Hinges and Hingeing

Hinges come to us in a wide range of highly sophisticated types ranging from the kitchen cabinet, 35 mm hinges intended for mass-making cabinets and giving multidirectional adjustability for face-fixed, overlaid doors via mechanics built into the hinge via several cantilevering setscrews to simple, traditional and basic butt hinges with zero adjustability once fitted.

The first provides (above`) permanent realignment possibilities catering to twist, drop, sag and parallelity and just about any other shifts that take place in the lifetime of heavy-use cabinets. In general, these hinges have become ever-more sophisticated by adding soft- and self-close mechanics that barely make any noise when opened and closed and when fitted and maintained properly. Would I use these adjustable hinges on fine furniture? No, at least I doubt it. I have made cabinets that used them in the past, primarily because it was what my customer wanted at the time. For several reasons, mostly adverse extensions within the hinge that increase leverage, these hinges don't last too long. perhaps three decades but generally less. I also have some pieces of office furniture that are fitted with these hinges and though they are perfect for their application, I wouldn't like them in the furniture I make. But of course, hinges span the gamut from small boxes to massive entrance doors.

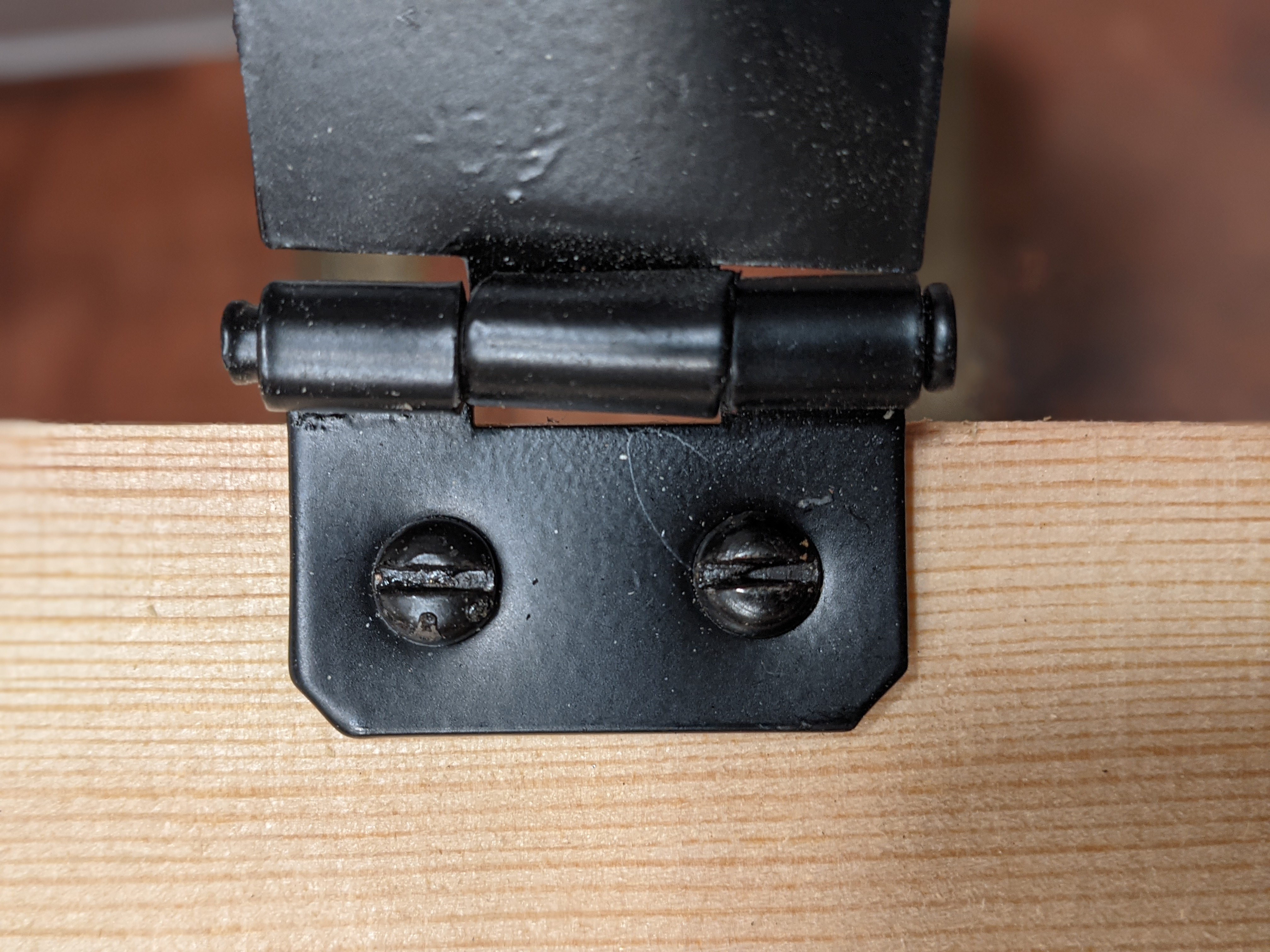

