Plane Away

I think planing wood is quite a troublesome and complex aspect of our working of wood but the good thing is that for every fibre-tearing, grain-ripping stroke of negative pain there are a hundred and many more really good ones. One thing that's certain is the unpredictability of wood when it comes to planing with bench planes. Most planing is used always to smooth and level wood for one reason or another alone. To get good results can never be absolutely guaranteed but to get the best we can surrounds three key issues at least. The problem surrounding planing is not necessarily the tool itself and neither is it always the user but of course, it can be one or both and then, too, both. Persevering in the gaining of skilled planecraft is not an hour's practice or a month's or even a year's. The reason for this long-term learning curve rests not in the tool nor in the user but in the wood itself. When I started out in woodworking as a boy I simplistically thought of wood in the very, very narrowest of ways––trees chopped down and slabbed gave us planks, boards and beams and they could be from any species, were always sawable, planeable, jointable, workable in different ways and wood was predictable for the making of different anythings and all you needed was a pair of strong hands and arms to deliver energy and direction to hand tools to work it. As I say, simplistic. But that was actually all it took for me to believe working it with good results could happen for me. My woodwork teacher provided two woods that could indeed be readily worked with basic hand tools and that gave me the belief that all woods could be worked and worked easily. Of course, long term, that was naive. It wasn't too long before I encountered grain and wood that would occasionally drive me crazy. Even so, those two woods, obeche and sapele, gave me the start I needed with a positive outcome.

When I started my apprenticeship, new woods came my way and one by one my relational (related to by the working of them) knowledge of wood and each wood type increased. The list of woods I've worked since then and now, after almost six decades in the daily working them, is quite vast. Some came and went according to commercial forestry production, processing and distribution whereas others became protected species withdrawn because of overuse and careless deforestation. I am conscious of privilege the past gave me in knowing woods that would and could and should never be used today. Our European softwoods and hardwoods have a uniqueness to them according to the various climes of Europe. I can compare such to those woods I worked native to North America as in Mexico, the USA and Canada. Such diversity. Mixed into such regions are the commonly grown and used Asian wood too. Knot-free, straight grained medium density with stability and minus annular rings or any noticeable growth cycle usually resulted woods that were easier to work. Such woods can still be had from upcycled or recycled furniture and so on. Planing and scraping such woods give tremendous insight into the characteristics of wood types that cannot be read up on or described beyond the very basics of colour, grain type, density, workability and such.

