Plane-ability

Until you do it you won't understand and it won't be because you don't want to understand or even accept it, it's because you simply can't. It's not unlike using a chisel sharpened to say 250-grit for years on the old India Stones and then being given a chisel sharpened through a series of abrasives like diamonds (my very favourites) and on up to buffing compound at around 12,000-15,000. One takes a hundred times more effort to cut the wood and that lack of true sharpness is then reflected in the surface you just cut into. Your first thought could be a full rejection of what's being told to you. But then when you actually feel the difference as you push the tool into the wood followed by seeing the outcome––you become a believer. But, sometimes, fairly often, I do sharpen to that lesser level and it's not because of laziness or procrastination, I did it just yesterday; 250-grit and back to scrubbing off excesses before sharpening to finer levels for the final surface finish is something I do. But I'm not talking about sharpness here: the plane options as in choosing all metal over wooden ones, might be dismissed because one is 'old' technology and therefore considered out of date or outdated. We might think something to be more archaic than in any way useful to us when the alternative could offer us truly viable options for improved performance, easier working and much more. I want to talk a little about how planes will feel different and how if we went back in time a hundred years and more, we would better understand why crafting artisans in woodworking were indeed so very stubborn about keeping their wooden planes instead of accepting the more modern versions in cast metal. Certainly, there were metal planes available and craftsmen liked them well enough to use them for decades as is evidenced by the patina on them. I would like to change the word 'stubborn' to 'determined'. Old craftsman woodworkers were determined not to give up something that was better for something they considered less comfortable for them to work with. If you, like most, consider people who won't give up working with wooden planes, and we are talking about a lot of modern-day users here, you might do so for the wrong reasons. Wooden planes are far from inferior and might well still be superior though you will be hard to convert if you have never mastered the use of one. This is usually the point when terms like Luddite are applied to people supposedly rejecting new technologies when it is actually done to deprive people of true realities. Here's an example: "Our thicker irons eliminate chatter!" when the thinner irons never chattered in the first place.

Experience tells me different things. Mostly I believe that it is not necessarily an either-or and that we might enjoy the benefits of finding space in our work for both and all. Do modern planes of the all-metal kind keep their edges better, feel easier on the wood and in the hand? Well, that depends on a few things not the least of which is our attitude. Are we receptive to some old and ancient things like tools, technologies, techniques and methods being as good as if not better than new, for instance? Or are we simply dismissive? Of course, that works in reverse too. We can reject the new because we are, well, just set in our ways. But many times when people were reluctant to change it wasn't a rejection of something new so much as shifts that altered a way of life. Here is an example to chew on: The mass production of growing raw materials demands a means to produce fabrics faster and more cheaply. This led to our discarding of good clothing before it was worn out and then slave labour to produce such things. I know, it's a bit simplistic. Or is it? Look at all of the now so-called global issues surrounding just the one pair of jeans you are wearing.

Experience in using both wooden and all-metal planes over extended periods is likely to reeducate us if indeed we just give it the time it takes to adopt, understand them and get used to using them. That can be expensive in time, money and owning the tools to practice with.

My wooden versions feel wonderful to use and especially is that so on some particular woods. Ninety-nine point nine per cent of British-made wooden planes are made from solid, air-dried beech and of course, air-drying gave the most stable beech wood for planes. vastly superior to kiln dried wood every time. Beech of the vintage kind is amazingly resilient to wear, has tight interlocking grain and is extremely stable.

The British wooden planes I currently own all have laminated steel cutting irons that have good edge retention and take a keen edge too. Just as good and equal to any modern versions I have ever used. I think that this might well be because they were hammer-forged under the heavy tonnage of trip hammers rather than just rolled steel. I might dare to suggest that they are at the very least equal to any named cutting iron you care to name including those made by the so-called premium plane makers and they keep going over an extended period. The Mathieson one I am using above and my Marples ones all just keep going. Aside from that though, those who do believe we've truly bettered the bench planes with all metal ones usually say such things in ignorance rather than experientially. Even though it is slightly possible that they used a half-decent wooden one it's most likely that they never put enough into it to match their skill levels to the masters that owned and used the wooden planes. Gaining mastery in using any hand plane as the ancients in our craft did takes time and most people these days are time-poor so I understand the reticence to try something just for the sake of it. You don't just pick up a wooden, UK-designed 18th-century beech plane after relying on all-metal ones and own the experience. These old masters truly mastered the working of them. They sharpened and reset them with incredible speed, using the bench itself to nudge the cutting iron in and out for depth of cut and then tapping the plane or iron for sideways for lateral alignment in split seconds as they went on with their planing tasks. No matter how good you are with an all-metal version, mastering wooden ones of the British type (which includes those in the US with a few slight modifications) takes time but once you have it the methods belong to you and so too the joys of using them. Woodworkers may be free to give a negative opinion on using wooden planes as some kind of entitlement but it's really only worth anything if indeed it is based on fact.