Hiding hinges is not part of my objective in making. A well-fitted two-flap traditional hinge, recessed into stile and frame or case is a lifetime probability intended to and likely to last for at least a hundred years. Some such hinges have hardened steel anti-wear washers fitted between the moving contact areas for improved longevity but this is usually on heavy doors, but even the softer metal brass hinges will still last for a hundred years of ongoing daily use. Face-fixed hinges are usually the most evident of hinges in that usually they fully face the outside elements on the door's most evident face. Some face-fixed hinges are indeed purely utilitarian whereas others combine ornamentation and strength and include an overall structural support even to a whole door. These too have their place. Garden gates exemplify the functionality of face-fixed hinges and other fastenings. These are the easiest of all to fit. Wedge the door in place, place the hinges carefully and drill holes accurately and the hinges will function just fine. Again, decoration is not usually what I want on my furniture but `I do like my hinges to be evidently present.

Recessed hinges

Recessed hinges are very often avoided by woodworkers, especially in commerce, mostly because they can seem a fussy way of hingeing a door or a lid. In general, you must work within quite tight tolerances to get everything to align well, usually within hundredths of an inch or centimeter anyway. Many assumptions surround the recessing of hinges and it's this that I want to talk about because it is these assumptions that often lead to our being misguided in our fitting.

