Tool Sharpness. . .

. . . depends on your regularity. It's often a regularity that woodworkers most generally neglect. In fact, tool sharpness reflects who you are. As an apprentice, George said sharply across the bench, "Sharpen up and don't be lazy!" As an adult, such things are unsaid to you. Or are they? Does not a still small voice nearby, inside you, say, "Sharpen up!" from time to time? And do we not equally often ignore the prompt for a while longer than we should? We go until the saw's stroke strains and the plane's swipe resists to confront our energy in faltering stammers and we feel, well, more exhausted and frustrated than we should. Simply put, we rarely sharpen up enough and yet sharpness is key to the well-being resulting from our work, in our psyche and other elements of our health. The simplicity of self-discipline wrought through simple acts in workmanship, sharpening, for instance, changes the energy of output and dynamism of working the tools and wood as they should be worked. George and all of the other men would often ask me if I would just "Touch up the saw for me will you, Paul?" and I would take a saw file and file the teeth of their tenon saws with a single stroke through each gullet even though I might have done it only a week or so before. Touching up the cutting edges and saw tips of their tools was an ever-important part of their daily self-discipline. For the older men suffering from the poorer healthcare in the war and then the postwar era, poor eyesight had made saw sharpening more difficult for them. Eyesight and arthritis, hand tremor and steadiness resulted in elderly disabilities before their time. They didn't want to be seen as less abled than the younger men. A sharp saw made all the difference.

Just when to sharpen is more often delayed than resolved as 'a stitch in time.' Our own dullness and inability to gauge just how far the edges and tips have gone beyond their sharpness usually results from procrastination, but by pushing the tools too far we lose the critical edge that separates waste from the wanted as an infinite edge and then too the perfection that sets our work apart. In woodworking with hand tools, sharp edge tools and saws are critical. If you are not prepared to sharpen up every day and then throughout the day you should give up on hand work. Sharpness gives everything we do the crispness we need and without it we forfeit what we could and should have in our output. Most often we do it an hour or two later than we should and the evidence is clearly reflected in the shoulder's corner line or the face of the wood we just worked. The result of dull saws, any kind, may not be quite so evident at first glance, but looking a little more closely will tell the truth of our laziness. But of course, it may well be that we actually don't know what we are looking for or what to expect. It may also be that we don't realise how little it takes to 'touch-up' those saw teeth. A single, half-length pass with a file once every few hours of use might well be all that we need to restore complete crispness to the edges of those teeth so that any severed fibres give us the perfect precision on the surface fibres. Pushing a tool beyond its limit is how we craftsmen and craftswomen work. I've said this before and I will no doubt be saying it again and again, "Sharpen up!" Here is a success though; I never have to tell John and Hannah to 'Sharpen up!' This, to me, is maturity!

I bought a #4 plane for my granddaughter recently. It was an especially nice one that she could work with when she is old enough to use one herself. I doubt that that is too far off. She comes into the workshop most weeks to be with me for a while and helps me to sweep up and bag shavings. She also uses her spokeshave fairly regularly, knows what it's called and where it lives in her toolbox by mine. I think that she is due for some more wood bonding time all the more. I noticed that the plane I bought had only been minimally used before my eBay delivery. The blade is full length and had evidently been sharpened but the rest of the tool showed no signs of real wear. As it is with many tools bought online, when the tool lost its sharp, usable edge, the user continued until the cutting edge was completely rounded over and could no longer be forced even by the most powerful but dulled muscling. We will sharpen it together when the time comes.

