Planes Away

I have written quite substantially about the advantages of owning and using different bench planes. Bench planes are the most significant group of planes we use in our everyday bench work. It's that wonderful category of a handful of bevel-down planes we hand tool woodworkers rely on for all our general straightening, levelling and otherwise the initial truing of our wood. Additionally, we use the smoothing and jack planes for all our trimming and fitting wood into wood––frames and drawers into openings, removing swollen stiles to fit again and more in the making of all wooden projects.

It is more than interesting that in mainland Europe, the makers and users there continued using their preferred wooden planes for bench work. Even in the last seventy years, the all-metal versions have been slow to gather very much ground and that's because all metal planes have twice and three times the level of friction on the wood that wood on wood does. Over the longest period, European woodworkers making for a living continued for a century beyond the invention of the cast, all-metal versions and never really transitioned through to fully or even partially adopt the cast-metal options as standard equipment. Not so in the US and British realms. But there was good reason not to. We tend to think that cast metal planes will be the more advanced method of woodworking which is far from true. Look at some wooden planes, perhaps the top one I am using, and then a dozen others that I use, and I doubt that they were used for less than fifty years of daily and continuous use.

Mostly, in my view, it will be what you are first introduced to and what you get started on in your starting-out days that will more likely determine what you continue to use in your woodworking. The truth is this; wooden planes are much lighter on the wood and the secret here is "on the wood". No matter how heavy wooden planes are in the hand, and they are not particularly heavy, as soon as you place them to the wood and push they will always glide weightlessly across the surface as if by some magic and all friction has been removed.

Ultimately, you start to add others to your collection as you grow. Usually, this happens through some ad-hoc venture past a garage sale or flea market. There they are, to be picked up and often for pennies: bargains abandoned by the children of former owners wanting to be rid of "old junk", parental "clutter" and "junk". By this adoption we discover, and usually for good reasons, that every plane type is uniquely different, with one being more effective in this work type over another. I find I do have preferences but not because of the maker name as such but more for the tasks they seem more aptly able to perform and the way they work as such. Sometimes, and I can't always altogether explain the reason in the moment, I quickly switch over to reach for another plane that I might not have touched in a month and I am usually very glad I did. This quick change from one usually makes all the difference.

I have bench planes conveniently housed in a carrier at the right end of my bench well. It's inclined and when my hand slides into a tote the plane comes effortlessly to work in a split second. Three planes sit there, my #4 smoother, my #4 scrub plane and my #5 Jack plane. They come out sequentially according to need. Behind me, on my support table, I have other planes including a second regular #4, a #4 1/2 and a #5 1/2. These too get regular use.

At the end of my bench to my right, I have a couple of wooden planes to use when I want them. Of course, I am talking about bench planes and not the other planes I rely on. One extraordinary plane that doesn't fit the bench plane category but gets used as one is my converted #78 which I adapted to use as a permanent scrub plane. It might seem a crude-looking tool but boy does it work for the rapid reduction of excess material in a wide range of work issues ranging from panel raising to chamfering, scrub planing and so much more.

For me, now, no plane ever made will replace my #4s in Record, Stanley and Woden makes. These are the workhorses I do everything and anything I want to do with them, as much as any other bench plane ever made––possibly much more. By the time I concluded my apprenticeship in the 1960s wooden planes were all but gone in Britain but it was not because they didn't work and work exceptionally well. Though wooden planes were still plentiful, replacing them at a cost-effective price for retail became much more difficult because demand was much, much less. Industrial machining in every realm of woodworking including amateur shops rendered them obsolete. Who on earth with any sense would want to hand plane and hand saw their wood using primitive methods like that? And power sanding the machine textures left in the wood just got better, easier and more predictable. Switching out a disc or a belt in split seconds took you from 80-grit, deep sanding to 350-grit, silky smoothness in a few consecutive passes. Why plane?

