Grain Ramblings

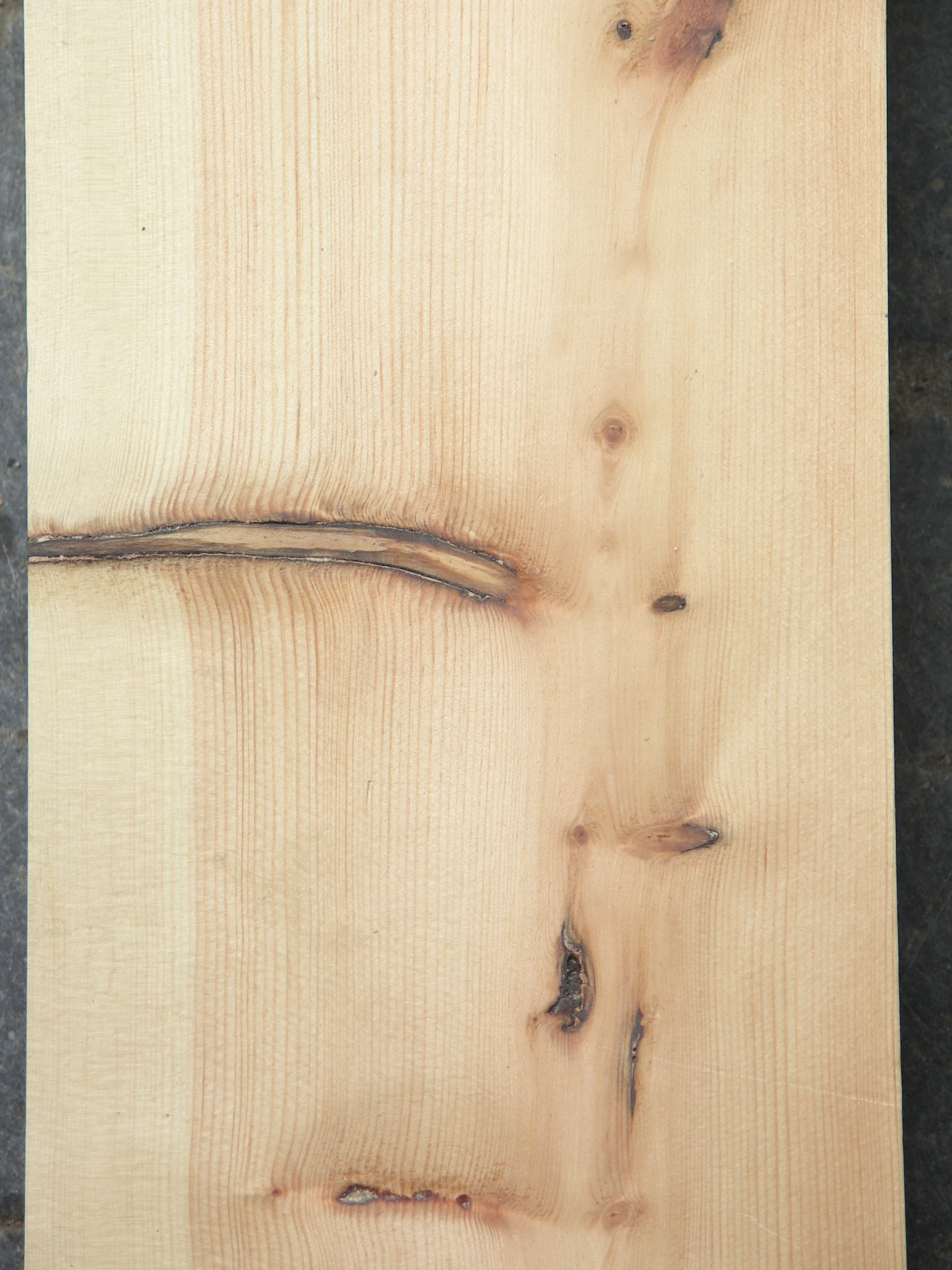

I think grain is a deceptive substance, unpredictable and predictable in both its unpredictability and its predictability. When you least expect it, it nose dives, in a split cut, half the tenon or dovetail disappears. When the grain circumnavigates a knot and we think it will never plane on one side or the other of it the grain comes out smoother than silk. Of course, the exact opposite happens too. If we look at wood as a rectangular block, with surface-treated faces made level, straight and square, or shaped and left smooth, and with or without texture, without considering its inner workings of cells and fibres, strands and a mass of chemistry, we might as well think of it more as a section of plastic or other material and even an engineered material such as fibreboard which is also made up of mixed materials a large percentage of which is pulverised wood.

Unlike other materials created to emulate wood, wood is a hygroscopic material that takes up and releases moisture in accordance with the surrounding moisture levels suspended in the atmosphere. High levels of water, humidity, is readily absorbed into wood, and when this happens the wood expands in its width and thickness. Conversely, low levels of atmospheric moisture will lower the level of moisture held in the wood fibres. With absorption and release comes expansion in the width and thickness of wood, or shrinkage, all according to moisture content. And here comes yet another sphere of unpredictability. In the evening you left your newly planed and trued wood on the bench dead flat and the following morning it looked more like a banana. Waah!

I'm sitting in a cafe where I mostly write and all of the tables are dead flat. Running my fingers over the tabletops, they are smooth and feel fine. The tables, about fifty of them, are made from solid oak and I think that they look nice but would be better unstained. Considering the abuse cafe tables get from spillage, these tables hold up. Not one of them shows any sign of a cracking or separation in the narrow laminations and this is the reason they go for narrow laminations rather than wide boards. For mass-making, laminating tabletops ensures that the tables will stay flat, but more than that, any attempt at rebellion from one piece is countered by the dominance of the masses either side. Laminating this way holds and constrains any proclivity to distort through