Ramblings again

I'm glad that the Sharpening Narrow Blades article from last week went well for everyone. A questioner asked me about the difference between hand sharpening freehand and using a guide to get the angle as in a more recognisable wheel-supported Eclipse type; whether the cutting edge was different or whether `I could maybe customise the outcome for a particular type of cut. Two main differences are the outcome I always strive for that are important to me. Whereas square ends should never be allowed to drift too far to the left or right resulting in a skew, it is not so critical as many might think. Freehand can even indulge a skew a little for good reason, even on or especially on narrower chisels where there could be a benefit to it for an internal corner, say, where the pins and tails are ultra-small and rely on as much internal precision as possible for full connection. My first benefit is the speed of sharpening free hand. It takes me twenty times faster to where I want to be and back in the zone of making to make me efficient throughout my work. My ability to freehand gave me the edge over those using machine-only methods in many key areas like inlaying small sections, hinge recesses, truing up the fit of a drawer or a door into its opening, even cutting dovetails that were not on a big scale but still essential on one-off production pieces like say my TV stand here.

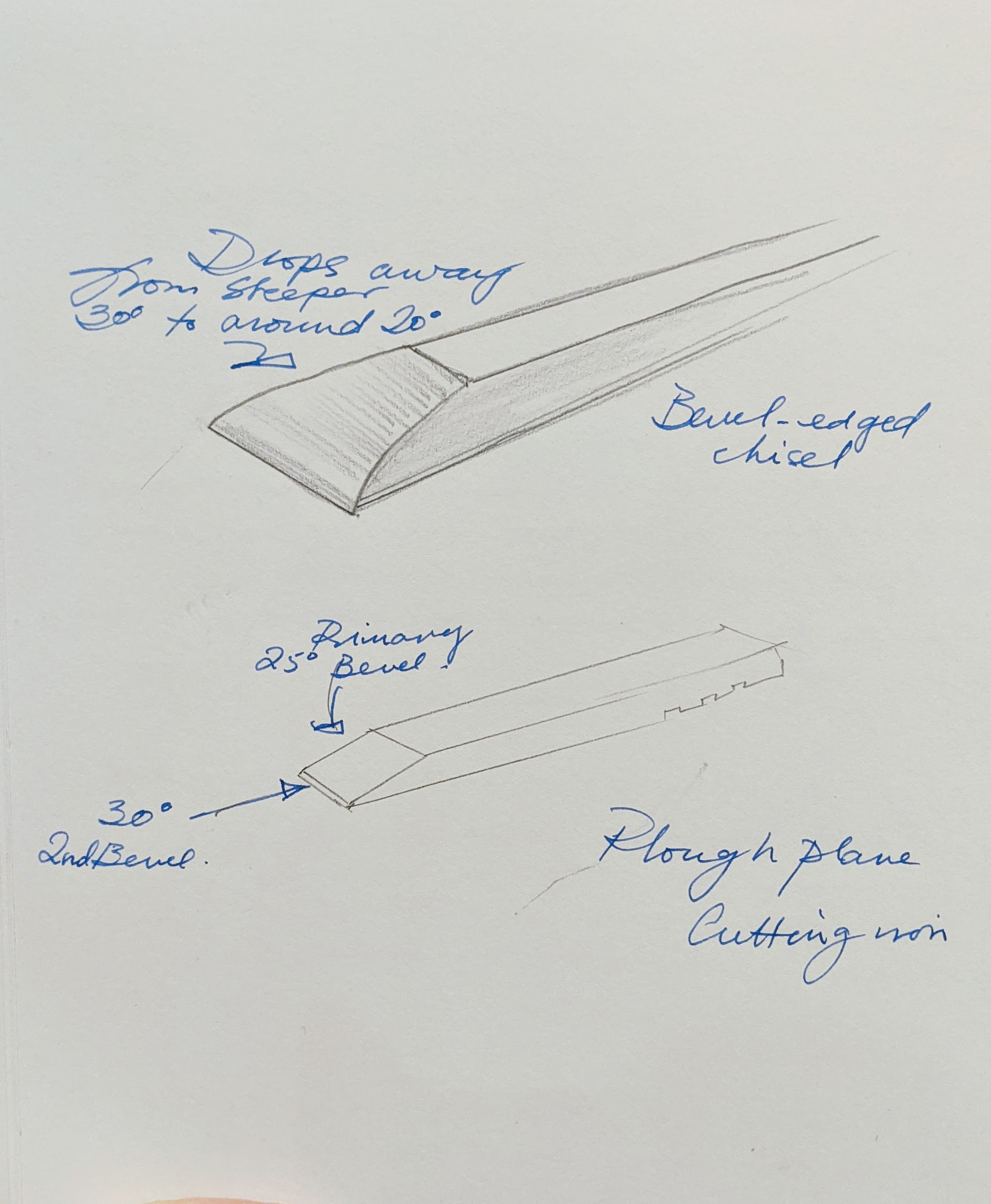

Then there is the type of bevel I love, the long camber from around 30-degrees at the cutting that drops to a 20 in a continuous, elliptical quadrant-bevel. No step change and no resultant stopping yet no changes in quality of cut whatsoever. In my world of making and making all day long to sell my work, these simple steps freed up my time by a significant amount. Though many people are not on that type of production schedule, they are often time-strapped and simple procedures like this can free up fifteen minutes in an hour if adopted. I think I never saw the men I worked under or with using any kind of guide. But I do also think that there is a place for it too. Training wheels, mostly. Watching people set up their guides is often painful to me. I think mostly it's because they are just a few steps away from mastering what it takes to be competent free-handers; just a few periods of the self-correction it takes to establish what you need to freehand your sharpening forever and a few slants here and there is part of the discipline it takes to become super-efficient.

So, why did I design my jig for a two-bevel cutting edge? These smaller blades are difficult to freehand and the major bevel being taken down first gets the bulk of the metal out of the way and establishes the squareness a plough plane needs for squared-off groove bottoms. Narrow chisels too soon go off course simply because of the narrow width and the lack of resistance you get with wider tool blades. Once done, you can sharpen several times at the 30-degree only position then go back in to take the main bevel back down to the cutting edge to start over. That's more than likely every two years on something like a 10mm plough plane cutter.

I guess it mostly helps to counter the early disappointments for many woodworkers and not just those new to the craft. More than that though, here I am, in the saddle, passing on my knowledge and skills in the realness of life and living in woodworking and I can't say that I too don't drift now and then and for a while. It is a quick and guaranteed solution to a problem. I like that.

