Dos and Dont's II

Woven throughout woodworking there are the rights and wrongs to the way we work wood that defy being written down and yet the information would be very helpful. Read any book on woodworking and no one wrote about the direction of the grain when cutting dovetails. It's a foregone conclusion that they go at the end of the sticks of wood and not sideways on. Outside of woodworking realms, to non-woodworkers, sideways on dovetails would be admired as exemplary of good craftsmanship. Without good guidance as to the whys and wherefores, we can all be ignorant.

There is a very brief but informative video clip on my FB here, (under two minutes) to show a specific reason why we generally orient our dovetails according to the intrinsic strengths of the wood used. Inevitably, 98% of all of the different woods are able to be split along their length. Whereas some are prone to splitting along or with the grain, others I have encountered have interlocking grains that defy splitting altogether. I am convinced that these woods could be dovetailed any which way you want to dovetail no problem. That being so, would that still make it a wrong way to dovetail? Would you fail the exam or contest or competition because of tradition? I once used a 5-ton log splitter to split an unknown tree limb and stem and never split a single piece of it. Its resilience caused the hydraulics to burst their seals and cost me the repair on top of the wasted hire charges.

Because of the growth direction of the tree, the grain in the wood we get is generally unidirectional along the main stem until the branches splay and spread to become the leaf-bearing canopy. The commercially harvested and processed wood sold to us comes from the stem only and not usually the branches. This results in straight-grained wood with greater strength and resistance to pressure in one direction over the other. Wood only splits along or with the grain and not across it; that's unless subjected to some very extreme force which is usually breakage rather than splitting. When we cut the tree stem into boards and beams the wood has greater resistance to bending and cracking along its length. In continuous grain, the wood retains this property, but when we cut across the grain as in the short cuts for the splays of the dovetails or in between the pins, the resistance to pressure and the risk of splitting is radically reduced and so an unwritten law exists to those of us who accept and work within the natural limitations and properties of our materials. It does not mean we cannot experiment, try something different, just that we should be prepared to change direction in view of our findings.

In my view, it is a good measure of an artisan's character when he or she gives consideration of the wood and tools they use. It's no longer that they have been told to do this or that but that they have internalised care as being intrinsic to craft and intrinsic to the person they are. If someone tells you never to cut a dovetail this way or that way, to sharpen a saw this way or that, or use this plane for long grain and a bevel-up plane for end grain, you can accept what they say, but doing as I did, gives clearer understanding and thereby acceptance in your findings.

Experimentation is pivotal to knowledge but the knowledge should become yours to own. In other words, experiment all you want, but be prepared to change your mind and your opinion on things. The only reason I generally do not favour bevel-up planes over bevel-down versions like the Stanley and Record bench plane versions is that there is only minimal advantage and only in some possible cases. My experience with bevel-up planes is that they generally work well across or at a tangent to the grain -- on end grain and mitres, such like that. Experience tells me that the bevel-up plane is more than likely to tear the grain quite deeply, fifty times more likely than a bevel-down version. Inevitably, owners of the bevel-up planes are highly defensive and will contact me to tell me I should use this or that plane iron or that bed angle. The truth is though, in the moment, as you plane that surface on that very unique section of wood, before you know it to strategies as advised, it's too late. The damage is ALWAYS already done and when you cannot predict it ahead of time. The damage is done BEFORE any remedial action can be taken, usually irreparably at that.

When something is revealed to you in the outcome of your trial and error, your experiment and whatever, you suddenly own it; as experiential knowledge, it becomes yours for life and you can then rely on it. It is always good to recognise the limitations of all we call work and to then acknowledge those limitations by working within those limits. Knots in many species result either in weakness or strength. When a man I worked with in my apprentice years sought out the knottiest piece of cherry from which to make his mallet head it needed but few words for me to understand his reasoning. Some knots work and some don't. In his case, it was the interlocking grain surrounding the knot and extending well into the adjacent wood that he sought. Cherry on its own is not the best wood for a mallet because of its lack of density and its lack of resistance to splitting as well as density. The wood surrounding knots is almost always denser and indeed omnidirectional too. He was prepared to work through the omnidirectional grain when chopping out the mortise to receive the handle. Wood that many might reject can be a good source for a mallet head. Look at turning wood for sale. This wood would one time have been binned but when woodturning came into hobby realms such wood became sought-after "character wood" for bowls and vases. Look for even density though. If there is a central hard spot it needs to be surrounded by support wood. Just an added point: some woods fracture internally under malleting blows and some woods consolidate. My cedar elm mallet from a Texas tree is hard and dense and evenly so throughout. It's the perfect mallet wood but not at all readily available. Using it through two decades plus five years it has become denser. Bois d'arc has given me a couple of mallets of even density weight and hardness too. Mesquite is twice as hard as oak but not a particularly good choice for a mallet as the grain collapses. In this case, I would look for something with dense, interlocking grain and within the branch range of the stem where the grain becomes denser during growth.

