Where Freedom Thrives Most . . .

. . . is in the lives of its maker hosts!

Things changed with COVID. Life. No masks now, freedoms back, but something did shift in every culture like a swelling sea that never settled back to the same levels past. We lived through extreme extremes of different kinds with effects that affected all people differently. Some of us got COVID with dire consequences while some just skated through it with nothing more than its distraction. Ukrania stands between Russian aggression and the rest of the so-called free world and the extremes as with any war are felt on a global scale. We cannot ignore such impacts in physical or spiritual realms. We can only take control as much as possible within the sphere of our own limitations. Within my own sphere, I am glad that we have ably continued our outreach quest to reach and teach real woodworking. Here, we work soberly and solidly to bring sanity beyond the insaneness of brutality by simply training woodworkers everywhere we can. Our expansion continues, albeit slowly and perhaps a little less interestingly without the razmataz, but it's less about numbers than it is about truth. Often, as happened this morning even, someone will say something like, "I cheated and used my tablesaw. . . " to do this or that ". . . because it was quicker and easier.", not realising it wasn't quicker nor easier, it was that he always chose what he saw as the easy route because he never developed real skillfulness with hand work. My week, as yours, has just begun. I have wood stood by the end of my workbench acclimating together with plans roughed out for the bed I started making this week. Oak's own characteristic aroma is given off with each cut I make and the shop fills with a scent that ebbs and flows in the atmospheric swelling. When I arrived yesterday the scent wasn't so powerful as when moisture is given off, but cutting into it was just enough to translate me back to the days when such kiln-dried wood became a thousand walking canes and by the end of the month UPS picked up my boxes from the workshop to deliver them all over the USA.

Designing and making are two equal parts -- two halves of the same coin -- and, though opposite sides, they interplay conspicuously throughout a given day of flipping to make. Though common enough for me as a designer and maker, I see it as no ordinary thing. Hyphenating designer and maker doesn't make it a single entity but two distinct elements of a maker-designer's life. Scraps of paper often carry the lines of an idea be that by drawings, sketches or words, through these things something emerges as if from nowhere to encapsulate the ideas more solidly. The overall concept always comes together just fine but then the joints need formulating and decisions of engineering must be thought through and considered more deeply long before you get too much made.

Hannah comes in in the midst of things, always pops her head around the door, says, "Hi, Paul!" and skirts through to her bench where her tools and wood wait and in minutes she's making. She's self-motivated and direct. You sense her excitedness through her movements even if she's in a different space and I only hear it as she lifts each tool to work. This lived inspiration is more viscerally discerned in the presence of some people. John is just the same. Inspiration never grows old, never tires, is never outdated and the logs in the fire of creativity spark off the creatives to ignite one another throughout the day.

Hannah's been busy these past weeks making small things to sell at craft venues and has done well. Selling things you made from scraps and boards rough-sawn translates into income, yes, but more than that, for young makers it validates you as creative enough and sufficiently skilled to make your living from it. What's all the more valuable is that this was all made by hand and not machine. What's the difference? Well, if you have to ask there is no point my really explaining. There was amazing skill and dexterity in what she did. Use your imagination. It's rough-sawn, unsquare, unstraight and she sharpens a plane and saw as needed to make the wood work for her. I know I am preaching to the choir here on my blog but there's a message in it. She's skilled in all spheres hand made and she's selling her work.

Six years or so ago, when Hannah came and had never used a plane and never experienced sharp chisels, she was a maker yet to emerge. She'd never made a dovetail or a mortise and tenon and then, just two years later, she'd made her toolbox at top. All that she had gone through up until then was the foundational woodworking course I put together for people starting out that I still use in all my training and teaching here online and elsewhere She'd made her bench from studs and taken it home to continue working there.

Three years ago Hannah and I found ourselves involved in transferring our skills and knowledge to support workers at a centre for young autistics learning to cope with the adult world. Up until our arrival, machines and a machinist were taking centre stage in teaching and training young autist adult woodworking. This seemed very incongruous to me. The exact opposite to what was needed. It was at this point that Hannah took on the mantle of teacher and she and I began training the support workers to work with hand tools and support their autists in the craft workshops and through them, we reached into lives we might never have reached at the centre. Hannah had a remarkable ability to communicate her skills in a highly relatable way, often without words, and suddenly I saw her as both a skilled maker and teacher. These are the remarkable things that just leave you dumbstruck, asking yourself, "Now where did this come from?"

John has been teaching and making and he too enlivens the shop through interactions of different kinds. In his making, he makes beautiful cajones. These are not the mass-made versions but the hand-made, hand-planed opposites with all the internal surfaces hand-planed and scraped to maximise the crispness of the internal surfaces to give projection and crystalise clarity. These are the ones you can't buy because hand-makers like John rely on planed and not abraded surfaces that tend to dull and muffle the sound. Of course, the interlocking dovetails, all hand cut, 40 of them, exemplify the signature of a master in his craft, but then there are the hidden details you will never see and know of. Makers use thin, three- or five-ply plywood for the tap and percussion panel for strength, but the solid wood panel facing it has an unusual joint around the rim of the Cajon that fits tightly into its groove all around. This allows for any shrinkage that might take place. Without this unique feature, the panel will often split irreparably.

