Obsessing Flatness Can be Unreal

Over the past decade, I have seen woodworkers obsess more and more about flatness in planes, plane irons, chisels, spokeshave cutting irons and others. The obsessioning began in the 1990s, got worse in the 2000s, and left a residue of legalism that makes woodworking more unreal than real. I understand that some men in woodworking are as keen on getting a perfect edge and a single shaving as a result of compulsivity. They are not interested in using the plane as I might when fitting and trimming, surfacing for a level plain, or removing twist, cup and bow in readiness for starting the joinery in a project. I truly understand this and then too the hope of getting a continuous shaving in maple ten feet long, full width at two inches, and the thickness of the proverbial onion skin consistency of a thou' thick. Countering the tendencies of gurus saying this is essentially what masters strive for and creating an unrealistic trend and so endeavor to normalise what I see is pure misguidance and very impractical. Before you know it, if someone doesn't say something, you will be spending more time flattening your chisel backs and plane irons than actually working the wood when at the bench, in the zone such obsessioning is in general quite unnecessary. The exaggerations of this kind soon become online trending and indeed, worse still, a belief can enter that becomes essentiality when such is far from necessary at all.

Chisels, plane irons, spokeshave irons are the primary edge tools in working with wood for furniture making. I'll leave out draw knives and axes here -- we don't really use them much beyond some minor elements of green woodworking such as chair making and such nor in joinered, at-the-bench woodworking. Whereas it can be said that it takes only a one-shot deal to flatten a chisel as an initialising process when the chisel arrives, it is also true that arriving at that flatness level is generally only really necessary for paring chisels such as we use on the more refined bevel-edged chisels used in refining and making different joints such as dadoes, housings, wide tenons and sliding dovetails across wider boards. That being the case, and I believe in general that it is, it's probably a good idea to keep one or two bevel-edged chisels for this dead-flat application and not worry too much about your everyday chisels. I generally use the basic bevel-edged chisels I have relied on throughout my life as a full-time woodworker and furniture maker. In the last decade, I use mainly the ones I bought from Aldi in 2010 for £2.50 each. I am sorry they stopped selling them because they are still the chisels I reach for over every so-called premium maker version that I own and for good reason. Someone recently asked me if I would be more realistic using these better quality chisels alongside my utilitarian versions from Aldi and MHG. The truth is, I use the term utilitarian very loosely; these chisels have proven to be very comfortable, well balanced and refined enough for every ounce of my finest woodworking.

So where are we on flatness? Flat faces on the backs of edge tools and blades create the essential cutting edges we need for clear execution of our work planing, pare cutting, chiseling and chopping, etc. The flat-face initialising is generally a one-off process. We take the chisel and plane iron and spend a little time truing what may well not be flat from the manufacturer or have become slightly rounded by our inexperience or the work of previous owners before we took possession. This flattening of the wide face, once done, needs either zero or very minimal revisiting through the lifetime of the tool once done. Think about it with me. If you spent a few minutes flattening that wide, flat face, all subsequent sharpening is worked on the bevel alone. It makes sense, it's much easier to abrade a narrow face of no more than 10mm than the whole of a flat face 50mm wide by 50mm long. So here we see that when sharpening in the day to day we are taking the bulk of steel down from the bevel alone. It's just practical to reduce the smaller face only and it's of course not necessary to do much at all beyond breaking the burr that forms on the wide face side.

When we use the chisel and the cutting irons in planes and spokeshave the elevation of the blades means that the very fine cutting edge cuts into the wood with uneven or unequal pressure. The blade enters the wood at the start point and is pushed forward into the wood. At the rake, the fore-edge of the blade has top pressure only whereas the underside of the cutting edge is completely unsupported. This means that the steel fractures in the opposite direction to the force being applied and the ultra-fine cutting-edge edge fractures. All the more does this happen when we hit tough areas surrounding knotty areas which is always denser than the rest of the surrounding wood. Hitting knots, especially the superhard spruce and pine knots we encounter in softwoods, fractures the edge all the more. Some woods, hardwoods especially, have silica in the fibrous strands of the wood and so dull the edges much more quickly. I know of two woods from experience that do this; mesquite and teak, but there are others. Where does the greatest fracture resulting in a rounded over edge take place? Towards the bevel side of the edge. This then makes sense that we repair the damaged edge on the bevel alone. Of course, I am generally talking about the plane and spokeshaving, one and the same if we are using #151 type spokeshave where the blade is inclined. In wooden spokeshaves it's different. The blade is virtually the sole of the 'plane'; with a slight one or two-degree elevation on the underside to allow relief for the cutting dynamic; the pressure, though still on the top bevel, has a much lesser impact. This is why these spokeshave types stay sharper longer. In chopping with chisels the pressure is equaled to both sides of the cutting edge and so too with paring because the paring stroke results in applied pressure to both sides fairly evenly hence in use the pressures tend to result in better edge retention and less fracturing for a long period. I have cut as many as fifty good sizes mortise holes in oak with a half-inch bevel-edged Aldi and Lidl chisel before any need for very minor resharpening.