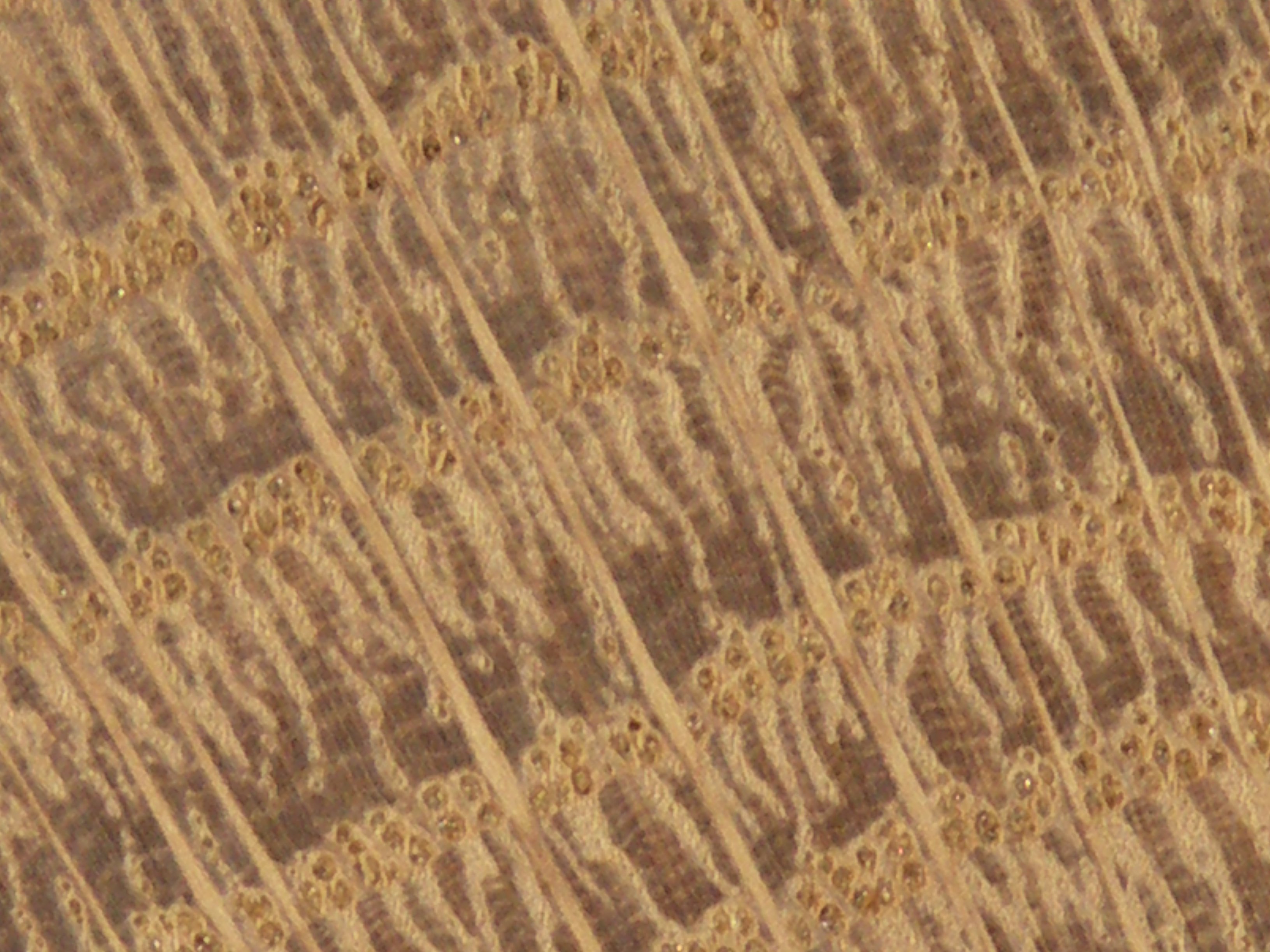

I think that that should be considered. Sanding changes the texture of the surface of the wood. Whereas both feel supremely smooth, a sanded surface lacks the crispness you get from a planed one if and when the plane iron was sharpened to 10,000 grit. The difference defies words. The sanded edges inevitably round the corners as by its very nature, abrading inevitably abrades everything in its path to the degree of unevenness the particulate size and type determines. The planed edge always has a crispness to it you cannot get by sanding with abrasive discs and belts although there are tricks to get that even from a random-orbit sander. But, too, the precision of hand planing is remarkable. Taking off an even thou'-of-an-inch or millimetre is well within reach in the hands of an experienced craftsman.

The investment the inventor and developer Leonard Bailey, together with the Stanley Rule and Level Co, made into the development of their bench plane series of eight-plus bench plane lengths was so good no other plane maker then or since came close to bettering the mechanical functionality and quality of the Bailey-pattern plane. It was so good that any other makers of Leonard Bailey's work could only offer knock-off copies. In the details, they never really offered anything that improved the plane even though they boasted and still boast to that end. Rather than inventing anything to change the dynamism of the plane, they merely offered tighter tolerances that actually encumbered the plane as such engineering often does. Think sloppy gearsticks of a well-worn 1960s Morris Minor, how you slipped the gearstick from second to third half a minute before it engaged and how well that worked for those of us who knew it. I can use the #4 plain-Jane plane version for making raised panels and scrub planing over and above general trimming, refining and truing the wood they are confidently known for. It's a strange assumption that somehow saw the transition of buyers buying all-metal versions they rejected throughout the 20th century. Someone, somehow pursuaded them that expensive versions would suddenly bridge the gap to translate them from unskilled outcomes to skilled ones––that the tools they were using, those unsophisticated primitive ones, were the real problem and nothing to do with any lack of skill––buy a tool ready to go straight from the box and all skills would magic their way into their lives. But no one told them that bench planes would be high-demand tools and high-demand for the rest of their lives because every time you sharpen them you must remove and install different components every time and that this can happen ten or even more times in a day if you are using a plane throughout the day. Sharpening and setting are maintenance tasks and you cannot have one without the other. 99% of good planing outcomes revolve around the sharpness and set of the plane. Once you see that and accept the reality of it you are on your way to good planing practice with pretty much guaranteed outcomes every time you use it. Of course, we believe that better-engineered tools in iron will automatically be better than vintage versions and it makes sense to think that way even if the reality is the opposite. It is unlikely that any modern user of all metal planes would or could ever match the quality of work the wooden plane users accomplished. It's not that they can't. I don't believe that. there are many reasons that they never will, not the least of which quite simply is the loss of skills. I believe that there are makers who could achieve the same results but that they would more than likely take ten times longer to do so.

