina developed over a century of daily use. A nick here and there in the ebony, spoke of a saved finger under a dropped oak door where the gauge stem suspended the door with just enough room to save his fingers. His mallet came from a hedgerow in Gawsworth, Cheshire when he was just fifteen years old, so there we are back in the closing years of the 1800s. But the story was fresh in his ancient mind. It was relived over fifteen minutes, the crosscutting with a bow saw, the splitting of it and the years of waiting for the drying to take down the moisture. He'd pull out the mortise chisel he chopped the mortise with and speak of his replacing the handle for this too. It was the intimacy of a working man's knowledge that was so priceless, though. Making your hand tools was a common enough thing, especially marking out tools like marking and mortise gauges, dovetail templates, marking knives, wooden squares and such. The oak, ash and exotic woods "secretly scavenged" from offcuts the bosses would never let them have even though they would have no use of them.

Bill eventually passed and so too the stories still locked in his brain, but he enrichened my life in a way no one else could today. His bony frame would slowly duck and weave in between the large frames he worked on with his plane to level up the jointed areas. It was the life in and between two world wars that aged him. The use of unknown chemicals and materials even in my time we worked with. I recall how often we made fire doors lined with asbestos we had just cut to size on the tablesaw with no protection at all. I wonder how much more took place like that. Our rich boss, an MP in his day, strutted in and out wearing his fine, hand-made suits cleaning his fingernails as he passed Bill's bench and looking down his nose at a fine man. All he saw was a ragged old man ready for the scrap heap, and "wondered what he was paying him for?"

Comments ()