Prepping Wood III

I have never really gone back and forth on my methods for prepping stock from rougher slabs, planks and boards without relying on the use of too many machines. I am happy with the evolutionary processes and shifts to date that add tactics to enhance my work and at the same time make my hand methods less tedious. Dispatching the old machines to the scrap dealer was a great move for me but I recognise that producing stock on a large scale is likely the only way for business woodworkers to go. The issue for me comes when business woodworkers abandon all handwork and then diss hand methods without ever having tried hand methods. I met a serious furniture maker who went through 24 hours of self stressing at the thought that the only way he could install a recessed hinge in a particular case would be by hand. He applied to what was quick and simple hand method what he did to his power router and applied stops along cut lines to prevent any possibility of an overcut with his chisel work. This increased a two-minute section of work to half an hour and then his stops shunted and moved the line anyway. Oh well!

When I had the different woodworking schools in the US and the UK it would not have worked for me to hand-cut 500 pieces per class of 20. This donkey work is for the machine for a variety of reasons and of course, for some non-business makers, the machine can be a gap-bridger that is essential to them. The one woodworking machine I rely on nowadays is my 16" bandsaw, which suits me very well for taking any rough-sawn stock down to lesser sizes I can get by resawing heavier sizes.

My stock prep tools comprise a pair of winding sticks to guide me when taking the initial misshapes from off the first large face, a #78 rebate or filletster plane with a shaped cutting iron to use as an aggressive scrub plane, a converted #4 bench smoothing plane with a curved iron and other adaptations to use as a second level scrub plane, a #4 smoothing plane for truing and fine finishing and a #5 jack plane for leveling and smoothing. I do also use two less essential planes, a #4 1/2 and #5 1/2 for edge work truing and edge jointing as well as face work. With this cluster of planes I can rapidly reduce stock to accurate levels and prepare all of my wood for joinery and other aspects of work.

