On Routing Out

Some months back, maybe a year or so now, I became troubled to the point that I felt awkward. Something had slowly but gradually happened and not by any particular intent. I take it on the chin because I think it was mostly caused by something very innocent that I did. Some are now calling it the 'Paul Sellers effect'. Ten years ago, I hardly saw anyone anywhere using a router plane. At that time I think many had abandoned hand router planes and had accepted power routers and jig making for cutting their dadoes, or then again a dado cutter set or head that fitted into the tablesaw.

When I started teaching online and in my hands-on classes I introduced students to the hand router but not just for dadoes but for truing up the faces of tenons and such. Online, I introduced a full system for creating perfect tenons that fit perfect mortises too. No one had done such a thing and it meant anyone could make perfect doors, tables, chairs and much more by using a router plane and my mortise guide system. Though today this seems to be taken for granted, what happened was that router planes, which were already a more scarce plane, gradually went up and up in price and even the premium makers benefited from my work though I never had anything to do with them nor took any benefit from them. The secondhand router planes like the Stanley and Record #71 sell for as much and often more than the premium maker new ones weighing in at upwards of £150 whereas a decade ago they were a mere £10 on eBay.

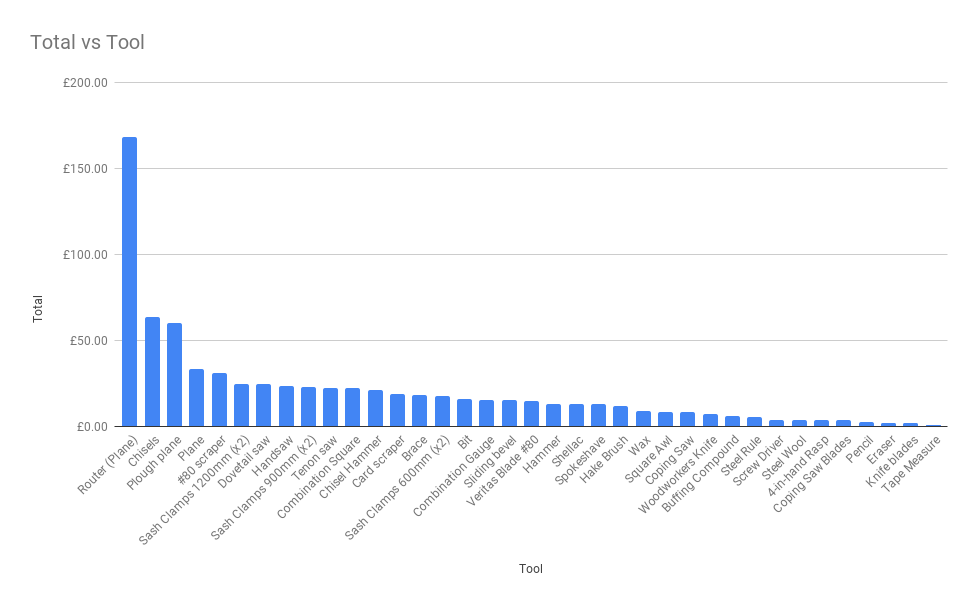

I think you will understand my dilemma. Here I was, for years now, telling new woodworkers and those new to hand tool methods that this is an essential tool; one as essential as any plane, chisel or saw, yet the tool would cost them as much almost as all the other tools put together. A temporary fix early on was my poor-man's router plane which comprised a simple piece of wood bored through to receive a chisel protruding through the opposite side. A great starter for any new maker, but lacking the ideal control necessary for finer quality work.

My concern was about something I felt responsible for yet didn't have an answer for at that time! Another plane, one I have collected for their unusuality, is the Edward Preston and the Tyzack-type router plane with its rectangular platten. This too skyrocketed in price mostly because I use one and have written about them but not because they work any better than a Stanley #71-pattern router plane. Currently, I just looked, they are offered as an eBay Buy-it-Now at around £700 and go up to £1900. They are an unusual option but they do not work any better than their Stanley and Record cousins. Of course, there are always new planes too, both the Lie-Nielsen and Lee Valley Veritas versions of the router planes are solid options and they sell here in the UK for around £165 (when they are available to buy).

