Times Change Craft

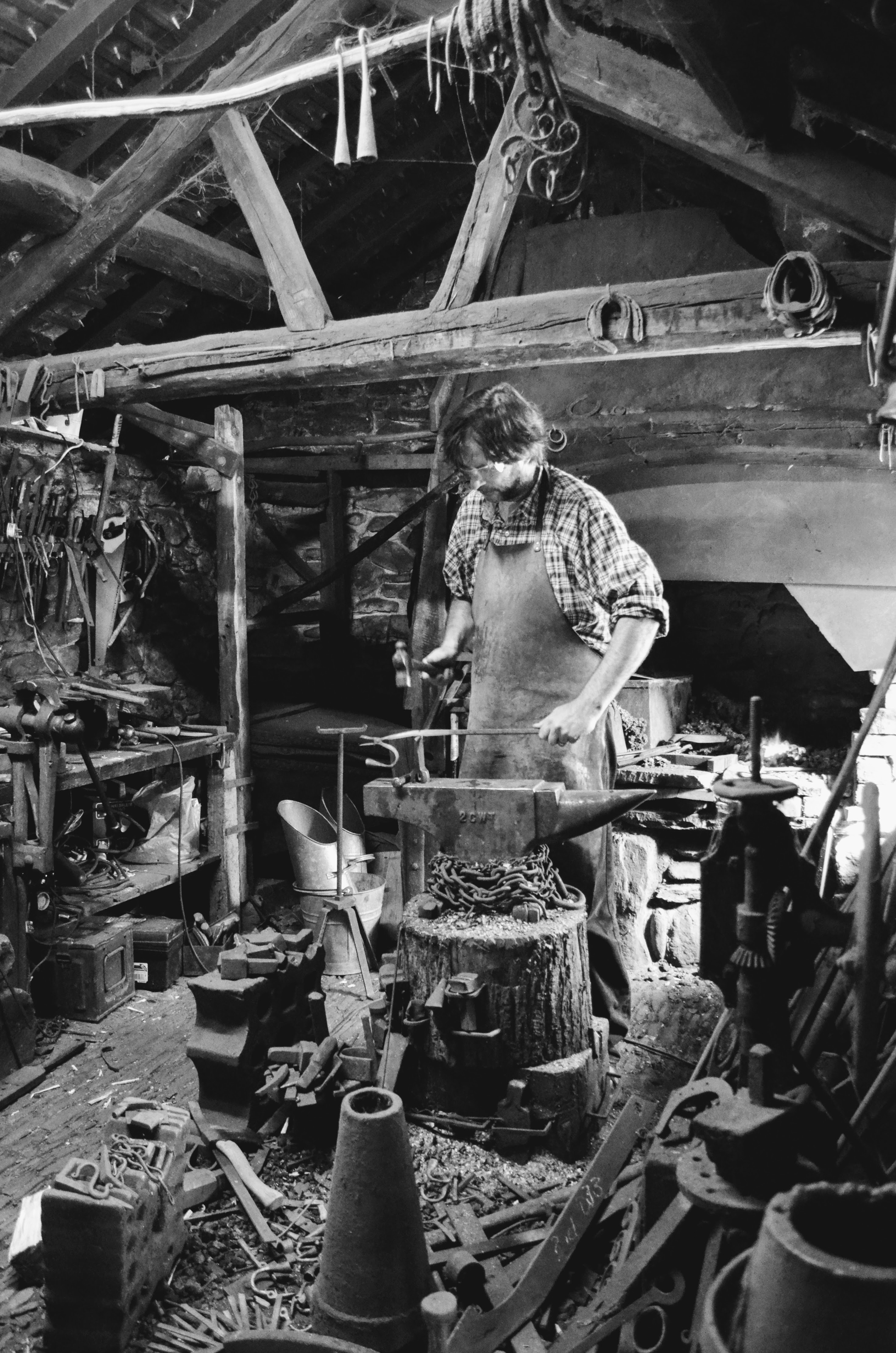

I think we undervalue crafts, now, together with their once-regarded significance in supporting all areas of life. in every quarter of our humanity. If indeed we ever really understood and valued crafts at all in the recent century and more is truly doubtful for most. Why do I say that? Well, I think that people born after a certain date will most likely never have really associated craftworking with the support of agrarian life. But more than that, they never had the opportunity to see or try any real craftworking of any kind beyond perhaps some kind of reenactment. If this is the case, and it is, then they have never been exposed to it in any true and living form. I count myself fortunate. I have! I have lived and worked alongside many practicing artisans and watched them as they worked with me in the same shop or nearby, next door, across the way and such. The art of the blacksmith, the potter, those in my own craft areas of furniture making, joinery, carpentry and general woodworking -- those who adzed and axed beams, formed massive tenons day in and day out, that sort of thing.