John too is a remarkable maker-cum-teacher. He works with Jack to teach and train alongside me each week but now has begun his own one-day beginner classes here at the workshop. Hard to imagine our first encounter back in 2007 when he came to my home garage to make a workbench as a first project. I had taken a sabbatical from my US work for a year back then and came back to the UK which was good. We've been friends ever since and we bounce ideas off one another constantly in the day-to-day. "Hey, John! Have you ever tried this?"

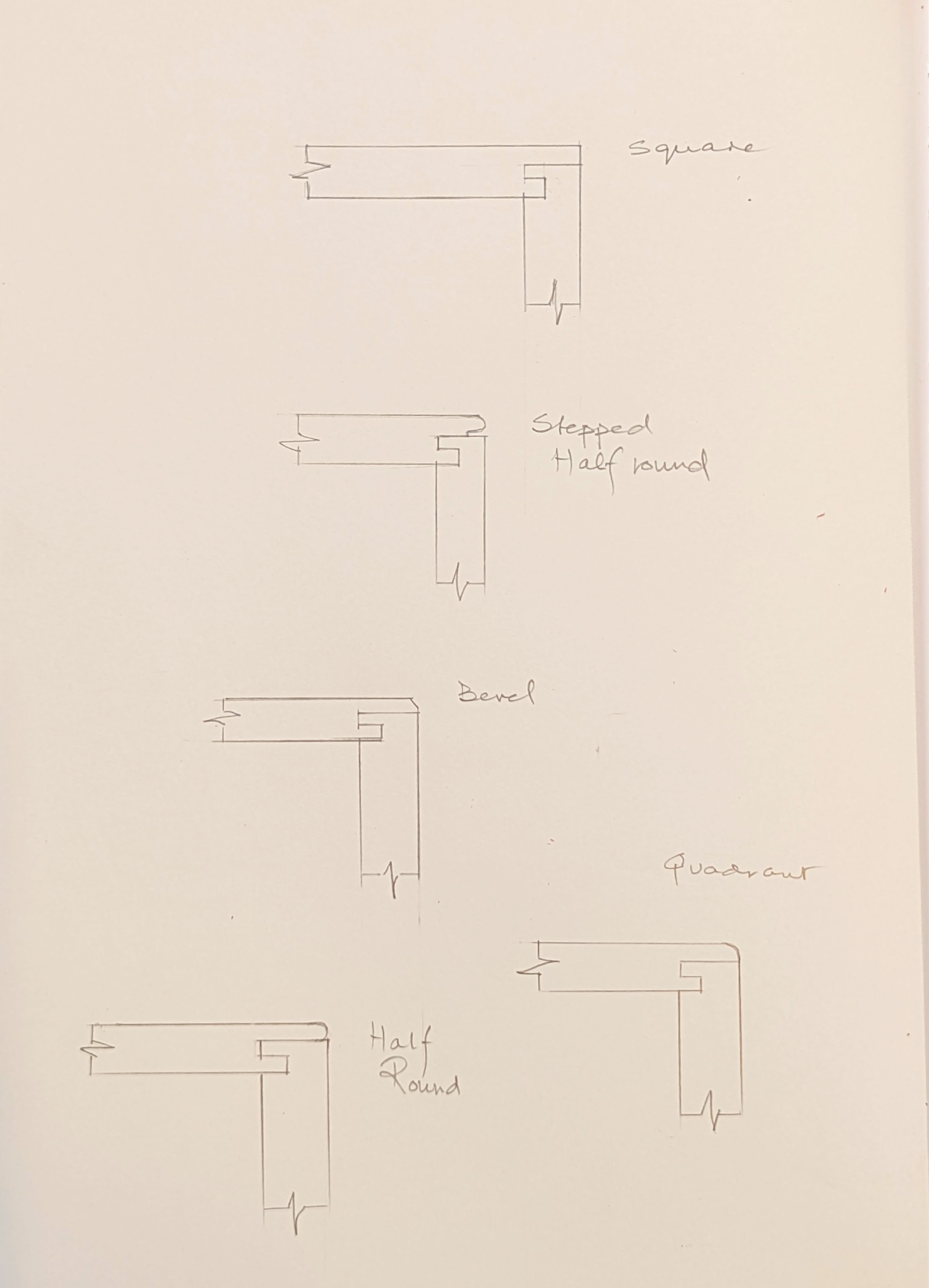

The beat panel made of thin plywood is simply screwed as a very basic panel in place to the sides top and bottom, but the front panel with the hole is let into grooves around the rim. This was a suggestion I made to John as he was building and I suggested it because it was a joint I used when I designed the two credenzas for the White House on some panels I wanted from solid wood. On these pieces, we allowed no engineered boards as is the modern trend for furniture pieces with veneered facades on MDF. Above are some options for the panel corners. There are several more and it is a matter of personal choice. This neat-looking joint always looks good even if shrinkage does take place but if you dry the panel down enough you should have no shrinkage issues occurring anywhere.

