BedRock or Bailey-Pattern throat openings

My task in reviewing issues woodworking is mostly met very favourably. There is more to my reviewing things than simply looking at things critically, that's less than helpful, searching through texts for truth though often reveals the attitudes of makers as much by what they miss out as what they say. I think it's true to say that manufacturers on a global scale mostly make tools and equipment to sell and never to use. An engineer stumbles across something that could be made better, gives it some thought and, hey, he makes the thing better. Equally so, many a good maker has been put out of business by a manufacturer cutting costs and offering something lesser but looking the same at a lower price. Vises would be a good example. Record vises of old, quick-release ones, could never be beaten. The company was taken over, the vises were dropped and Indian and Chinese imports were brought into the market to replace them. The quality has never been the same since. A mix of manufacturing/marketing strategies came into play. Distributors would pay only this or that price and the makers made accordingly. Vises have never been the same since.

My advantage through the decades has been that I not only used but used as a full-time furniture maker and woodworker earning my living and supporting a family from a single income. That's what I've done through a complete lifetime to date though my kids have long since flown the coup. This alone gives me a different perspective than others. Additionally, I don't sell tools, take tools or equipment as a kickback and neither do I take any sponsorship. I'm my own man. Doubling or tripling my income for almost no extra effort is of no interest to me. I want clean output.

In my work, I frequently encounter ambiguous statements, untruths, and meaningless statements further cloud the truth with confusion and many an imposter counters truth on many levels; even reputable makers toss out statements. One famed sawmaker in Sheffield once told me that the Philadelphia Disston saws were made in Sheffield. In a culture of increasing falsity, we face the output of opinions that are nothing more than that. Opinions tell us that pull-strokes are better than push-strokes, bevel-ups are better than bevel-downs and harder steels are better than marginally softer ones for longevity but then not for resharpening. Such opinions, mostly non-factual, usually cause many to never determine for themselves what they prefer even though they may never have given both the same fair period of trial over a number of weeks and months. When we have more open minds, consider all things as possible, practical and practicable, we find that creative people in both realms can make most tools work and get used to them anyway. They can ultimately be used to give exemplary levels of workmanship and we should all remember that the finest work in the history of world woodworking was achieved centuries and even millennia before our present age except in the most exceptional of individuals. Thirty years ago, a Spear & Jackson catalogue advertised two classes of saw with descriptions I had never seen before. One description said, "Lasts five times longer than conventional saws." This was in reference to their plastic-handled impulse-hardened handsaws. The second description described a wooden-handled handsaw as, "Resharpenable." a term never used before that date because everyone assumed the saw would need resharpening periodically as part of general saw maintenance. In the first description, it did not tell you that that saw could not be resharpened; that it was indeed a throwaway saw. Within a couple of years, the resharpenable saw was no longer sold and for a couple of decades, it was abandoned as a marketable product. I'm not sure what made the difference. I do think I had a major part to play in restoring the use of handsaws to woodworkers by filling in the knowledge gap, of sharpening, setting, profiling teeth to task and so on, yes, but also my advocacy for lifestyle woodworking and the restoration of hand tools and techniques to woodworkers on a worldwide scale. My advocacy for the way we work being more significant when skills are pursued as a way of life has become all the more important. I plan to spend my remaining years researching and teaching as much as I can, as well as videoing and writing more books, manuals and of course my articles too. I want to leave the legacy I began working on 30 years ago. I have an amazing group of people around me every day testing out theories, writing, drawing, photographing and collating all the information. We have a massive archive to back up what we do and to challenge our theories too. What cannot be challenged is the validity of physical work with your hands, mind and body. Without working with my hands and my hand tools I would be amongst the most depressed and the most redundant. My output reaches hundreds of thousands of creative minds and keeps expanding when 30 years ago hand tool woodworking was all but gone. Imagine!