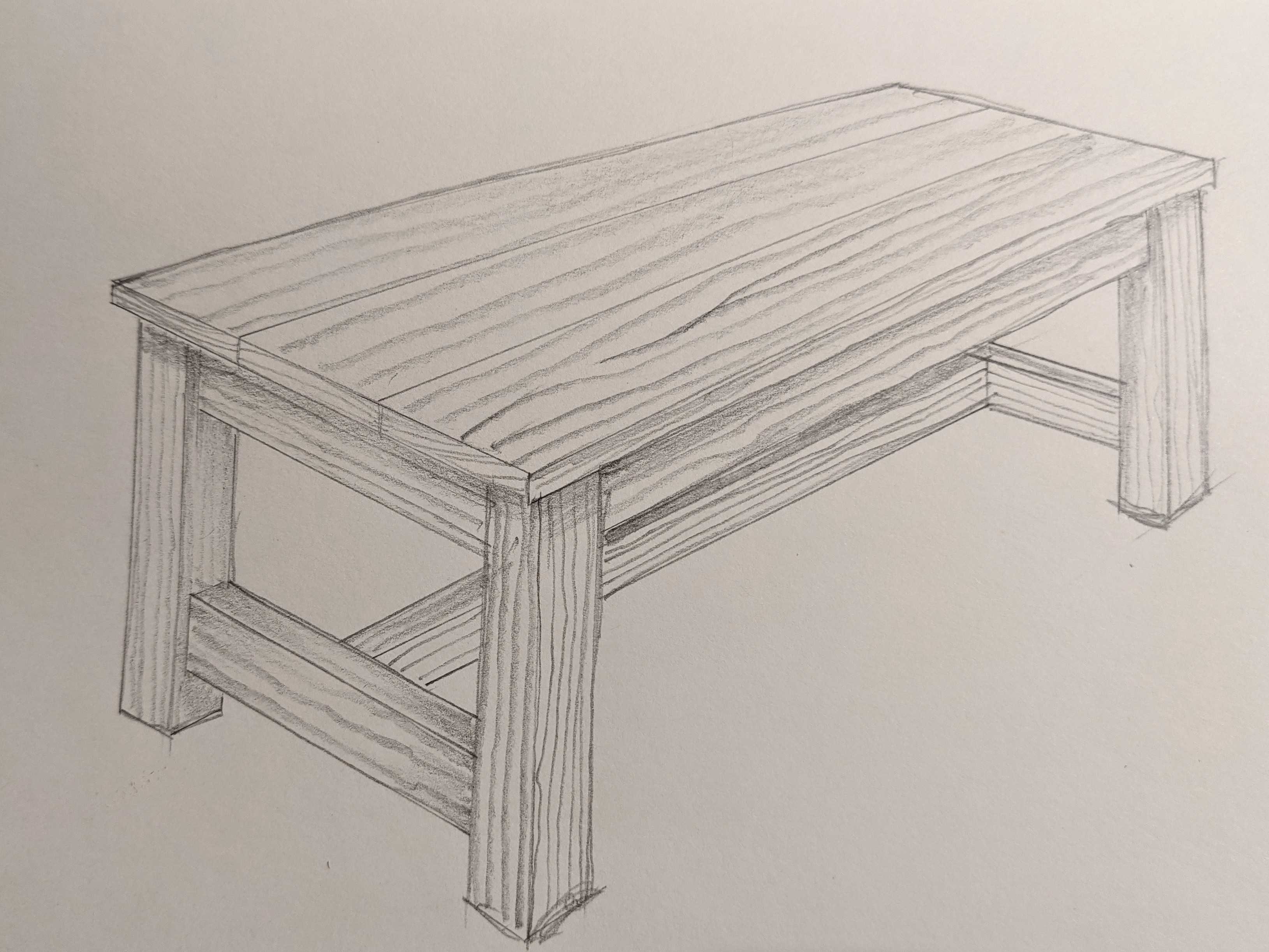

In most cases, it is always best to reduce your sawn or rough-cut wood closer to the length, and width you will need for the parts in your project. I will make this concrete for you first. Imagine a table with 3" square legs, four aprons and a tabletop. This table also has a stretcher and two lower rails; the stretcher unites along the long axis of the table as shown in my sketch. The final, overall height will be 30", length, 72" and depth across, 42". The final sizes of the components are:

Tabletop 1 @ 72" x 42" x 7/8"

Legs 4 @ 29 1/8" by 3" x 3"

Apron long 2 @ 69" x 31/2" x 7/8"

Apron short 2 @ 37" x 3 1/2" x 7/8"

Bottom rail 2 @ 37" x 2 1/2" by 1 1/2"

Stretcher 1 @ 69" x 2 1/2 x 1 1/2"

The best method for attaining wood is to go to your chosen supplier and pick out your own wood. Call ahead to see what stock they have available, you could save yourself a trip if they're out. 3" square stock for the legs may not be their stock size and they may need to order it in for you. They may have had a run on the particular wood you want, so it is good to let them know that you are on your way anyway, and when they know you, they may hold something for you for an hour or two.

Visiting a timber/lumber yard is a good way to let them know who you are and it is always good to give a little of your time without taking too much of theirs to get acquainted both ways. At the supplier, you can browse the stocks and the odd-ends bins for shorts. You might well find some special pieces in small sizes there too. I bought some thinner, 5/5" to 3/4" quarter-sawn oak which had some small wormholes in some isolated parts but not throughout.

This type of stock is handy for a variety of small projects and it's good to take advantage of a trip you might not otherwise take. In all of the yards that I have established a relationship with they have always let me pick through the racks and stacks to find what I want. The critical thing here is respect. Don't treat small companies like the big box stores and leave wood you rejected in a heap or miss-stacked. Even when the wood has been poorly left, I will restack wood correctly if I have picked my wood from the same misplaced stacks.

Once you've glanced around and perhaps let your friends at the mill know you are there, the search for wood begins. There is no short cut, each board must be touched, flipped and eyed for any obvious evidence of why not to buy this or that one. You are looking for wood with the minimal amount of defects such as deep cupping and twisted stock with long curves, too many knots and surface checking (fissures) along the length mid-board etc. Cracks known as shakes in the UK and checking in the US can travel into the length of wood beyond what is visible. Unless you know that you can cut either side of the splitting, I suggest you leave them there. Watch for sapwood, damage on edges from the forklift, indents from skid strapping, severe sticker stain that sometimes ruins a good section of wood because its gone too deep below the surface.

