Relaxing Your Future

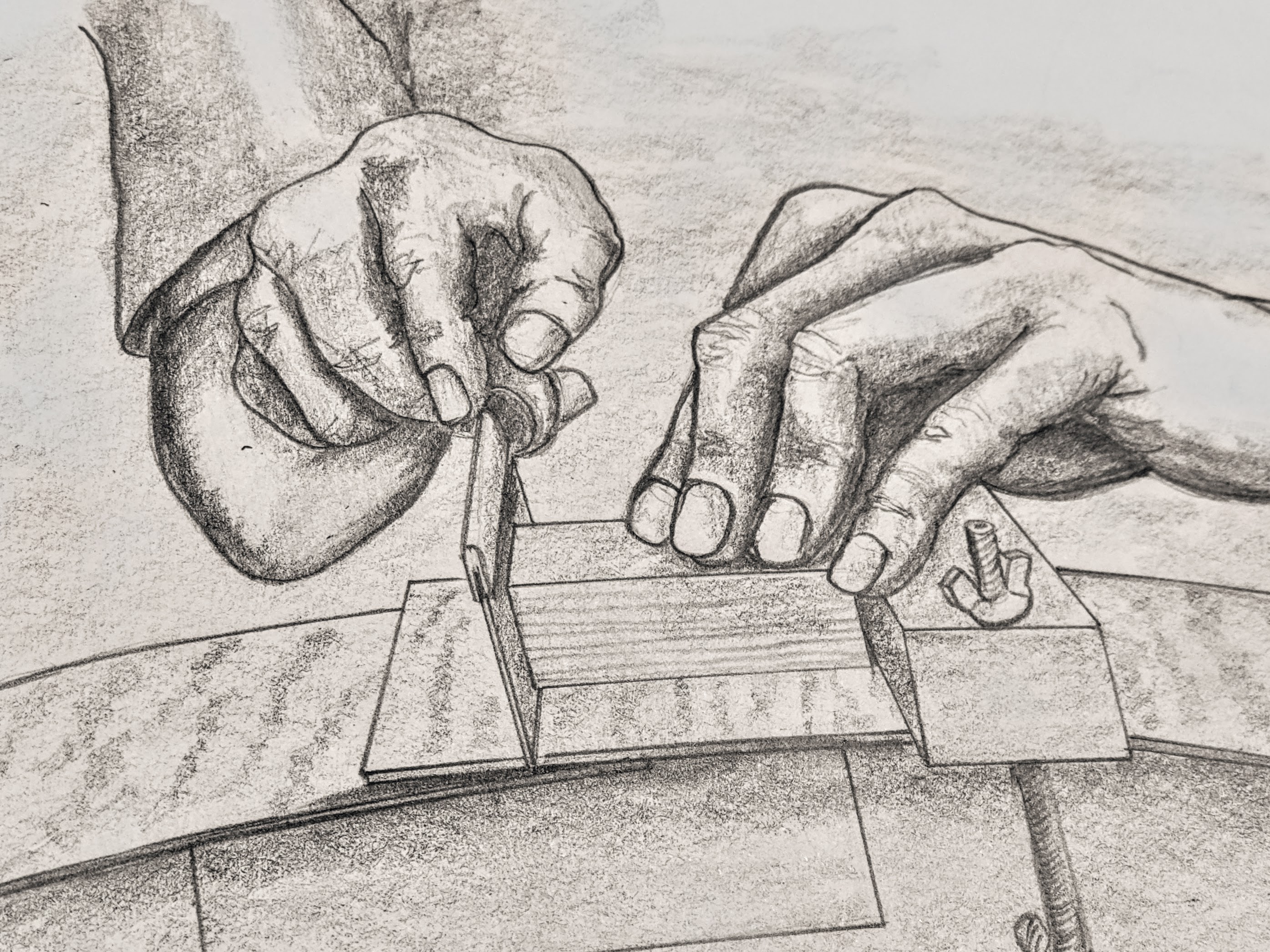

I relax into most of the cuts, let the weight of my arms and the tool work ahead of me. My task guides, adjusts after withdrawals from thrusting cuts readies reengagement cut on cut. Two hundred saw thrusts take but minutes with two hundred withdrawals matched equally in number and power. I realign and engage to push forward and cut more. I do this on and off throughout the days. Who can know the number of cuts in 58 years as a maker.

I dwell on the reductive process woodworking always follows. The start-work is the tree and the end result a thousand sections cut from its severed stem. Woodworkers new to hand tools seem often to have control issues they must one day resolve if they are to become what they want to be. Learning not to use force can be hard. The very thing that causes a saw to curve from the line is often excessive force yet they believe ot takes force to effect each stroke to follow a line. They apply more force as the drift progresses away from the line: the last thing my woodworking needs any of.

Patience to can be lacking. Instead of enjoying the cut's stroke on stroke passage into the wood they somehow want it to be over. They see progress amiss when progress equals faster speed and distance. Adding force and speed to them seems a good answer. Side by side they take twice as long as the experienced man who's mastered the craft and accepts every process as a form of meditative multidimensional engagement. On the one side, there seems great peace in the work, on the other a frenetic disconnect. George's voice comes low and calm, an even influence to roll in with its stilling metre (meter USA) each time I see a person using excessive force at higher speed that disallows the peace of accuracy and thoughtfulness. This is my foundation stone of truth. Craft, all craft, relies on this truth to undergird all that they do.

