In the Beginning . . .

. . . the summer heat beat down and the earth beat back up.

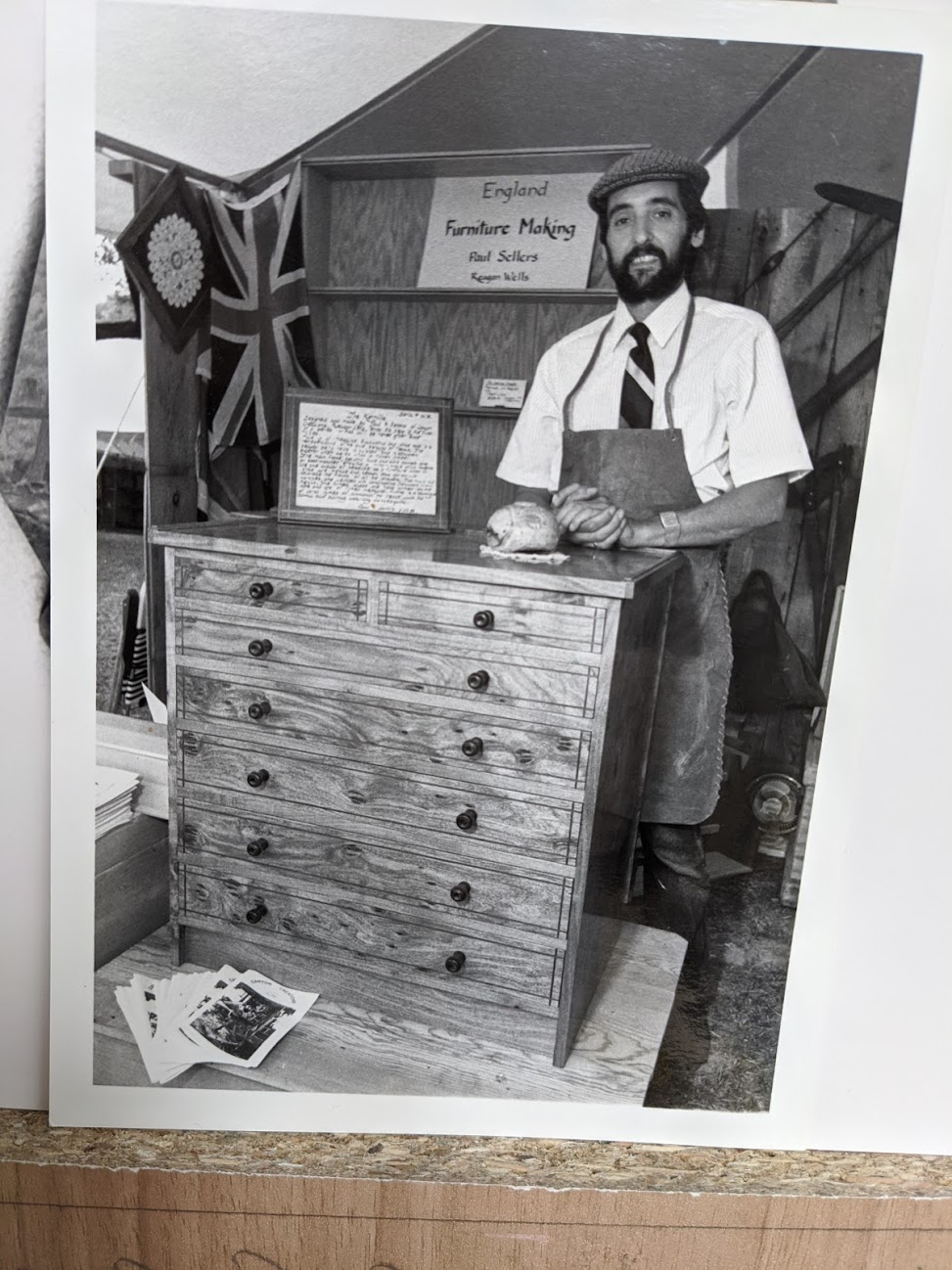

August, September, where the sun beats down heavily with increasing power and from the weeks and months before the earth radiates relentlessly back long after the day's end. Relief comes only beneath the live oak's outspread umbrella and from floating the Rio Frio or the Guadalupe in a truck tube. Even so, still, be prepared to fry. Shade overhead helps but earth radiating from a Texas summer sun seems never-ending. There's the build-up you see. Each day sees an increase. In Fahrenheit we're around 109º, that's around 42º Celcius give or take. I'm at the annual Texas State Fair in Kerrville beneath a cedar-covered brush arbor, US spelling, arbour, UK and Canada. It's 4 pm and there is no escaping the heat. The brush arbor works to shade from above but the earth is another matter. The Texas Arts and Crafts Foundation developed this year's theme to replicate settlers moving west as tradesmen and women filled with the hope of settling and setting up temporary workplaces to practise and ply their wares as they passed. I'm the resident furniture maker newly arrived from my native England (not far from the truth). I am to establish myself as a furniture maker in the Hill Country of Texas. The local towns are a mix of small cowboy towns, German settlements, people claiming new life on a new continent. I have just about set up the workshop to my liking, tools, wood, workbench. I'm feeling a buzz. I have some of my newly made furniture pieces around me. Unusual styles for the Texas audience but mesquite has the draw. Nobody l knew mesquite could be so "Purdy!".

It wasn't easy for me there in Texas, starting up from nothing. The thing that made it work for me was the kind ways most of the local Texans extended to me. Chillie cook-offs somewhere along the canyon in someone's back yard of a thousand acres where a realtor lands his Cessna on a sandy runway after his commute to Houston and business. They could be tough, maybe a little rough around the edges in some, but their openness and kindness were unsurpassed, that's in my experience at least. But the sales of a couple of pieces at the show really helped cover a few bills. My home workshop and home were 32 miles from the nearest town and 16 miles into the dead-end Frio canyon. You drove through five low river crossings to get there and halfway in you thought you had taken the wrong road. It was quiet and peaceful and much nicer and friendlier than Manchester, England. Every few hours a small plane would buzz across the sky one way or another. I'd look up and wonder who he was and where he was going. Wonder what he could see from up there.

