Being Real With Each Other

I wrote recently on beech wood and spoke of what I might see and describe as more soulless methods of making in the sense and mix of it giving very little if any sensory feedback. It wasn't to open a conversation so much as to try to explain why we hand-tool woodworkers handle our materials of wood so very differently and why we need to actually understand it and relate to it differently too. Of course, hand tools can be as soulless as any machine when used as blunt and dulled instruments by blunt and dulled minds. But when used with ultimate sensitivity and sharpness there is a dynamic with hand tools that's not needed as any part of a machining process for wood. For those of us working only or mainly with hand tools, this information becomes key to how and why we work so connectedly to our wood and the hand tools that work it. Ever-increasingly, our sensitivities become more finely attuned to our working and prove essential to the success we strive for as we grow and cultivate our skillfulness along with the awareness needed to make the senses work well for us. We spin and skew bench planes of different types and sizes in a heartbeat and by this we avoid tear-out, yes, but, more than that, we're optimising those skewings and twists for the premium cuts that intentionally and hopefully leave a glass-like finish wherever possible and no matter the wood. For the main part, most people working wood these days are most unlikely to have known this level of performance and outcome and this is because it's most unlikely that they have indeed never touched a hand-planed surface in their life though they might well think they have.

In the day-to-day, I use different scrapers reliably and lift one or the other in moments of seamless working where with flexed fingers the flaws are erased in two or three swipes. Sanding usually roughens the surface of my work with the planes and scrapers and doesn't, cannot, technically smooth it though it may well feel smoother. Mostly this will be no more than the dust between the fingertips and the wood although power-sanding with a random-orbit sander will give an acceptably fine and smooth surface ready for finish. Why do I say this? Well, if you sharpen your plane to 10,000 grit how come the wood's surface is then less smooth than the 250-grit sandpaper you used? As I said, mostly it's the dust between the wood and your fingers that reduces friction and makes things feel smoother. There is a place for sanding though. I use it to sand the surface rough for adhesion of my wood finish and not to smooth it. Sanding in general, doesn't true wood and the plane always will when done well with a sharp cutting edge. How about that for a concept to be learned when all of our lives we have been told that sandpaper smooths wood? Mostly it just smooths wood when hand tools like planes and chisels are not used.

The twist of our chisels to split grain and pare-cut second by second with and across the grain allows grain speak-back we rely on to guide us by grain-pull, grain-ease, leverage and sound. By all of this we micro-shift, adjust angles and present our bodies to absorb change and thereby vary direction, pressure as though the chisel is the mouth that speaks and serves as a total extension for our fingers, hands, arms and hearing too to meet the demand. The muscle-mass of shoulders lock on to follow through and an angle so precise delivers the smoothest pare cuts no other method of woodworking can. Our knifewalls stop fibre fracture occurring in the wrong places by allowing the separation of shorter 'straws' of fibre to be lifted out. This is not who we were but who we've become over a number of weeks, months and years. We have no gymnasium for no gymnasium is ever equipped to produce the dynamism we need but we work out in ways no other woodworking methods can possibly offer either. If we don't do this, have command of our bodies, it will result in poor levels of workmanship and our sensitivity is key to every twist, thrust, pull and turn of a cutting edge.

I like that waste in lengths falls from the saw to the bench and floor; chunks are the norm and then shavings as long as my arm settle around my feet yet cause no dust, need no extraction, there's no screaming, burning and zero apprehension. Of course, machining wood must cut the waste away by a million micro-cuts to create minute particles of sawdust and short chips to remove them at speed to extract them. In my world of hand making, I can grab my waste by the handfuls and take my waste to neighbours for fire starting and stove heat. A machine can only work wood by cuts resulting in the longest chips being no more than a few small millimetres. A machinist works always in thrust-pushing to engage the wood to the powerfeed and align it to follow a path central to the planer or tablesaw––there is no reverse, no turning back or turning around and or sideswipes. It legalistically goes, with or against the grain whether good or bad, right or wrong. Not much or even anything sentient about it. Of course, the wood will usually come out flat, parallel and with almost no effort from the machine worker. Much less to think about really whereas for hand work it will be a totally immersive experience throughout the day.

