It's All Gone

I looked inside the wooden box where his tools were always placed in an interlocking pattern that allowed each tool to fit into or beside another but only one way. I knew to look only for a short second, barely a glance, any longer and I'd get a cuff around the head and a harsh word accusing me of 'casing the joint ready to steal something' when his back was turned. Of course, I wouldn't, but such was the culture of the day. Ten benches with a four-foot spacing between and set in a rectangle would be the rarity today as it was then. Wood and the working of it from beam to chairs and tables by hand with an odd trip to a machine in between are all but gone in most shops these days. Here, I am talking about toolboxes and chests laden with ebony and rosewood infil planes, wooden squares, sliding bevels and much more. Wooden plough planes, filletsters were fading out as tools of use, Jack planes in beech and then some vintage tools we would most likely have no knowledge of any more lined the insides of the boxes and perched on the benches nearby. I was in those transitional years when these chests and toolboxes would go with the man when he left for final retirement and they would never be replaced; no one would bring such things to their workplace to work from them or use them again in any ensuing generations. I saw it then and it did indeed come to pass.

I watched as the first powered router guided by special fence guides routed out recesses for hinges, and electric drills were replaced by battery-driven versions, in the same way I saw the first pocket calculator add subtract and multiply in a salesman's hand for the first time. It cost almost a week's wage. We look to the past with reverence as a sort of mysterious period when men made to levels of excellence we see in the mansions of the rich and powerful past. Such work is no longer made and those tools exist mostly in the realms of collectors, museums and associations. Tools and trades history societies do little if anything to keep craft alive except in the most artificial of ways by somehow perpetuating historical obsolescence; instead of encouraging the true art and craft of craftworking, most colleges give a nod to the past by using teachers who have little if any mastery of handwork and craft by teaching a one-day class on how it 'used' to be done 'in the past'.

In my world of making nothing really changed much. I'd made up my mind and made hand tools work through the half-century of making and selling everything I ever made. A made-up mind is the key to everything. Whereas I was raised with machines, it was also in parallel to the daily hour-by-hour use of hand tools too. In my workplace, what one man didn't know another man did. There was a healthy exchange of ideas, thoughts and skills that passed between woodworkers within the region as they came to trust one another by working together. I am not too sure that that really exists today simply because most never develop that sense of coequality and trust and then too, with the demise of truly skilled handwork and the need of it, there is no need for skilled work anyway. The natural progression is therefore that skills die a little bit year on year. In my early years, when one left a company and transferred to another the cross-pollination was remarkable, I thought. Conditions, work type, coworkers and geographic locations all influenced and facilitated this exchange of not just labour but thoughts, ideas, helps and supports alongside the reality that it was healthy for the craft simply because with it came the exchange of knowledge to perpetuate diverse skills within the trade. Unfortunately, in my view alone, it seems, it wasn't enough. Skills were tragically lost and mostly because of lack of self-belief. Until they see it done, carpenters don't believe that I can chop a recess for a hinge accurately and at speed in a minute or two with just a chisel, a gauge and a mallet. The difference for me is that I can dip the back edge of the hinge in a perfect plain and 'Scotch' the hinge in the traditional way that no powered router can.

As the skills diminished and global mass making created its own self-diminishment of skilled workmanship, my craft was to go. It went to the point that it is really all but gone as a way of industry. It really hadn't needed to, just that industry believed it needed to and I get that. Business people buy and sell companies as an investment and want a high-profit yield to fill their bank accounts. They are just investors for the making of money and little else. `They can't really buy people with a moral ethic for art, hence the demoralisation of style and skill where every interior looks identical, just about. I am amazed at the low cost of wooden furniture produced for use in commerce and domestic places. I pay £300 for enough oak for a dining table yet industry makes, supplies and distributes an oak table from China for just a couple of hundred pounds more and it's really quite well made too. Indeed, it may not be heirloom quality but it will last a growing family until the kids leave home. How to compete with that?