I'm not too interested or impressed by scientific proofs of academics of my personal efficacy in working here at the bench. They rarely off too much to us of much value because our knowledge at the bench, in the vise, day to day and long term is mostly experiential. My settings of the cap iron, distances from the cutting edge, the depth of cut, the slight skew of the plane to the left, to the right, unskewed square-on, things like that, change the science of it second by second and minute by minute. What makes these micro and macro adjustments work cannot litererally be evaluated or measured by any degree of accuracy; my adjusting becomes incredibly accurate even though nothing I can do can actually measure what `I am actually doing to achieve such perfect pitch. That's why the science doesn't keep up with craftwork too often. Currently, at least, it cannot measure the exchanges we make there at the bench, wood in the vise, tool in the hand, switching and changing as we acknowledge resistance at every point of contact.

The two ways of knowing both have their own levels of importance, one is academic, the other, experiential. In my world, the effect of making with tools in the hands is worth a million times more than mere head knowledge. And it's this too that makes the difference between a machinist assembler and a maker of parts using your whole body and mind to make. Experiential means to climb a mountain or ride a bike on a journey beats watching a video or reading a travel mag. That's about as close as it gets, and my planing yew or cherry and walnut is a constant transmission of wood and tool properties that can never be described or merely watched. All I need the words written for are to say that cherry, yew and walnut all plane in radically different ways but there is no substitute for knowing this at the deeper level of actually planing, sawing, chiseling, axing splitting and shaping and shaving the wood with two dozen or so tool types. My working and the way of it needs no validation by any third party simply because the outcome of my work, how I work and the methods I use are so productive, effective and efficient. They are proven by the outcome of made things through many centuries. Also, I know the difference between wooden and metal-bodied planes by my working of them on the wood. If I can stimulate enough woodworkers to experiment at the bench with one bought on eBay or at a garage sale, I am happy. Do I have to tell them then about a Japanese hand plane or a European one, both of wood? No, not really. What of a North American mass-made one, high-end or no, or an ancient Scottish one for that matter? Well, I have used most but not all of them, but my telling is saying to others, 'experiment and try and find out more for yourself ', and this is what I encourage others with. Of course, picking up any plane of any type takes much adjustment to manage the nuances of them. I have done this over my half century working daily with wood and picking up tools along the way. Consolidat that into days and weeks and my experiments might number a many months and even years..I'm into nuts-and-bolts answers right here at the bench in the vise and on the wood. My time passing on my knowledge disallows distractions that, although perhaps interesting to some level, offer little value to teaching and training, making and experiencing wood working and working wood!

Comments ()