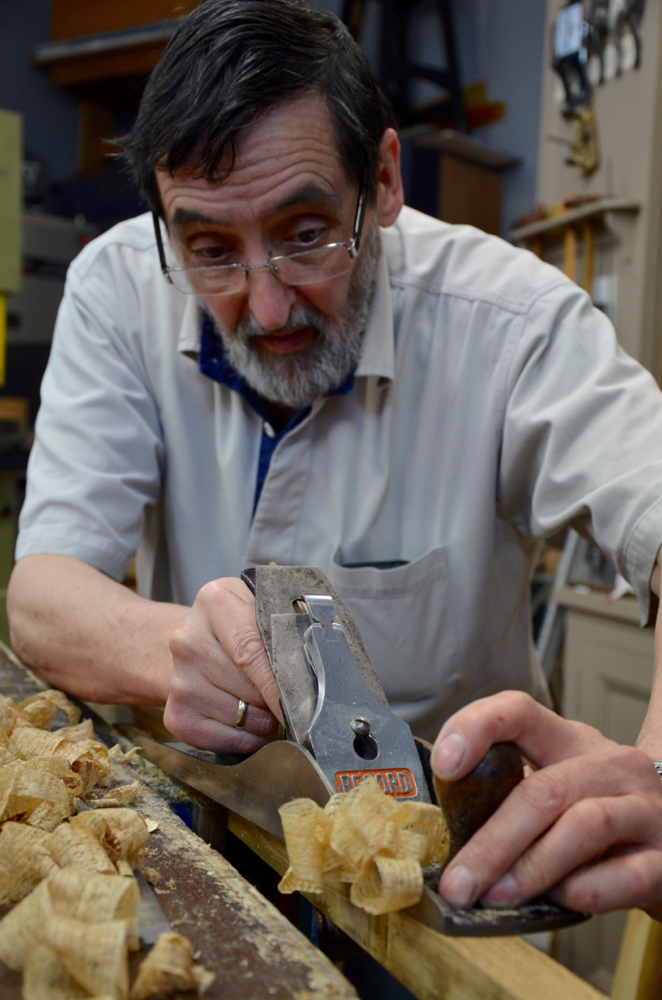

Experience tells me that most woodworkers starting out give up and give in far too quickly and readily after a few miss-jumps even at the shallowest of hurdles. That rider's hesitation is sensed by the horse even though with the right measure of rider confidence urging the horse on the horse would have taken the jump easily willingly and with an unfaltering leap. But I understand that leap can be intimidating when all you have known is a ruined surface uncorrectable by a novice starting out. There again, I have known many an experienced wood machinist who never mastered the hand plane resorting always to using only some kind of power sander. But in mastering the bench plane the incredible happens and it is not just about merely sanding a surface smooth. In woodworking, the plane can never be truly replaced and most sanding becomes necessary where skill in using hand planes is abandoned and the planes remain untamed. Planes have a much wider capability of multiple tasks than merely smoothing wood. In the hands of those who mastered them, you can take off fractions of an inch in thousandths if you want to and this comes with a single and continuous cut as a ribbon as opposed to a million chips leaving some measure of ripple texturing the wood's surface that then needs successive work with sandpaper. Hand planes handle well are about as perfect for getting a door in perfect synchrony with its frame or the drawer to close after a little swelling. This tool leaves the surface pristinely smooth and within a thousandth of an intended goal.