When I read someone saying, "You get better control and weight to achieve a higher degree of control using heavy metal planes." I tend to think more 'bull-in-a-china-shop' than a refiner of fine work. Most often there will be a sale behind such words. When the selling dynamic hovers in the background I find the informant less trustworthy. My thoughts on that are the same as to those driving massive, single occupancy four-by-four so-called SUVs as city slickers where image and privilege are everything but the road-hogging consequences mean nothing. A heavy plane usually relies on mass and muscle to push things through and for short bursts of work they are fine but using a plane as much as I do it just doesn't work. Add to that the friction of weight and body mass to the sole surface and it will indeed take much muscle mass to muscle through for a result. In 60 years of daily, full-time all-day woodworking five and six days a week I have been able to do all my planing work with two quite basic #4 and a #5 planes.

I often read and hear the term, "My go-to. . . this or that is this or that." And whereas we Brits use 10 words to the American one, there is a difference between choosing one plane over another that minimalist terminology never quite captures. My 'Go-To' tools are rarely to the exclusion of others in the same way I choose a collection of words for a sentence that aptly describes what I prefer and do rather than copycat others. In recent video episodes we made I chose wooden Jack planes to level and true my oak for the two projects in oak drawers. I felt these planes, though perhaps even slightly weightier to lift to task, suddenly change on the wood to float like a dream and feel even less than half the weight of any regular Stanley #5 as they engage the wood. What saddens me is this. Less than the smallest fraction of a per cent of woodworkers will ever experience a well-set and sharpened wooden plane just to understand what I am saying.

There is no doubt that Asian and European woodworkers retained what worked exceptionally well for them and even, dare I say it, worked even more efficiently than any all-metal version. I liken this outcome to the probability that machining wood became more acceptable to competitive business owners than using primitive hand tools. We see a direct correlation between advancing industrialism and the demise of handwork and hand tools on every continent and the destructive forces of industrialisation overwhelmed all crafts. But I think that it is important to understand that industrialising life is negative progress for the majority who became merely owned by the industrial wealthy and had to give in to the demands imposed on them through the possibility and probability of becoming impoverished if they didn't accept what they called "progress". For it wasn't that hand tools didn't work and work well, it was that they didn't keep pace with industrialism, consumerism and the demand for the ever-unfolding ever-changing entity now called 'the economy'. No longer the simpler life of self-sufficiency and sustainability. The demands surrounding ever-cheaper goods forced everyone to not only become a part of the mechanism, they had to somehow embrace it. Of the dangling of consumerist carrots, there is no end. And then for engineers to remain in business there is no point inventing new stuff when you can simply copy what was already designed and invested in by others a century or more earlier. That is what we mostly do after all. And if we can convince our audience that we've engineered out the flaws of earlier models to present something better then we eliminate the need for research and development. All we need is the better mousetrap, right? Well, not quite? Just as no metal plane ever bettered the wooden one, no heavy metal planes bettered the lighter-weight ones either. Such facts as these will eventually be lost in the belief that the vintage models were abandoned because they were indeed believed tobe bettered because, well, we have to be evolving into something ever-better.

When you do as much hand work as I do in any given day you also look for economical use of your body and the tools you use. You want a direct correlation between the waste you remove and the time it takes to maintain a functional tool like a plane that needs immediate and responsive adjustment minute by minute. Clunky heavyweights cannot give you that so it is an evolving process that led to the evolution of the Stanley Bailey-pattern plane that cut the excesses of heavy bodies and thick cutting irons in the wooden British planes and went for ease of sharpening and functionality on the job. You have watched me making thousands of videos and hundreds of pieces of furniture in hardwoods and softwoods. Name one of them, or posts on my blogs, when or where you have seen me reach for a heavyweight plane to tame any aspect of my woodworking. Why haven't I? I simply do what works and works best. But more than that, those following want to know the simplest ways that woodworking works. I keep things practical and simple.