The Narrowing Down of Plane Throats

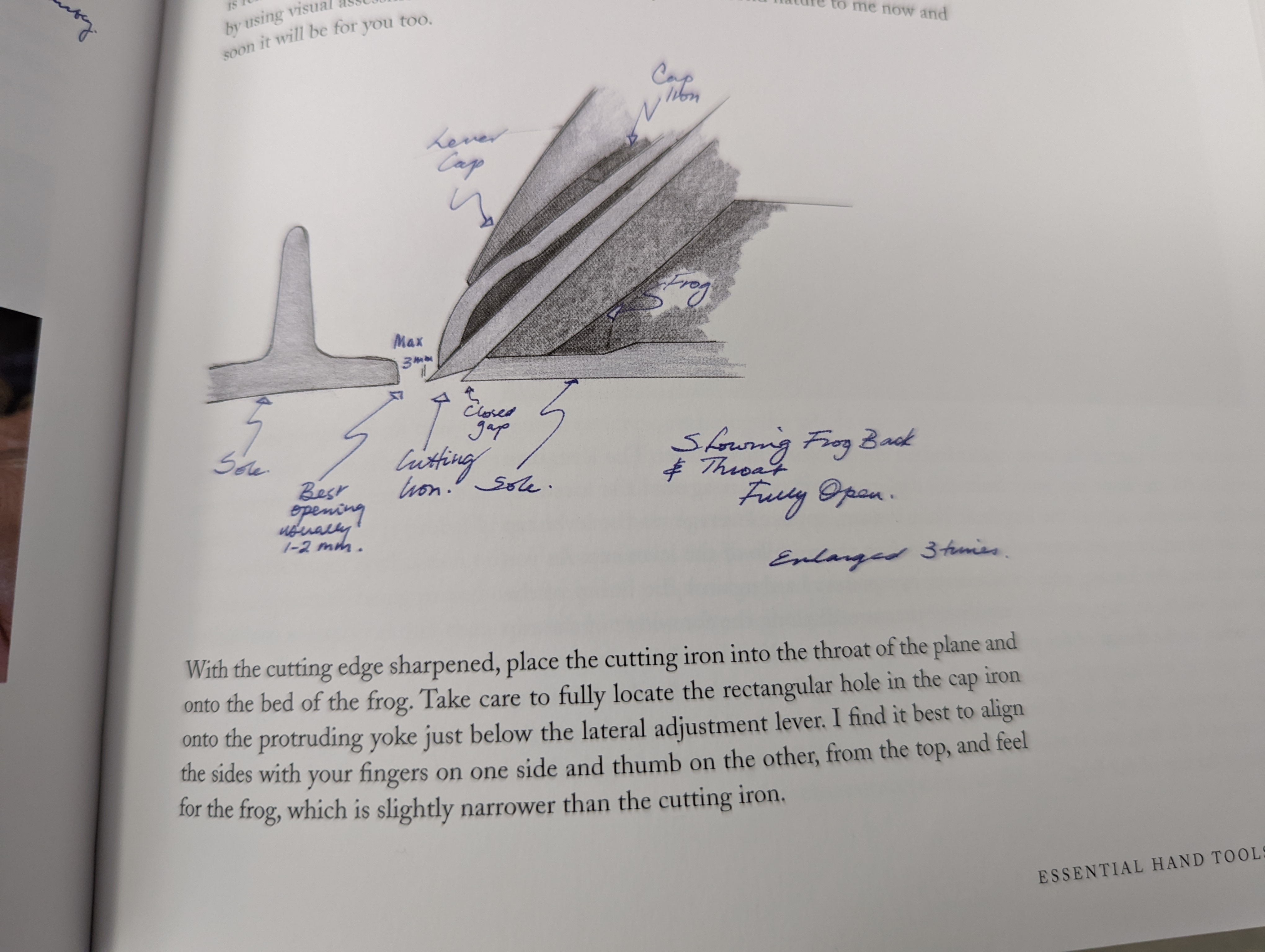

Some introductions are necessarily longer and I make no apologies for this one being so. The following article is also partially covered in my book Essential Woodworking Hand Tools, but my research, use of and concern for the all-metal, metal-cast planes have taken me deeper. Having spoken of it and demonstrated it for many years, some things are worth saying and even saying twice and thrice. Perhaps planes with narrowable throat openings have improved our lot. I doubt it for the main part and so `i find it more questionable than practical. Other gurus through the years have given the impression that we professionals are always adjusting the throat openings of our bench planes. We're not, we never were and most likely we never will be. Looking at it practically from my personal long-time exposure in different woodworking trades and then through my own research into past centuries, nothing has changed except the sources of information. Adjustable throat opening adjustability seems to be more unneeded than advocated, for the main part. Its benefit option really affects our plane work in the most minimal of ways and yet so many these days espouse the benefit as more essential to good plane work (especially from tool salespeople looking for extra spin to confuse with). Vintage wooden planes used in bygone eras throughout a variety of woodworking crafts had no such option. I suggest that one in a thousand or ten thousand of crafting artisans might well have owned a plane with a special setting of a narrowed-down throat opening but in the day-to-day, it was more practical and useful to have 2-3mm openings. In other