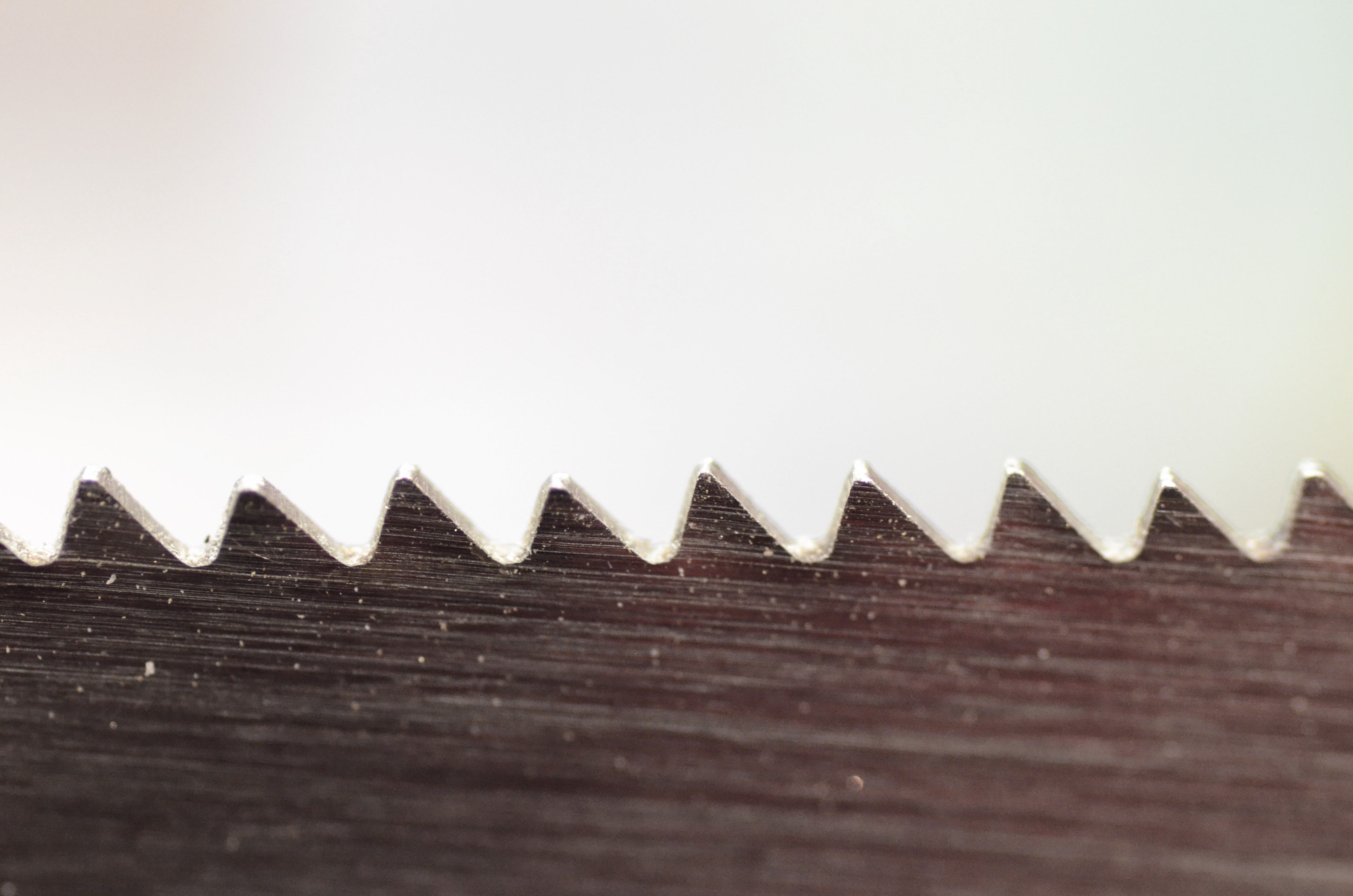

I want to talk about saw teeth' sharpness and why we should sharpen them more often than we might actually see. I hope that I can persuade you to sharpen as needed and not as wanted. Rarely do we see saw teeth for what they are. The pictures below are of rip-cut saw teeth.