the absorption and release of moisture in the wood. Of course, a waterborne, water-based finish as a surface treatment basically shrinkwraps the wood throughout with its plastic-based resin coat. Cafe tables of this type are always finished as well on the underside of the table as the table's topside. The corners are never sharp and always rounded. This is no different when using paint. Why? Varnishes and paints stretch in their shrinkability. This seems a false dichotomy. Does it stretch or does it shrink? Can it do both?

Applying most wood finishes, whether clear or pigmented, begins by placing the material on the surface via paintbrush, paint roller or spray. I say place because that's what painting and varnishing does. The layers are built up and in almost all cases adhere to one another. The exception is shellac, which capably dissolves the first coat into the second and subsequent coats resulting in a single coat applied several times. These finishes dry and the surface becomes taut through shrinkage. If the corners are sharp-edged and 90-degrees one to the other the applied finish becomes super thin at that point and breaks or parts off into discontinuity between any adjacent surfaces along these corners. Rounding the corners even minimally allows the finish to wrap around the corner as a continuous unbroken film.

Many woods benefit from the different ways the boards are slabbed from the tree stem (trunk). Quartersaw wood offers greater stability because the resultant wood is best able to accept increases and decreases of moisture in equal measure from both sides or faces of the wood; this has much to do with wood density (specific gravity) levels, period and division of annular growth (earlywood and latewood porosity) and the arrangements or grain presentation of cells. The resistance in certain cut types as in plainsawn can and often differs due to the obliqueness of the growth rings, etc, and the uptake of moisture content be that via direct water or water vapour as in relative humidity, etc.

On the oak cafe tables, I noticed how the plainsawn wood seemed to remain smoother and more even than on the quartersawn which had the hint of a washboard effect.

Of course, oak being coarse-grained and of more variable density surrounding the growth rings, the surface texturing tends to be more diverse and exaggerated. Other hardwoods such as beech, ash walnut and so on give a consistent surface smoothness.

Comments ()