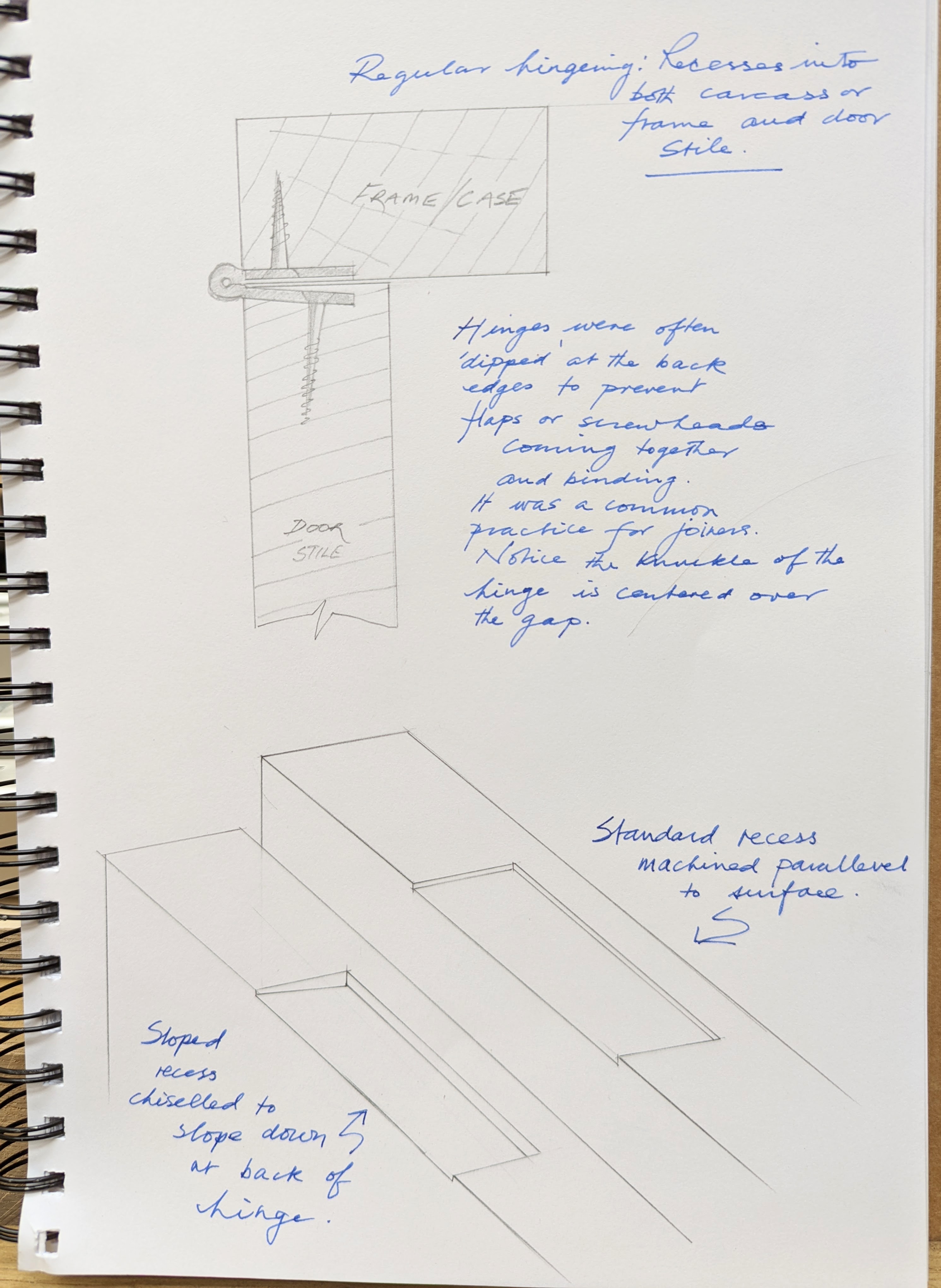

The recesses are usually chiseled or power-routed into the edges of doors to receive the flat hinge plates with one being attached to the moving element and the other to the fixed immovable one. Of course, as always, there are strays from this. A box with a face-fixed lid for instance, can have the hinge recessed into the underside or inside the face of the lid but then recessed into the rim of the box. That's quite common and it's easiest to do too. Whatever way you develop your hingeing, an important element is the amount of gap there is between the hinge flaps when closed. Unfortunately, there is no such thing as an industry standard. This then needs for us to decide what gap we want, whether we want the hinges deepened to a depth deeper than the thickness of the flap of the chosen hinges and things like that. Our greatest concern is the gap distance. Too much looks ugly even though functionally it will work well, too small and the wood can swell closed the gap due to humidity and the door or lid will stick and jam.