If you have never mastered handling the large wooden bench planes preferred by all British woodworkers for two centuries then you are unlikely to understand them as fully as they need to be to work them well. That being so, I understand the belief that in the plane's evolutionary process, things can only be bettered. The reality says differently. Also, you cannot, cannot master the use of them in a matter of a single try so a true comparison would only be valid if you have invested yourself to some level of acceptable mastery in real-life working day in day out; something most could never do because of time or a lack of interest. You must have mastered setting and adjusting them to a high level of truly efficient mastery. It's very doubtful that you will know such a one if you live in countries that used British-type bench planes that had much greater bulk than other European and Asian wooden bench planes.

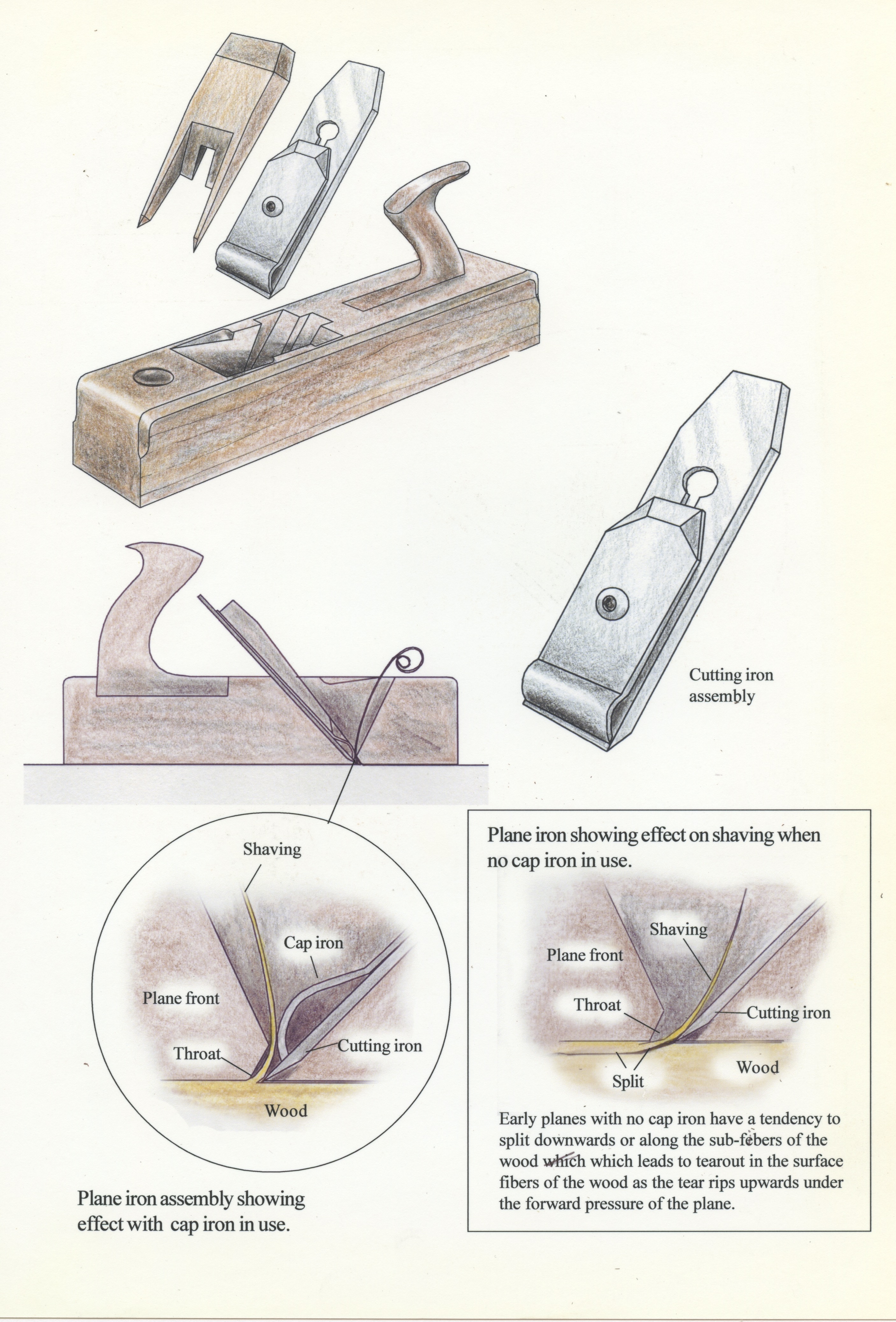

This is my best offering of the difference. Wooden scrub planes had no such name and neither were they created as such but the action of "scrubbing off" was so named as the act and art of using one. Well-worn short-soled planes continued in use after the soles were worn down half an inch in height and therefore had a wider and more open mouth or throat which meant that surfaces left after the planing were less refined or even somewhat torn. That increased gap allowed the wood to rise into the through before it was cut and parted away by the cutting edge hence the tearing or ripping of the shaving from the main body of wood. In scrub planes, the user cambered or rounded irons which made the planes easier in the cut. This left gentle undulations along the planed surfaces. You will often see this as a finished level of planing on unseen surfaces like the undersides of drawer bottoms and the back panels of case pieces, tabletops and so on. This was perfectly acceptable in vintage woodwork where the economy of time was more critical; passing wood through a power planer or a drum sander takes but a minute compared to half an hour with a bench plane. These planes started out with mouth openings of between 1/32" to 1/16" between the cutting edge and the fore part of the plane sole. After a few short decades of use, the plane's sole wore down causing the gap in the mouth opening to increase. Reaching an opening of 1/4" to 3/8", you see above how this then allowed for thick shavings to pass through the mouth in quick succession. Though these planes still took decent shavings, they were usually repurposed for roughing (scrubbing) off and roughing down, which they did more capably and more rapidly than any all-metal woodworking plane designed to that end can. The shortness of sole enabled intense localised planing work which relied on the crafting artisan's skill and ability to work the surface as level as possible by eye alone but in preparation for subsequent planing with longer planes like Jack and Try planes.