words, not closed down at all, ever. Take any new old stock wooden plane and the throat opening will be at its narrowest. Gradually, through use and an occasional truing of the plane sole itself, etc the opening naturally gets larger year on year. In many cases, the throat is narrowed down again by adding a wooden insert to the sole in front of the mouth opening. In practical ways, the throat opening on most planes can remain the same for decades and your work will always come good.

As it has become with all things woodworking, what was always really quite simple has now become more confusingly complex by information overload. Why do I say that? Mostly it has become so because trades handed down from crafting artisan to apprentice no longer exists and ceased decades ago. Standing at the bench, sharpening a saw or a chisel, setting up a plane or learning to saw straight was monitored by an experienced man or indeed many men. That mentoring capacity preserved the art of many crafts for millennia. It has never been replaced. Now we face opposition from many opinions that serve mostly to confuse. Sharpening does not need micro-bevels and bevel-up planes can cause many, many more issues than they resolve there at the workbench. It's possibly nice to own an alternative type, but far from essential. These are simple facts you get to know through experience and not merely an opinion of picking up a plane and using it for a short time. I've said it before and I will say it now, the tool you end up preferring will be the one you pick out and pick up the most when you need it. That said, there is nothing wrong with owning a nice this or an adjustable that.

Do We Need an Adjustable Plane Throat?