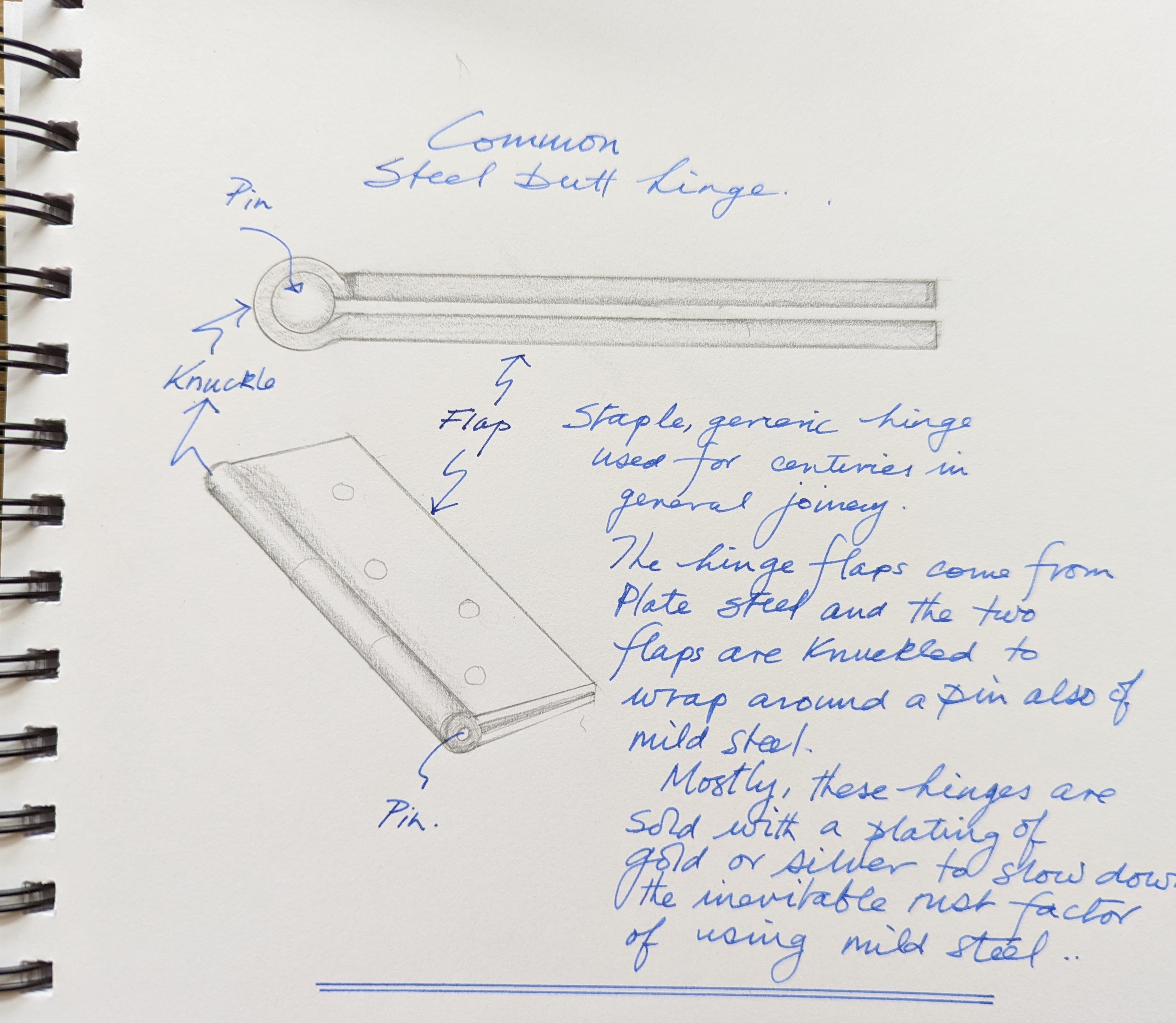

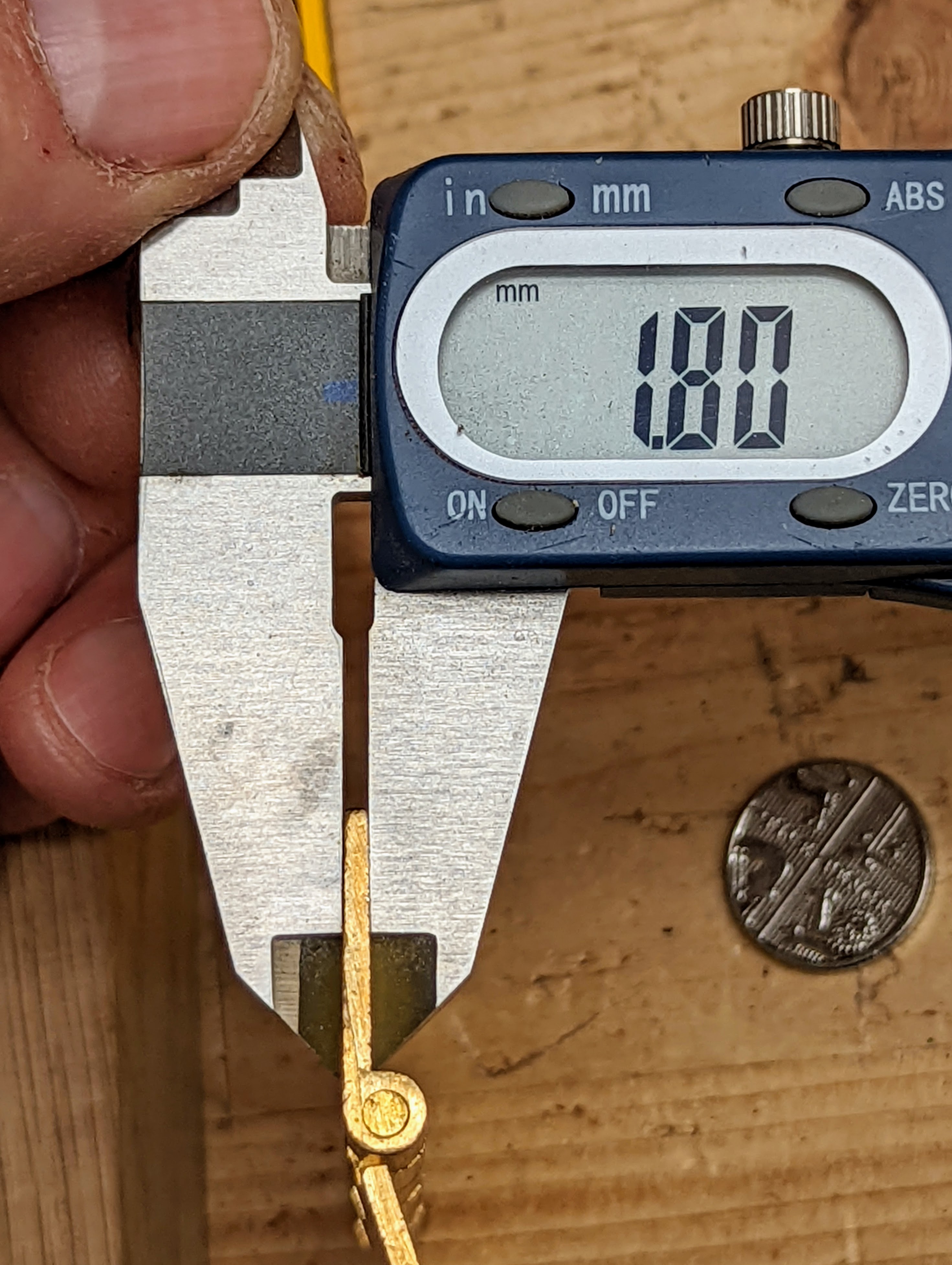

I often found that my students wanted the flap of the hinge perfectly flush with the surrounding wood. The hinge type affects how this will look. The common, steel butt hinge commonly used in hingeing larger doors for say a house or an office room door is stamped out from plate steel and tongues cut into the steel then fold around a central pin we call the hinge pin to interlock the plates or flaps together permanently. These hinges tend to be more utilitarian in function and appearance rather than attractive or decorative. When the hinge is folded to, it often has a large gap with thin steel of say 2-3 mm. The gap between the two flaps when folded can be somewhere around 4 mm. When you close the door shut, the gap will indeed be 3-4 mm if you did set the hinge into a recess where the plate steel lays flush with the surrounding wood. On an internal door, this gap is too big for a refined fit. The advantage of so big a gap is that the wood will usually not bind or stick when the humidity is high. But a more accepted gap will be about 2 mm down to 1 mm.

The thickness of a vintage UK penny was often used as a standard to reach for. Inserting the penny into a gap on a hinged door to make sure that the door was even all the way around the door was often espoused by old-timers who talked of a skilled craftsman leaving a door where the penny would self-hold at any point when the door was closed. That wasn't at all true. I would that wood was that stable. It's not. Wood expands and contracts considerably and especially softwoods such as is used in the manufacture of general house doors.

Recessing hinges in house doors means gauging the hinge gap, the thickness of the flaps and determining what gap you want in the finished hung door. If the gap between the two closed hinge flaps by the knuckle is 4mm, and the flap of the hinge is 2mm thick, when the hinge is in the closed and parallel position as shown, the overall distance from outside flap to outside flap will be 8mm. If you want a gap of 2mm then you will recess both hinges to 3 mm each. However, if you did indeed want a flush appearance to the most visible of the flaps, possibly the door hinge plate, then you can recess this one flush to the door stile wood and recess the doorframe/casing flap to 4 mm to compensate. This less uniform but the practice was quite common enough and joiners I worked with either on-site or at the bench usually set two gauges to establish the depths of the two different flap recesses. When a door was planed undersize by mistake or indeed made undersize by mistake, the joiner wood either not recess one of the hinges or half recess them equally so that at least the hinge had a retentive and registration ability. They might also scotch the hinges.