I can't really describe what it's like to design a table leg in iron and watch as a blacksmith hammer-sculpts it and then the entire table over the next two weeks or so. I mean, I designed these things to be made for customers from raw steel to hold my woodwork. To see the faces of those buying the commissioned work as a joint endeavour of two diversely different artisans is pure joy! There's the table, the bed, the lamp and leaf, I mean. If you've ever made a dining table to sell for $48,000 you begin to understand that skilled work commands a certain measure of support, yes, but that the art of crafting can be a difficult path to pursue until you catch someone's eye that sees your true worth as a maker and designer. Another I designed in mesquite and steel, a coffee table, I undersold for $5,500. It was stunningly made with hand-cut joinery in steel, peened-over tenons, drawn-out tapers taking a thousand hammer blows.

The art of craftwork is dying out, not being saved, of course. Who is it that can compete with mass-making? If we say it's not dying out we live blinkered by our own ignorance. Historical organisations only express what was and never what is. In my 70 years, each decade has shown me that crafts are significantly diminishing year on year, that we see less of crafting work by each decade's passing. It is indeed unstoppable simply because there is a massive gap now between those that can afford handwork and those that cannot. But it is much more than that. Another gap has gradually caused the great divide and that is the reality of a new generation that has never seen or known the art of it, recognised it for what it is. The generation I speak of never heard the ring of the hammer striking steel, the anvil's ring that followed the strike by a man's arm and hand. By that I mean we fail to see and understand the fuller value in the physicality of manual working as today's microcosm of what once universally supported all areas of life throughout the world.

Through the decades we have seen handwork projected into a mini industrial world as a supplant of an industrial process: think something along the lines of a knitting machine, slip-casting clay mouldings into an inner and outer latex mould for slip-cast pots and castings, or copy-lathe turning for woodturning, and then of course, in my own field, the complete takeover of woodworking by, albeit downsized, industrial machine methods where handwork is literally minimised or even eliminated altogether. This being so, we see deskilling as a more advanced societal improvement whereas the skilled work we once knew and recognised as such, respected, depended on, was the truly skilled work of the masses instead of the now isolated skilled work of the very, very few. Translating craftwork into industrial work using mass-making methods should be recognised for what it is in relation to what it once was and that is simply a means of producing cheap, disposable products to generally at least feed the consumerism as the evolved pandemic in all of us. It also made even more money for the owners of wage-slave workers.

I'm often told by media watchers -- exponents and such like -- you know, the informed, and then too those influenced by entertainment makers and presenters, that "They're bringing crafts back!" The sentence always has a cheery, affirming sort of smile warranting the exclamation mark, italics and bold text too. "They're", means the government, education departments and so on of course, and not really individuals training on a one-to-one basis. They're kindly trying to encourage me and think if we just say it and believe this to be the case then it will happen. Of course, "they're" not. The 'They're' is not that kind of entity. The 'they're' is more about their bums-on-seats economy only. The other one I hear, after asking me what I "do?" is to say, "Oh, I love craft shows and I love living history museums where they show the 'old school' ways of doing things." I think people sort of hope crafts don't die out altogether and comfort themselves by somehow being convinced that the crafts are being restored, kept alive. But saying it doesn't really mean much along those lines at all. It's surprising how many associate woodworking with the recent so-called green woodworking movement of the latter couple or three decades. It's nice to sit with friends by a wood fire and carve wooden spoons with a purpose-made knife, an art if you will, very beautiful sometimes, or even set up a spring pole lathe to turn a bowl or a few chair legs, it's another thing to do it as a way to make a living and especially long term. Reenactment too can be interesting and if well done might even feel more real in the field, so to speak. It does not bring back the reality of artisans making to live by their hands as in say chair bodging or spinning and weaving. Yes, there can and will be some vestige of what once was, perhaps, but crafts can never return as a way of life without a total collapse of globalism, economy, and its bed-partner, consumerism simply because handwork can never keep pace with consumerists and their ever-exhausting demands.

. . . his hammer lay flat

to the anvil's table where no more

steel formed the art of his hand

for no man came to replace him . . .'