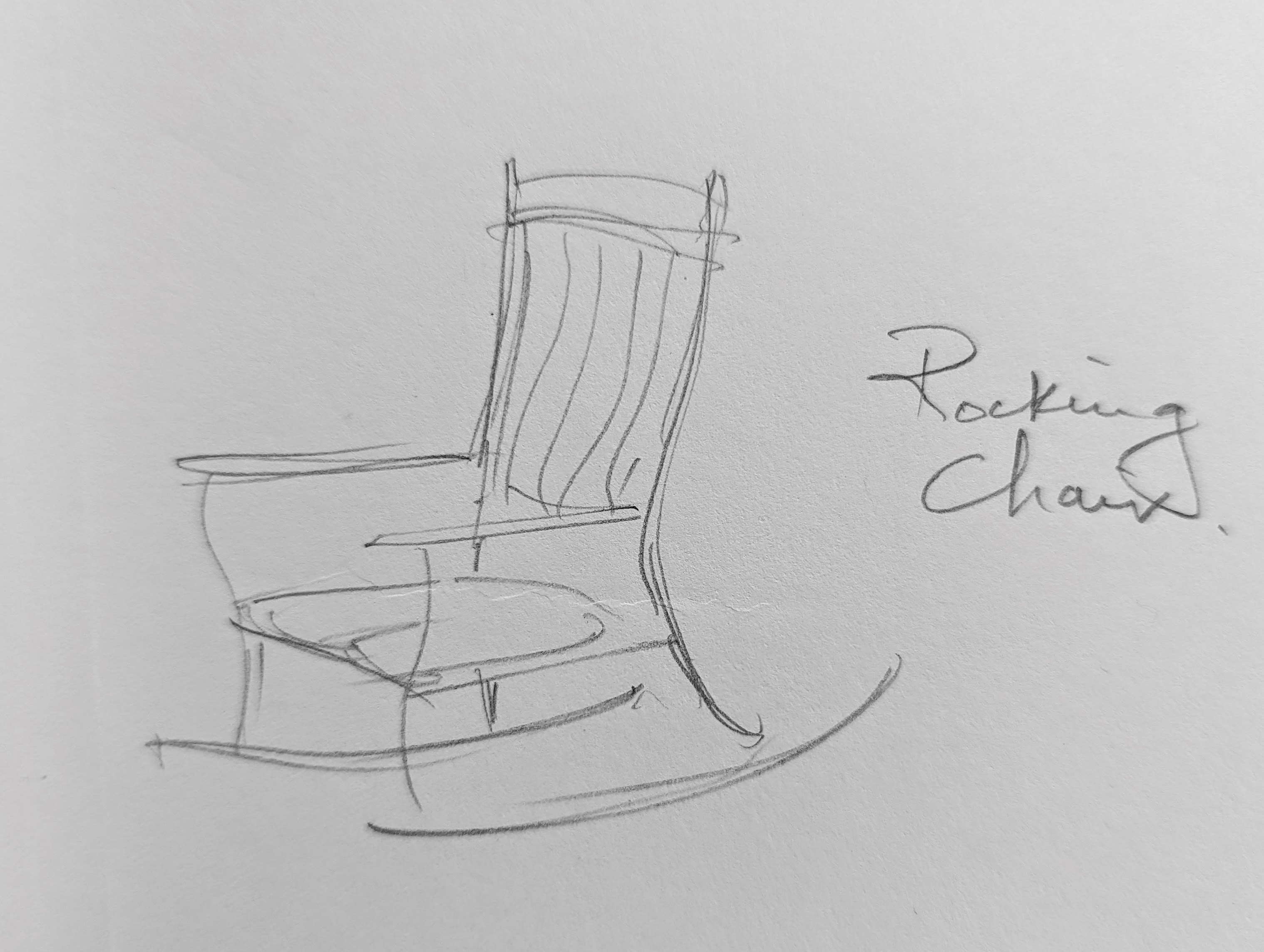

Well, the truth is, I did and I still could even at or especially at my age. You see there is still a customer base that looks for other ingredients when they are looking for a piece to buy. Can they find something to make do or can they buy something customised to fit and of a quality and style matching their expectations. Someone asked me how I can justify the price of $6,500 for a single rocking chair when they mostly sell for a few hundred at most. I think that most woodworkers sell what they make based on some kind of hourly rate. I recall one of my own customers balking at a price for a piece and trying to beat me down on price. I stopped him at the hourly rate thing. "If three independent carpenters come to your house and they are given an identical set of plans to build you whatever deck is on the drawing or even the specs for a whole house, you might expect the prices of all three to be closely comparable," I said. When you come to me and ask me to design a piece of furniture like a rocking chair, something like that, you are not just paying an hourly rate, you are paying for my design, my design ability plus my ability and skill to make it. History has changed from the days when a man in the 1700s, 1800s tipped his cap or tugged on his forelock and said, Thank 'e' kindly ma'am!"

