Wood Moves, ALways, All ways

I am often troubled by how many woodworkers are surprised by their wood moving after they've recently ripped and planed it true. I understand that this more an ignorance of what they are working with so it is important to discover this reality early on in your woodworking life. This will help to avoid disappointment and ensure successful making as you progress. The reality is that wood will almost always move differently in accordance with the wood type, the level of dryness, the level of surrounding atmospheric moisture, such like that. Truth is, it's going to move by unpredictable amounts in unpredictable ways no matter how good the science is. Science helps a little, not much, it's what science cannot predict that influences our work at the bench. Being in tune with your wood means seeing the issues in the grain; that knot, that swirl in the grain, that medullary ray cell. Hmm! This knowledge comes only by experiencing the wood you work in your zone at your hands and NY your willingness to sometimes be patient, experiment and take risks too. Mostly I see that woodworkers think that that process of size reduction and planing straight somehow stabilises their wood, that once done, the wood should no longer move, but there is no immunity to the disease of wood movement. By disease I mean did-ease. It makes you less at ease. Living with this dis-ease is par for the course. We must learn to live with it and learn to minimise its impact on our work. Unfortunately, there is no permanent fix for something that is always influenced by the weather, the atmosphere, the surrounding conditions and so on. We woodworkers just do our very best. This lack in our knowledge of wood and its properties is usually due to our not realising that the atmosphere surrounding where we live and work affects almost all craft areas by influencing the basic materials we work with. Any spinner of yarns knows about the fibres being spun and how damp, warmth, cold and so on uniquely influences how they work their material. Spinning it is one thing and then too there is the weaving of the said yarn too. It's the same with almost all materials ranging from metals to woods and reeds to rush.

In my world of working wood, the most predictable thing about wood is its unpredictability when it's been ripped, crosscut, planed smooth, squared and trued. We woodworkers soon begin to understand that wood continues to move and distort soon after and long after sawing, after planing and, yes, even after truing we may well need to retrue a distortion that occurs due to the permanent or temporary changes in the atmosphere our work remains in after completion. How many finished pieces of work have you seen with shrinkage cracks or cambers and twists a few weeks, many years and centuries after being made into a finished piece? I've worked its fibres for so long now that I factor in the probability of such movement until I have concluded the joinery. Ideally, I try to conclude my joinery within a few hours of the final dimensioning. It's safer that way. Because of that, I usually get on with the joint making in the continuous flow of working and take the wood from squared stock to joint-making as soon as practicable. Immediately is best! Making this an essential strategy usually means that I ripcut my wood to width and thickness and then leave it close to hand and near the bench until I am ready to surface plane, thickness and true my wood. Joinery does constrain wood in almost all projects but you must have strategies. If you use breadboard ends on a flat panel like a tabletop you must dry it down to as low a moisture content as possible and use M&T joints that allow for expansion and contraction. Recesses for drawers cannot be too tight because they might expand and it can be impossible to open them later if they expand in a damper atmosphere later. Everything from door panels to drawer bottoms are designed to minimise the expanse of shrinkage and expansion. Start considering such examples more critically to better understand the reality woodworkers accepted when they made their projects a hundred and two hundred years ago.