Chisels in use are rarely held at a rigid angle as in the case with planes and spokeshaves, which have the blade held firmly and inflexibly to the bed angle casting. We don't think much about it if at all, but when we chop with a mortising action, say against the ends of the mortise hole, we rarely actually keep the flat face verticle but actually alter the angle as the chisel deepens down to an imagined verticality rather than one we can see or indeed a fixed one. If you take a minute or two to gauge the angle when using a freshly sharpened chisel and then test again an hour or two later, you might be surprised that it will not be as verticle but you will automatically be compensating for the dulled edge. What you are effectively doing is evening out the pressure from both sides of the actual cutting edge. Until you abrade down the bevel of the cutting edge again, and you will continue to do this. `When you sharpen the bevel again and apply it to the wood for chopping, you will be nearer to verticality again.

Another support for what I say is to lay the chisel onto a surface of flat scrap wood, bevel up, and nudge the chisel along with just a finger on the end of the handle. If the chisel immediately catches along the cutting edge then it's sharp. A newly sharpened chisel should always catch. Of course, I am not talking about all woods. Dense-grained hardwoods, oily woods may resist more, but oak, ash, cherry, walnut, all the softwoods, etc. Now if the chisel is well used and dull it will glide along the surface without catching. Now by lifting the handle of the chisel with the cutting edge on the wood surface try applying a little pressure at different angles of elevation. The more you have to lift, the duller the chisel cutting edge will be. You will notice this when paring down end grain to the nubs of dovetail pins or plugs covering screws.. Paring the cheeks of tenons will also indicate the level of sharpness as you will find yourself elevating the handle to engage the wood with the cutting edge. It always surprised me how many woodworkers using a fabric wheel on a buffing machine end up with a dulled chisel or plane iron because they fail to engage the chisel at the optimal angle and then allow the buffing wheel to polish the cutting edge on the end itself. They also polish the back face but fail to keep a distance from the cutting edge with the main body of the mop. This then rounds the end and the chisel will not cut well if at all.