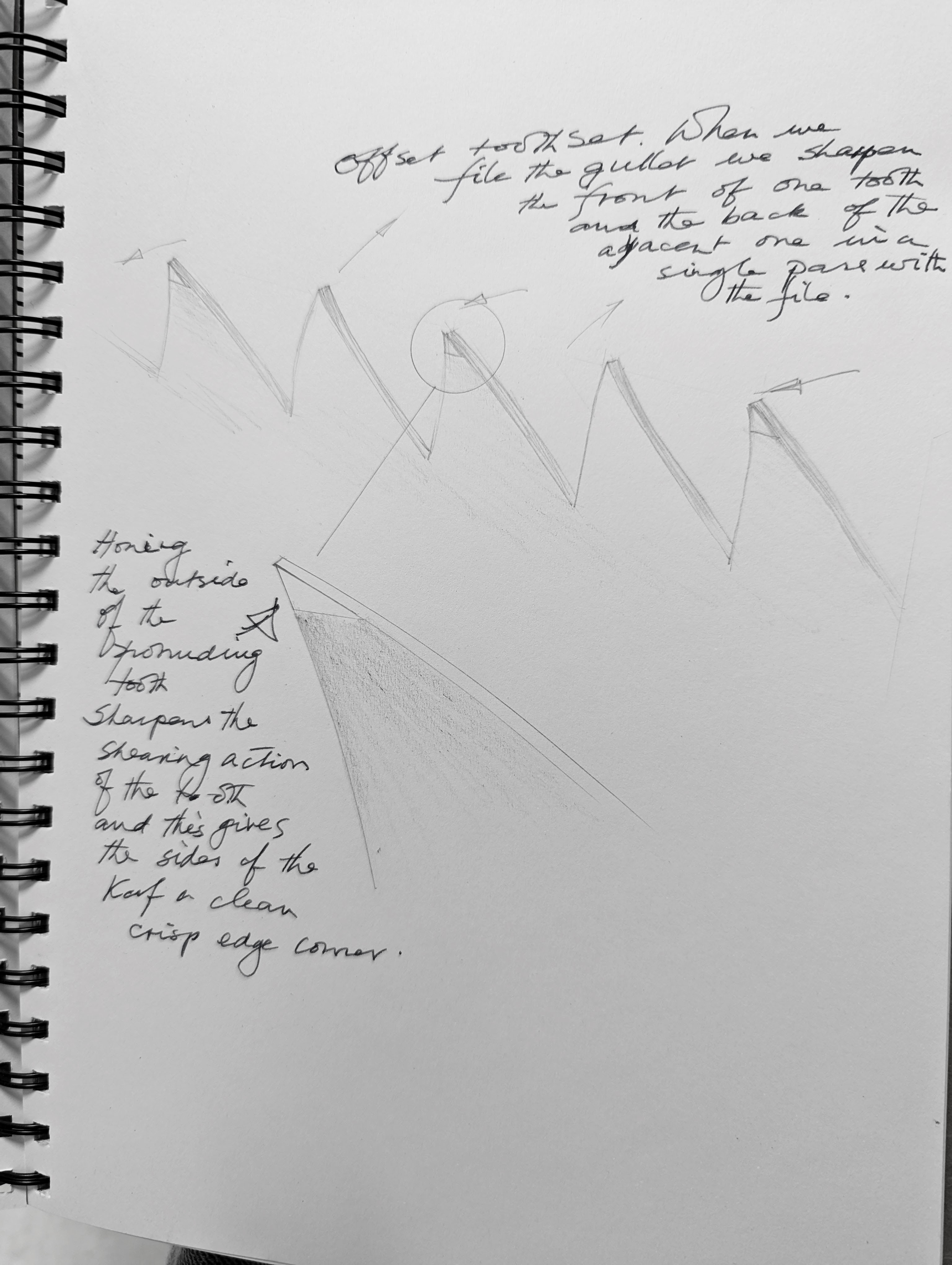

That's what I use in 95% of my woodworking as these are the saw teeth we use the most in joint making. Dovetails and tenons are mostly rip-cuts along or with the grain. Small rip-cut teeth saws work perfectly well for both rip cutting and crosscutting wood in joint making and even on shoulder lines. But the saws must be sharp and repeatedly sharpened. Ripcut saws have four sides to the teeth but use only three sides of the teeth to engage in cutting the wood. The offsetting of saw teeth with set negates the insides of the teeth from actually cutting. The chisel edge cuts the face of the wood, but the outsides of every tooth shear-cut the two sides in the kerf itself. The part of the saw tooth that wears the fastest, therefore, is the outside corner of the tooth. And it's this that needs restoring the most. To restore the crispness of this outside corner means sharpening the two main facets plus a little surface honing of the outside faces of the teeth. Honing the outside faces refines the cutting edge at the pinnacle point or corner where the three sides to the teeth meet. It's a small step that makes all the difference to our western saws. For cutting two-by-fours in construction, we don't need this. For dovetails and other joints with crosscut edges, we do.

If I can persuade you that the actual chisel edge is marginally less important than the outside third face of the saw then I have succeeded. The business edge of the saw is indeed the chisel edge. Don't get me wrong, but no one I have ever known has talked about the third face with any degree of importance so I'm doing it here. You have to understand that we force each alternative tooth into a slight bend to create set. The very exposed corner in an exaggerated picture shows how little support there is for that specific corner to each tooth. It makes sense then to say that this corner is the most fractious and the one that breaks off the most readily. One small step takes care of this and increases the quality of the cut and also the longevity of the working capability of the saw teeth.

After setting the teeth, I add masking tape alongside the saw teeth. Depending on how much set I want, I add one, two or three layers of masking tape to increase thickness. I then take a diamond hone or a sharp flat file and use the tape as a registration face to run my hone or file along to keep the cutting face of the tool parallel to the saw plate. This then further refines the cutting quality of the tooth. I don't need to do this every time I sharpen, perhaps every two or three times, that's all. It's this that gives my housing dadoes and shoulder lines the crispness I always strive for and it also enables me to go deep down into the cut with less or any need for pare cutting with a chisel after the saw cut is done.

Comments ()