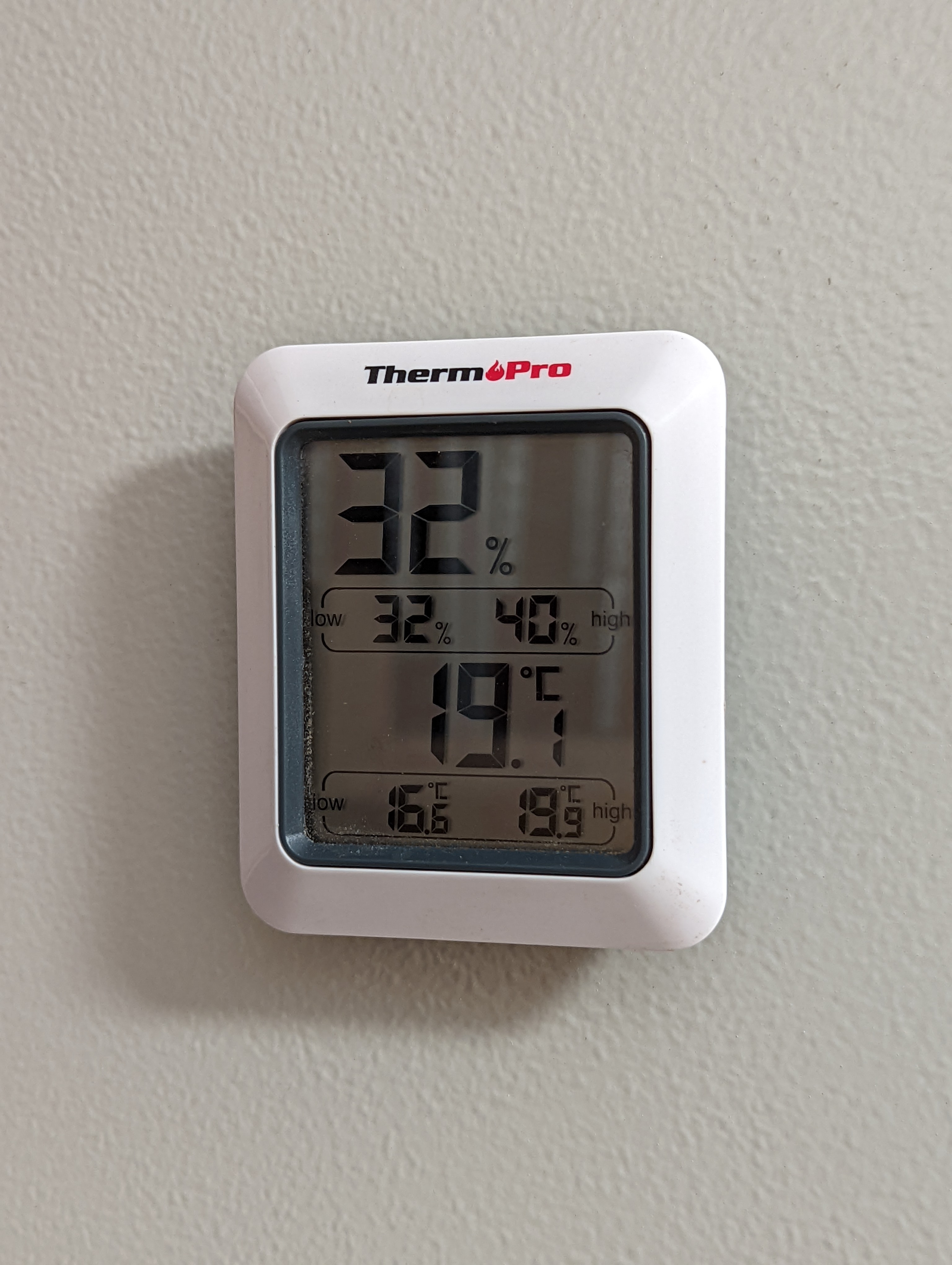

Making my chairs meant that I took the six pieces for the front legs and seat frame in successive batches, sized them and trued them and cut the six mortise and tenon joints and the four housing dadoes in quick succession until I could leave them fully assembled and constrained. Within an hour and a half, they were secured and constrained within their relative partnered piece, unable to ever move again. They will remain so until they are glued together in the final assembly. Guaranteed! So, much better not to finish preparing your wood until you know you can get to the joinery. If you can't do as `I suggested, and you want to prep the wood so that you can dedicate your next work session to joinery, shrink-wrap it as tight as possible or bag it in a plastic bag and seal it tightly. Keep it away from any extremes of weather or atmosphere and esp[ecially if the atmosphere surrounding the wood and workshop is highly changeable. It's a good idea to know what the atmosphere humidity/temperature is anyway. Mine is controlled. 36% seems as good as it gets to me. I rarely have any issues. Oh, and it is always good practice to keep your wood in an environment that is as stable as possible. If you don't have that, I suggest you work on it. At my home garage, I had vast extremes of changeability. Dry-lining the walls and insulating the floor, adding damp-proof membranes, etc have changed everything to make it totally controllable. It's easy enough to add stud walls, insulate them and face them with a material like wood or plasterboard (sheetrock USA). Concrete floors can be more problematic but still doable.

With wood being so sensitive to exchanges of atmospheric moisture levels, some woodworkers make hygrometers out of U-shaped sections of wood, strips of wood and such. The wood curves in high humidity and straightens when the levels fall. They usually just hang somewhere in the shop. But hygrometers are relatively inexpensive, accurate, and smile to read.

Anecdotally: I stored a tabletop from a longleaf pine coffee table I made in Texas from some virgin longleaf pine retrieved from the beams of a demolished factory in the loft of my garage. Prior to this, it had been stored in a storage container in central Texas where summer temperatures would be 40+ C (104 F) In my UK garage the top curved like a banana into a half-inch camber over the three years of storage. That's over a 21" span. In my studio workshop, it released the excess of moisture over three weeks and returned back to the original flatness of when I made it 30 years ago.

Cutting the oak for the dining chairs, my wood remained near-perfectly straight and true and, with parallel cuts made on the bandsaw, I noticed the wood did not curve as each of the long cuts progressed along the length. This is the nightmare of tablesaw enthusiasts because in a split second the curve can tighten onto the blade at the back end and cause kickback as the wood is thrust upwards and often slammed back towards the user and smashing into the face. Even with all of the safety gadgets and gizmos in place, you must always be ready.

Comments ()