My hands, My Tools, My Life

When I returned to live in the UK after living in Texas for two decades, I was surprised to take over a huge room in the National Trust's Penrhyn Castle. I began teaching my hands-on classes there and then began outreach online from the same place I taught one-on-one. There I had bags of room, enough for 20 students with benches and tools and then two or three apprentices too. After five years there, it was time to move and I moved south to England and again the move felt temporary. What did feel good was the garage workshop I set up temporarily at the house I rented back then. It was an average UK single car garage size. No spare room but good enough to make in. Long story short, we created my make-space studio to simplify videoing my work and working to these proportions. Quite the downsize from my Welsh Castle.

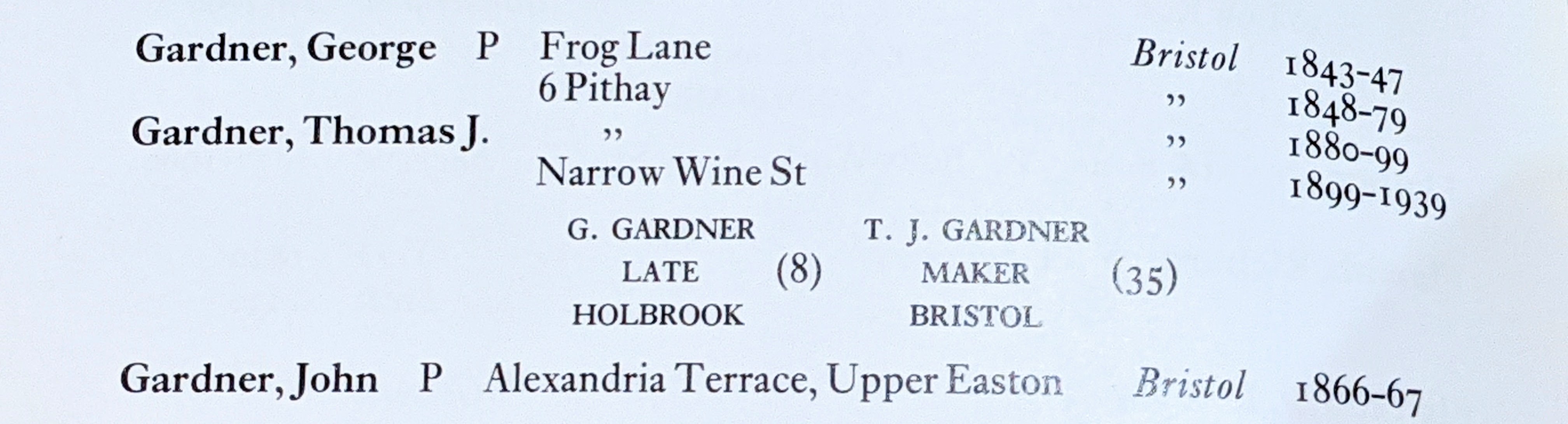

Downsizing behind my bench over recent years didn't mean reducing the number of tools I own, might use or keep for different reasons in the future. I own a couple of hundred planes, maybe three or more, I don't count them but they are identified and categorised for retrieval. The largest category for me is the gathering of moulding planes I've accumulated over a number of decades. If you use and collect moulding planes you will need in excess of 300 of these alone just to accommodate every shape type used to create moulded stock (sticking) and then plus some. Not all of my planes have some particular meaning, but many do.

When you hold a plane made in the last quarter of the 1700s, the gravitas of a family of plane makers can hit you and even flood over you with the thoughts that back in the 1700s and on through a century and a half that followed, planemakers and users preceded the mass-making era we know today with hand made mouldings that came from simple and complex hand planes made from beech and fruitwoods. These early makers, men like John Cox a plane maker from1770 to 1801, William Moss, also of the same era, and Benjamin Froggat too, all famed makers of Birmingham, England, left a legacy of hand-made planes for us to glean from. That sense of serious making, a period when a plane meant making an actual living for the owner and the maker and the user with what you made, bought to make with and held in your hands what would create moulds for the next hundred years even in combined runs of a hundred miles in length. The waxed sole that lengthened the plane's life, the sense of purpose and use, and then too a memory in each one somewhere along the line, bespeak of a whole world of sheer hard work.

Vintage plough planes can be converted and adapted for another purpose in our new age of redundant planes. Finding new use by conversion is not uncommon, never was. Wooden plough planes are usually fully functional but they can readily become another tool type. Wooden router planes came from plough plane irons and would usually take a 1/2" cutter wedged to a 50-degree incline.

Cannibalising tools was once commonplace and is not an uncommon practice today for some of us searching for solutions. Especially is this so when you find a second one to sit alongside one you already own. It was common for a plough plane iron to be used in a wooden router plane body and then be interchanged temporarily or permanently. And then there is repurposing steel alongside the wood from say a beech plane. When you're looking for a plough plane to cut your drawer bottom grooves, search for a drawer groove plane too. I just bought one for £16 with a 1/4" cutting iron. It could make a router cutter for a plane.

