Why?

The result of me showing the difference between a newly arrived gents saw and then one touched up with a half stroke from a fine saw file to each gullet met mostly with wonder and hope from 98% of those following to learn and better understand. Then there's a cluster of bitter retorts and mocking from those, well, in the so-called professional realms be they carpenters or engineers. Thankfully, their influence is small if existent at all. Their negative comments usuallyshow that they missed the whole point. As an example, one engineer focussed on the fact that I returned the saw file for a second pass and should have lifted it off the metal because keeping it engaged damages the file. Whereas this is true, and generally it something I never do, in the case in question I was using an ultra-fine saw file in ultrta-fine saw teeth. To disengage from the gullet meant it would be most unlikely that I would reengage the same gullet for the second pass and would thus make unequal gullets to the teeth. The engineer discounted the lightening of the reverse stroke in readiness for engagement. The saw file would not be damaged in any way.

Now, these are men who at one time would have quite simply stopped work, pulled out a Stubbs or Nicholson saw file and sharpened up the teeth. Unfortunately, for the last maybe 70 years or so, such men seem mostly to no longer exist. Indeed, they no longer even own sharpenable saws but have bought into the and indeed recommend the throwaway consumerist versions: they would rather buy plaso-handled hardpoints in packs of five or even a dozen than take literally a five-minute break with a saw file to quickly restore the saw teeth to new perfection. Now please, please do not tell me that they can't afford the time to do that because time is money and so on. Most of the working men I see and know and have worked alongside often take time out for a ten-minute chin-wag. And hear this, if you hand sharpen a saw you can still carry on a conversation or plan your next move no problem. Here is another: this commenter said he had, "been a professional carpenter for 60 years and never attempted to sharpen a saw because it had to be done by a professional technician." That would likely make him roughly the same age as me and saw sharpening was indeed one of the first sharpening tasks I learned from George. And what about this bit too: "Saw sharpening should only be carried out by a trained specialist otherwise you will only ruin a saw." This is the kind of thing that once undermined those who wanted to learn and master and do things for themselves. I have a couple of friends, software engineers, who attended different courses over a number of years and made beautiful hand planes with dovetailes steel soles and Norris style adjustment for depth of cut and lateral adjustment. It wasn't that they wanted specialist planes so much as the challenge of making them and to own the knowledge and skills needed to make them. Watching a man build his 4,000 square foot log cabin from the ground up in the middle of nowhere in Texas when he was "just a welder" working for Union Carbide, Houston all his life was another classic when all of the carpenters building a house a couple of miles away were waiting for the cabin to fall down. Three decades later it's still standing and though he is gone his kids and grandkids are still weekenders there and loving it.

In the same way, some men will say of a good woodworker, "And she's just a girl!", so too some will say, "And she's just a software engineer." or, "And he's just an accountant." Just as woodworking is non-gender specific, it's also available for anyone who wants to take the time to learn it.

So, thank goodness for us amateur woodworkers and whatever else we are. Like me, everyone has a lot to offer the craft and we have replaced most of the so-called professionals to carry the craft forward. Thank goodness some of us want a handsaw or a tenon saw we can own for a hundred years simply by learning to sharpen and set them. Thank goodness I can now safely say that the craft and art of saw sharpening, a cultural craft 300 hundred years old to date, is now safe and sound in the hands of those who will take the baton from me and pass it on for generations of amateur woodworkers yet to come and worldwide. This is a true success for the work we at Rokesmith do. It may only be a tiny percentage, but it is a cog in self-sufficient and sustainable and responsible crafting. Reversing the trend of buying disposable pull-stroke saws and western hardpoint push-stroke saws is as yet incomplete. Still, thankfully we can take dominion where we can and the more opposition I get from professionals in every sphere the more I can measure the success of the work we do.