I haven't put this out to open up a discussion that would most likely be fruitless. My defense of handwork in woodworking is to dismantle any and all attitudes coming from professionals over the decades saying that you cannot make a living from woodworking by hand methods. That depends on who you are. I have no problem and one of my previous blogs prved that you could if you have the drive and skills. I present this and that from what I now know from my six decades experiencing the most comprehensive ways in a day-to-day-life of working wood. I've worked equally in both worlds of machining and hand tool working. I absolutely understand the reasons many people rely on their work using machines; why they use them throughout their workday if they make woodwork for their living. It's an unfortunate thing that most professionals don't believe that handwork will indeed deliver options they might never have understood, practiced or trained themselves in and so decided never to master handwork. It is NOT to criticise anyone or indeed anything but that in any way. What I do is merely to explain that there is almost no connection between the two methods and that there is much more to hand tools than simply comparing the speed and delivery of machines used in industry to hand tool methods. I do all of what I do because there is a very significant and important 'missing link' in information that no longer comes from the masters of old immersed daily in the craft to the boy awaiting direction, instruction and supervision under a watchful eye.

In times past an apprentice grew as a supervised novice over a number of years and facts were passed down in an exchange we will not see again. Such knowledge was work-based at the bench and could not be something read up on in a book or in a magazine. I'm not talking about basic facts. The kind of thing you get from a magazine or a book. It's the physics of working that I'm trying to express. The days of bona fide apprenticeships as in times past are very much gone no matter what governments and educators may say. At age sixteen I saw a man take a single sweep with a one-inch wide chisel and in that single sweep cleaned up every ounce of bandsaw kerf from the inside of a cove but the bevel of the chisel was uppermost. Imagine, all saw kerf removed and the finish was as silk.

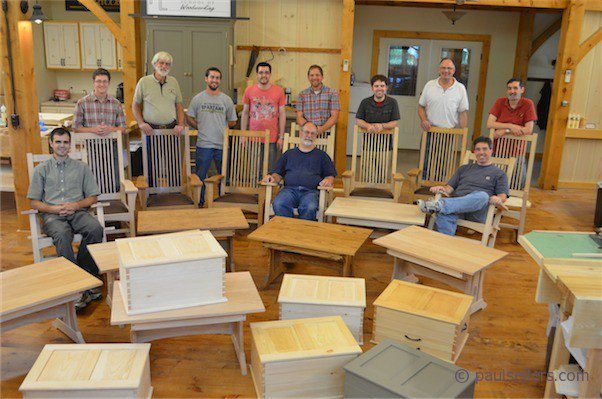

. . . John's rocking chair below is made from highly figured elm and is meticulously constructed in the finest workmanship With every component planed and jointed by hand only.

Apprenticeships in the real sense and strength of the word no longer exist in the fullness they once did. This sad reality occurred mainly because college course training displaced bona fide apprenticeships thinking it could better what ordinary workmen passed so willingly and capably from one generation to the next. These college courses offer very little more than what can be gleaned from reading just a few books or magazines but job security is mostly about meeting the industry needs by box ticking and common sense health and safety; something any parent could teach usually, the core information I speak of is what I am writing and filming day on day, week on week, month on month and year on year. Hand tool woodworking is not old-fashioned, archaic or old-school working. It's the current technology of centuries past that holds just as good for us today as it did in those past centuries and we simply extracted what worked best and kept what worked best for our current work that's all. Do we have to abandon machines and technology though? That's just silly––of course not. If we can afford the money and space for both then those that want to can. I choose not to having been content for seasons in both camps for decades (more than most) I chose what I have purely from experience and decided that this was indeed me. From that I encouraged others to simply pursue what I considered would best equip them for a rather more fulfilled life using their own developed skills and power for a variety of really good reasons. But we can run our personal training in tandem without compromising anything; it is, however, important to see that machining wood does in no way equip you for handwork with hand tools. The two are barely related, really. The connection can be made by categorising one in one camp and the other squarely away in the other. The now more populist term of hybrid is really not new at all, it's what we've done for two centuries but never needed to described it so.