Jack planes also wore down in somewhat equal measure to the shorter smoothing plane cousins through continuous and consistent work. The mouths of any well-worn planes often had patched-in sections with a recessed piece of hardwood to close off the throat again. This extended the life of a highly valued tool for a few more years. Of course, the plane soles continued to wear away stroke on stroke and over the decades, depending on use, became too worn to use as truing planes so these too became longer roughing down (scrub version) planes with the more open throat allowing for deep cuts and hogging off of masses of thick shavings at speed. In wood, the planes never felt crude, cumbersome or awkward, which might seem surprising. In use, on wood, whether as a scrub plane or a fine refining surface plane, the wooden planes glide supremely. Think cruise liner on still waters coming into harbour here.

The longer Try planes wore down much less than the short-soled smoothing or Jack plane versions simply because the early use of these two starter planes reduced the impact on long planes. That said, in the hands of a skilled woodworker, the try planes are actually minimally needed if at all. I rely on Jack planes for 95% of my truing longer work anyway, even for long edges. Though all of the wooden planes might seem or feel heavy and unwieldy in the hand and arm, you soon get used to them and in most cases, a wooden Jack plane is about 20% lighter in weight than the standard Syanley versions and almost 50% lighter than the premium heavyweights makers seem more wont to make. Persevere if you are indeed new to them; on the wood, they respond very differently and once mastered they are very enjoyable to use. No matter the wood type or the state of the surface, on the wood they suddenly feel utterly lightweight, almost as if they are not there. This might seem an exaggeration but I assure you it's not. Wood on wood in planing mode, you will be stunned by how easily it glides over the surface. What slows it down to sluggish levels, as with all planes, is a dull cutting iron and too deep a cut. Being pushed over the surface of some softer-grained woods, pine, fir, poplar soft maple and many hardwoods with softer grain too, this plane can hardly be felt despite the fact that wooden planes of such mass compare very closely to their all-metal counterparts of the 19th and 20th centuries in weight. Even waxing or oiling the soles of metal planes will in no way be comparable to wood on wood. They may be similar in weight, but on the wood somehow all of that weight on wooden planes just disappeared. Not so with metal planes and that's what makes the difference.

