It Only takes Two Sticks . . .

. . . to start a fire

A single log rarely burns when started alone without the input of something else to cause the burn. Most fires end when one log burns through too early if two logs are used: the second log relies on the outgassing from its partnered log that's caused through expansion and contraction, heat and so on. One or both puff and blow and by this they ignite one another reciprocally until both crumple into ashes. Of course, the more logs you have in the fire the more the fire gives a steady burn. The burn rate is controlled by the damper which controls the intake of air to the flames. I'm watching my stove and as I watch it burn this particular morning it's still dark outside and a class will start in roughly two hours' time. The blue norther blew in overnight and caught me off guard as I rose from my warm bed and to catch the chill in the air. I quickly lit the ready-laid house stove before I made my coffee and left for the shop. The temperature dropped from 80º Fahrenheit (27 celsius) to on or just below freezing. It's mid-January in Texas. The cardinals are bopping above a field filled with a wave of American robins swooping and swirling waist-high on the top pastureland and we have all the colours of the rainbow in the painted buntings, American goldfinch and many others skirting and scouring along the edge of the woodland for food.

I'd left the wood burner in overnight with a large, dry juniper nestled in the evening coals and the damper closed down. I needed to get the heat up for fifteen students who were used to centrally heated homes, warm cars and trucks and city offices. There were plenty of dry logs loaded and stowed on the front porch and I passed them through the windows to place by the fire. The cold would be in throughout the day.

All the benches and tools were ready for the beginner's class and so too the first exercise wood for the housing dado. My feelings were a mixture of excitement and apprehension. Things can always go wrong with a class. A vise freezes for no apparent reason, wood splits when it shouldn't and then there is a slip with a chisel into a finger where the owner is on blood-thinner medication and it won't stop dripping everywhere. But this morning I feel more confident than in my earlier classes when everything seemed to be more of an experiment. I love the sense of anticipation that many more than just one or two are going to be completely mesmerised by the whole immersive experience. For most, it will be the very first time they've handled a truly sharp chisel or plane. For some, it will be the first time they ever picked up any woodworking hand tool at all.

As I feel after the impact that this class will hopefully have on everyone before they arrive, I bathe in a new kind of stillness I haven't experienced before. It's quite visceral in my surroundings, right there between each of the benches, a type of warmth permeating the semi-silence. As the wood pops and crackles inside the thick steel of the stove barrel, I find a settledness in knowing this journey is only just the beginning of something bigger than me. I doubt that anyone could foresee that hand tool woodworking was very much a dying art form. Certainly, I never saw that I would be doing this recovery work for three decades. Who would have thought that I would be beginning a true hand tool woodworking school and one of the rarest types in the USA? Back then there was only a handful of schools available. Little did I know it, but within a year that school would become year-round and full-time. Students would fill every vacant space as soon as they were offered and be making everything from turned bowls to guitars and rocking chairs to tool chests. I was on the verge of writing all my own woodworking curriculum because what I wanted to say didn't yet exist. I began to write articles and how-to books, design courses and ultimately train many a thousand student woodworkers face to face from throughout the USA and around the world.

The redwood cedar-cladded workshop nestled neatly amidst the Ashe Junipers as though it had been there forever yet the building was less than five years old. Eighty feet long and forty-feet wide with a high vaulted roofline eighteen feet to the glass-windowed cupola created a truly pleasant place to work in the fall, winter and springtime. From here I designed and made different pieces of my furniture on the days when classes weren't on. In the beginning, I held classes only on Saturdays. As the classes became better known I increased to Fridays and then Thursdays. It took a little more than a year to go full time and the other makers that once occupied the benches set up home workshops to work from and I pretty well stopped making to sell as my primary income.

The first student rattles the brass doorknob, swings inside with a flourish and a broad smile. "Hi Paul!" she says, with a Canadian accent. "Is this where we are supposed to be?" She strains under the weight of her backpack and a bag that looks full of heavy tools. 'This is it, Yes!' and she drops everything by the stove to get warm.