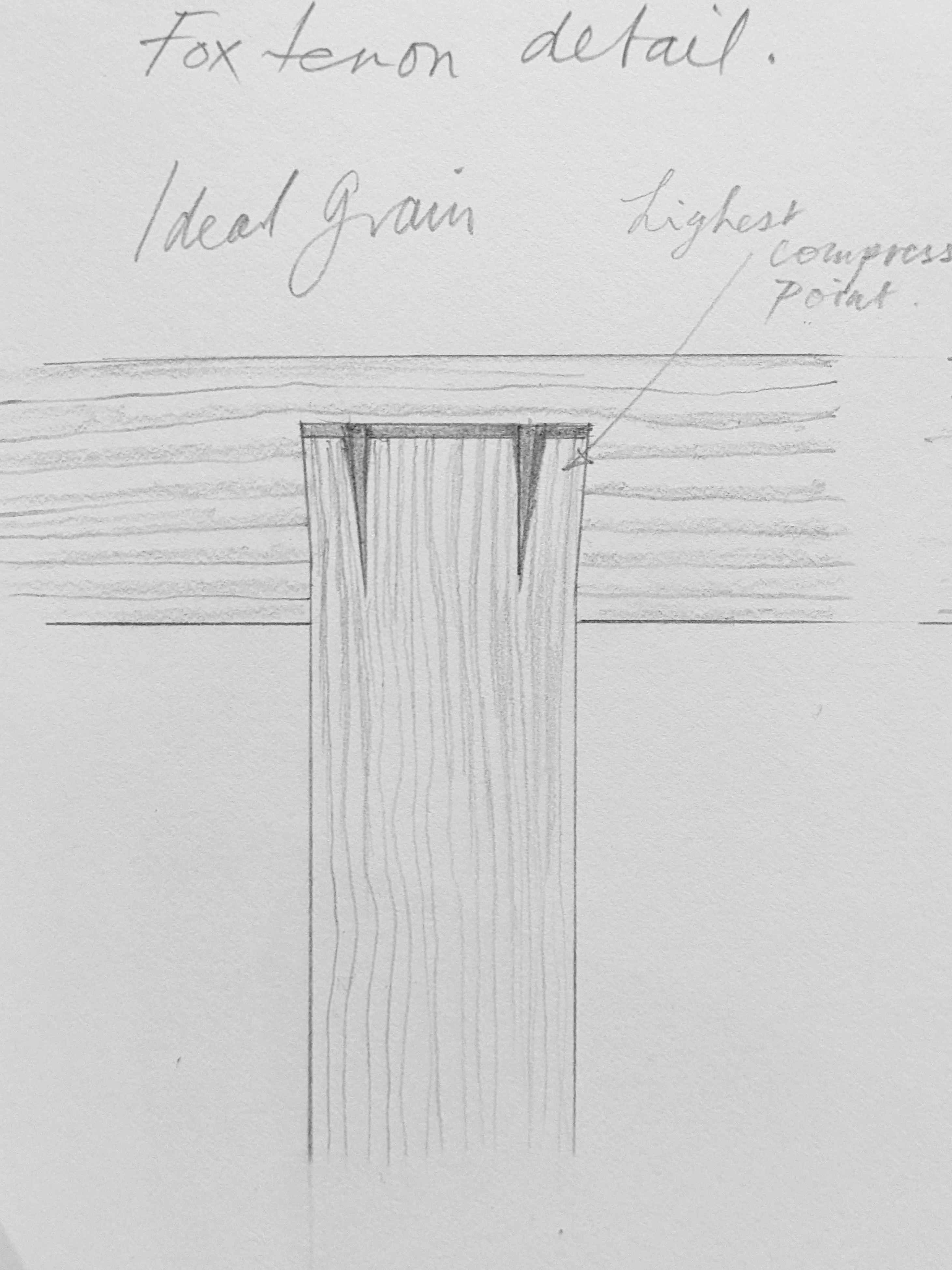

In crunching the alternative dovetailed examples, thinking about how it felt at the time, in the minute, I did feel a wall of resistance, a reluctance within me that I had to push through knowing that I had created something well intending to destroy it. I found, of course, that it went against the grain in that I am always making for longevity and permanence and never so short a life to intentionally destroy something I had just made. I have only done this handful of times in my 57 years of woodworking. The last time was with the fox-wedged mortise and tenon, you might recall, where after it was done I cut through the whole to see the effect of the spread within the mortise. The fox-wedge is not a common joint but an extremely useful one with specific applications. It at first seems destructive and time-wasting, but the visual impact is far more informative and long-lasting than an explanation alone and so that compensated to make the effort well worthwhile.

Destructive though it seemed, the examples show how we as crafting artisans must consider the grain and work within the limits of its natural, organic structure. To do this we must understand more about grain and what it is. before we become makers we see and understand wood without depth, as a surface, little more than a photograph. Once we get inside the wood, experiment with ideas, split it, saw it, bend it, work it with our tools, flex it in our hands and fingers, we start to gain some deeper insights and gain understanding of its substance, but we must see it as ever-deepening. We have not yet arrived but we are on our way, for even then we can only say we understand wood and grain by degrees. We better understand the characteristic of different wood types in the working of them over a period of time. Even people such as myself, lifelong woodworkers, only really know the woods at a very limited level. Take one species alone, Redwood pine, for instance, a wood I have worked with almost daily over almost six decades: each time I work it I learn something new from a pocket of resin sealed for decades and then seeping as though just woken from sleep, the undulation of a grain part that diverts from the common path of all the other growth rings, as though something impacted the tree 50 years ago, or a hundred. I see something different and consider myself choosing a different approach because of what I see.

I have read information by authors known as experts, professors and such, I mean. I recently read a book by such a person explaining many things trees and wood. All quite interesting stuff, facts about ancient trees, forests past and present, how life is recorded in the growth of tree fibre, things that we might know but from a different perspective. At the conclusion of the book, it was evident that this particular author had not worked with wood as a woodworker even at the most minimal