Drying Down or Drying Up

There really is no one measure-fits-all all wood types when it comes to its moisture content. Green wood in the tree at the point of severance from its root can vary between around 30 to 300 per cent depending on the wood or tree type, the location of moisture in the stem and the season of the year. We woodworkers don't need to know too much about this unless we are logging our own wood. When we do concern ourselves with moisture or water in the wood when we start to consider using this and that piece for an upcoming intention to make something from it. Dense-grained wood in our temperate regions will be somewhere between 6––25% with an average of around 12––15%. It's the local conditions of air temperature and relative humidity that dictate the final moisture levels in our wood. Controlling the environment we work in will impact our wood. This is not always easy for us.

My wood goes into a special dry-time period set aside as my period of acclimation. Is acclimation the same as acclimatisation (use a 'z' instead of 's' in the US)? No. One is a result and the other a process. Acclimation is a result of being accustomed to a new climate or condition. My woods change in different environments. My workshop is relatively dry compared to the house we are making furniture for. My tighter tolerances for inset doors and drawers have resulted in my needing to take remedial action later in the day when the furniture has been placed. The drawer sides expanded sufficiently to make them unopenable. One of the side cabinets in the dining room expanded so much that I needed to use considerable leverage to remove one of the drawers. It's one thing drying my wood down further in my climate-controlled low-humidity garage space and another taking into a home where the daily life of a family showering, cooking, breathing, wet clothes from rainy seasons and such influence to moisture levels of the atmosphere so markedly. But still, it is a good thing to work with dry wood and be prepared to either design accordingly or go in later and ease whatever needs a shaving off somewhere. Because we only work in solid wood we must be aware that wood will indeed swell and contract in our homes. rarely can we truly control the atmospheric moisture content without permanently using a dehumidifier. I take two gallons of water out of the house in a given day at this time of year. Even the MDF doors installed by the builders swell and stick if I don't take the steps to remove some of the atmospheric moisture (AMC). We don't have winters cold enough to eliminate AMC in the surrounding world around our homes; from here on, until summer 2024, we will indeed be wet even if it's sunshine every day.

I am making some boxes from pallet wood. This pallet came under a recent intake for stocking my book Essential Woodworking Hand Tools. I often use a jigsaw to remove the riser blocks which go as firewood to friends with wood-burning stoves. Drying this wood down, even more, ensures the wood can be trued and made ready for joinery with minimal likelihood of further distortion as I work the wood.

The bandsaw is my thicknesser (thicknesser planer machine) of sorts; unifying the thickness means just a few shavings for cleaning up saw kerf.

