It's worth stating

Some things are worth looking at more closely and some phraseology made by those making and selling can be a little more surreptitiously misleading than we think. Unfortunately, it's the selling that often tilts the truth in favor of the sale rather than our benefit, it makes all the difference, but I understand the reasoning. By selling I mean getting some additional benefit from something you say and do that ultimately results in a sale somewhere along the chain, but things can be added or omitted that lead buyers to believe something that is not so. We see it now with our planes all the more. How many features are espoused to give better results to hand plane work that prevent certain effects to our working them when much of the problem is that we don't understand exactly what sharpness is, or that we lacked confidence in taking that critical stroke or misread grain that would cause issues and should never have taken the stroke with a plane in the first place?

I have mentioned in the past that many sellers and makers of tools will say something that leads people to believe something is the cause of something when it's really not, or that something benefits you when it really doesn't, or that it's nothing to do with your lack of skill when that's exactly what it is, or that you don't need certain skills when you do. I remember when it said on disposable knife blades for utility knives that they should not be sharpened -- you know, "DO NOT SHARPEN!" and, "DANGEROUS TO SHARPEN!" There was nothing dangerous about the practice at all and everyone I ever knew and learned from at work resharpened their utility knife blades until they were almost down to the nub because it was quicker and simpler to do that than to dismantle the knife, find the blades and install a new one. Most people can go a year on a blade or more by just mastering a sharpening technique. Then there is the one about thin blades in pull stroke saws developing a thinner kerf than a traditional western saw. When in most cases the saw kerf, when someone takes time to actually measure it is actually even bigger. Most of the time it is more about underdeveloped skills than anything. I own and use many saws and still reach for push strokes because in my view they allow me a different kind of power and one that I enjoy very much. This is why, in most of my sawing tasks using say a coping saw, I use it with the teeth going away from me and never on the pull stroke. I use western saws and not pull strokes because 98% of pull stroke saws are disposable and you must keep going back to buy new blades, I just don't buy into throwaways of any kind because I like the art of sharpening saws to be part of my life long term and my first saws have been with me for over 56 years to date. Other disingenuous statements found on many premium plane maker blurbs surrounds the thick versus thin irons discussion and then too the hard steel alloys versus less hard steels for their cutting irons. I have covered this several times but in demystifying things it continues to rise up time and time again. Thin irons don't chatter in general working but for some the rare phenomenon may occur once every 15 years in the life of a full-time maker. Saying thick irons reduce the risk of chatter in the opening sentence of a plane promotion suggests that this happens all the time with thin irons when it's simply a lie. The surface washboard effect from planing wood is not chatter but skidding, where the plane balked at the plane stroke, your confidence was weakened and the plane faltered because of diffidence, nothing more. There are other reasons that a plane skips and jumps. Too many to list, but it's not usually because the cutting iron is thinner at all. If it were for that reason, surely the hundreds of thousands of users of Stanley and Record planes as professional woodworkers of different kinds would have said this is a problem. No, it came from the installation of a thicker iron in a modern maker's plane. The make had to diss one to sell what he made. By simply saying, 'Our thicker cutting irons stop the chatter associated with thin irons.' they created an answer to a problem that didn't exist and that had nothing to do with the issue at all.