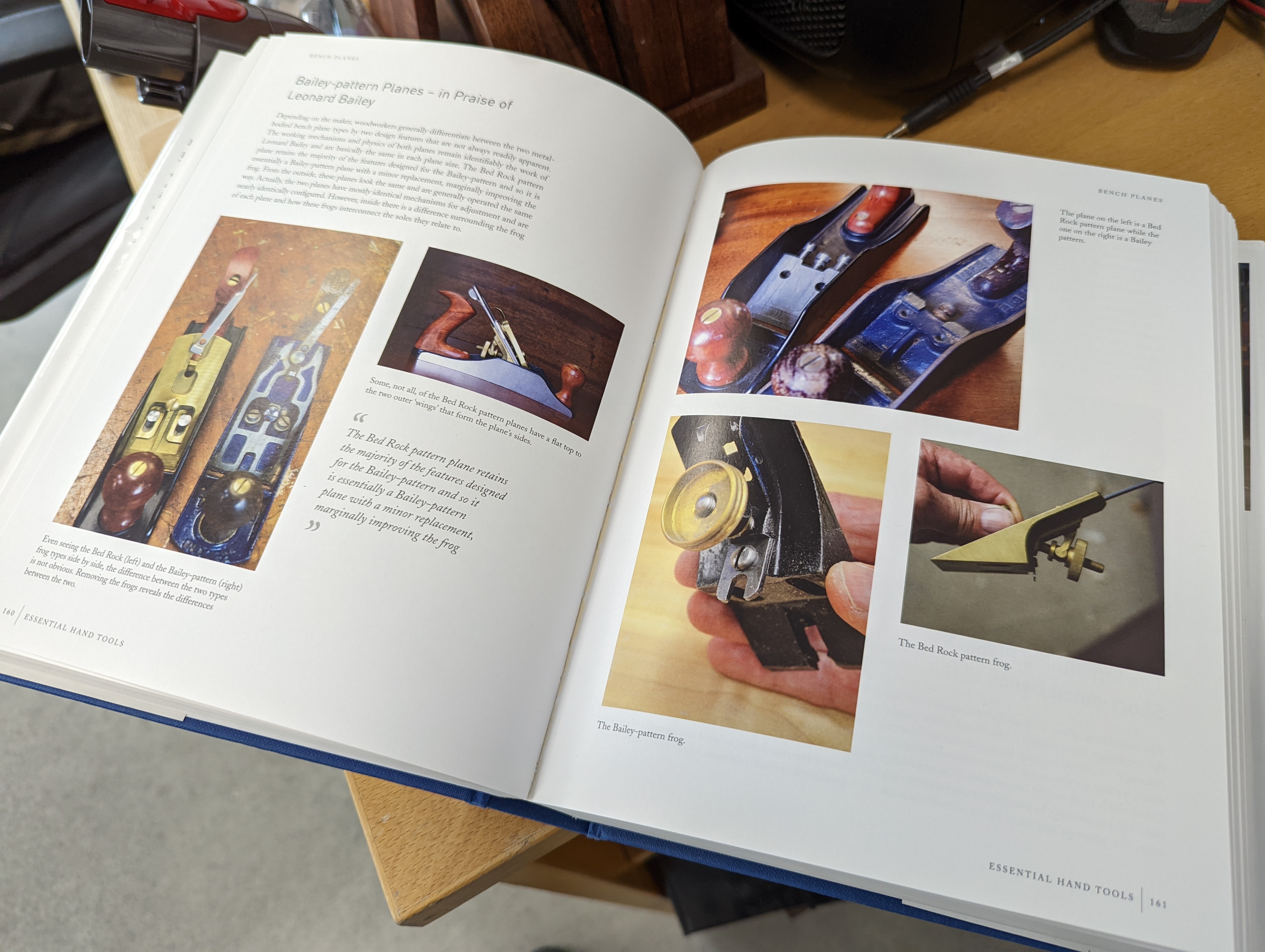

Basically, this question only came into being when the option was offered with the introduction of the Bailey-pattern bench planes in the latter part of the 1860s. But the question has come up again in more recent history with the reintroduction of the once generally rejected Bedrock version of Stanley planes. Before then, in metal and wood versions, all planes had fixed throat openings and any that were indeed changeable were rarely changed if ever anyway. Stanley Rule & Level ended up owning and manufacturing the Leonard Bailey-pattern bench plane types and subsequent to that the Stanley BedRock-pattern bench planes, which have gained modest popularity and favour over the last three decades but not because of the adjustability of the throat but for the quality of engineering standards. Both plane types have been produced as knock-offs of the Stanley makes by entities such as Clifton, Quang Sheng, Juumma, Lie Nielsen and Woodriver, all of which acknowledge these planes as original Stanley BedRock designs somewhere in their information. Makers in the USA, Mexico, Asia, England and Germany have all had production facilities copying both Stanley versions of the plane under various names when Stanley's patents ran out. No maker in any of those countries came up with anything new and significant much beyond a changed alloy. But all of them did offer tighter engineering tolerances and thicker, heavier metals resulting in heavier planes. I say this solely to say that that is just how good the Leonard Bailey designs were in giving us one of the most formidable hand plane designs in the Bailey-pattern planes ever invented.