Be careful about workbench heights. The heights of workbenches some people might consider more practical and standard at lower levels might well be more tosh than practical for we hand toolists creating joints, planing and sawing wood and all of the other elements of hand tool work. And if indeed you are not using hand tools then what might seem logical can indeed be highly illogical. Telling you you need to place your upper body over the plane and the planing work to make the plane work is not really helpful. What would likely be more helpful would be to say you need to keep up with your plane sharpening and that alone will do far more to pull the plane to the work than having to increase unnecessary pressure and friction to the wood to smooth and level your wood. Ninety-five per cent of poor planing results come from procrastination in sharpening the plane. I am likely to sharpen any plane four or five times per hour of plane work at least.

Wherever and whenever possible, a bench height needs to be custom fitted to the individual first and then too to the type of work they might be more involved in. My work is a combination of surface planing, sawing and joinery of all types along with assembling the units. As Mr average height of 5' 10 1/2" (1.8m) the work I do is consistent. My bench height has been 38" for almost six decades. I have never had back issues and still, at age almost 73 nearing 74, I have no aches in my body anywhere. A machinist on the other hand is more likely to be assembling components made by the machine so, yes, as more of an assembly bench not used or much needed for hand tool work they might need a lower work height than a hand tool workbench.

Sometimes, often, we can assume that we are further along a pathway than we actually are. That somehow we put some distance between the old and the new and the new is always better. We might even speak from this supposed vantage point yet be quite wrong. If we skip a generation or two of the ancient makers and users and then the not-so-ancient in anything, we will naturally assume something better came along. And then books get written too stating this or that and before we know it the assumption of being right becomes the fact. We then quote the fact and the quote becomes well-known and, well, right. I can think of a dozen examples and have tried to remedy the untruths of things as they came up. I actually wrote 'think' in place of assume in that first sentence of this paragraph and changed it to assume because it's doubtful people will actually even think or give a second thought to it. I think this to be an important point.

As an afterthought, the average Britain in the 1700s was supposedly three inches less in height than today. A lower bench height of 34-35" would have better-suited workers of that day. This video will help you to understand the synchrony between planing and bench heights.

There have been pivotal points in my life where I have experienced a feeling even though nothing touched me and I touched nothing. I recall the day I first queried what was being said online and in magazines about things and realised that what was said was completely erroneous yet was so very instant. Take BedRock planes, as an instance, or workbench heights needing to be ultra-low for planing and such. What about laying planes on their sides or Japanese saws being better than Western saws? All just more tosh. You can make anything work and make anything you say fact if it just suits you. The BedRock frog supposedly being vastly superior to the Bailey-pattern frog in Stanley planes is as good an example as any: it is decidedly untrue. My experience told me something completely different and for many good reasons. I knew the truth of it because I never reached for any of these so-called "Superior" or "Premium" planes even though I owned several of them. Back twelve or so years ago I spoke of the superior qualities of the better steels used and also the more advanced engineering, the crisp bevels to every corner and the flawless uptake of the screw threads and such. Since then I have changed my mind. I have found that I sharpen brittle steels more frequently and with more difficulty but not because they dull so much but that they seem more apt to edge fracture when I use them in the reality of planing woods with the occasional hard knots like you get in most woods in the day to day. I very much prefer that small degree of flex and tolerance I get from the older lesser planes too; a bit more give and take perhaps.

I have personally found my owning several of these more modern planes with tight tolerances is of little if any advantage. In fact, dare I say, of no real advantage at all. Once aligned and arrayed there on the shelf alongside my very basic, non-retrofitted Stanley #4 versions with their original cutting irons, I found myself never reaching for the premium versions again but always reaching for my Stanleys or, secondly, my Records. I am still on the first-ever plane I bought in '65 and I'm on my fifth cutting iron. Why did I no longer ever reach for the Lie Nielsen, Clifton, Juuma, Quang Sheng, Woodriver or whatever other knock-off version smoothing plane for my daily use? Why are they now stored in plastic boxes and why am I currently considering a garage sale of all of my excesses to include these as being for sale sooner rather than later? Well, I just changed to using the 'the' before each one of them from 'my' to 'the' because they never actually felt as though they were as much a 'belonging mine' as they were the makers. My Stanley (along with others) became mine through the adopting of them through weeks, months and decades of using them. It didn't happen overnight it took five years before I truly owned my first Stanley #4 smoothing plane from the 1960s. And then I owned three of them even more a few short years back when I replaced the handles with those I made from Yew.