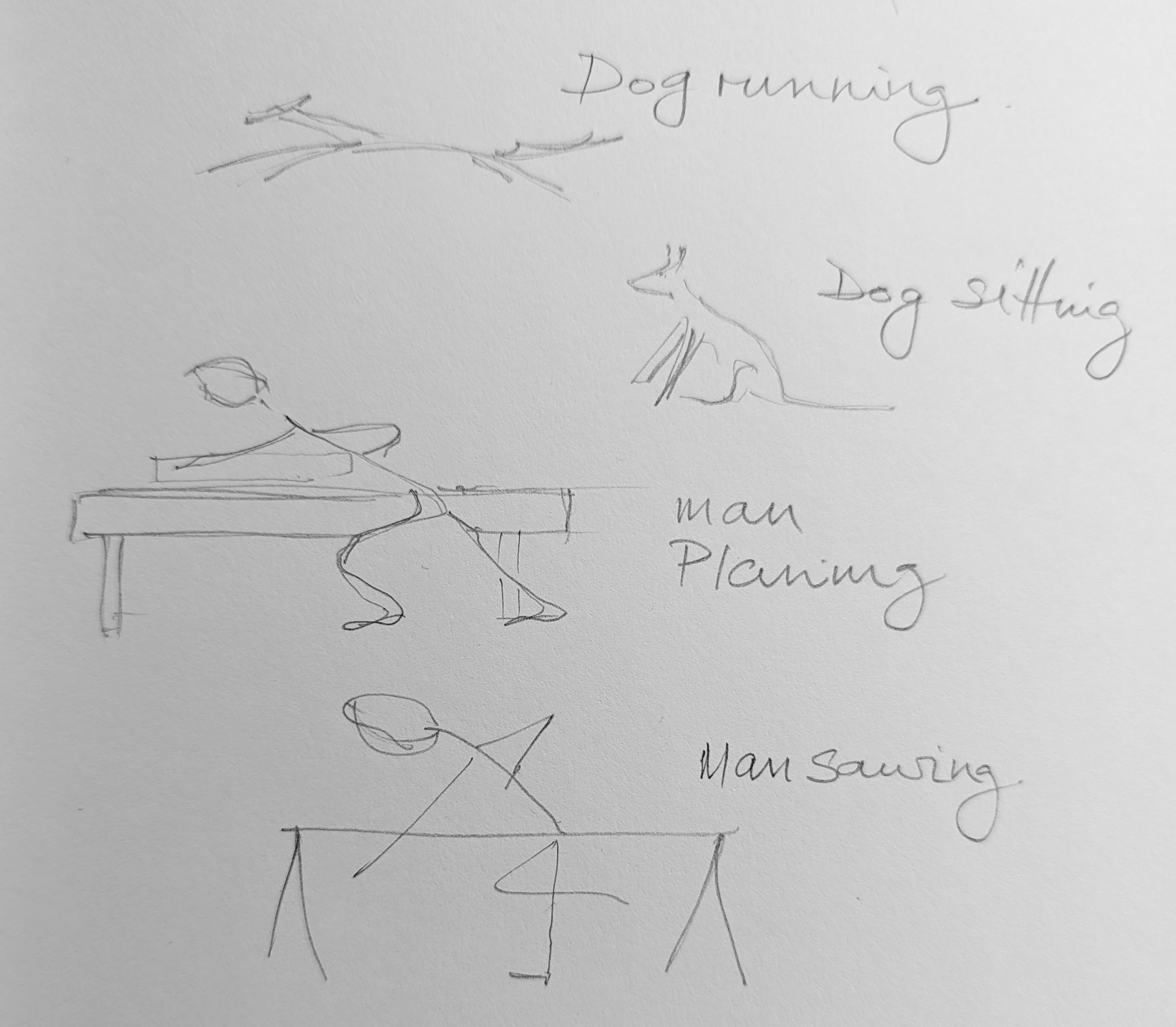

My ability to sketch out a drawing in front of customers and then make the piece according to the drawing is the scarcity and such skills should be mastered for the immediacy they give a craftsman for the customer. I chose this path with drawing when I was in my mid-teens. It paid off. It wasn't so much that I was good at sketching but that I saw how people could not visualise things and so how could communication of an idea become the bridge we both needed without a drawing, and even the most basic sketch can communicate that you and they are on the same page. Of course, we automatically believe that we must be good at sketching and drawing before we do such a thing but the brain fills in the gaps, in the same way, cutting off the top half of a line in a sentence does not mean we cannot still quite adequately read the line. I found that with the most basic sketch, customers felt more confident that they would indeed get what they expected. Combine that with a portfolio of finished pieces and people felt it was less of a risk giving the go-ahead. These were the days when no one owned a cell phone or much of a camera and of course, social media wasn't a possibility at that time.

I think that it is true that many if not most people don't believe that they are able to be or capable of being creative and perhaps this can be attributed to the reality that many teachers never leave education to become especially skilled enough in particular areas of creativity to go beyond a textbook and manual and therefore equally incapable of talent-spotting creative people when they see them. In my sphere of making as a maker, photography, technical drawing and then sketch drawing too, I automatically project myself into the doing of most things. But, that said, I know my limitations when it comes to car mechanics, some plumbing work and electrics. otherwise, my creativity has translated into my using digital energies to be creative there to some level too. I have worked through elements of PageMaker, photoshop, social media in tandem to art too. necessity is indeed the mother of invention so inventing has become important to my life. All in all, I find that mastering one area of creativity often equips us mentally and physically, emotionally. Rarely if ever will this be reversed in the sense of people taking software engineering into the manual working realms though, of course, I have seen significant changes there in recent decades as all the more people seek other ways to express themselves creatively. This shift in recent years is coupled with people seeing the internet as a way of extending their ability to both make and even earn. Additionally, dumbing down making to a machine operation where shooting staples and nails, pocket-hole screws and so on give you the wham-bam effect for mesmerising an audience looking more to be entertained than skilled.

Becoming any kind of a creative takes the acknowledgment that gaining any kind of mastery takes dedication and practice. It's an ongoing commitment not to cut corners but to learn how to become as highly efficient as possible and then economical with various elements ranging from time to money to materials and more. This was drummed into me as an apprentice when I thought time didn't matter so much or that a miscut resulting in the need of a replacement piece could just be taken from the wood stacks. Nuh uh! No, no, no! So much to learn!

Comments ()