Paul's Plane Strategy

"Lay the plane on its side, lad," he said, the teacher.

"Yes, sir!" the boy replied. And he lay the plane down on its side unquestioningly.

I thought even then, aged 13, that it seemed a funny thing to do. I asked the teacher, "Sir, why do we lay it on its side?

"It protects the blade. Keeps it safe." The teacher said, in a way that made me feel stupid for asking the obvious.

I waited a minute, not seeing the obvious, and then said, "How does it do that, sir?"

The teacher stared at me as if searching my mind for an answer. "Isn't it obvious, boy? Think about it."

So I thought and I thought but nothing seemed obvious to my 13-year-old mind at all. I said, "I can't think of anything that protects the plane any differently than standing it up, sir!"

"Don't be impertinent, Sellers!" came back the reply. "Just do as you are told!"

And so it was for decades before that, even on a global level, woodworkers at an amateur level and a professional one unquestioningly laid and lay their planes on their sides with no good reason beyond, "Because I said!". Then, when I laid my plane on its side as an apprentice for the first time of using it, George said to me, "What are you doing? and I never did it again. It was just plane silly.

And so it can be with tradition. But we all start out that way and we have all been influenced by woodwork teachers in schools to lay our planes on their sides to protect the cutting iron when in reality it is a ritualistic procedure that has nothing to do with the protection of the plane iron in our day to day. I have had woodworkers agree with me that it indeed makes no sense even to them but that they will continue to do so regardless. This, to me, is weird. Not only is it a weirdly strange thing to do, but it's also just about the most inconveniently awkward thing in the world of working wood to do too. My planes come into play minute by minute. I switch between a heavy-cut, converted #78 scrub plane to a medium-cut #4 smoother converted to a scrub plane, a #4 1/2 jack plane, a #4 jack plane and a #4 smoothing plane all the day long. Imagine all those planes lounging around on their sides on my benchtop as I plane up my rough-sawn cherry and oak to superior levels of conditioning to make my furniture. Such is the way that I work today. It can confuse my audience but by doing what I do I am training them to not give in to the status quo set by school teachers preventing 13-year-old boys from plonking their planes down on other metal tools back in the 1930s. We who are at our own benches in our own shops with our own tools know exactly how and where we place our planes to work with them. My system for truing up wood is the best system for hand toolists to adopt bar none. It's not anything more than a practical solution to working efficiently and effectively without relying on machinery to get me where I need to be. Following is the system I use on every single stick and stem of wood that comes into my workshop and then into my videos as I teach and work.

The board comes into my work area and I usually cut it to length, adding an inch to allow for trimming and squaring; less if things are a little tight. I true up one edge but don't spend too much time on it just yet as I will work everything down further as `I progress. I will most likely use my #4 converted into a scrub plane for this edge-jointing but remember I am not fully truing just yet. With this edge fairly close I then rip the piece to close width so that truing up the wider flat face requires no excess of energy. Back to the vise or the benchtop, I use one of my two scrub planes to remove the surface fibres down to solid wood. My choice of plane depends on the condition of my wood. Heavy undulation from bandsaw cutting, twist, cup and bow, determine that I reach for my heavy-scrub plane which is my converted #78. This tool works so amazingly well for this element of truing and no other plane comes close. I may not have invented the scrub plane, I did invent the conversion of the #78 into a scrub as a strategy as key to the most efficient removal of flawed wood to lower the resistance for my other planing refinement.

My next plane is my lesser scrub, the Stanley #4. By now you will see that I am not in any way a proponent of minimalism in hand tools. That's plane silliness, but sometimes acceptably necessary by those with limited space and limited finances starting out. Little more than that. This plane has a shallower sweep to the cutting edge of the cutting iron and takes off the more regular highs left by the #78. Keep it good and sharp by learning the figure-of-eight method of sharpening curved cutting irons and gouges. If you ever want a vintage look to your tabletops, this plane can be used to that end. As the #78 has removed 95% of the serious faults like twist, cup and bow, and, indeed, I used winding sticks even at that coarser level to get closer, the #4 refines this all the further to get as close as possible to a trued-up first face.

My next plane choice is a matter of preference but usually, I will reach for a #5 1/2 because that extra 3/8" width in the cutting iron gives me that added truing capacity `I like in terms of width. The downside, of course, is the extra weight, surface friction and energy the extra width requires to motor through with the planing strokes. Initially, of course, it takes only minimal effort because the scrub planes leave an undulated surface and the wide and long plane rides the highs at first and the strokes are indeed ever-widening as the peaks are lowered down to the lowest of the valleys. I will switch then to the #5 on a fine setting to true up further after my #5 1/2 and of course, through every planing level I rely constantly on my winding sticks to make any corrective swipes to maintain striving for perfection.

By this point my wood feels glass smooth. Still, I am not quite done. I now use my smoothing plane for what it does exceptionally well which is, well, smoothing. This little Arabian stallion of planes twists and turns to engage any and all difficult grain changes of direction. I can spin it on its axis to keep always with the grain and after this, my first face is totally trued to dead flat.

. . . it's my #4 that gives me the finest refinement of surface of all. I keep this plane immaculately sharp all the time so that there is no conflict on the finished surfaces.