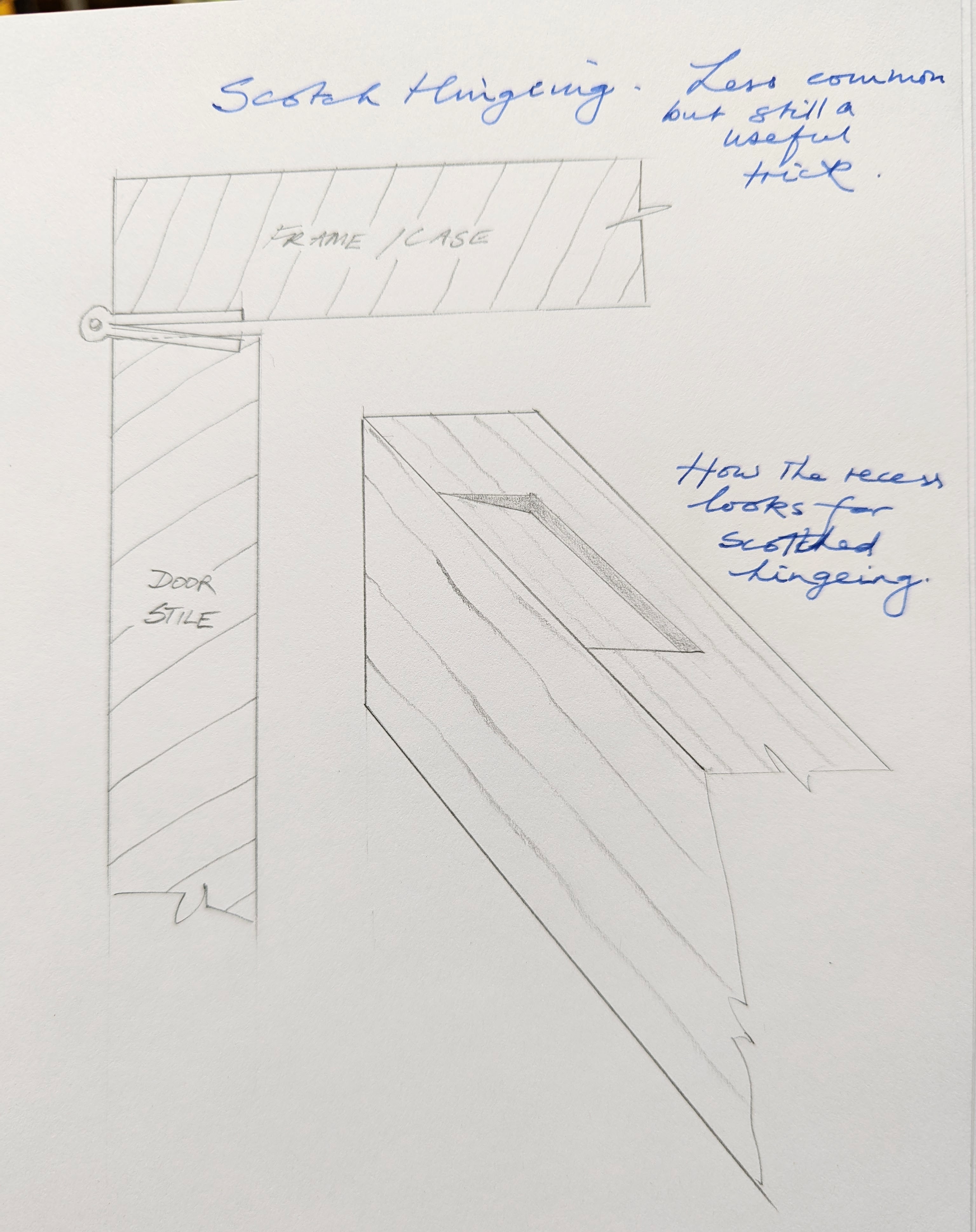

Scotching hinges

Somewhere recently I used a term we use in joinery called 'scotching' the hinges. We usually scotch the hinges when we have made the mistakes described above, but we also use it to offset the knuckle of a hinge so that rather than it being centred on the gap between stile and frame or case we line up the knuckle of the hinge with a side bead in a moulded frame as per drawing above or with a planted cockbead the same size as the knuckle. This feature is a choice decision as part of the workman's endeavour to a perfect resolution of a feature.