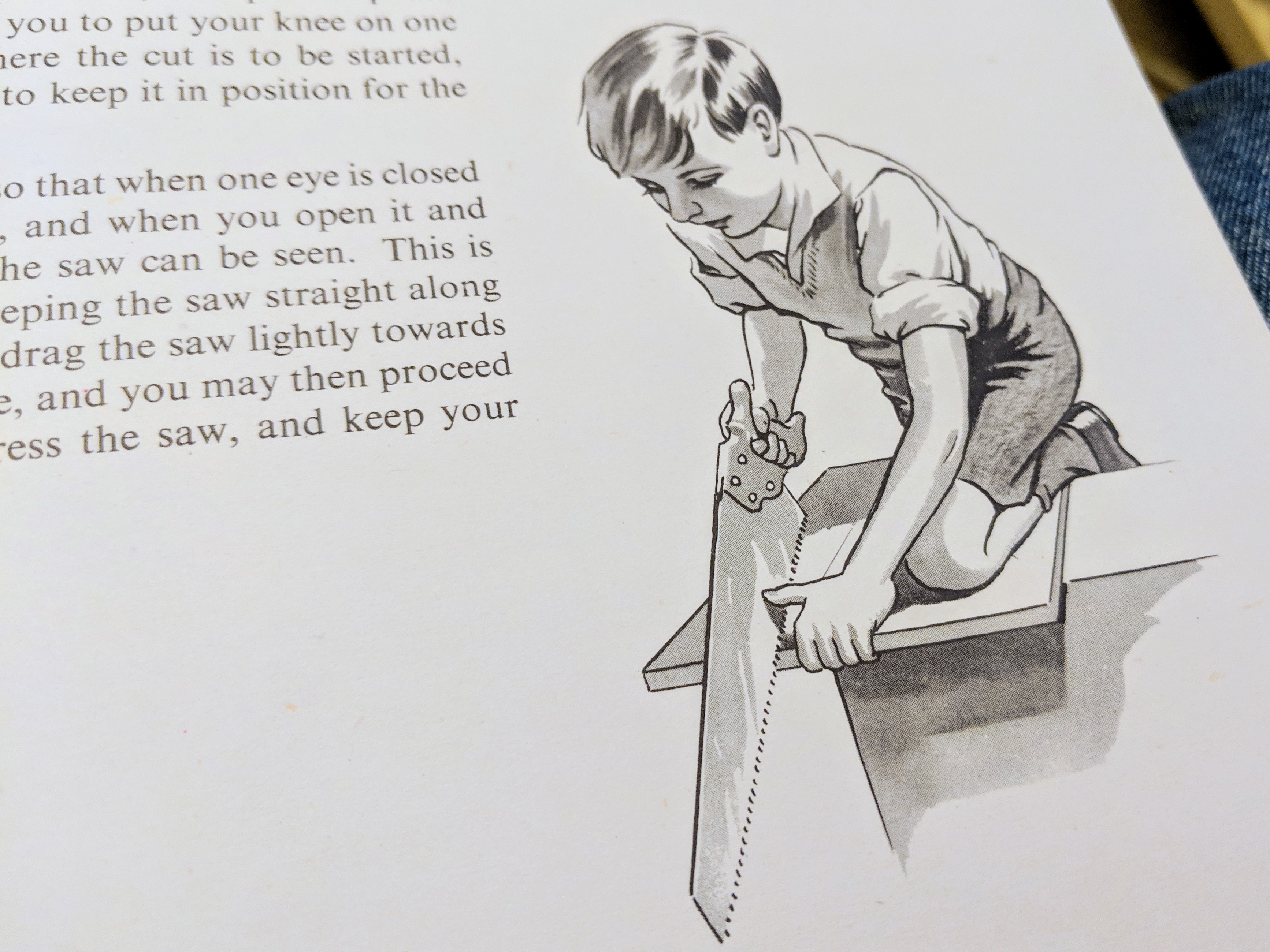

It goes without saying, there is a large percentage in the carpenter's fraternity who don't diss the work we do and both learn from our efforts and contribute to it. Hopefully, we can keep on encouraging people to gain mastery. First efforts are the first steps. Rhythms of working, measured strokes, pressures of even measure, things like this, take time to establish, but fear should always be questioned and then challenged and the best way to challenge fear is to simply do what is needed.

Comments ()