A Legacy For Life Lived

I don't think that we should ever lose sight of some basic but very interesting realities with regard to the craft of hand-making furniture and other woodwork. How often do we fail to understand that the joints we use today have been with us for centuries and that despite interesting developments in technologies no new joint exists that didn't exist in one version or another 200-300 years ago? Dowels, biscuits and dominoes, of course, are not technically joints in the same way fastenings like inserts, fixing plates and screws in sloped holes don't qualify as joints and joinery either. Generally, these third- party components are simply developments designed for speed and to replace both joinery and the skilled craftsmanship of old, not actually join it, if you will. Here's another interesting truth too. No new hand tool exists that didn't exist in one form or another 300 years ago. By that, I mean that whatever we have now we had in some different form in the past. I think a good example of what I'm suggesting could be the Shinto saw rasp. Is this tool with its saw teeth the same as a rasp or file or is it a completely new tool? Can the way it is made and the outcome in its finished form determine it to be a completely new tool? Is it the action of use that determines its name? Who knows? Try googling the name Shinto to find the maker's site and you will end up studying a Japanese religion or on a hundred seller's sites selling it under the title 'Shinto Saw Rasp'. Shinto separates the Maker's name and hybridizes saw and rasp into one name sawrasp. Of course, no one should be deceived by the title. It does not saw wood as such but it does capitalise on both the use of teeth as cutting edges and rasp as in a barbed plane.

The manufacturing procedure created a method of making something to work with that actually gave us a good alternative tool that worked well at a fraction of the cost of a hand-stitched rasp. We then gained from a mass-made tool that could be made and boxed up in a matter of seconds with no human hand touching anything more than a machine's start and stop button. The work needs no more input then than a man or a woman watching a quite skilless process that parallels most saw-making with stamped-out teeth, machine-filed cutting edges all as tap together parts with a couple of screw bolts or rivets to hold things in place. A Shinto is a pressed-out framework of saw teeth in a length of steel banding crimped into a diamond pattern with rivets holding the whole in place and requiring no skilled metalworking. It's two-sided, fine and coarse teeth, giving us two rasps in one, making it a great strategy for fast stock removal followed by fine refinement in a single tool simply by flipping the rasp over. It was indeed a truly ingenious and brilliant idea that created a rasp-type tool that worked as a tool almost equally to a bona fide hand-stitched cabinet rasp at a tenth of the cost (shop around I have found £28 ones for as little as £13 without eBay or Amazon intervention).

What Shinto has is something every toolmaking company dreams of designing and engineering. If they could come up with one that had a round face too they would be on another winner and though no one is doing it it is not at all complicated to do. I have already worked out what that would take and how that could be done. A hand-stitched rasp on the other hand produces the same or better work but takes many years to master the skills of making such a tool. A hand-stitched rasp gives its user a level of quality, control and accuracy no other hand tool can match and does so with a consistency that is repeatable in every version made. The man stands or sits and stitches the steel for half an hour or more per tool depending on the number of stitches per square centimetre, decides on the pattern and the number of stitches per distance travelled and records the 'fingerprint' of his making such a tool in the outcome of his work. This truly sets him apart in the art of tool-making simply because his hands, mind and body deliver all the energy and direction and no machine can replace these skills with the same qualities he/she perfects. Such skilled making defies engineering, in the same way, blacksmithing a blade from hammered steel does. There is no dialling in synchrony as with machining planes or the chisels of a mass maker and no rotary cut governed by CNC seems able to quite approach the skills of a hand maker who master the art of hand making. Pure skill is earned and worked for by patient makers in the making.

I wanted to spend a little time on that just to show we have a low invention rate in hand tools in three centuries and I rack my brain to think through to find something new in hand tools. In the past, we had wooden tools that worked as well, and much better than most of the all-metal versions. None of them were rejected because they didn't work and work extremely well, it was the introduction of mass-made cast metal versions that changed the game. Cheap methods of making the main body displaced the skilled makers cutting in the throats, squaring up the soles and sides with hand planes and much more. Waiting four years and up to a decade for wood to fully season before production could begin was suddenly eliminated. Even so, it took almost a half-century to transition from the realms of skilled planemaking to the bolt-on assembly of soulless parts in the planes we know today. Why? Because no matter what you think, compared to a wooden sole, all metal planes stick to the wood unless you lubricate or wax them from time to time as you work a surface I cannot think of a wooden hand tool that was replaced because the metal versions did better except possibly the shoulder plane as more a luxury item rather than an essential one for most woodworkers--perhaps a plane or two like side rebate planes possibly.