I conclude now that my adopting and enjoyment of using and advocating the British-type wooden bench planes have absolutely nothing to do with nostalgia or antiquity, a stubborn refusal to go with the times or any such thing. It has to do purely with functionality. I think if I put one of my wooden planes in your hands and set you up at my bench you would see exactly what I mean. Once you understand how to adjust them, the speed in experienced hands equals that of those with the adjustment mechanisms on any of the modern metal-cast planes. The men I worked with as an apprentice adjusted their planes after sharpening in a matter of seconds. During use, they could bump the heel of the plane to withdraw the cutting iron by a thousandth or bump the toe to reset it by the same thou' of an inch and get on with the job of planing. This was done on the end of the bench or the side of the vise. I know, we dismiss them because this sounds, well, too crude. But you must remember these planes survived through a 200-year span of woodworking history and more, a period when some of the finest and most creative woodworking of any kind existed. Infil planes with cast metal soles and sides came into being but were less used by most woodworkers than the all-wood versions because of weight, cost, high friction and so on. They never went longer than a Jack plane because the weight would have been impossible for most men. That too tells you something. Also, it's well worth remembering that all metal planes distort in exchanges of temperature. Rarely do they remain true and flat and straight.

Furniture makers and joiners bought the castings alone and made their own infil for the plane totes and infil areas from scraps of hardwood be that oak, rosewood, ebony or fruitwoods like apple and pear. Even so, these planes still stuck like glue to the surface of wood being planed and really did need a wax candle applied to the sole to allow them a freer passage. Other infil planes were professionally 'stuffed' and many makers came into being to supply a ready-made, ready-to-go version. Norris was one of the most popular makers and these planes had full adjustment mechanisms that set the depth of cut along with an alignment lever, often all in one, to ensure the blade had parallelity with the plane's sole and depth of cut adjustability.

The wooden planes were the ones 99% of woodworking craftsmen could reach for. And neither should we forget that it took almost 60 years for Stanley to finally succeed in getting woodworkers to adopt the all-metal Stanley ones. Stanley couldn't persuade the artisans to make the change, they just never did get them to change: they simply died off over a six-decade period of transitioning when hand planing anything was being taken over by more efficient machining and so was dying off at a rapid rate too. Machines were taking over woodworking at an alarming speed and the wooden planes became obsolete because the makers were dying off and such tools were needed less and less. They were never abandoned because they didn't work and work exceptionally well but because they didn't keep pace with mass manufacturing and they were needed less and less, as were skilled artisans too.

So what is it with those of us still clinging to the hand tools and the methods of using them? Why not just get access somehow to machines? For me, this is where the rubber hits the road. Someone commented recently that most of my viewers relied on hand tools and that it made no sense to rip-cut thick oak using a handsaw. It was of course a strawman baited with hooks simply because no one has ever said to do so in my blogs or social media. I ripcut and crosscut oak and other hardwoods and softwoods every day and I do so using both hand tools and a medium-sized 16" bandsaw. I am an advocate of bandsaws because these machines take such a small footprint and they are for me the most versatile of saws used for ripcutting wood. My garage workshop only has about three square metres of free workshop open space for me to work in. One tablesaw or planer would take up all of my space if I introduced one for me to use. But even that is not a good reason not to own one. No, not at all. I simply like hand tool woodworking for a series of really good and justifiable reasons more than owning a mere convenience. I need to give no account to anyone for my preferences.

