I'm On the Plane . . .

. . . in fact, by the time you read this, I will have landed the day before, picked up Rosie and be in the workshop working as it will be Tuesday morning, the day after my arrival back in the UK. Portugal has been a welcome break in the sunshine an hour's drive from Lisbon in the small town of Evora. I have always wanted to visit Portugal so this was my first touchdown there for a short visit. I will return to this lovely place when I can.

Culture is the ever-changing dynamic that perpetually shifts and shapes and reshapes any existing status quo as it unites the past to its present and then all that takes place in the split-second take-up of future performance and all that develops. Culture defines every element of the life related to who and what we are and even a brief visit of a few days, as mine has just been, here in Portugal, will reshape something of your life depending much on what you allow but then too all that you don't allow and can do nothing about. The first part to impact me from my visit happened in the first few minutes passengering in an Uber from Lisbon to Evora. It was not the heat of the day nor the blue expanse above the highway, nor was it driving in a left-hand drive car on the opposite side of the road. I am quite used to each one of these from my long life living and working in Texas where we had all of these elements rolled out in the same way.

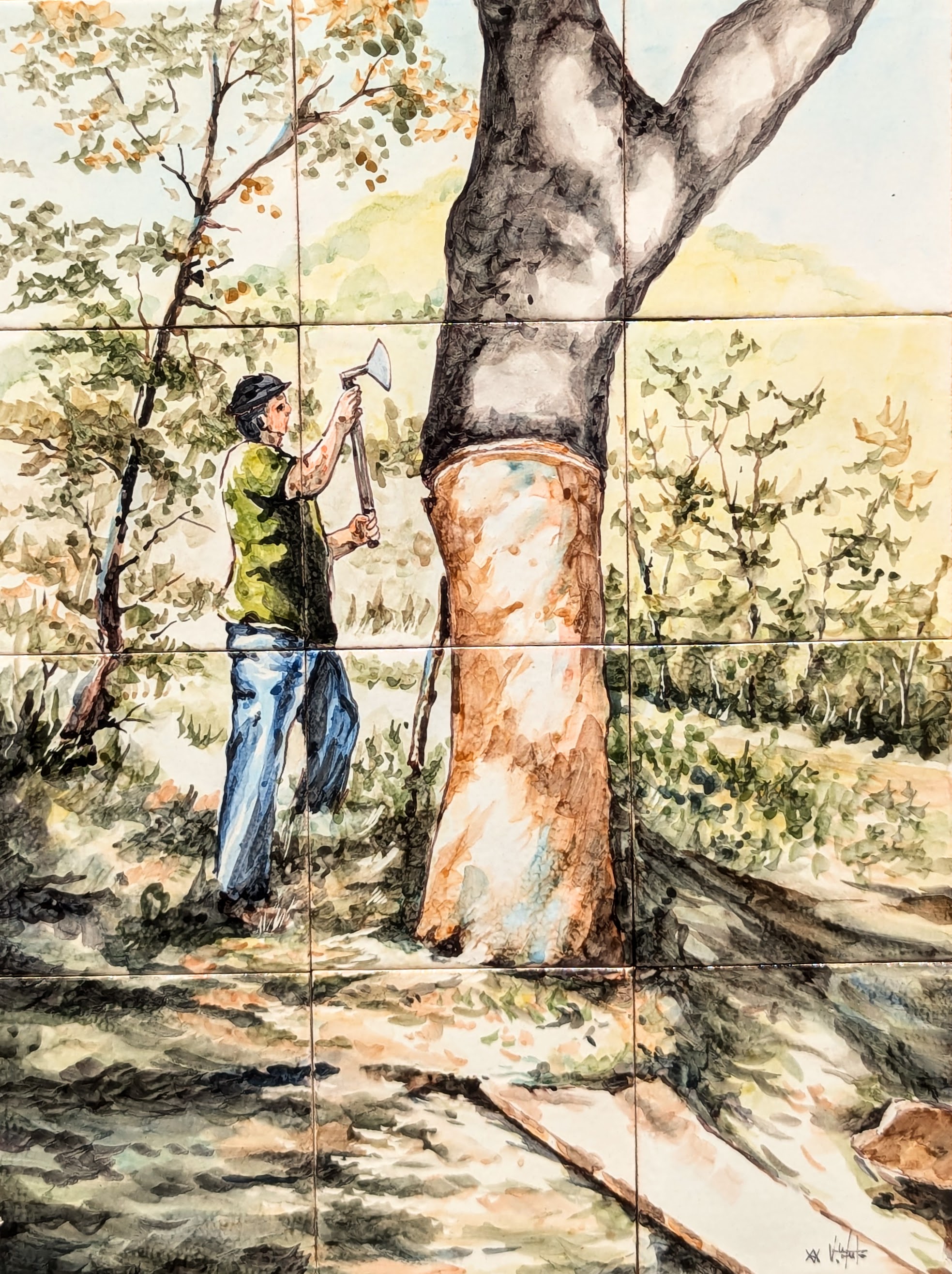

What impacted me was seeing oak forests where the bark was stripped from the stem up to and sometimes above two-thirds up but still holding a full canopy of green showing all trees to be fully alive and thriving despite appearances. You see, Portuguese oaks are a little bit the more unique. These oaks (Quercus suber), are the best trees to make bottle corks from and Portugal is well-famed as the predominant supplier of cork to the wine-making world. Most corks in the world come from these unique oak trees, which are highly protected and regulated to ensure the long-term sustainability of the trees and by that, the supply of wine corks for corking wine bottles. How amazing is that? Imagine a whole, sustainable culture surrounding corks for wine bottling. But cork has a wide range of applications yet the tree just keeps producing and keeps a steady balance between supply and demand simply because the people care for their trees in a proper manner.

