Beech Wood: Come to Know It

With eight chairs to make, I picked out my beech carefully for minimizing my stock preparation work in rip-cutting and hand planing all the surfaces straight and true, square, smooth, etc; better off the plane by a thousand times than off sandpaper. My system is quick and efficient and each stick of my chair wood once rough-cut to size on the bandsaw takes about ten minutes to complete. With 40 sections per chair and eight chairs, that's 320 pieces and that then is not far off 30 hours of stock preparation so I would say I have a couple of weeks of chairmaking I'm headed into. Nope, I don't own a tablesaw nor a planer anymore. I don't own a mortising machine or a chopsaw either, neither do I want these things. I will keep stronger and healthier, more interested and happier without them. If I do run out of time or steam, I might get help but it will not be from any machine beyond my bandsaw.

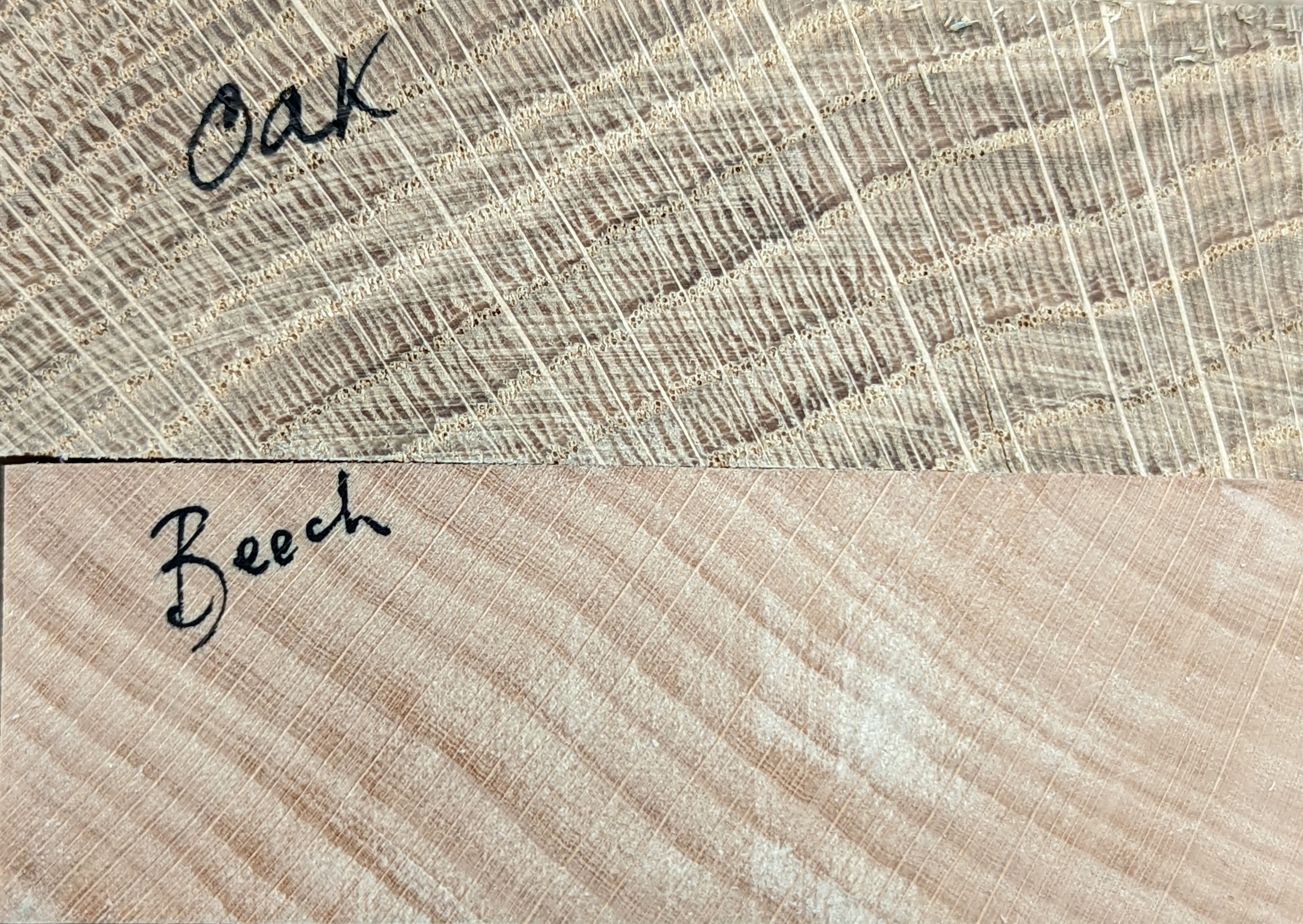

Beech is a close-grained hardwood with certain characteristic elements but it's a fairly plain wood without a lot of character unless it has become diseased by something like a fungal attack. The wood works very readily with hand tools and by machine methods and I find it consistently well with hand tools and planes to a super-smooth level with bench planes. That said, it is one of those woods that every so often results in isolated areas of surface tear-out. This occurs when the grain alters direction even by the slightest amount. In most woods, you can simply plane in the opposite direction to correct the flaw, not usually so with beech. Plane the opposite way might well correct that patch but then both sides of it will tear instead. The best response is to reach for the #80 scraper followed by a card scraper. This will always correct any issues of torn wood in any wood including beech. In 95% of the work on beech, the plane will do everything you need to do.

Beech is a tight-grained wood of even density throughout its fibres and without any noticeable difference between the early and late aspects of the growth rings you get with many temperate woods. Planing oak at a tangent will often result in distinct sound changes as you plane it, together with visual 'stepping' in the surface where a percentage of each growth ring wood compresses and springs back under the pressure of the cutting edge of the plane. This often happens with softwoods too. Many of the softwoods, like European redwood, have greater distinction of hard and soft wood to every growth ring, hence the darker later summer and winter growth against the more spongy fibre in the early aspect of the growth ring adjacent to it. No such thing is so evident with beech, so planing the upper sloped back of my back chair legs to give it its angled back resulted in an absolute glass-like smoothness along the full length. The one thing I might say is that this wood is absolutely intolerant of dull tool edges so continuing to plane once the edge is starting to dull will result in rounded faces as the plane takes any path of least resistance. My advice is not to wait until dull but to sharpen much more than you might normally allow, consider twice as often as not being too much.