When George taught me to saw and plane I listened with a heart of care. This too is a bedrock. It seemed unnatural to me not to have a full-fisted grip and to point my forefinger on the tools, but I listened and followed instruction until I owned it. Many years later I saw the universality of his instruction. Those I met from or on different continents pointed the forefinger and passed only three fingers through the handle. The uninformed never do. This showed the pure power of word-of-mouth, passing the methods on to future artisans. For me, it proved a remarkable man-to-boy transfer of craft. It's not gender specific, I only know one woman woodworker well enough to consider. I never see women in woodworking even though its a craft there to be readily had.

Relaxing and easing into the cuts is a different and separate issue even though the two seem connected by the task. Defining the power of the saw hold as less of a fisted grab and more of a firm grip only tells us how the hand engages the saw with a type of accuracy that translates into both accuracy of cut alignment and then too pressures according to feedback from the wood through the tools as they perform their cuts. These things are not written of. To deny the writing of them and the speaking of them is to deny or at least perhaps fail a next generation by undiscussed detail. Relaxing in the cuts is a more difficult consideration and concept to convey because the watcher cannot see how the hand, body and brain are working and what energy is being expended in terms of effort and direction. The relaxed hand moves a saw that more simply encourages the saw into and through each cut but the relaxed hand in no way means a limp hand There should still be a firmness in the same way we lift an unhandled glass to drink from or lift a small child to our shoulders. My confident cuts can be mistakenly translated by others in the minds as something fast and strong with rapidly repeated manoeuvres. In reality, it's quite simply the expressed confidence that comes with any mastery that requires repeated moves in succession; any expert always delivers his hand work accurately and with delivery. I don't ever use my tools for speed. I simply do it quickly because early on in any task at the bench I always establish a rhythm that matches my body and that then establishes synchronised power in a measured and controllable way.

As a young man in my apprenticeship, I watched men without a square cross-cut wood dead square in both directions and time and time again. They were relaxed about it, expected squareness and it always seemed quite effortless. They were working in two realms -- effort expended and accuracy. These two elements always worked in tandem. No one used a Skilsaw with a speed-square. They were on their way but had not yet arrived. The speed square replaced the intuitive and the electric power the energy. Line up the Skilsaw to the edge of the speed-square, press the trigger and gentle, steady push-feed the saw through. Fast cuts using either method resulted in a coarser end-grain tearing. Just less neatness. In framing out two of my homes when living in the US and then adding additions too, I generally relied on the Skilsaw and the speed-square. Not for everything, just mostly. One method is just about effortless, the other wholly engaging and high demand. Both have their place.

So now I come to a point. Chop saws have very much replaced the Skilsaw and the radial arm saw for most cross-grain cuts but cannot be used for most large sheet materials because of certain limits in reach. No one machine fits all in the same way no one handsaw fits all. To try to compare the two realms is near futile. The hand toolist gets on well enough with about three saws costing £60 for the three via eBay. The machinist will need, well, many times that and it doesn't end there.

Why this? Hmm!

In my emerged world, life and work is about the composition and integration of both. This is not something most people experience, recognise or even want or can do. In my world, work is the most welcome part of my life and I think that this results from not having to wear an office, the complimentary suit or uniform or the commute: all that I do fits and suits my existing or self-created surroundings, my environment, the greater whole of people I know and care for. I try not to slip in a bum note to my life or the lives of others just on a whim, though mistakes and the unexpected can and do happen. Composition is about consideration, adjustment and the order of all things. Some things rely on minute-by-minute decisions, others are part of a longer term plan. Day-to-day writing is composition of thought, I write many times a day and then too I make all day in tandem with writing. At other times I factor into a day time to work on a book that discounts too much intrusion or interaction. By this I can compose both myself, my day and my working. I set realistic goals for myself and usually work to them. This is order. Without goals, we achieve only sparodic and mild success, we rarely achieve what we do with some preset goals. The goals don't have to be rigid legalisms, just self disciplined. Through recent decades, I have striven to recompose and regenerate my life differently. By doing that, others too have nudged their own lives and worked to define and rework theirs. I think we are probably talking a few hundred thousand here. The simple act of building a shed for woodworking, gathering a few tools for them becomes a part of recomposing who they are or want to become. Sweeping the shavings from the workbench and the floor gives opportunity for thoughtful planning of the next task -- this too is composition. Simply standing in the middle of a shop in some ephemeral condition is not usually as fruitful as when your cleaning and clearing in the physical. That's my experience at least. In simple tasks we somehow release ourselves to compose, plan and prepare things future -- this too is active composition!

Emerging is a part of the process by which we become conditioned and trained to take our part in the future and the power of culture changes and transforms us to become compliant to the status quo. This tends to be more a conforming rather than a composition. A major wonder in all of life is the composition of every element of life. Aristotle coined the phase "Nature abhors a vacuum." Science may well have proved there to be exceptions to that rule but as a maxim for living it is true that the phrase simply expresses the idea that unfilled spaces go against the laws of nature and physics and in our world as designers and makers every space needs filling with ideas first and then the making of ideas according to our ideas. This is composition.

It was my parents and George who encouraged me to take total responsibility for my life. This translates into self

Comments ()