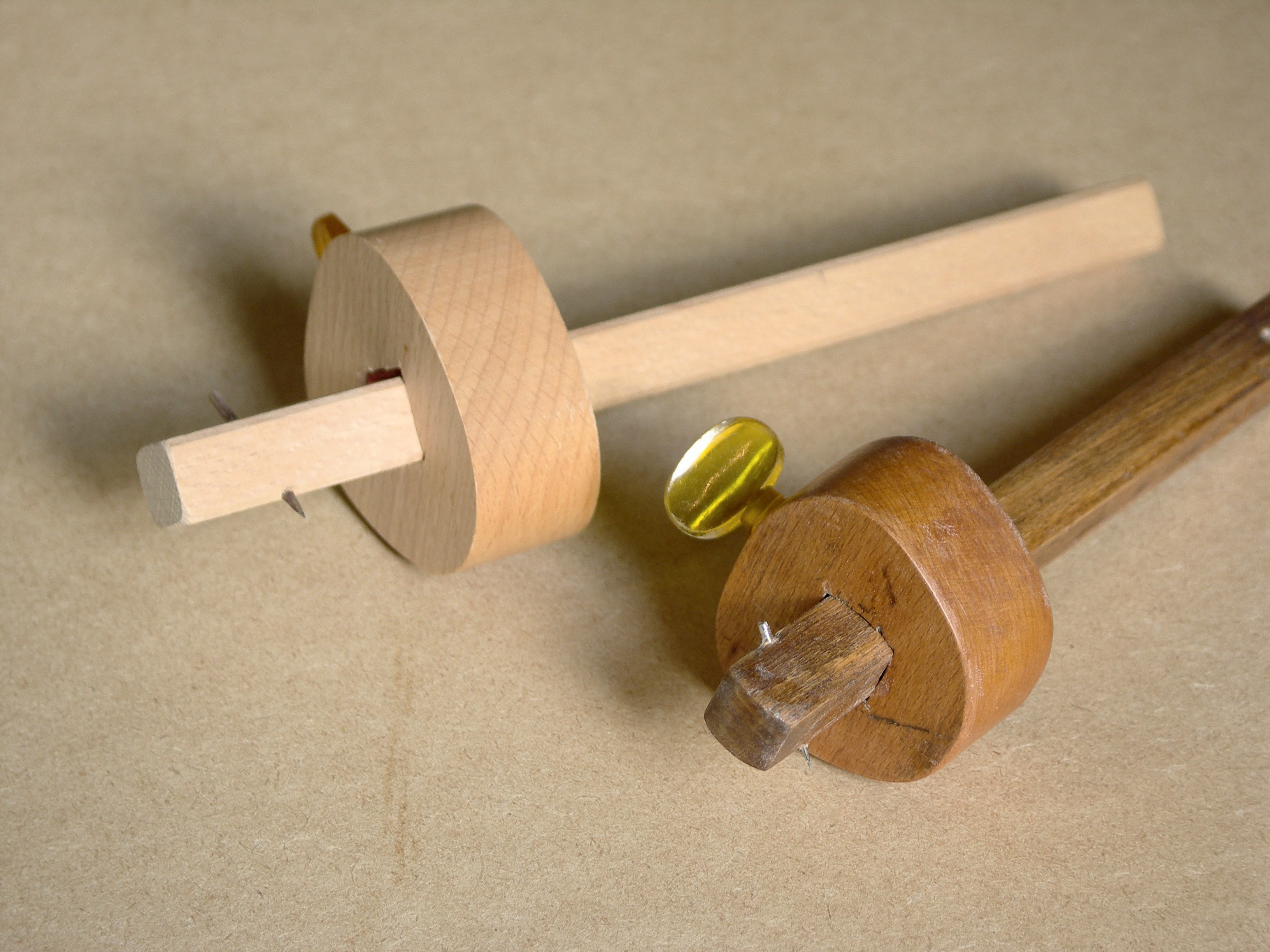

Above is another example: why have we tolerated angular marking gauges that are awkward and really quite uncomfortable? Then too, why did Stanley think that they could fob us off with their plastic versions? It's because they can get away with it when there is no competition there is no change.

But mostly I am talking about wooden-bodied bench planes and spokeshaves and planes like tonguing planes, compass planes, curved-both-ways planes. Of course, no metal plane could or did ever successfully replace a vast range of rebate and moulding planes, over 300 of them. It was the power router that ousted the moulding plane range in the same way machines displaced most hand tools altogether. I do not believe that hand toolists like myself refuse machines and machining because they live as so-called Luddites. This is a mere insult and nothing less. We do what we do for a wide range of really exceptional reasons not the least of which is we reserve our right to literacy in skilled working and making; we love the concept of becoming and being fluent in the language of handcraft and enjoy the high-demand handtool woodworking requires of us. It's dead simple really. Hundreds of thousands of woodworkers including myself choose to now enjoy a different way of life that gave us access to a health-and-wellbeing lifestyle we could gain in no other way. If the handwork, the methods and techniques that work so very effectively, make me a Luddite and give me such good physical and mental health along with peace of mind and contentment then bring it on all the more, I will take the name willingly.