level. She had analysed data, processed information and presented it as an academic work. It was as if the work was presented as a deeply informative work when there seemed to be a heart missing from the whole. Primarily it was informative, a little dry but packed with what I might call relational knowledge rather than experiential knowledge. It made me wonder if she had taken a year or two out, removed her academic hat and made some pieces as everyone here does whether the book would have taken on a completely different dynamic without losing any of its present content. I believe this is what Bruce Hoadley did with his book Understanding Wood. From beginning to end his book is imaginative and totally readable. By relational knowledge, I mean accumulating academic evidence by way of reasoning, categorisation, planning, quantification and academic language. Supposedly, relational knowledge represents the core of higher cognition. I question this as being presented as fact in many cases. A calculation formula on a page representing moisture content alongside a pair of scales registering weight at the bench carries the same meaning but not really. Experiential knowledge is knowledge gained through the more sensory experience of handling our material rather than merely observing. Seeing even the most minute detail on a screen is still filtered to our mind's eye through if you will a veil. These two ways of knowing are indeed radically different and give different experiences. On the one hand, my splitting the wood in my vise gives me a multidimensional understanding and of course, reasoning through the experience. The wood popping, the use of tension resulting then in the release of smells and sound, vibrations sensed, visual ability to focus and change focus from one part to another all broaden my understanding second by second as each pin or dovetail pops and fractures and splits off. Though I did my best to produce a video, it is still not the same as creating the alternative dovetails and then turning the vise jaw to apply pressure to breaking point to the whole.

My conclusion is that everything is necessary but mostly for different reasons and for we who work wood things are very different. Some people measure the density of wood in the lab with lab coats on and using more sophisticated measuring equipment, whereas others by the sensed pressure through a plane planing, a mallet blow on a chisel or saw cutting into the wood stroke on stroke, blow on blow and swipe on swipe. In my world, I know that the density, strength and resilience of wood is not singularly measured but one with shifts and changes throughout a single board. I am often amused when I read lists of wood densities because my experience tells me differently. I do understand that these are two very different ways of knowing with one result digitally tapped in as computer data, the other recorded in the mind and body.

Comments ()