At the close of my long weekend demonstrating and talking to people, just before the show closedown, Audie Hamilton, the show director asked if I would teach a woodworking workshop for them. At first, I thought, No, but I relented and said OK. The upshot was that this single event back in 1990 would be the springboard that launched me towards the international outreach we now have. Who would have thought? The rest is history and history it may be, but it was from this that I began to think more closely about the future of woodworking as a craft. What did it now mean and what did it matter if it died? The writing for me was clearly on the wall. The only woodworkers I ever met in the previous few years never used any hand tools. If it didn't come off a rotary cut it didn't get used. In teaching students how to slice out a dovetail with saw strokes and chisels the ingredient for success started to gestate. What was that? Simple. It was having a burden!

At the fair, the men gathered around the bench two deep and full length and around both ends. Each demonstration throughout the day it was the same. I made dovetails in a couple of minutes sometimes and at others took more time. Housing dadoes came the same way and then moulded frames with a vintage moulding plane 150 years old. The banter back and forth was tinged with a humour only Texans can carry and you have to grow into and with it to understand. The days passed quickly and though tired at the end of each day I was sorry the days ended.

Preparing for the first teaching I ever did took a few weeks. As a collector user, I had enough for ten students and kept the class simple. Unbeknownst to me, what I put together back then would undergird my future belief and that was that with three joints and ten hand tools you could make just about anything from wood. I am so glad that I worked from the experience I knew worked and had worked for me for a couple of decades then. I never copied other woodworkers, teachers or existing schools. Simply put, I made the three joints and put the tools aside as I used them. That gave me the cluster I have used throughout my teaching. It was from this that I came to ultimately write my much-needed second book, Essential Woodworking Hand Tools. There is a story in that too. Perhaps I will get to it later.