I rehoused my moulding planes into a wall of my study. Somehow, moulding planes have a unique quality perpetuated by my culture, a culture which had nothing to do with their shape originations but a culture more than any other that made hundreds of thousands of planes that created the mould shapes from Greek and Roman concepts of design. The ogees, astragals, ovolos, torus, scotias all in many sizes came from wooden moulding planes we developed to replicate in just about every wooden form you can imagine. I put them there in my wall because they serve as a good reminder of where we came from in the pre-power-router days. They inspire me but not because I like classical mouldings or classicism at all. I quite dislike pretension in any form but I also see how the Greek and Roman principles and styles were used to create a certain regulation of form to constrain and restrain a harmony towards recognised standards and forms of artisanry. Standardising shapes of replication meant fixing the expectations. My work does not usually include too many moulds, though `I do like them for picture frames and the like. Why? Not really too sure. I see the purpose in them when used in the right place and by a limited amount. But they can be cluttery and dust-collectorish when every edge to a table edge and shelf corner becomes an astragal or an ogee just because someone bought a power router and a series of router bits. They are used very prolifically by power router owners who enthusiastically find something to do with equipment that might otherwise have very little valid purpose, I think.

Stanley and Record invented and made their own types of combination planes in an attempt to replace the hundreds of wooden planes needed in a joiner's workshop. They never did, of course, but it was a bold and noble attempt. The dedicated profiles of wooden moulding planes meant instant accessibility to the exact plane, simply by the choosing. Combination planes, on the other hand, were fiddley to set up and the outcome often resulted in torn out grain somewhere or everywhere along the stick, rather than the continuous and decent mould guaranteed by wooden moulding planes. I have yet to come across a boxed set of bits from a combination plane that wasn't in pristine original condition with the bits remaining unsharpened from the original manufacturers factorial making. Why? They were mostly never ever used. Why? They just did not work well at all. ` Whereas many were indeed sold over a period of time, and the hope was that the small box of mould-shaped cutters covering every shape and size (not really) would eventually be got used to, they never did!

Few planes match the abject beauty that comes from a row of moulding planes. I think this to be especially so from those planes worked for decades and even centuries. They seem to glisten and glint from that last evening light just before the light be dimmed and the door closed, as the parting glimpse of a man that knew them intimately by the working of them left them to rest. Each had its nuance -- a point where a shaving stuck became a log-jamming concertina of folds that led to a full-on jam. By a single change of pitch in the minutest of measures, he picked up on the changed sound and in a split second lifted the plane from the wood to preempt the jam. These unmeasured and unwritten details were never recorded anywhere, yet they were commonplace to every man that closed the workshop door as he left for home over a period of 150 years. Then too, there were the smells of linseed oil mixed with the oak and the Brazillian mahogany, the pines of different sorts that filled the air and wafted towards the door with the door's gentle pulling. Those shavings in the unswept corners of the workshop floor, the ones that stirred silently and unseen to settle down to stillness for the night, would tell many a story of a man and boy tugging and pushing at planes that made the mile upon mile of moulded stock for the homes of the rich and powerful and, well, pretentious, dare I say. But without the well-to-do of those earlier Victorian and Georgian and Edwardian ages, the honest work of a hard-working man and an artisan might not so exist in the fine levels that they do. Scandinavia may have its distinct style of simplicity, but held within the hallowed halls of British architecture is the attempt at Greek and Roman classicism that somehow exalted the owners of such work to an upper class, beyond the man that made such things. On the one hand, you had the able, the other the enabler. The enabler never made a thing but was known to have class by its owning where, on the other hand, by the hand, his hand, a maker remains for the main part a complete, anonymous unknown.

I often pull down a plane from the lot and feel for the heart of the man that used it and then too the man that made it. `It was indeed fine, fine work, the making of moulding planes using only hand methods and then too the bench planes, but perhaps the art of the plane maker is less so fine these days. Mother planes were and are extraordinarily special planes. You can tell them by their shape for it was the mother plane that 'gave birth' to a thousand others, the ones that in general line my shelves. Mother planes created the exact opposite profiles to the moulding planes and moulded the edges of a length or 'stick' of wood to faithfully create a reverse that ultimately resulted in standard moulding plane blanks. These mother planes were diligently cared for to remain true to the course of making exactness as a constant. The geometry of shape was critical to the classic shaping and proportion and so exacting was this that a maker in Perth or Aberdeen or Glasgow in Scotland could marry his work seamlessly to a maker in London, Birmingham and Manchester, south beyond her borders. Such classic shapes are no longer the mainstay and source of crafting artisans who might earn their livings from their use as in times past but more the classicist of today's collector/user who simply likes to own working sets alongside individual planes. For there are one or two makers who adopted their making as an extension of their woodworking to become modern makers. Hard to imagine, but from the hundreds of makers in the 1800s through 1900s, less than a handful survive.

The transition from the truly dependent artisan plane maker of the 18th and 19th centuries are long gone. That sweated labour, often by candlelight, is not the scene nor need of today's maker, nor is the competition from like makers a driving energy either. The demand may be limited but there are enough woodworkers out there wanting to own a handful of hand-made planes even if much of the work can now come from a CNC machine working, in tandem with other power equipment. Profiles copying the classic shapes are now made mostly in regions of Asia, some Europe and then a few in North America. They come in the form of appliquéd tungsten carbide anchored to steel roundstock to satisfy the demands of those using highly powered router machines that still demand the same classical shapes. I wonder, no, may it never be, but, yes, I just wonder, as I close my workshop door and the shavings gently stir by its closing, will someone somewhere in our post-modern world close the plastic lid on the plastic bases filled with two dozen tungsten carbide tipped router cutters, neatly aligned in a hard plastic stand, feel what I just felt as I closed my workshop tonight?

Comments ()