Thousands of woodworking joints have been devised and developed by inventive joiners through the centuries. The majority of these joints will continue to go unused and we furniture makers rely on surprisingly few, a handful really. Why? Well, many of them are quite specialist and now obsolete through other developments in metal and plastic, but mostly they are relatively impractical for furniture making. Outside of the specialist realms, most of them are unnecessary, time-consuming to make and often cannot be applied to the work we are engaged in. Even tradition can become whimsical in the presence of a changing culture. That said, making a complex and obsolete joint might present intellectual and physical challenges and also have a therapeutical value and thereby find its place in an individual's life.

The basic ingredient for my teaching woodworking has always been to keep simple what is always simple. I began almost three decades ago with this undergirding. Before that, when I started to take on apprentices one or two at a time for a focused year or two, it always seemed complicated because most people factored the essentials as including machines. The course for every new starter was the same and remains so. I also taught a couple of dozen local children in the evenings from 7-9 pm three or four evenings a week from February through November.

Three joints with two or three variations give us the lifetime joints we return to every day through life as a maker. Does this not strike you as an amazing simplicity without any hint of being simplistic? Adding machines takes a huge investment and a prohibitively massive footprint in our precious garage, shed, loft or cellar space. The answer to real woodworking suddenly becomes so clear and straightforward when you see it for what it really is. This is the legacy left to us. Now think the more of this if you will. Every exercise move you might make in a gym, every weight lifted, step taken, muscle moved, stretched and strained in positivity will take place hour on hour in the workshop of your garage woodworking. The reality is you may never need to use a gym again except for your preferential training, sport or whatever.

Additionally, and more importantly in my view, you will have the fruit of your labours in the same exercise plus what you make to take indoors or give to friends or, dare I mention it, actually sell things you make for modest additional income? In preparing 20-30 boards for two new cabinets I was reasonably breathless every hour after an hour or so of hand planing and sawing. Edge-jointing the meeting edges caused me to strain muscles in the flexing of the plane to meet and make 90º edges. The demand encompassed the whole of my upper body, my core muscles and then too my legs. This plexus of every sinew and synapse causes us to thrive in the zone minute by minute and the result is smoothed and sized wood. The effects are almost magical and no less than running a marathon in good time or rolling the surf inside the tunnel, hanging off the rock face a hundred feet above the ground in our youth. Mostly it is about conquering, tackling our fears and doubts. Overcoming wondering if we can by seeing we did!