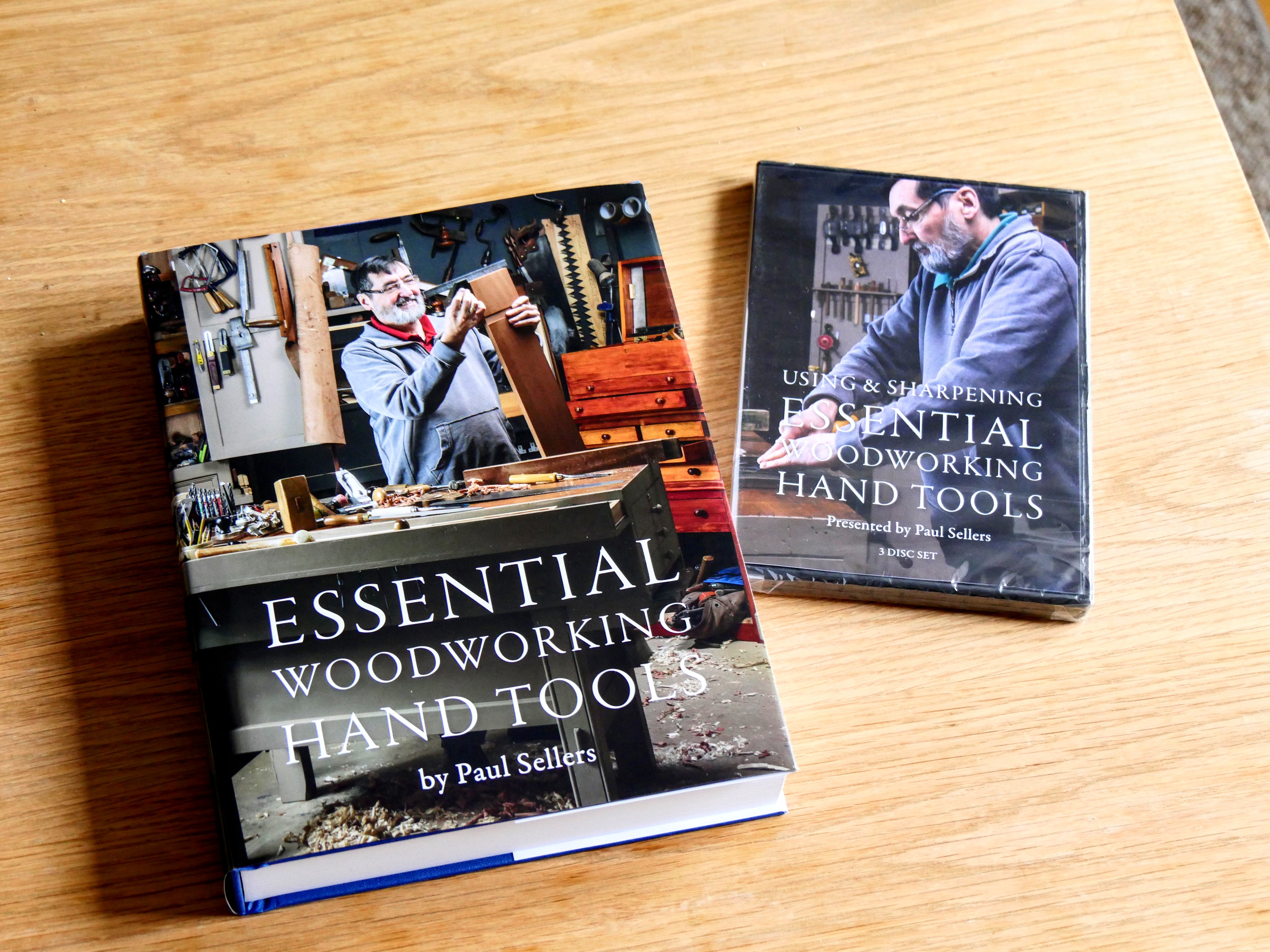

By sawing off the side of my Stanely plane I could see what was happening at the business end of my plane iron assembly in relation to the frog, the sole of the plane and the seating of all the components. As far as I know, I was the first to ever do this and make it so public in my book, Essential Woodworking Hand Tools. `I did so because of the need to know what was truly happening right there at the cutting edge. Ultimately, it made me realise why crafting artisans between 1867 and 1980 did not buy into the Bed Rock planedesign produced at that time and why Stanley could not sell their Bed Rocks no matter how hard they tried. These men would not change because they could not justify the price difference but more likely than that, they could not see why they should change at all because the two plane type achieved the same outcome identically but the Bed Rock was heavier and less nimble. The thickening of the cutting irons came in gradually at the start of the 1980s and some might compare this with the thicker irons of old but the thicker irons of old were not the same and did not have parallel irons but tapered versions that went from thick to thin to counter the forces of planing and cutting iron assemblies being wedged in place rather than held by a mechanism. The taper caused the iron to tighten under the excesses of pressure and so prevent the back-slip that would occur with parallel irons.