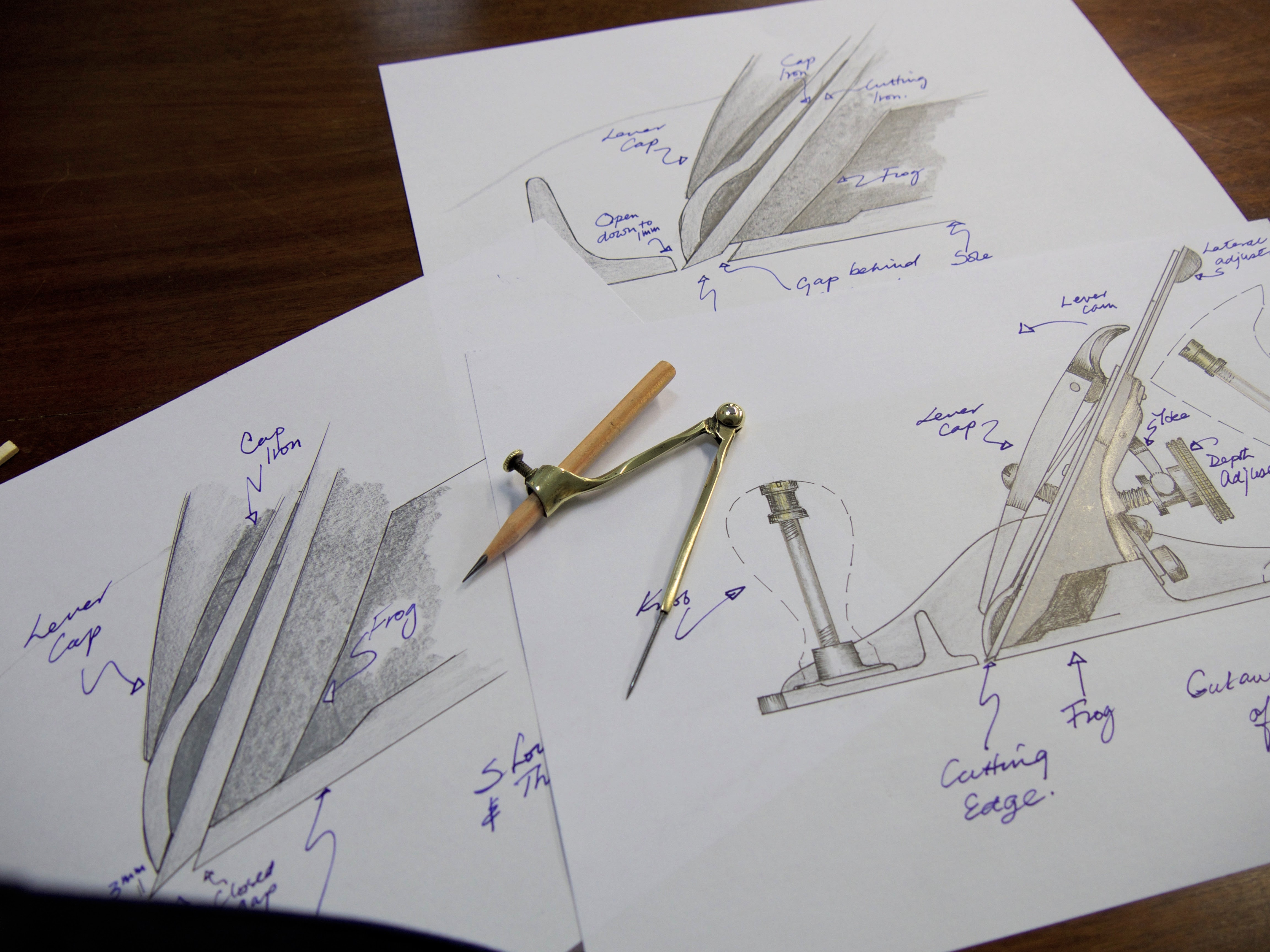

One by one and in pairs a dozen others gathered around the stove with hot coffees and smiles. Soon they drift between the benches, pick a slot by a vise and flip some of the tools to look at the cutting edges or the names on them. Some go for spots nearer to the fire and others look up for the best light. As it was in the beginning and is still now, there are no premium tools per se but tools well proven to be remarkable at what they were designed to do. Jane, the first student, wants to be nearest to the teacher so she sidled up to the bench next to mine before everyone else arrived in the shop. Her excitement is contagious and she serves to make everyone feel at home and settled straight off. When she laid out her tools she was the loyal Canadian: everything she had was Lee Valley Veritas. Watching her up the low-angle jack, I wasn't sure how she was going to use it with wrists that rocked and swayed from side to side just lifting it. In the classes, we couldn't really accommodate students bringing in their tools to use. For various reasons we changed the policy because with the best will in the world, student tools might not be equal to the task and we didn't have time to start tweaking planes and chisels to get them to work well throughout the class.

Dead on nine, I called everyone around my bench saying, "Can I have you around my bench please?" Most classes and sessions started that way.

It's hard to describe an atmosphere that defies words. Does the word even exist when a man or a woman who worked as a producing artisan most of their lives stops the conveyor belt others are on just long enough for them to hop off and start a new journey? I'm asking myself this because my work seems so different to every other entity I have seen since those first days of classes. I mean I'm pre-social media at this point and even pre-internet for me. At this point in 1995, I have never used a computer, digital cameras have yet to arrive and when they did a 1-GB memory card cost me $1,200, today we get 128-GB SD for £15.

Introductions broke the ice as did telling the others what your hopes and aspirations in coming were. I had the then vice president of Intel there. A NASA scientist spread his tools on the bench and then another who worked for federal government was looking for a way out to retire to. It was a mixture of professionals, dentists and engineers mostly. Within 30 minutes the atmosphere completely changed and it seemed like we had all been friends for years.

As I sharpened a set of four chisels in a few short minutes, a minute or so apiece, and explained what was needed to get them surgically sharp, the lights were popping into electric smiles. The first hour of every class I taught was intended to deindustrialise the whole process of woodworking and especially sharpening; just to simplify each of their futures. What I once took for granted through accumulated knowledge over decades, I parcelled up into bite-sized chunks. For them, it was something they saw as nearer to miraculous. Saws and sawing was handled in front of one another at my bench. Through this I was best able to critique their techniques and explain the flawed thinking most of them had. When they used the saws the saws snagged and grabbed. When I used the same saw the saw sliced through the wood smoothly and dead to the line perfectly. Within an hour they too had a control they'd only dreamed of owning and thought belonged to others and not them. We were just minutes from them making their first woodworking joints.

These early days of teaching, of opening my shop up to others, undergirded the whole of what we do today in conserving the art of hand tool woodworking. What undergirded that and still does today is my daily life as a maker designer and not a YouTuber or blogger. There is no image of being something but the doing of doing something as a lifestyle. I think back with very fond memories of people and conversations, of the assembling of men and women around the bench, the woodstove and the picnic-0table conversations at lunchtime and break.

So here we are, many logs in a fire and all seem to be burning brightly around the globe. Some still get in touch with me even from pre-1995 when my more official work took hold. Every so often one of the children I taught in evening classes from before 1995 will send a message thanking me for the evening classes when we got together in a dozen or more every night with different age groups for local families. Teaching from this long-term background equipped me to become the teacher with a difference. What a life!

Comments ()