At this point, I will revert back to the first edge that I rough-trued with the #4 scrub plane and true it with a jack plane. Either one of the two will work fine. I could also use the #4 smoothing plane but the longer plane is helpful for straightening humps and hollows. Usually, I will go for the wider plane. The extra width gives me the same advantage as the tightrope walker with the long pole helping to balance. It's marginal but it is there. I use the square, registered against the first face, to check for squareness and sight along the corner for straightness.

With these two faces straight and true, I rip to width following either a gauge line if using a handsaw or the fence if using the bandsaw. I leave on a mere 1/32" (1mm) to plane down to parallel smoothness, which takes but a few strokes no matter the wood type. I may or may not need the #4 scrub plane first depending on the level of cut I get from the sawing. With a light setting on the cutting depth, the band width may be as little as 3/4" so it takes down both handsaw and bandsaw marks rapidly. I reach for my # 4 1/2 to swipe stripes across the width and edge and then my #5 followed by my #4.

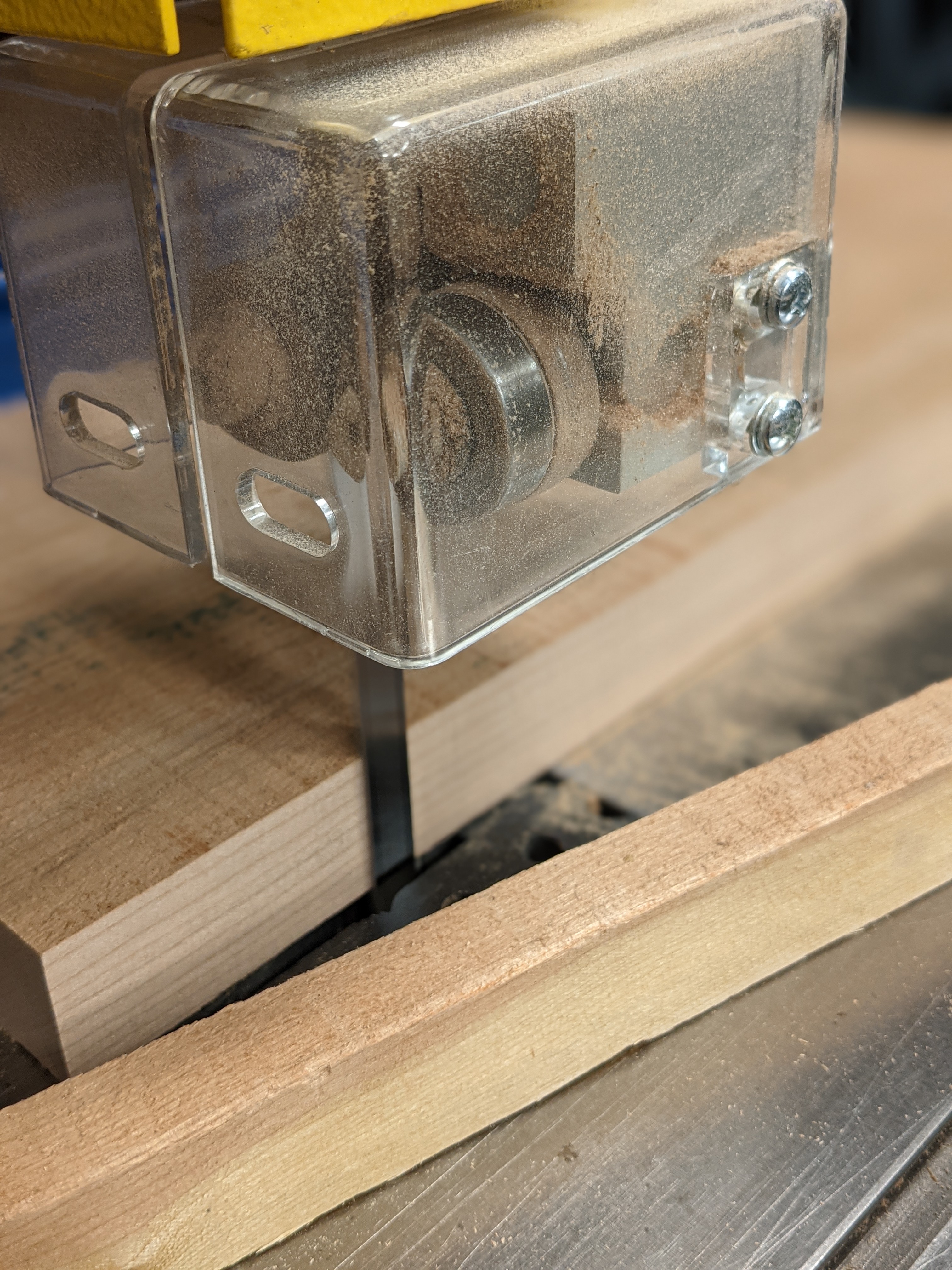

The contrast between my scrub plane irons is quite extreme as you can see here.

You might now see how silly it is to lay a plane on its side when the interplay in real life as a maker means the most efficient placement of the planes to switch from one to another throughout a process like this. My planes must be ready for action as must any woodworker who is time-strapped.

Comments ()