Sometimes, and you might need to think about this –– consider it. In my world, for a lifetime of daily, all-day making week-on-week and year-on-year, woodworking has had perhaps a different and dare I say more profound realness to it as a class of working manually. Looking at it from this background will automatically translate things differently in that I am not from an academic place nor a desk job. I never attended university and college was something of a more sad joke. Most of my progressive education came at the workbench with a man named George who took me under his wing to teach and train me. When I began here in England, we that did such work, wearing overalls or aprons, boots to work in and with our hands for a living, would be regarded as something called, well, working class, manual labourers rather than as pastimers, amateurs, hobbyists and such. Of course, our modern-day versions would never use such terms and they no longer look as we did, they dress differently and approach work differently too. Today's such versions are Influencers, Bloggers, Vloggers, Instagramers and so much more but perhaps less too. There is nothing so, well, ordinary about makers of this upper echelon. That I have wanted to persuade others to adopt elements of it where possible changed my way of seeing my worklife. I express what I know as truthfully as possible. I want to give everything without dragging things out. I recall a conversation with the then Fine Woodworking editor (USA woodworking mag) who wanted me to write for them. In the conversation, he said, "No. We don't want whole articles. We want to keep our subscribers coming back. Make them short, in parts." Naah! I thought. So I never did write for them or any other mag after that. Some woodworkers express things from their own background not as makers as such but as online presenters. By 'as makers' I don't mean they don't make but that they make on a more limited basis and purely to gain followers and subscribers. They never made to sell their work for a living as an employee full time or a self-employed maker selling their work to the public. This makes a big difference to both those watching and then too in their presenting. It's just different. Hence the gladiator poses holding power routers and skilsaws. Dramatic posturing and a catchphrase strapped across the keyframe. Not too real.

I have seen how entities in woodworking promotional venues achieve different things. The tablesaw blade salesman takes a bar of soap to the saw blade before demos and after the cut hands over the offcut and the feel is silky smooth. Some in the areas I am more involved with spend quite some time tweaking their premium planes for optimal performance every twenty minutes so when a potential customer tries it out on some curly maple it cannot fail to impress. Of course, curly maple is a very nice wood to hand plane. This is all reasonable. The cutting edge and blade alignment, depth of cut, etc make a huge difference to trialing a plane. Obviously, spending time sharpening a cutting edge, perhaps as long as 10-20 minutes, gives the plane the edge it needs but in my world, it is just a bit unreal somehow. As a maker, I just sharpen in a minute or two, reload and get back to work. In my world, their world would be a luxury and would never be very practical, no way. And perhaps this is why so many full-time woodworkers working with machines say you can in no way make a living using hand tools (My previous article I just finalised and posted shows something very different). Anyway, having then loaded the cutting iron assembly, taking a similarly long period and setting everything before they present the plane to a pristine, straight and trued-up piece of hardwood that's straight-grained and knot-free, they whisk off "onion-skin shavings." as though this is the goal of planing wood. Maple, cherry, oak, ash, beech and a few others would all be good examples of wood too. Bracing themselves heavily they then lean into the already planed piece of wood 18" long and a full-width onion skin shaving ripples from the plane. As the plane emits the shaving they stretch it part way through the stroke as the work is concluded. This act alone is completely unnatural but it's done with a purpose in mind. It looks very controlled, easy. This is how you sell planes, cutting irons, sharpening stones, honing fluids, workshop classes, workbenches, vises, bench dogging systems, clamps and much more. The observer, never experiencing such magnetising results is immediately mesmerised by the desire they have to achieve this kind of result from a bench plane. Whatever is for sale in that particular place or at that time is the magic bullet needed to make a sale and make you the better woodworker. The promises are in the instance of success. It's not unlike the promise of instant weight loss from this or that diet, really.

The problem, of course, is that we are new to woodworking with hand tools. We rarely have pristine wood, the perfected sharpening, any experience and so on. It's more likely that we actually have sections of wood that in some way form a kind of frame, perhaps a box or other such sub-unit that has contrary intersections of wood in slightly different levels that defy uni-directional planing. And then too we have grain that's totally contrary and no matter which way the plane is pointed it's often or even always against the grain. So why am I saying all of this? Well, sensationalism sells as do smart-alecky postures and sayings. These mostly substitute for the reality that real woodworking mastery is totally interesting in and of itself. It does not need hype and hyperbole to make it work. The attention-grabbing has proliferated with partial strap lines with hooks to them. Few sites are free from promotions, sponsorships, free products and so on given to the various platforms to work as sales pitches somewhere in the deal. I want my work to be real, honest and uncompromised.

Comments ()