Except for those occasional small pockets of individualism by some less compliant individuals and tiny groups, crafting of every type is mainly supported as a hobby or a highly specialised art form -- think remnant, skilled blacksmith replicating authentic ironwork, stonemason and woodcarver restoring buildings and no longer at the beginning of a new cathedral taking centuries yet to build and amongst a hundred more in each craft on the one building. Even then, today, you must recognise that much of this work can at least be roughed out by machines driven by a computer system somewhere along the line and even on a different continent. Perhaps me too, making my rocking chair and other such individual and special pieces. We, crafting artisans, are a dying breed. Very few can work effectively fast and efficiently enough by hand to make a living simply because the drive that drives us changed. In recent years I watched several furniture makers making that spent 50% of their day perched atop a barstool staring at a device. "Fraid this doesn't get the project from the bench to the customer and the customer rarely likes to pay for a Googler. Even the bijou studio manufacturers of hand tools, woven ware, pottery and so on, rely heavily on production methods and ultra-high prices to make it a way of life. So why lean in the direction of mastering a skill?

Just as cultures around the world have died to the support of skilled craft by buying into mass-made and in most cases disposable goods, so too has the culture of making become obsolete enough to be actually lost. As the art of handwork continues to decline in and of itself, it is most likely that you will not know anyone that makes by using their more long-term, established skill in handwork. Therefore, we will indeed see the finality of artisan making even in those areas of unique communities that might retain some vestige of an ancient tradition. Any craft area that we might see some kind of craft revival, wooden spoon making with bent knives, froes for splitting and axes, will be the result of an individual self-studying an art form for personal interest, self-improvement, etc. As a way of making a living, most to make anywhere near a living wage and those that do are the ones that persuade others to learn from them on a course in the woodlands somewhere. Most are very unlikely to find a market for their treenware, even if one or two of them cand do sell a wooden spoon for £50. The retentive value will be in that personal interest the individuals have for making using raw wood for free from the woodland, spending time there in earthy environs, nature, and not because the public sees what is made as a convenient resource from a local crafting artisan. As long as IKEA sells a solid beech spoon and spatula for £1 and 12 of their meatball lunches and coffee for a fiver, people will keep going to the great cathedral of consumerism. In most cases, I see crafts now continuing on a far lesser level if they are developed as a hobby as a personal interest. People with some level of additional support from family members as main earners and those with disposable income and disposable time to invest in support of their chosen craft. Beyond that, craft has indeed become a lost means by which we make and live. For me, I am just thankful that woodworking, furniture designing and making, woodturning, carpentry and such, have always been my chosen way of life. I do see furniture designing and making alongside those other individual crafting artisans where it is still viable to make and sell pieces of distinctive design and flair to be of creative interest to buyers. Those of us who consider woodworking as a lifestyle rather than anything that could be called conventional as with work that has replaced and displaced craft and handwork. Across from me is a man that makes many types of components for cars. It's a small compact business with different machines he operates from his computer. He loads the machine with metal blanks every few hours and when he comes back an hour or two later there are the multidimensional components pristinely shiny and ready to ship. He loves the work he does in the same way we woodworkers do. We do it only because we love it and then we can also make income from what we make too.

The important things I see and feel more now is to see crafts as a way out. Woodworking is especially good and doable for this and hand tools have been the most inclusive of all ways simply because you need so little to do it and you can accumulate the few tools you need over a period and end up with a way of easing the pressures of life without a garage full of machines or even one. In its new and fascinating multidimensionality, hand tool woodworking has an appeal that stretches around the globe. Yes, some are highly privileged and assume everyone else either has the same or they just need to work smarter to get them. But the differences across borders are often chalk and cheese. For me, hand tool woodworking is healing for the majority who do it, it's therapy for others and then recovery from many different types of abuses. For some, maybe with carpal tunnel syndrome, those with autism, its alternative way of working that gives a measure of pure relief and so too for those with jobs that bore them to tears and are filled with tedium. Listing the changed reasons is massive, massive. It caters to shifts in our ever-shifting culture to pave a way to betterment. My reasons too have changed. As a perpetual maker, I began to shift, not from making but to expand in my making to teaching and training, writing, drawing and designing. I never abandoned making to teach and make videos alone, I simply added work I believed in to expand my vision and to make my craft as inclusive as possible to men, women and children with and without struggles of a million kinds.

Comments ()