The difference between the Leonard Bailey-pattern plane and the BedRock version lies only in the way the frog is designed, installed and retained. The frog in these two plane types is an angled block of metal designed to elevate the cutting iron to an angle (the bed angle) of around 45º and which is anchored by twin setscrews to the main body and sole of the plane sole. That said, the two plane types have two different systems of anchorage. The BedRock version is cleverly devised to remove any possibility of slippage, hence the name BedRock. By installing three setscrews, counterpoised two against one, the frog sits immovably in the sole permanently. The Bailey pattern frog is also anchored to the sole with two setscrews through the frog directly to the sole. This too works perfectly well, is simpler and, in general, never moves. Some makers have attempted to cast the sole with a built-in or cast-in incline as a single-piece casting. I never queried why it didn't work well and seems always to have been abandoned, but perhaps the combination of metal mass in one concentrated centre reacted negatively with any thinner areas around it and resulted in periodic distortion through different exchanges of temperature. No matter. It still seems remarkable that the plane adjustment mechanisms, the sizing of components, and other detailing, have all remained exactly the same for around a hundred years. Looking at the BedRock, we again see that the minimal difference to the overall Bailey-pattern remains testament to the quality of Leonard-Bailey's investment of energy to invent a totally adjustable plane by the tweaking of a lever and the turning of a rotary wheel singlehandedly with the dominant hand. Norris and several British makers came up with a threaded-rod adjuster that could also lever left and right to align the cutting iron to the sole and then turn for depth adjustment too. This was copied by the Lee Valley Veritas range of planes. Compared to the Bailey model, it was slow, needed two hands, and was less precise than Bailey's system in the bench plane range of bevel-down planes and in my view never an equal to Leonard Bailey's endeavour for quick efficiency.