Yesterday I began dimensioning my oak for the new bed. It's often assumed that I either buy in my wood ready planed and milled to size or own machines to do that with. I don't. I have no real need for them, though I admit they are much easier when it comes to dimensioning wood. Beyond that though, what about you? Would I be cheating you of realness -- the genuine article, were I to mill all of my stock using machines only and telling you to do it by hand? Of course, I would.

Though I value the hand work mainly for the intrinsic value sentiency brings to my life, I really value the use of it for the higher demand it requires of me in connecting to my work, the wood, the environment I work in and then too the interplay all of the components wrought in realms mostly I see as actually undefined. I think we underestimate the importance of exercise for our physical and mental well-being through interactions handwork demands of us -- something never even approached by machining simply because machines are designed to minimise the need for human input, physical endurance and skill, especially skill. What's the saying? "Use it or lose it!" and, "No pain, no gain!"

I understand that the manual-type work of which I speak can be painful for those with diseases, diseases such as arthritis, multiple sclerosis and then many other disabilities too, and it is better to use machines if the disease would otherwise stop you from woodworking -- no question about that. I think we should consider too, though, that there is the art of living making the unmade into the made that has hidden benefits we might not always recognise. And I mean by hand as a usual course in making. I recall one time needing some coving for a piece I was making and needed to conclude for a birthday gift. In the machine shop, I rigged up the tablesaw with a diagonal fence to run my board against. By raising the blade incrementally, the cove came to be in about fifteen minutes. Once roughed out it needed scraping with a round scraper followed by sanding. When it was shaped and ready for mitring and then fitting, I realised how skilless the whole thing was. An hour later I felt robbed. Up until that hour, the whole piece had been so thoroughly satisfying to make by hand that I actually didn't really want the work to stop. But I hasten to say here that I never saw it as many people do when they say, "Well, I did cheat a bit for this or that!" when they used some power equipment to cut something like a dovetail. It wasn't me cheating by using a piece of power equipment. I did cheat though. I cheated myself of the satisfaction I now get all the time, every day in the making of things handmade. Do I cheat by using the bandsaw to rip big cuts? Not a bit of it. Would I cheat if I had weak parts to my body through a disease or an injury? No, no, no!

So just when do we cheat? I am not sure that most woodworkers do. If I were a woodworker and I chose to do most of the work with a machine, many jigs and so-called power tools, there is nothing 'cheaty' about it. If someone ordered a project and said they wanted only handwork and no machines to be used and I did it all or even mostly by machine, I, me, personally, would be cheating them. It is not so easy to define handmade in our day and age as most machine work is for some very strange and mysterious reason referred to as handmade. But if wood is planed and trued by machines like planers, thicknessers and then sanding thicknessers too, and then the remaining work of joinery, fitting, shaping and so on is hand cut and done with hand tools, then I believe it to be hand made even though some machines were used for dimensioning. Somehow, for me, it's when the hand tools and the hands, the manipulation of the tools as in hand tools and not machines, have the final say, that makes the difference. For myself, I understand how captivating machines can be, especially if you never mastered hand tools. Most hand tool operations can be adapted to machine processing. I once devised a method for routing out bowls to wooden spoons that could be completed identically in every spoon a thousand times in as many minutes. At $18 a pop that would have been good production along with high profitability. After the first few, I ditched two days of development to set up the work and went back to hand-cutting them with a gouge. Why? They were not handmade anymore. I allowed a brief skirmish with an invasion of an enemy to my wellbeing. Going back to sanity, I ended up where I could comfortably carve a bowl of the spoon in about five minutes, depending on the wood. Cherry, maple -- easy!

It's less about cheating others and more about cheating yourself. In business, with competitors, you may have no choice. In high-demand, highly competitive countries and cultures, where life can often indeed be cheapened so, as they are often based solely on economy and commerce, marketing and the industrializing of life, family, education and on into medical care and so on, the choice is mainly taken away from you. This survival of the business-fittest has little to do with holism for individuals to stand alone as individuals fully relating to the greater whole and good of society around them. Competitor supremacy is becoming more the ambition and goal even though it tends to cheapen life alongside its product. As an example, what happened to the Industrial Revolution? It just kept growing and ultimately was exported to the four corners of the world to create a better, more affluent society. From car manufacturing to bikes and bandsaws all made now in Taiwan and then chips (not fish and . . .) in Asia creating what? More good old competition. What value human life, really?

Comments ()