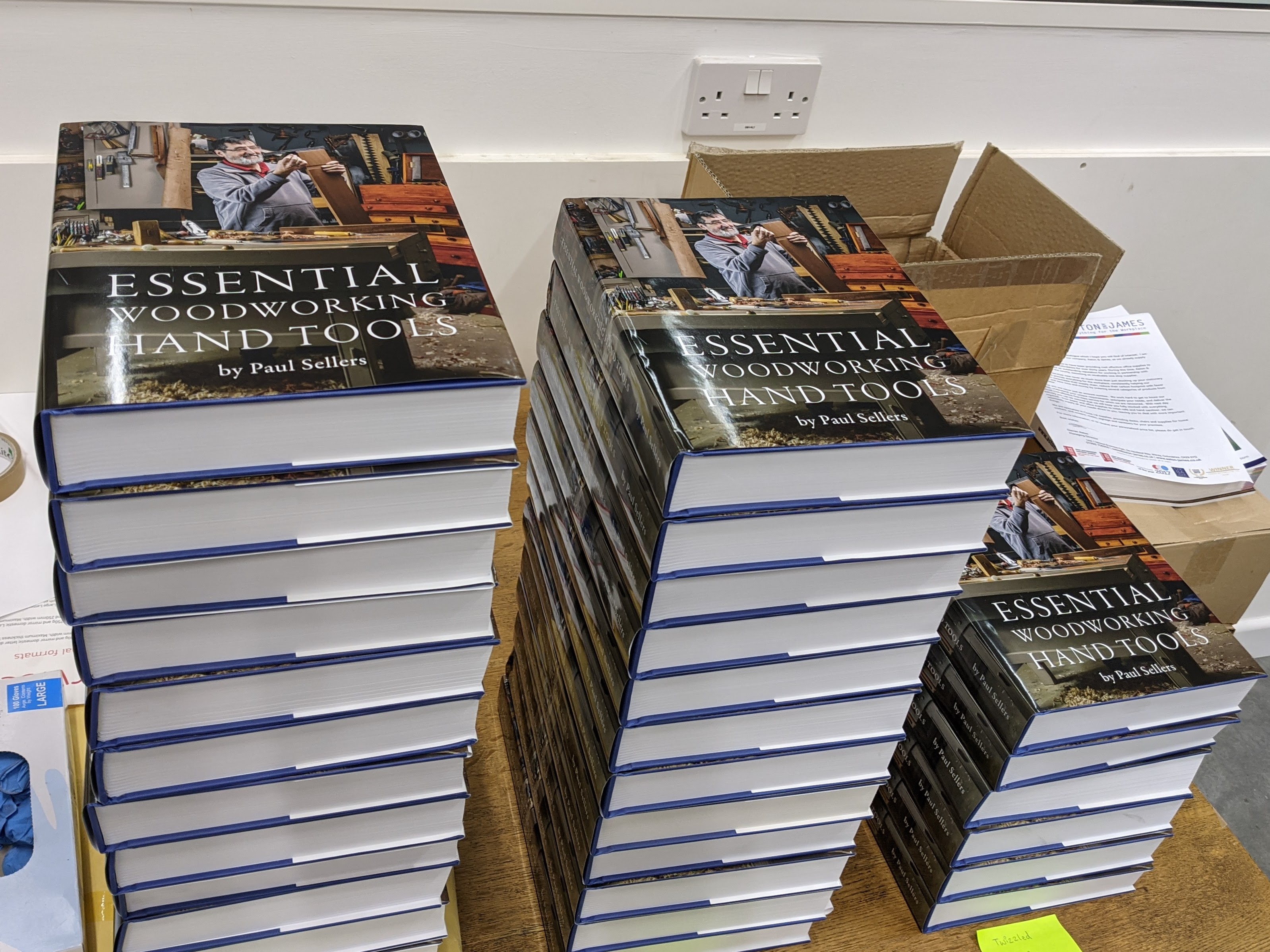

The reason I wrote my books, how-to booklets, blogs and magazine articles, started woodworking schools, created online classes in courses and took on a world full of woodworkers distracted by heavy machining methods was because I felt truly troubled that most of them just wanted a coffee table or a door and they fancied that they could probably make them if they had the right tools. Unfortunately, they considered the term tool to include space-hogging machinery. They simply didn't know that they could make everything they needed with just hand tools. For me, I didn't know I couldn't turn the tide with my theory of three joints and ten hand tools so I did it. There is no substitute for developing and owning real skills in woodworking. They can only enhance your life and the things you make along with self-satisfaction that can only be achieved by mastering what seemed at first to be impossible. It will cost you to get there, but the outcome is better physical and mental health, higher levels of fulfilment and more beyond you can have the kids with you in your workspace that has space for them. You can even listen to an LP without wearing ear phones that separate you from true corresponding with your work.

Therapies can come through various therapists, of course, they can and do, but, additionally, so many of you have written in and say that the best therapy you ever had was starting to work with wood. Therapy and professional support when done well is irreplaceable. We're not talking about that here as that is out of my realm altogether.

On my health. Well, I am doing fine but with age can come some symptoms we may not want. I am surprised I have got this far living virtually pain-free except for any injuries ranging from some deep and larger splinters, many more than average to two cracked vertebrae in February this year. Covid injections and a bout of actual covid didn't trouble me too much though I did have some shoulder aches after my first dose. I recently saw my chiropractor to deal with something I may have done to myself and maybe did not. Sometimes, 58 years of doing something one way can result in physical and mental harm. I've been a most fortunate man, my occupation took care of both. but though y hands still work great, I have something called a Dupuytren’s contracture, a disease that causes firm nodules which eventually appear in the ligaments just beneath the skin of the palm of the hand. In some cases, they extend to form cords that can prevent the finger from straightening completely.

I can no longer lay my left-hand flat on a table and sometimes it gets in the way; mostly I find no obstruction and though I have seen it slowly develop for the last 16 or so years; I have probably had it longer than that.

As for my being a long-term diabetic, my diabetes has caused me only minimal concern as according to my medical support my control is great even after so long a time of having it. This morning my self-test showed my blood sugar levels at 5.5.

I am a third-generation diabetic so supposedly it's in my genes. It has never stopped me from doing anything. I attribute this to my working physically and mentally too. Working and work ethic gives me great exercise every single day and my care with my diet helps me to manage my blood sugars really well. In general, I am pain-free almost all the time. Only when I exceed my body's capacity do I find an overstrain. I always try to work safely but I am not risk averse because I love doing things that push me. So, my chiropractor believes in DIY. After one visit he gave me proactive work to do on my own. I do the added work and things get better. He then follows up with a check-up to see how things are progressing. My greatest ever periods of long-term pain came from extended use working with machines. Since I stopped machining wood on that scale over 30 years ago I have recovered remarkable health. Currently, I am working on a leg pain from something I did but which concurs with a thinning of the cartilage in one of my knees. Who knows where this will go but planing and sawing and so on seems to have helped me. To have reached nearly 73 this far with almost zero pain and never anything permanent seems pretty wonderful to me.

Comments ()