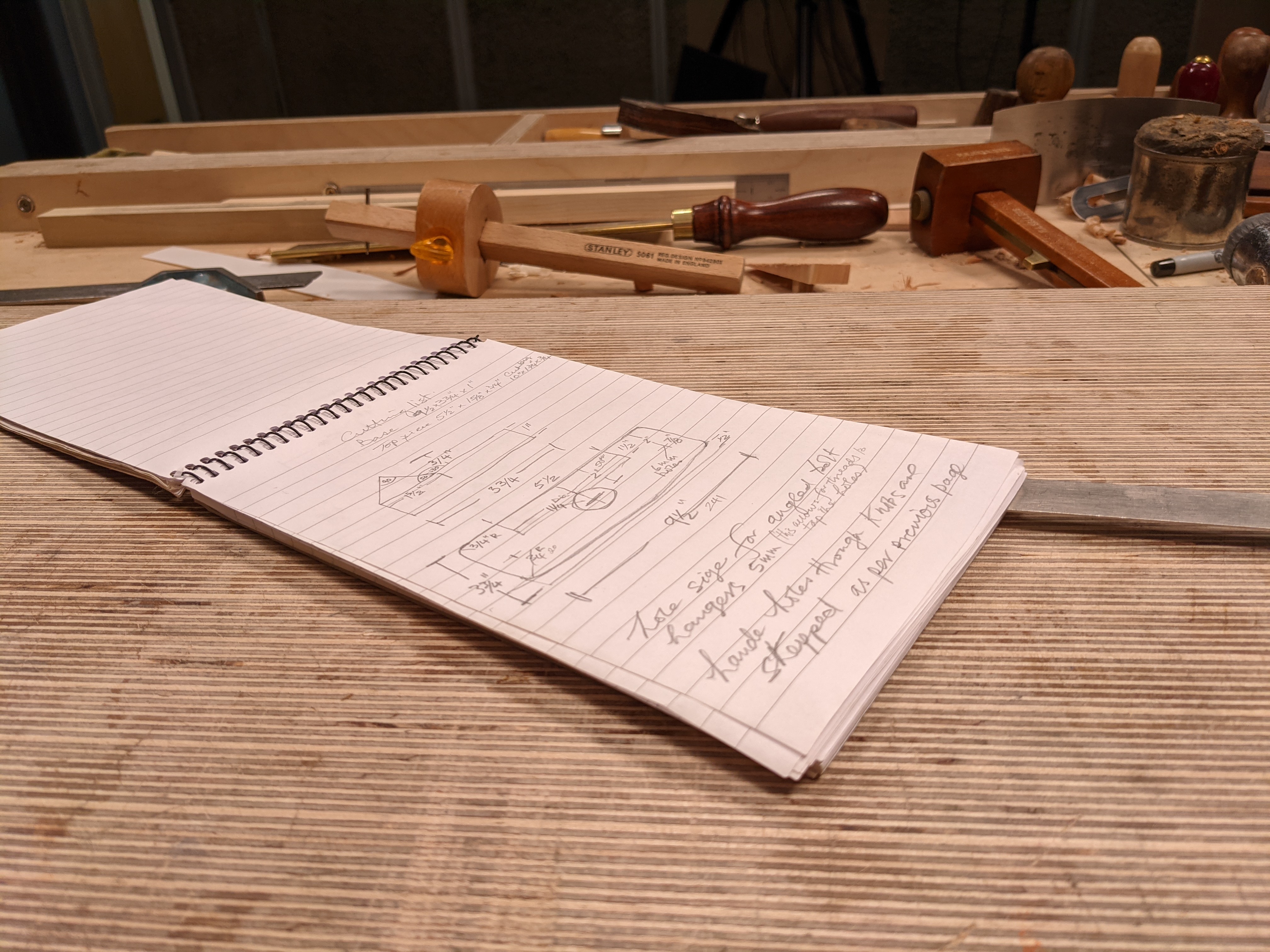

A little while back I sat down with my notepad and sketched out my possible options to help resolve a situation I found intolerable. You see, I have always sought answers for those who were looking for hand-tool methods of woodworking together with skilled methods and techniques of working. These were the people who were not looking for an industrial process but an industrious way of working with their hands. `They didn't want to substitute for skill by using machine-only methods. They wanted to master skill.

My first example of my idea came in the form of a cut down piece of wall stud -- a 10" length of two-by-four spruce if you will. At first it was a thread with filed nuts, wood screws and such; crude but working. Searches revealed the availability of a variety of components and with a blowtorch, a hacksaw and some O1 steel I came up with a cutting iron that worked great. I have come up with a wooden bodied router plane that has metal adjusters made from off-the-shelf components. It relies on sourcing a few components and making a wooden body and two metal components (a retainer bar and blade). I believe most woodworkers will be able to get the parts and build this for themselves. Since then, I have abandoned all of my metal router planes to use my wooden versions for everything. Why? Well, for some good reasons. I don't know about you, but I found that the vertical shoe-type cutters always manage to vibrate loose and that is the same with all versions no matter which. I have also found that the linkage between the adjusters and the cutting edge can cause the blade to move both up and down in some measure. That's not the case with my new router. What you set at remains firm and rock-solid all the way through at the setting you set -- what you set is what you get. It is mainly to do with the wood-to-wood negotiation of the plane. Wood absorbs and dampens the vibration and rigors of routing, whereas metal seems always to loosen what should remain firm.

I am going to make a bold claim here. I have never used a better router plane than the one I am introducing to the woodworking world. It is one you can build yourself using inexpensive components. There is no compromise in quality or usability. You can make several and have interchangeable parts to cater to different needs should you so wish; that's what I have done. We needed a direct answer to the problem of the price of router planes and we now have that because even a novice woodworker can make and use their very own with a small amount of time and effort sourcing the components and then perhaps a day's work to make the plane itself.

Tomorrow we will be releasing part one of two about how to make the plane but I wanted to write this beforehand to explain the problem being solved here. I think you are going to love this. Stay tuned!

Comments ()