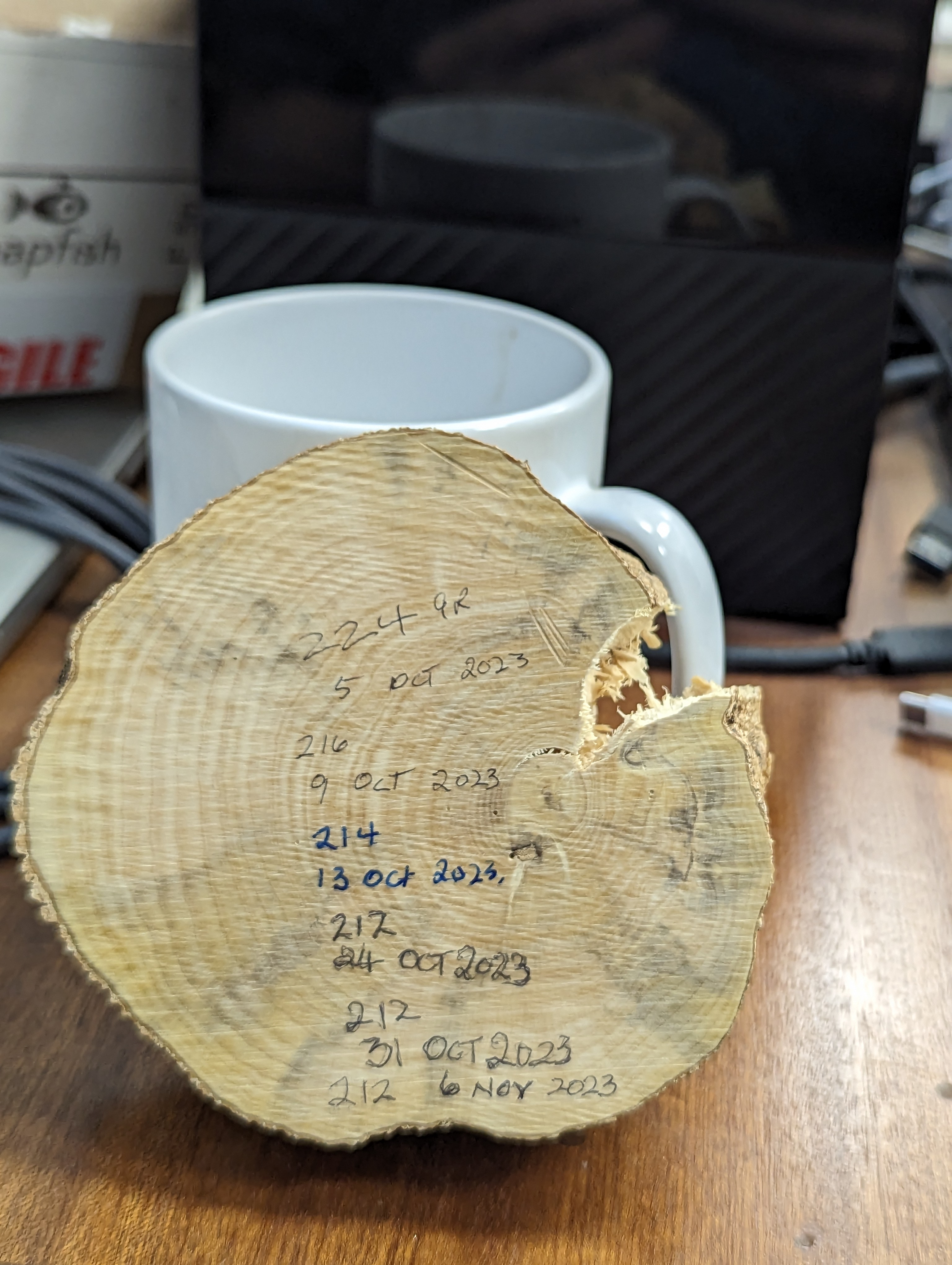

This randomised stacking is less randomised than it looks. I built it up for free airflow in and around the box pieces to bring down any moisture levels though it might well increase too if the weather is against me. I measure the height of the tallest point at the beginning and then check it at the same points every other day to see if the height increases or decreases. Usually, any difference will show on the second or third day and then on through the period of exposure in the controlled environment.

Within two weeks the wood pile lessened in height by half an inch over the 20" distance and then remained the same for three days. My wood was ready.

Stacking the wood this way magnified the expansion so by dividing it by the number of pieces I could see that each 3" wide board expanded 1/8" through taking up atmospheric moisture in its previously uncontrolled conditions. This amount will indeed affect the joinery as of course, the thickness will become apparent when any shrinkage (or future expansion) will show around the dovetail lines of interlocked engagement.

Another method I use is to weigh my wood if indeed it is for smaller sections. Kitchen scales do well for this though I have also used bathroom scales for planks stood on end too. In this case, I want to be sure my wood engraving block was dried down to its maximum. I was patient and it proved right to be. Weighing wood is not an uncommon practice for me as well as for others as it works so well and so accurately.

I do have a moisture meter for steering me when I go to buy. It's an immediate reading even though not a true result of what you actually get throughout a board or a batch of wood. In this case, I used it to simply confirm my weighing on the kitchen scales. Things were moving the right direction for a few days until there was no more reduction. my wood was ready for engraving. What I was trying to avoid and did so successfully was the wood block cracking after preparing it for engraving which can take many weeks of work.

I almost always take my wood into my climate-controlled garage to acclimate. You will usually see it hovering against the back wall for a week and more before I start a new build. It's worked well for my working. It may be a luxury to have a controlled environment but whereas a tablesaw is an essential machine for a machinist woodworker I consider good air control beats that need hands down here in the UK. Let's not talk about Houston!

If you want to, the best acclimatisation will ultimately be in the room where the piece will finally come to rest be that the bedroom, dining kitchen or wherever if indeed it is going into a house. Airconditioning generally keeps things at a constant as will using other means of climate control but of course, rarely does the shop in which the work will take place remain at a comparable level and especially is this so when the work takes weeks or even months and years. The US is a nightmare for makers whereas surprisingly the UK is not. Make a piece in Houston and send it to West Texas and you've got some major issues with severe shrinkage and vice versa send it the other way and within a day not a single drawer will open if it is indeed recessed. hence the development of overlaid doors and drawer fronts developed in and for the USA.

Comments ()