The Main Differences Between the Two Frogs.

If you are a seasoned hand tool user or enthusiast, you will already know that the key differences between these two frogs are in the shape and types of frog. We tend to think that this alone is the difference, but there is more to it than that. It's as much to do with how the frog sits, adds to or reduces weight to the plane, the clunkiness weight often gives and how it feels in the hand, in the work and in the working of it. I have worked substantially with all plane types through almost six decades including every BedRock the makers of which always introduce it as a superior product for a range of exclusive reasons. My quest now is to give my point of view so that people can rethink if they indeed think that planes thus made will make them the better woodworker or that accepting the plainest of Stanley's the lesser man- and woman-maker. I can make any Stanley create as well as the highest of high-end maker planes and give me even more; it's my belief that you can too. I pass on any working knowledge I have from using them for half a century most days. It's not an advocacy for nostalgia in any way. The pure reality of using them make things crystal clear and you too will be able to create wonderful work with any £15-30 plane for the rest of your working life.

On To the Frog in Your Throat

These points of contact can vary in precision and quality but generally, I have found them to be good and in need of no refining. That said, they can be readily refined if needed. If, however, there is any variance in these levels, tightening them down is not the answer as this can flex the sole into a twist which therefore will twist the outcome of your plane work. It is not likely that this will happen. I only saw it once in hundreds of planes. A quick file with a mill file, abrasive or diamond hone readily takes one or the other down, and any rocking will be easily detected.

What modern-day exponents for the BedRocks inevitably do, disingenuously in my view, and to sell something in most cases, is tell you first of all that it is regularly necessary to alter the throat opening to deal with plane chatter and difficult grain and how easy it is to adjust that throat opening of the BedRocks over the Bailey-pattern version. This is something most woodworkers rarely if ever challenge because, well, they simply don't know. What you do need to know is that in 99.9% of all woodworking tasks with plane work need the throat opening to be wide open, somewhere between 2-3mm. At this more open setting, nothing will generally go wrong. At this opening, shavings are regularly emitted from the plane stroke on stroke, day in and day out and throughout the life of the plane. I have used the same Bailey-pattern plane for 58 years to date. It's been at the same setting for almost 58 years to date. I have only closed it tighter half a dozen times if that and I could have managed perfectly well without it. It's been the same throughout the ages for 150 years of Stanley planes and it's no different for any maker that copied the Stanely planes when Stanley stopped making, whether that be the Bailey-pattern or the BedRock pattern. The most critically important thing to understand though is not the ease of changing the BedRock over the Bailey but that which they never tell you -- when you do change the throat opening of any BedRock plane, no matter the maker, you always automatically and unintentionally reset the plane's cutting depth to a deeper-cut setting when you close down the throat even by any amount whatsoever. On some, if not all work, this will be devastating if you forget to also readjust the depth of cut to compensate for the downward slide of the BedRock frog. Why is it that no one making or selling BedRock planes ever mentions this up front? Why do you think?

In my tests on the BedRock high-end planes, the shavings went from a near and, for me, immeasurable thinness to an impossible stroke because of the vastly increased depth of cut resulting in excessively thick shavings. This is without changing the setting of the depth via the usual way using the adjustment wheel. We should perhaps talk about this first. I initially recognised this at a US travelling woodworking show where a demonstrator showcased the ease with which he changed the setting of the throat opening to an audience of a half a dozen men. This feature seemed to fascinate the cluster of people surrounding the planing demonstrator yet he never told the audience that you rarely and in many cases never actually use the feature at all. They smiled and marvelled at the efficiency and the engineering, the weight of the plane and its fine feel and combined with an explanation of how this had improved over "ordinary planes such as the Bailey-planes" I became more interested. Just what was this about it being easy to change the throat opening?