I return to the opening words about culture ultimately defining all things about us. I never regard myself as a tourist. I'm here in Portugal to meet my family. When your family is distributed more globally it takes effort to get everyone together. Two years ago it was Austria, before that Berlin, Rheims in France (the unofficial capital of the Champagne wine-growing region where many of the champagne houses are headquartered.) Walking the streets and seeing the ordinary things made of wood and fastened to stone with steel pins is what I do all the time no matter where I am in the world. I look for what ties me to others in my life of woodworking and that often if not mainly includes those who came weeks, months, years, decades and centuries before me.

Over a millennia ago the Romans built the temple to the goddess Diana in Evora. Now whether it was the Romans that actually did the work or that they took the credit for work they demanded others to do I don't know. Without wood, there's a coldness to it so the trees around soften the harshness and harness me in my searches. Shoulderlines and carved medallions are a common thread with some quite rugged joinery still holding on but barely.

It's been decades since I started my de-industrial revolution to reverse some of the damage done to my craft. In the beginning, it was indeed slow going but I persevered against the big boys and I came through to the point I am at today. back then I realised that with three joints and ten hand tools, you could pretty well make anything from wood. Wherever I travel my theory of that time seems to be pretty well proven. The dovetail joint, housing dado joint and the mortise and tenon have survived for millennia and that to me seems quite, quite remarkable.

I look for a form of a dovetail joint or the way an ancient tabletop was anchored by a dovetailed spline also held with dowels. How was it levelled and smoothed so crudely but crudely was the outcome of the work and yet somehow it also felt refined. A Trip Advisor sticker isolates its paired eyes to show me the new message in a pair of not-so-old wooden doors in the 15th-century convent where I am staying, though it's now culturally changed into a comfortable hotel.