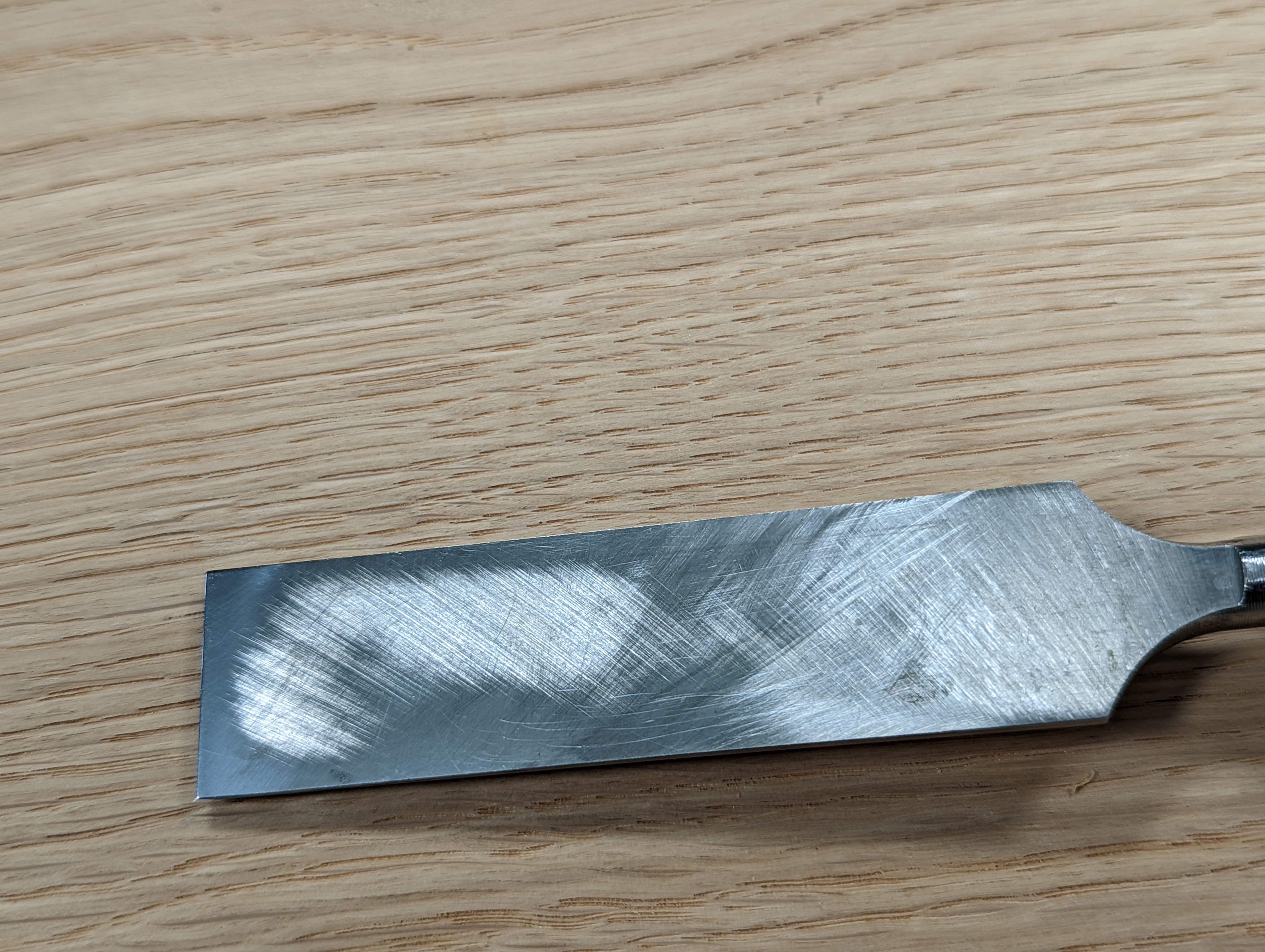

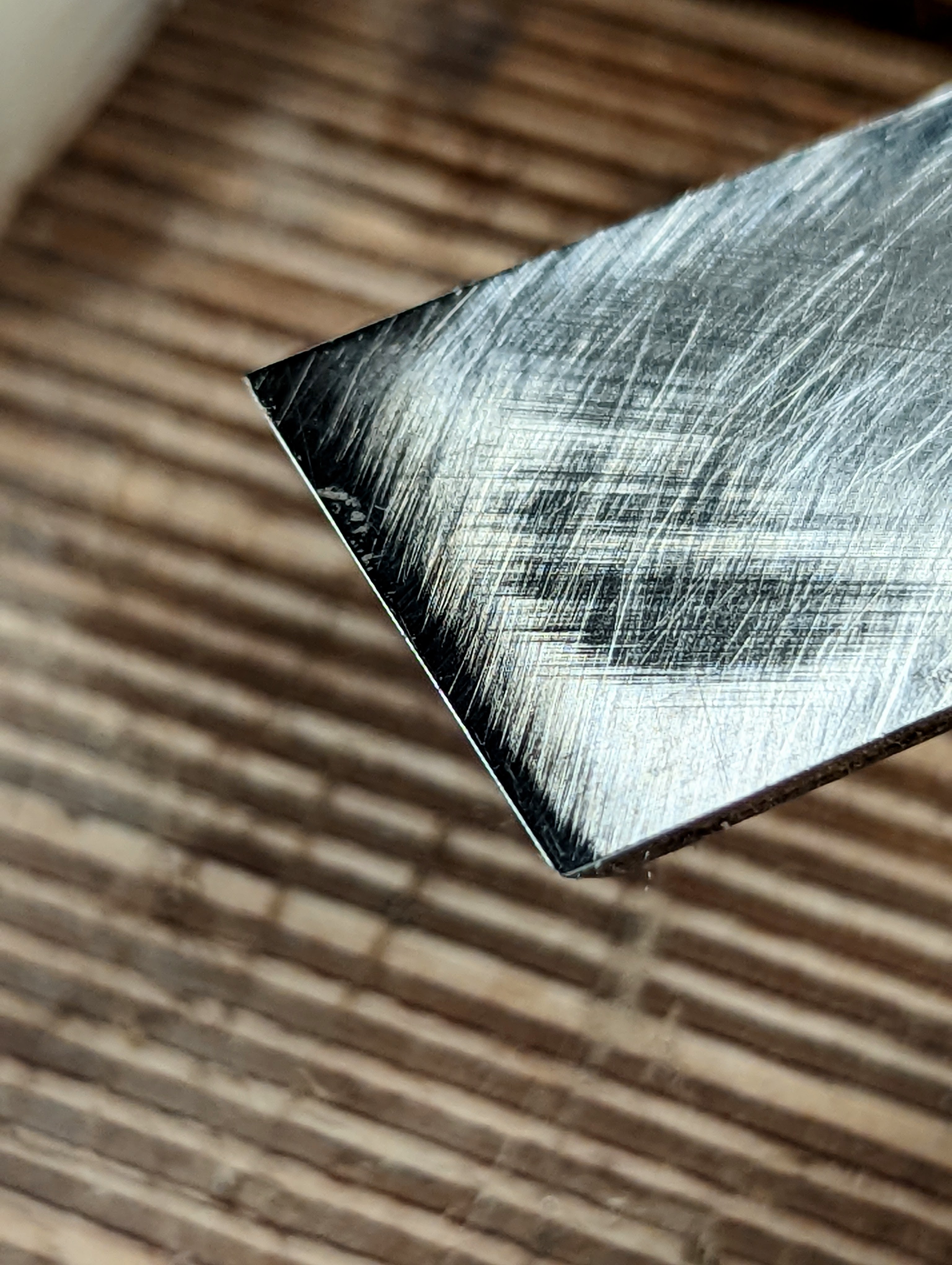

A chisel and plane cutting iron back need not be dead flat: it's just something to aim for and there is no reason not to achieve flatness as near as possible. This is my chisel. It's clearly not dead flat but it is actually ideal. When I sharpen this chisel I focus only on the bevel and take away the steel of the bevel alone until I have a burr and then an immeasurable touch more. I flip the chisel and with a single pull away from the cutting edge I break the burr. Stropping the bevel on the strop 30 (or so) times polishes the bevel. I use a 10,000 grit polish and this gives a mirror finish to my bevel which effectively means that the abrasive is so fine it has abraded out any major striations from previous grits to a higher level of polish and thereby sharpness. Remember that the flat face was initialised a long time ago -- in my case, over ten years ago. This flat face was flattened on diamond plates I know to be flat and then polished out with the 10,000-grit abrasive compound on wood and not leather. I don't recall returning to this process in the ten years of use.

With regards to the flatness of plane irons. I have written on this issue before and covered it in my book Essential Woodworking Hand Tools by cutting away the side of a #4 Stanley plane to show exactly what happens under the pressure of the lever cap in relation to the cap (chip breaker USA) iron and the whole cutting iron assembly within the body of the plane and the frog. Even if a plane iron is far from flat, that's hollow, twisted or whatever, the leverage pressure applied to the cutting edge end of the assembly is absolutely forced hard down to the bed of the frog and indeed flattened to it by the simple leverage of the lever on the lever cap. That said, it is easier and practical to sharpen if indeed we have a relatively flat iron to begin with and that is why in general we do ensure the near flatness of the larger flat face. The best way to test out a plane iron's functionality is to sharpen it, install it and see if it works. It most likely will. You will not have to have a flat face within thousandths for the plane iron to function perfectly well.

Plane sole flatness has value but not perhaps as much as you might feel. I use the word feel strategically. Whereas a plane's flatness plays into our endeavor to create flatness in our wood surfaces, it's not really the be-all and end-all of it. We can overplay our quest for flatness believing that once we flatten a board, billet and beam, the job's done. Rarely is that the case Wood is a constantly moving entity in the lives of woodworkers. How often do we plane a board true and flat, machine wise or