All through my career of woodworking, the men I worked under and with never relieved the setscrews holding the frog to the sole in Bailey-pattern planes. They simply turned the adjustment setscrew beneath the depth adjustment wheel, placed their planes to the wood and continued working with them. That didn't happen with the demonstrator there in the US show. Why? Asking myself this question I remembered that BedRock planes were the rarity and scarcity and no one I ever knew in Britain owned anything but the Baileys. I picked up the demonstrator's plane and felt for the cutting edge. There was my answer. The blade protrusion was suddenly way, way too deep to function. I moved along knowing then that the plane was indeed automatically reset to a new and significant depth simply by closing down the throat a little; I felt this to be a fairly useless improvement and understood why the plane was so rejected by working craftsmen. The feature espoused as advantageous actually resulted in a disadvantage. This for me was a major issue of counterproductiveness. Any advantage was suddenly negated even though the advantage was indeed questionable. The quick change of the unneeded throat change resulted in a slow set of the plane's depth of cut and thereby the immediacy of functionality.

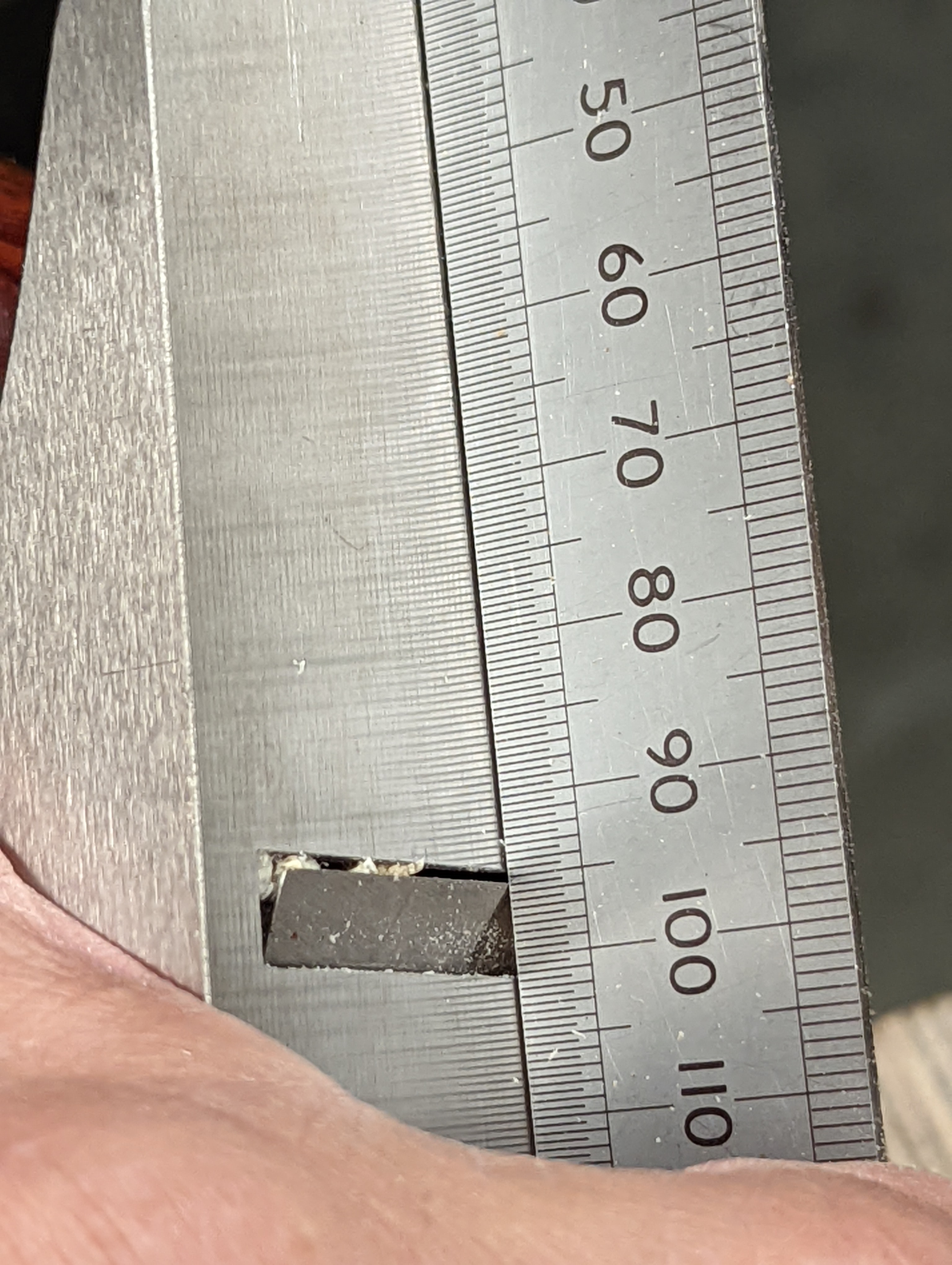

Turning the centre setscrew that shunts the frog up or down its inclined platform on the insides of the soles of any and all BedRock planes one full revolution from the zero point, the point of taking the most minutely thin shaving off the wood, closes down the mouth opening from about 2mm to somewhere close to give or take 1mm. It's a small but necessary gap, not much of an opening at all, but one you might go to to tackle something really wild and difficult on a special hardwood you needed for something you are making. But here is the real issue. The depth of cut achieved by any turn large or small to close down the throat some also markedly alters the depth of cut and takes the blade down through the throat of the sole by about as deep as you can set the plane depth to using the wheel depth adjuster. In other words, the cutter will not take a shaving so much as gouge deeply into the wood and most likely scar it irreparably as shown above. The chief and significant point in this is that this change always happens and cannot not happen. On standard Leonard Bailey pattern planes, on the other hand, this never happens with changing the position of the frog on the much-dissed Bailey-pattern plane because it cannot happen. Why? The frog is set paraplanar to the face of the sole on two levels but without any incline so moving the frog backwards and forward is a parallel motion along fixed-height points.