I often spend hours on forensic searches and stand staring at an ordinary door rail connected in some way to the door stile until I have absorbed all the hitherto hidden information I need to know the inside details. Shrinkage tells me a lot. A split in a rail might reveal dowels which fix points in stiles and disallow shrinkage in the rails until something gives and becomes a split. These overlaid door panels below display nothing of antiquity but more of our quick-fix, get-it-done-yesterday modernity where rotting parts arrived over decades of neglect and were then covered over with panels that quickly and readily hid the inner deterioration. A quick fix might look good enough to a property owner for five years and as craftmanship has deteriorated through the post-war decades and wages for crafting artisans have increased, this type of repair is evidenced in many cultures on a worldwide scale. Replacing doors for €2,000 plus some even in pine is less amenable than six routed softwood panels, a packet of nails and three hours work. All of Europe faces this kind of decaying construction because restoration, repair, replacement and maintenance were not factored into long-term planning and so are often the neglected cousins of property management and ownership. Rarely are such things budgeted for over the long term because of short-term planning and self-protecting long-term administrators with short-sighted considerations.

Something inside of me wants to remake the doors. Disrepair on such a scale is quite dispiriting and of course, business owners renting a shop and then even the owners too do not want to swallow up what they are in business for the most, making money. I can't take on so great an undertaking but looking at how many woodworkers following me are looking for woodworking to do I could see how a town like Evora (or many others) could organise themselves into guilds to take projects as a means of preserving the inheritance itself as a major part of our culture but then too the training of new woodworkers. Taking on projects perhaps less grand than the spire of Notre Dame Cathedral might seem less worthy but in my world of crat restoration, recognition, craft conservations and much more, it would more than likely be far more monumental. Imagine a central workshop, fully funded and provided for by a town as a centre taking care of repairs to buildings. I know I am not the only one feeling this way. Imagine organising an assembly of skilled and semi-skilled woodworkers into a cohesive work crew and taking on requests at cost and not for profit.

Vintage furniture from a primitive period is not really what we see in the homes of the lofty and privileged. The majority of us don't live in manorial homes and palaces and neither would we want to either. Most of us try and strive to live for realness although I do understand that the influences of the wealthy and privileged are always using unspoken words to say, 'Look at me!' 'You can buy clothes like mine!' 'You can be a famous person kicking a ball around too, or a cook or a lottery winner!' Of course, it's mostly about improving their income as influencers. The richer and more famous ones now rely as much on sponsorship as the skill or ability that got the recognition. A bit different then than the glorified deity bestowed on Diana in millennia past for the goddess Diana, I suppose.

Anyway, back in the land of the real, I am recognising the impact of the Roman Empire's spread as I visit both Paris and Evora and seeing Roman ogees and astragals coming off the ever-more ubiquitous power routers to bring moulding with tell-tale forensic evidence saying this is not that and that is not this. Keeping ourselves real costs us. We're not looking for substitutes for skilled work and working or an easy day in an easy way.

Traveling to Evora I saw oak trees by the many thousands stripped part way from the ground on up and realised without reading or prompting by words that I was looking at a culture that made most of the corks used in bottling wines in the world. The Quercus suber oak figures extremely highly in the Portuguese economy and culturally this tree is rightly revered by the people of Portugal because it reliably keeps the wines of the world safe and has done so for centuries.

I visited a small museum hosting the design and culture of Evora. The artwork interested me yet again and I found several sculptures and other products made from the cork.

On the last day of my travels, I visited a winery and did not know I would fall into the thrall of a new winemaker establishing his own vineyard but amongst a team of support makers on an exploration into the past. Expect the unexpected is a great motto when you visit another country and this one has a past that is steeped in winemaking's hidden gems. The wine is something many people are interested in and I understand the fascination. For me, it is both the process of changing fruit into wine but always important are the people crafting anything that develops a process built on the work of others. The man behind Fitapreta Vinhos is Antonio Macanita. His pathway of discovery, of course, follows his interest in wine but, as it is with any mystery, his path began by stripping away the veils and mysteries of those passing through in life who in one way or another covered up the history with layers of shifting culture by trial and error experiments, modernisations, with only a minimal sense of conservation, preservation or sustainability. I suspect, reading between the lines yet without knowing the man, Antonio Macanita the future at this winery will be quite an uncovering of the past's culture and joining it, not necessarily seamlessly, with a new and exciting future.

Comments ()