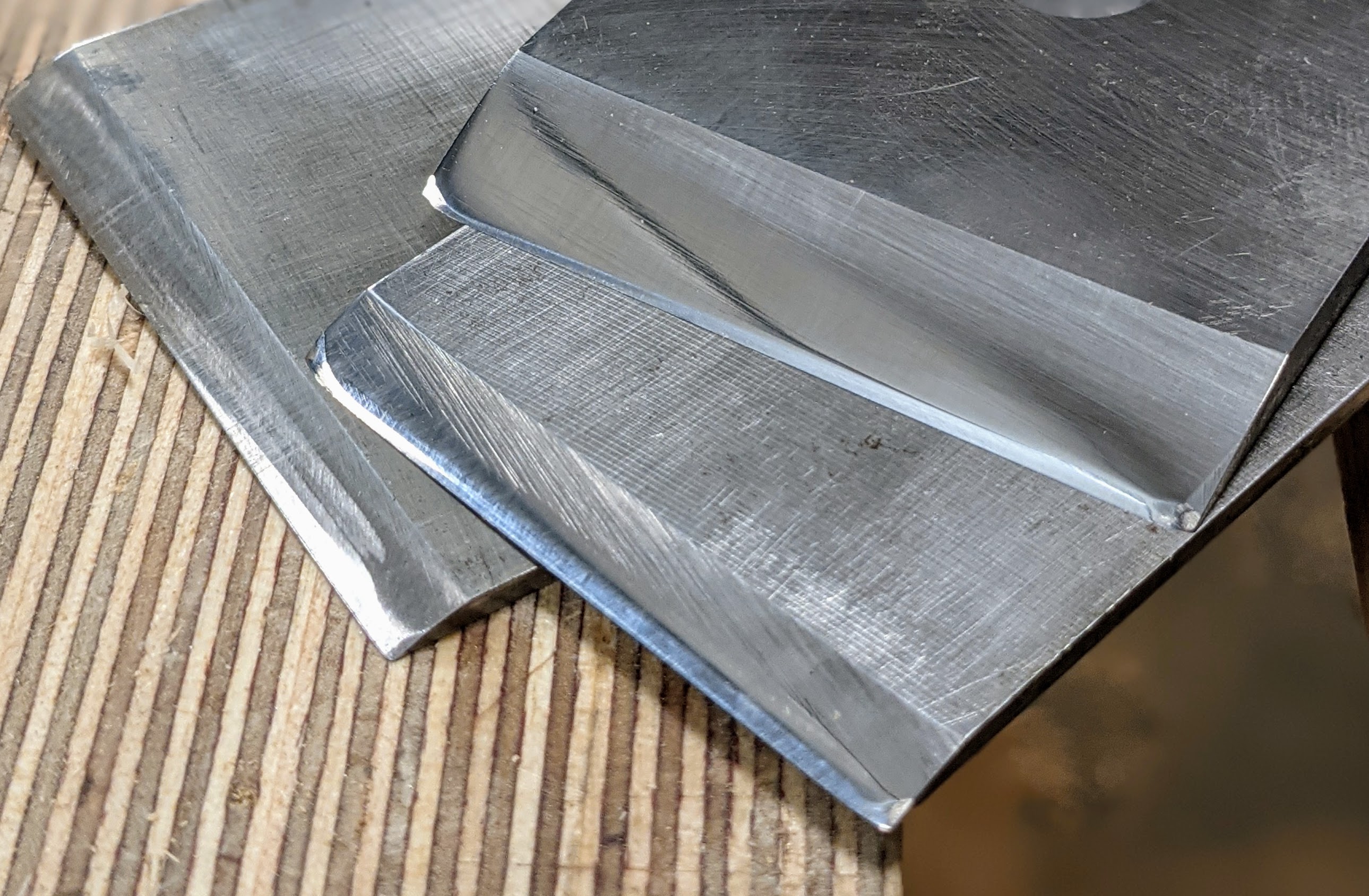

The ingredients to successful planing are in the setting of the plane's cutting iron for depth of cut along with its parallelity to the sole and, equally important, that sharpness defining the mirror-smooth surface we strive always for. You also need to understand the adjustment systems that develop these elements so that you know how much to turn that depth adjuster and the lateral alignment lever. The turns on the wheel are never two the same. Yes, we would like a dial-in a number for each par-turn but there is no such thing as some woods will take a mildly heavier cut and others will send that silent scream as the wood rips and tears from its root. This does take time to master if mastery is indeed what it's called, but you can do as millions of hand-tool woodworkers have in every woodworking trade across the world have done for three or more centuries prior to machine working of wood and that is to master it to the best of your ability.

What is actually more important is that you realise it's more likely to be the wood than the tool used that has the problem. No two wood types are the same and two sections from the same board side by side and one under or over the other are as likely to be unalike as can be. Some woods tolerate of bad workmanship and inexperience whilst others absolutely demand the highest levels of experience and skill. Planing a surface in ten strokes can create the nearest thing to perfection you can ever get and then that eleventh thought-you-needed-it stroke over the same successive patch rips the root of the fibres to render beneath the wood totally unfixable. But eventually, you will sense the surface before the stroke takes full sway and in a split-second twist or turn you'll save the day.

Nature, by its very nature, is almost totally unpredictable and most often we must constrain it by some kind of sterilising solution that renders nature itself sterile. Modifying plants for maximised growth, size, type and so on may give us uniformity but almost always at the sacrifice of something else. With the reproductive systems compromised, we must keep going back to the modifying source of copyright. In our kind of woodworking, it is the free spirit of working real wood that creates the uniqueness in the final look of what we make. Equally important to us is the how of it. Mass-made plywood, fibre-boards and particle boards, naked or faced, look like unreal wood though even plastic surfaces can indeed deceive us at first glance. Mostly, and of course, MDF has replaced wood because of industry's need for total predictability and control. Created for economic large surface area materials, the material must comply with the intolerances of machines. You cannot have sheet goods that expand and contract at the same rate that wood does. Feeding wood through protracted periods of processing might mean a material can expand or contract enough to jam in the machine. Our working with human flex enables us to bend and yield here and there to absorb small changes.

So here we are. Planing wood needs to be predictable as much as possible. My planing wood in my working is as real as I can make it. In filming, the wood I use has awkward grain and I do not suddenly run to machines like a power planer or a belt sander to take out difficult defects because handwork is too awkward or complicated. What you see is what you get and what you see is always real. On the other hand, it is too easy to believe some YouTubers presenting the plane flawlessly and creating equally flawless surfaces. 99% of this type of presentation is disingenuous at best because anyone should be able to set the stage for a positive outcome if and when they take half an hour for sharpening followed by a few steps in levelling the wood and readying the plane for a staged performance videoing. The three subsequent shavings are bound to look just brilliant. There is a reason they rarely if ever take the wood from rough-sawn to trued in successive work. The same is true when the wood is a flawless piece of hardwood like cherry, maple or oak. These woods are some of the easiest of all to work no matter the task and always guarantee a good outcome.

Although I don't watch video presentations by others (never found any need to) nor like to either, I do know how the actors work on every platform. Placing a perfect piece of wood in a vise to swipe off successive onion-skin shavings that wrap around the wrist like gossamer is not really of any real help to anyone. Planing wood like this is a very different animal than wood still rough-sawn, crowned, bowed and twisted. My planing is usually in the saddle actually making for a series I am building. It's always on the surface of the wood I am actually using in the actual project I am making as a whole for the audience be that 8" wide or a thin edge, the intersection of a jointed area or the trimming of something like a door or a dovetailed drawer with six dovetails. I think my audience appreciates that I am not selling planes or blades, guides and equipment. Again, what you see is what you get. I simply want people to believe that woodworking did not come naturally to me but I naturally loved it enough to overcome my doubts to gain mastery over a number of years. Most of the demonstrators taking a pristine piece of wood locked in the vise to take off onion skin shavings a thousandth of an inch thick are not showing the reality of life but a very carefully orchestrated end result usually to sell something. It looks impressive, always looks impressive, but is always completely unreal and that's because it is artificially massaged to that end.

Avoiding any spin, it's in the spin, twist and flex of our planing that we gain long term mastery of hand planes and we never stop learning to deal with grain that would otherwise rip. We must sensitise ourselves to swivel but we must approach wood with the reality that as it is with real life, wood comes with knots in it. And what we see in the surface of a knot might not be visible on the opposite side of the board or beam. This inevitably results is some level of tearing so our anticipating problems ahead of sticking out is key to avoiding deep tissue ripping.

Comments ()