On BedRock Planes

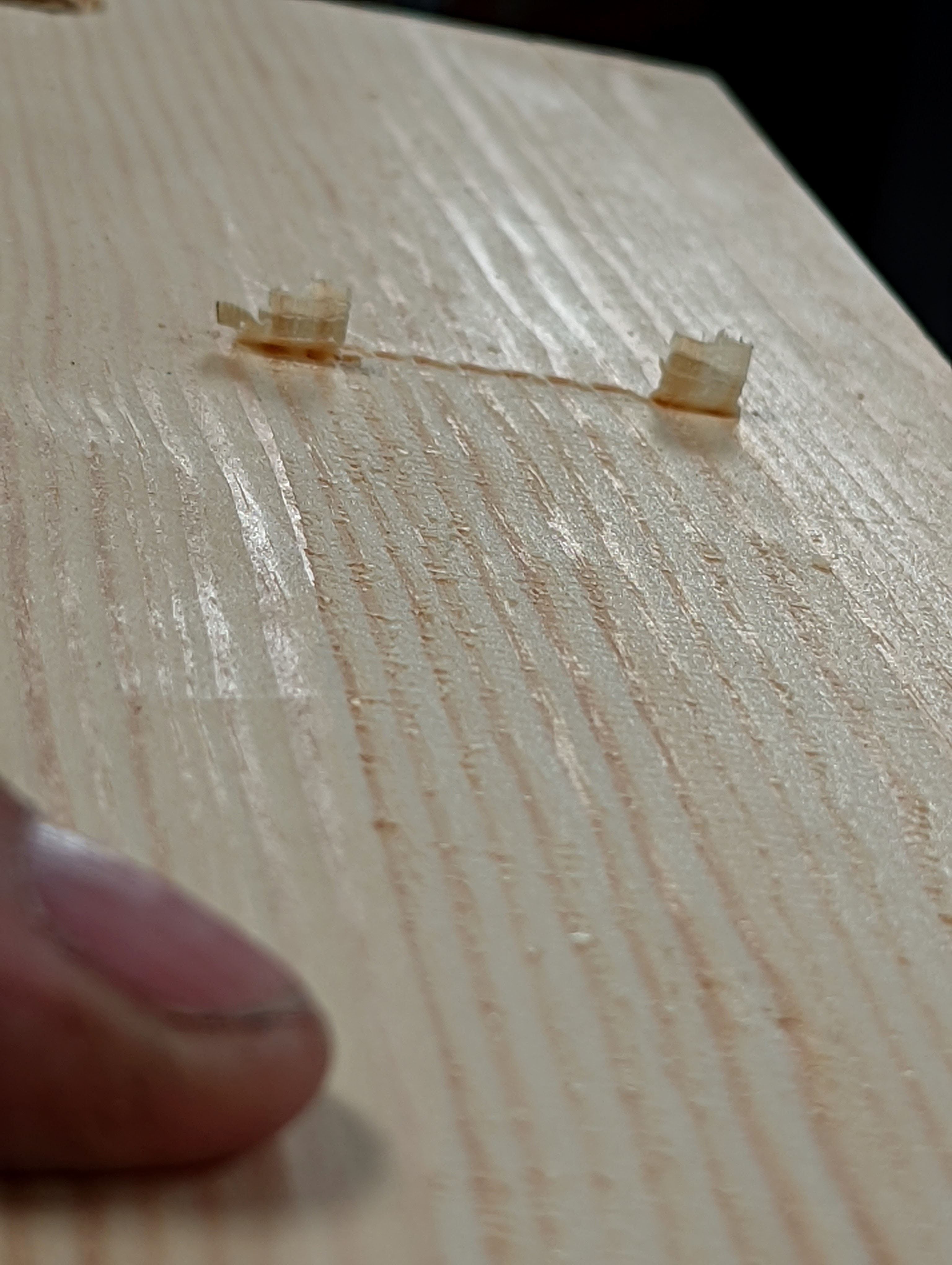

Taking the plane with its frog shunted forward to close down the throat from zero-thickness shaving both narrows down the throat opening but at the same time, in tandem and unintentionally, automatically changes the depth of cut to a massive .62mm -- so thick the shaving is not a shaving but a staggered fractured coil that then leaves a skudded surface like you have never seen before. This means the supposed benefit the BedRock plane pattern might possibly offer is sorely negated by having to majorly adjust the depth of cut to a safe level. Even in experienced hands, this is no minor inconvenience to anyone planing wood.

Conclusion:

This has been an interesting consideration. I think covering off the major concern has identified several different issues. The major danger here might be throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Why would you? Identifying the fact that you do automatically misset the depth of cut of your plane iron will also ensure that if you adjust the depth of cut back to zero via the depth-adjustment wheel you eliminate or at least minimise the risk of damaging your work. If indeed you become practised in automatically considering the depth of set after closing the throat down before you apply the plane to the wood you should have no problems. You already own a good plane. If you listen to what I say about the unlikelihood of needing to change the throat opening then your plane will always be ready for action. Just use it. If on the other hand, you are perpetually working with wiry- and awkward-grained woods then you will get used to resetting the depth of cut. It's just important to know that BedRock planes come with a built-in problem and that they did not nor do they resolve any real-life issues.

The Bailey pattern frog, even when cinched tight, can still be moved forwards or backwards with the whole assembly in place, clamped down and solid on every `bailey pattern plane I have used. But cinching the two setscrews tight and then backing the screws just the smallest fraction of a turn will not render the holding capacity of the frog to the sole by any noticeable and negative amount. The frog will always hold its place just fine. The main advantage in this is that you can readily move the frog back and forth with a simple turn of the setscrew at the back of and lower part of the frog. Doing this in no way changes the depth of cut. Simply put, alter the throat opening by any amount you like, apply the plane to the wood and the depth setting remains just as it was before the change of throat opening size. You just might never need to ever change the tightness of the two setscrews for the rest of your working life. Just like me!

Comments ()