Even well-intended books and articles cannot articulate feeling and especially the feelings of a working artisan who spent a lifetime working his wood but never wrote down what the wood spoke to him in the doing of it. Consider this though. That's like millions of woodworkers throughout the pre-conveyor belt world of earlier centuries. Take this and add in the differences between hundreds of species of wood, the different cuts made into it and then the tool types used and the tools used that make them work. By this, you will understand how comprehensive this man-to-apprentice transfer of knowledge and work-based information was in the pre-internet days when the information carried much deeper meaning for the apprentice relating to the men of the day must by necessity have been. With apprenticeship and the whole intimacy of working the wood by hand, you have the most incredible shortfall imaginable in the training of a future hand tool woodworker. Thirty or so years ago this was dismissed because, well, who was going to hand plane a piece of wood anyway? Who was going to rip and thickness their wood by hand? I know, in the 1980s, I thought the same. Wood magazines back then always showed power routers and tablesaws on the front covers along with the gladiator gear and posings and 95% of the content surrounded machining wood. The change came by a gradual recognition that machines were really limiting, highly invasive offering ease and speed for some things but little in versatility. They were also extremely noisy, messy, highly dangerous and any outcome was always clouded by how they really limited our work, how intrusive they were to our moving lucidity and calmness through our working hours. Believe it or not, amateur woodworkers actually like the concept of physical, high-demand work in a quiet atmosphere. They are generally more knowledgeable than professionals too. You see, we want the feel of muscle and sinew stretched by the mind to make woodwork with hand tools and with hand tools we can afford to give time and space to.

I often think of something I have seen creep into woodworking in recent decades. What I like about my work and the direction I finally chose to go in is the realness of my craft and the working knowledge of it. Watch me working and you will usually see me using a handful of hand tools you can buy for around £20 a piece and less; a hundred pounds gets you started and usually these are the tools you will rely on for 90% of all you ever make in the future. Just sayin'!

I am not sure why but many woodworkers on the net with any kind of following have created an image that in no way really validates them because, well, it's obviously an unlived and contrived way. A backdrop of several thousand pounds or dollars worth of hand planes isn't really exemplary of much more than conjuring up an image they perceive to be validating. Let me give you an example.

When I was 18 years old I had been rock climbing for five years having trained at an Outdoor Pursuits Centre in Hope Valley, Derbyshire and being taken on as a volunteer aide by the team there. I became a competent climber with exactly the weight-to-strength ratio needed to climb hard climbs as a freestyle climber. I teamed up with an old school friend and he bought into the gear because of his family wealth. When we walked up to the crags and met other climbers along the way he was always left out of the framework of real climbers whereas I got the nods. My gear was far from fancy because mostly it was secondhand, old and well-worn in both senses of the word. One day we walked along and he commented, "How come you look so much like a climber and here I am with all the best gear and nobody says 'Hi' like they do to you"?' The difference was that he wanted both the image of the climber and the acceptance. A backwall of the best planes and saws money can buy and all lined up like a cook's kitchen is usually just an image. This isn't really very qualifying but I understand that for some, appearances are everything. Dismantling our need for acceptance is not the easiest of things to do. School (both Private and State) trained us by systems of merit. Ticks on pages and gold stars, straight A's and such all fed our senses by our being in some way approved. This then feeds the need to be accepted by others approving us to fit into their world when really, just becoming an artisan needs no approval by peers to elevate us. That said, every woodworking association seems to work on that basis rather than the freedom of being, well, just ordinary real. We create systems by which merit is given and yet hundreds of thousands of woodworkers in centuries past went through life just making but they made in anonymity and were simply respected by those they worked with. These people were just real. They weren't searching for or needing approval because the work they accomplished in the day-to-day itself approved them. It attested to their ability and stood testament to it at the close of day. there was no parading of expensive hand tools or a workshop so pristine it looked like a premium kitchen in an expensive home. This kind of imagery seems more to undermine what we strive for.

In my world now teaching the more I look back on the ordinary people I taught woodworking to. A 30-day class took students, most with almost zero experience of hand tool working, to conclude serious projects including a tool chest, a coffee table and a rocking chair (as above). Most students were just real and down-to-earth people. Postal workers and clinicians, a dentist and an artist, people working at life. Parents, mums and dads, woodworking teachers and such. The level of achievement was high. High enough for me to say what they made could have been sold as professional work had they wanted to. Of course, they didn't. They wanted the skills more than the pieces they made. It was nice. really nice. Unpretentious. No false claims. Transparent openness.

Comments ()