The three-legged stool above came from eight hand tools. They can all be used throughout woodworking. Of course, ten hand tools were pretty minimalist, thirty would be nearer meeting the needs of we woodworkers. The idea of course was to help others to understand what the real and true needs really are and that you don't need say a #6,#7 or #8 bench planes, a #4 and possibly a #5 will take care of almost everything when you master the skills. Yes, others are nice to have as and when you come across them or you can afford them. No need for a £120 coping saw when a £5 secondhand Eclipse works perfectly well. Even cheapo chisels are not like the imports of old in the 1960s when they inevitably snapped in two under the slightest pressure. That said, the only chisel I ever had snap was a UK-made premium chisel. Probably just a lone bad one but still offputting enough. I think the days when you said imports of cheapos are no good are gone. You can buy a set of four chisels that will take and hold a keen edge acceptably well for around ten pounds or dollars. The handles may be a tad small, the finishes a bit rough, but they will cut dovetails for a year or two to get you started. I have cited the #4 as the only true essential plane for woodworkers if they must choose. It's not the actual plane but the width and length of it. A couple of inches wide and around 9" long is what we call a smoothing plane. With this, you can prep stock for joinery, true up surfaces for finishing and trim off any amount you need to. Heavy set people might go for the wider #4 1/2 and though a #4 will well suit most of those of us of average size, the #3 is a good choice for those of a slighter build. For a one-size-fits-all plane, the #4 does it. If I had no other bench plane the #4 would suit me the best. You should be able to pick up a #4 Stanley or Record for around £20-30. It will last you a lifetime of daily use, no question about it.

As I set up for the workshop I found myself outdoors under a newly raised brush arbor at the back of an outdoor sports stadium. They thought it would add interest to recreate the pioneer spirit for the student and it worked surprisingly well to conjure up that same spirit of adventure. As I laid out the tools at 7 am I felt excited. Who would come? Men, women, professionals, older children? I had no idea. As I ran through the tools, touched the cutting edges, and placed them as a set per person, my mind ran riot thinking about what it must feel like for the attendees. At 8 am they all stood around the bench and introduced themselves, giving a brief overview of why they'd come and then too what their expectations were. The men dressed the part a little more than the women. That was mainly because their exposure was likely longer term and they had the edge. In actuality, the men kind of overdressed with an image they thought to be of a working carpenter if you will. Side pockets now called cargo pants and suspenders (braces UK). A bandana around their necks or heads, that kind of thing. Even a red handkerchief floaty dangling from a back pocket here and there seemed to complete the outfit. I get it. But there was a woman there who made a statement that really stuck with me. " I truly hope I don't make a fool of myself in front of you guys. I have always wanted to learn woodworking from a skilled craftsman and here I am. Be patient with me 'cos I'm a slow learner doing something I was never allowed to do!" She looked to be about 60. I felt sad in the truth of it. I'd heard this many times from women who wanted to do woodworking but never could. That she had had to wait so long for something that is very much a non-gender specific class remains even now. Ingrained expectations and attitudes that seem never to change very much a all. I was glad to be the bridge for all these people. Having the right tools and insights was a freeing experience for us all.

Slicing into the wood, a sharp saw held a gaze in a mesmerising way. Chisels sharpened keenly gave them cuts they never dreamed possible, a totally new concept yet one they suddenly saw as essential. I explained that the true accuracy of all things craft revolved around the sharpness of the tools they would use and then too the engagement of their physical bodies applying precise pressures and direction. Peeling off shavings with planes one after the other slowly came and this seemed the most conclusive insight as to exactly what sharpness was. As we closed out the day, each one of them took their three joints along with practice pieces, the scraps from the joints and even the shavings. Such small things speak volumes of overcoming doubts and fears. We should never despise the days when small things become universally big. Men flew and walked on the moon only two decades before. This for them was their moon landing, surely.

This, my friends, was the spark that lit the fire to my life becoming the maker teacher I never thought to become. I didn't do it to create a business because I couldn't make it as a maker I did it because I had a burden for my craft. A constant flame began and it took only a year or two before I was able to begin a full-time woodworking school in central Texas. I continued furniture making as part of my income-producing life all the way through from that day until 2008/9 when the last US pieces I made would be the ones I designed for the Cabinet Room of the White House. That passage saw the start of establishing the first woodworking school in Texas and many surroundings states too. Back then there were only a handful of schools in the whole of the US. It was from this raw beginning that I began to write magazine articles, the woodworking curriculum I would use for three decades to date, and go on to write books, articles and how-to booklets. Today we have provided thousands of hours of video content to replicate everything I ever taught one-to-one in classes. The craft of hand working in wood is more alive today than it would have been without that beginning class at the state fair. Those were the years of the greatest demise when machining would was king. In that day there was almost no hand tool woodworking to be seen anywhere. Not so today.

Comments ()