You will find the consistent density of beech makes chisel work much different to most other woods. The fibres seem more reluctant to part away from one another under hand pressures in work such as pare cutting and even chopping. This 'clinginess' is unusual in most other woods but not problematic. In mortising, it feels as though the walls hold to the wood more and you can see where the fibres are pulled apart by the chisel chops rather than the split-off you would get with all other hardwoods and then some of the pines. Because it is a hardwood and more dense than other temperate hardwoods we might expect similar properties to say maple, ash. cherry, walnut and oak but that is not the case at all. I think it's fair to say just take your time and think about the new differences to be experienced. This is where we increase and store the knowledge we gain as our personal understanding of a wood species. A personal retrieval system as a library of wood textures and characteristics if you will.

Beech seems always to be less likely to split than say oak. It's hard to say why this is less so but the tenons I fitted into mortises seemed fine when really quite tight and what I might consider much too tight in oak, for instance. In chair-making this is ideal but then I consider the glueability less reliable and especially when super smooth. As this is my opinion, I might suggest 'toothing' the tenon faces, a process we use in veneering where we create cross-hatching to the meeting faces with a plane called a toothing plane. We can do this with a tenon saw, by taking side swipes with the teeth across the faces of the tenons two or three times. Toothing does two things, one, it actually roughens the surfaces to increase the surface size -- think highs and lows as in mountains and valleys covering the same square acreage as say a flat field. The ups and downs result in a greater surface area than a flat plain with the `addition of a rougher surface being filled with glue too. Two, it gives somewhere for the glue to go in assembly rather than the glue being pushed off the faces of the tenons as the tenon enters the mortise leaving very little glue there to make a positive bond.

As it is with many aspects of woodworking, no one cut on one wood type is exactly the same in another. Every wood is different under the cutting edges of chisels, planes and saws and beech is a wood that has a holding, grabbing, pulling element to it whereby the plane and saw seem to more drag than part off or, as in the case of oak, for instance, spring away from the cutting edge in its severance. The importance of understanding such things for yourself leads to the intimate knowledge we need as woodworkers and thereby leads me to speak yet once more of the difference between those who use hand tools to work their wood and the wood machinists. Not one and the same and not to be in any way confused. Separating wood on the bandsaw can in no way be compared to cutting it with handsaws. Pushing the wood into a steady rotation with thousands of cuts per minute per foot run is simply not the same as pushing the saw into the wood. With hand tool methods, you are capably and constantly evaluating the wood's essential and distinguishing attributes. These are the elements of its structure, fibrosity, resilience, resistance and so on, and therein lies the key difference between hand methods of working wood and machining wood. With one you constantly receive and process the information as you push the tool into the wood that tells you about the wood you are cutting as well as the hand tool you use and then too, not to be dismissed at all, your own body in how it's working, you are working it and how best to control all three. This feedback is not available or accessible in any other way.

Comments ()