Someone recently questioned my theory of the cutting iron being capably flexed by the lever cap where both cap iron and cutting iron bend to conform under the direct and indirect pressures of the lever of the lever cap in the Bailey- and Bed Rock-pattern series of bench planes. The commenter stated that this would not be possible with the thicker irons of modern planes, whereas there is truth to that, that's not what was intended in my saying the iron flexed thus but simply to say there is no real reason for flattening irons made and intended for this series of planes. I think that there was nothing wrong with his assumption and it was good that he expressed his thinking because we should all question the authority of those who speak. It made me question my own authoritative voice and so I took it the step further and experimented all the more to make certain that what I said was so, even with the overly thick irons. To help defend my position, I installed two cutting irons (because no other iron would fit without me changing some of the dynamics unnecesarily) and showed how the lever cap was more than capable of conforming the most twisted of cutting irons to lay flat to the frog without any excessive force being needed. The reason I wanted to show this? Because too many are saying that the whole of the large flat face of the cutting iron 'MUST'' always be flattened within a thousandth of an inch when in reality it can be twisted and left twisted without any issues. Of course, two irons of 3.6mm total thickness is not the same as a single thickness of 3.6mm, but it helps to show that added resistance still allows the flex I speak of.

Re the thicker irons. I do know of one of the most serious modern plane makers who told me that they had their first cutting irons made for them and never specified the thickness that established their cutting iron thicknessess at well over 4mm thick. He told me that they had left ther order with the subcontractor many years ago and the plate was simply what the maker "had in stock at the time" and they had stuck with it because it worked. Not too scientific but most likely what we all might do in the same circumstances. "Why fix what ain't broke?"

I am not saying that there is no place for thicker irons. I think that there is, just not in every plane and especially not for the main body of working planes, those that are the bevel-down versions we use for truing, squaring, leveling and smoothing hour on hour. Harder steels too do not offer enough extended work time to bother with and certainly thicker irons are a waste of space in bevel downs because the one thing that matters is good, quick sharpenability and efficiency. Also, it is worth noting that without the added tension created by using a cap iron, thicker blades are more than likely to be necessary to improve the cut because all planes in the UK for 250 years, even the thick, tapered irons I spoke of, had a cap iron to specifically increase tension in the steel cutting iron right down there at the cutting edge. It wasn't some whimsical addition, it was indeed a tensioner that no one anywhere ever discusses. Especially would this be so for the newer and larger bevel-up planes where a tensioning cap iron cannot be used. They had to go with the thick irons we have offered to us today. Are thick irons necessary for the Bailey pattern and Bed Rock planes then? I don't think so at all, and if there was some benefit I would say it is soon negated by the extra energy it takes to sharpen the wide band of steel that forms the cutting edge of the bevel on thicker irons. Mostly, it's a matter for personal choice. The problem is of course that m,ost new woodworkers do not know which way to go so they go off what the sales pitch gives them which always top buy a thick iron replacement. I have yet to meet a salesman that was a woodworker first and a salesman second. It doesn't happen, though most will claim some connection to a great uncle being a woodworker and it being in their genes. I most certainly would not ditch a thin iron to replace it with one costing more than the plane `I bought thinking it's some kind of silver bullet that takes care of something that doesn't exist -- like "chatter!" Aargh! Here is an example of a supplier selling a thicker iron to replace a standard one; "A thicker blade will tighten the mouth opening and reduce chattering." The tool in question actually never chattered in its life -- not because of the size of the mouth opening and neither because of the thickness of the plate. But now, globally, this source of misinformation is out there and new woodworkers would find it extremely difficult and highly confusing to disseminate the untruth of it.

Most of the time I might shout out what George shouted out to me as a 15-year-old apprentice in 1965! "Sharpen up laddie! Sharpen up!" 99% of faulty planing is caused by a dull irons and friction on the sole of the plane in connecting to the wood. Nervous anxiety, lack of confidence, lack of experience all play their part, but there is a good reason that until it was introduced no crafting artisan replaced what they had with a thicker iron or even the idea of it. No, they knew what the issues were and it was not the thickness of the iron. Have patience, sharpen more than you think is necessary, persevere and you will find your plane works perfectly well after few hours in the saddle. There is no need for thick irons and no need to open the throat of your plane by filing it to take a thicker iron.

Comments ()