If I only had access to the above planes to flatten boards for a tabletop or true-up four-by-fours for table legs my so-said "Go-to" (and that's the last time I will ever use this lower-grade term) plane would not be among them. If this was what was offered and I had to choose one for the task, it would be the wooden top version even though I do enjoy owning the other types. The ratio of use might be ten to one for the wooden one and then equally for the other two but you'll get substantially greater success on planing flat wood with the Bailey-pattern bevel-down bench plane than you will with the Veritas simply because low-angle bevel-ups fair less well and tend to tear the grain wherever you get rising grain in opposition to the planing direction. So, the first choice is the wooden version, the second the Woden and the third the Veritas, but remember I am talking about general planing of face grain here.

You adjust yourself to enjoy the different characteristics of various bench planes. The question for me ultimately revolves around ease of use and that's because I use them so much more than most other users. The plainest version of the original Stanley #4 smoothing plane is a perfect design for an all-metal plane and no modern plane maker has improved its functionality in any way and may well have impaired its performance with over-engineered intolerances. How about that!

Some woodworkers new to the craft will find the British wooden 'block' of a plane cumbersome and awkward to manage balance-wise at first but you soon get used to managing it if you persevere and give it a fair chance.

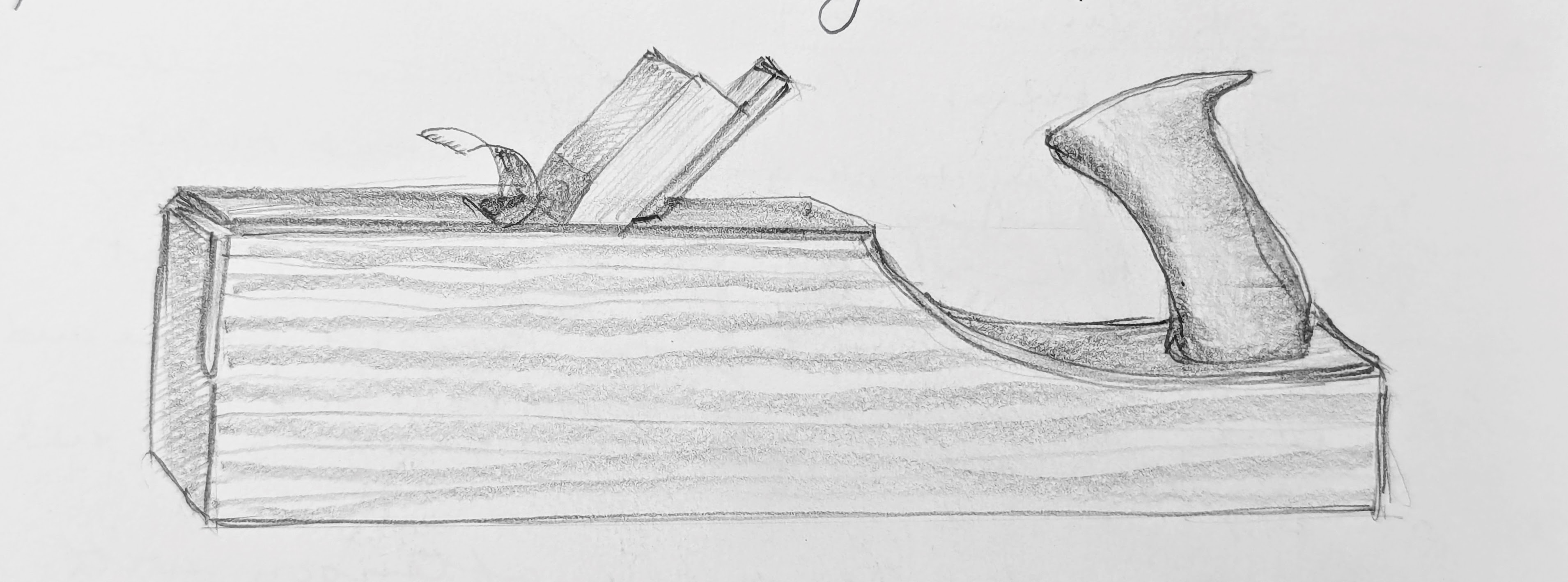

The razee versions are rarer and this type lowers the rear tote for a more direct centre-of-thrust nearer to the catch-point and follow-up thrusting of the plane-stroke cutting edge into the wood. I am always curious as to why plane owners didn't lower the latter third of their regular planes like this because it makes a big difference. I have seen a few theories as to the term 'razee' used but prefer the etymological version meaning to reduce or scrape lower, usually by abrasion.

Comments ()