hand wise, and the following morning we come in and it has cupped, shrunk or in some other way distorted. It happens all the time. I once put boards in the clamps two feet wide in Texas and stood it on end and the following day, 24 hours later, all the clamps were on the floor in a heap. John has been gearing up for a hands-on class here and shook a #4 plane at me. and the beech handle rattled as he told me he had just set up the plane and tightened the handle just yesterday. Over night it had shrunk enough to be loose. We do a variety of things to minimise changes in our wood and indeed we aim for flatness. After my 57 years in the saddle, I have come to accept that wood will always, always move. We aim for flatness mostly to complete our joinery be that edge-jointing for gluing narrower boards for wider panels or for the mortise and tenons we rely on to constrain our wood and make our boxes and frames, carcasses, etc. It's the best we can hope for. I have yet to come across a Plane that does not distort with exchanges of heat, especially so in high exchanges of differences. Living in Texas I saw this the most. This week we saw a Texas record of 112F (44C). I will guarantee the plane's soles moved some. In my life there I went from several degrees below to 90F the same day. The other thing that is seldom if ever mentioned is the exertion of force we put on the planes themselves and especially when we move up to the longer range of planes. The longest plane I ever use these days is the jack plane. There is no point in any of the other longer ones. They do not stay flat, they are ungainly and awkward to use, and most people including myself cannot maintain the kind of registration needed to the wood to create a decent level thrust. In 57 years, I have never failed to achieve everything I need with a #4, a #4 1/2, a # 5 and a #5 1/2. The only reason I really keep the wider versions, the #4 1/2 and the #5 1/2 is when I am planning the edges of two boards side by side for making panels.

I understand the onion skin thing. It's one of those challenges we charge ourselves with just to see if we can. A bit like climbing a mountain just because it's there but the quest replacing the enjoyment of the scenery, the exercise and much more by the intensity of the obsessive often. I have been on climbs with others where the journey was pretty much ruined by the one who constantly pushed in a rush to get to the top to be the first or beat the record time or their personal best. My interest in sharpness is because it perfects my work in myriad ways, not the least is the crispness of the look, the minimising of using abrasives and then, more importantly, the accuracy and the skilled craftsmanship I achieve.

Comments ()