In the case of the door being made too small by overzealous planing or making the door undersize in the first place, the scotching is to fix a mistake, error or flawed thinking. Of course, it's not always faulty work. `Doors can shrink considerably if the moisture level in the wood originates at the beginning of making when the wood is at say 15% and then the door goes to its final destination elsewhere and the humidity level is much lower where the wood then shrinks. Such things can and do happen, and it's not just doors either, window sashes can also suffer the same calculation mistakes and you can't usually just throw such units away. Scotching a hinge is to deepen the cut hinge recesses to a steepened incline within the recesses. One hinge recess, the one on the stile of the door or sash if a window, is barely recessed on the outer edge but quite deeply recessed towards the back, internal edge. The opposite recess on the frame or casing is recessed enough to receive the knuckle of the hinge but then recessed partially to register the hinge plate. Additionally, by 'scotching' more, if the door is markedly undersized, you can scotch the hinges to throw the door further over still, to make at least the closing stile look good. I have seen hinge recesses only half cut halfway across so that a bevel midway gives additional leverage via ridge left in the recess which serves to throw the door further over still. Nobody really talks in these realms any more so at least this record will be there if, though doubtfully, it ever comes up.

Let's now talk about gaps. I recall a time in a class when a man insisted that the hinges of his box must lie flush with the surrounding surfaces after recessing. no matter how I tried he insisted that this should be the case also I left him with his intent. Unfortunately, the gap on the hinges, between the two flaps was massive and the plate of the flaps was pathetically thin. When done, his box lid sloped and he had a 4mm gap on the hinge side and zero at the closed side. It looked ugly. He finally understood the principles of calculating the hinge recesses and changed his ideas.

A one- to two-millimeter gap between the rim of a box and the underside of the lid is acceptable though 2 mm is a little too much. I would most likely shoot for 1mm. Why any gap? Wood surface swells first, before the inner wood, as this is the most exposed to the atmosphere and even with finish on it still absorbs though to a lesser degree. Rarely are environments regulated to perfect stability and in most family homes and offices, with an increased volume of occupancy can fluctuate markedly. That means that both the adjoining wood faces can come closer together albeit very fractionally. When it does, the swelling can cause the lid to bind and elevate the lid or door beyond the inner faces of the hinges leaving the box with an open gap on the edge opposite to the hanging side. Our task is to consider this possibility and then too anticipate such things and cater to them. Better the one-mil gap than for pride to say ultra-small or even no gap at all.

Recessed doors too will stick if the gap is insufficient to allow for a swell, even a small one. Again, when in construction you can move for a small gap of a millimeter or so but before applying the finish you should consider its long-term home environment when delivered. Two millimeters is very acceptable but still be prepared to go back and take some shavings off. If the door is recessed on all four edges, then the free edge, the opposite edge to the fixed edge or hinged stile, will be planed with what we call a 'leading edge'. This is where we plane the edge slightly out of square. This is because corner to corner the door measurement is greater than the width of the door. Planing the edge out of square allows for this closure and the outer edge can be left quite tight, a millimeter is a good starting point but it might need more off after housing in the final destiny. Of course, geographically you may not be able to go back to take that shaving. better to take a millimeter off and have a slightly bigger gap on that closing edge.

A face-fixed hinge plate might need no recess. This then relies solely on the screws as permanent locators rather than the recess supported by screws for added security. Door weight and use inevitably lead to slippage eventually and then the door starts to catch.

These images show that the flaps of drawn hinges are often not parallel across the width of the brass but tapered from thicker to thinner to the outside edge.

In general, drawn brass hinges have a consistently good quality though progress seems always capable of making things like hinges thinner and less robust.

Comments ()