Wood at the yard can be stored in racks laid down and stacked or stood on end. Stood on end is easier to choose through and because the boards are allowed to 'float' and not under compression from stacking will usually show distortion straight off. One defect I do try to avoid is twist and by this, I really mean twist that seems more excessive than normal. Most boards will have some level of twist, the goal is to pick boards with as little twist as possible. By the time you have gone from one end of a board to the other to plane the twist out from both sides and then make the two faces parallel you can lose 30% of the thickness and what you hoped would be 3/4" (19mm) might well not make 1/2" (13mm) and this can be worse if other defects like cupping are present. Stacked racks are more economical on space and stacking does keep boards flatter if your supplier has a large quantity. From this stock, you must basically pull the wood and eye it from the end to look first for twist and then bowing. Pull the board until you can see the opposite end, hold your end up to eye level and sight your end with the opposite end. You will soon be able to detect even a minor twist in say an 8-10 foot length. If you have your end level to your eyes, the opposite end will show a high point when comparing the far end with your end. You might think about taking two parallel 1" by 2" sticks, 16" long with you if seeing twist is a challenge for you. We call these winding sticks and they will obviate twist more readily because they stand clearly above the wood's surface and are wider than the boards you might buy. Place one on the far end and one at your end and then sight from one to the other to see if twist levels are acceptable or not. It is unlikely that the boards will have zero twist. The greater the discrepancy twixt the two, the greater the loss of wood in the reconciliation.

When a board curves along its length, usually from end to end, we call this a bow. When we rely on a long section say 7 feet long to be straight and our board or section is 8 feet long, with even just a 1/4" of hollow, straightening the board by planing one side true is not the end of the work. We remove material from each end along a straight line and lose that 1/4" of an inch. Then we must plane the opposite face to remove the bulged area of the midsection by the same 1/4". So now we have lost half an inch from our mass. But this may not be the end of the task. Removing wood can release more stress and the board can bow a little yet again. In such a case we need to go back in and repeat the process even though it will usually be on a lesser scale. This all factors into the reality that from a 1 1/16" thick (one inch) board we often only end up with 3/4" - a nominal thickness in other words. This does not necessarily mean that we will automatically dismiss an otherwise beautifully-grained board. We may well be able to cut the board to much shorter lengths for our short table aprons for instance. A half-inch curve along an 8-foot length when cut into four for any needed shorter sections will result in a barely discernable curve that can be planed out with just a few strokes. We could also still plane the outer surfaces of the longer length needed without removing the bow but still out of twist and parallel for the long aprons. By judicious placement, we can put the curved length so that the crown is innermost and push the aprons out with our turn buttons when the undercarriage of legs and aprons is completed.

There are subtle differences between the terms splits, checks and shakes. I don't recall in living and working in the US for 23 years ever hearing the Americans use the same terms we use here in the UK. I just heard the term 'checks'. Something I never heard in the UK. Checking seemed to be a catchall for any of the various splits we encounter. In the UK we have three types of notable shakes or checks. We have the heart shake, the star shake and the cup shake. These developments are specific. A heart shake emanates from the centre of the log along the medullary rays which also emanate from the centre in the same way wheel spokes go from a central hub to the outer wheel rim of a bike wheel. When we see that medullary rays radiate as cellular structures reaching out from the centre of the log we also see that they are perpendicular to the growth rings and that these cell structures can separate to form a star-like configuration. In planking our boards, these cells sometimes separate resulting in what appears to be cracks. In some cases these separations can be parted and glued permanently back together. The hearty shake generally has only two or three points coming from medulla or pith, the epicentre of first growth, dead centre in the section of a tree stem.

A star shake also emanates from the dead centre of the tree but the splits are more numerous. This splitting is caused by differing rates of shrinkage after the tree is felled. If left to its own, the tree will continue to dry 'in the round' so to speak. Because the main stem is still enveloped by its outer 'skin', the outer layers of bark, cambium and sapwood, the main body of wood retains a high level of moisture similar to the levels in the growing tree. Left to its own, a tree will gradually rot and degrade back to the earth. To prevent this and to lower the risk of splits and shakes, we slab the tree into boards so that the moisture is released equally from both sides of the slabs. This is done as soon as possible after the stem is delimbed and separated from its roots. In most cases, where the wood is wanted as a harvested material, the ends of the logs are painted or waxed to slow down the release of moisture from this area of the stem and this reduces the degree of splitting that takes place.

Cup shakes are also called wind checks in the USA. I have seen this occur greatly in mesquite tree stems where the wind checks become very evident as long-grain separations along the whole length of the stem. Cup shakes occur along the growth rings. This defective growth takes place on the medullary rays where the rays fail to bind together in the annular or growth rings in a consistent way.

Crooks and crotches in a tree growth can be both good and bad. Crotch grain is the most highly figured of all and can give us some very decorative material for book-matching and so on. This section of a tree results in swirling, non-continuous grain patterns and omni-directional swirls that contrast markedly with the regular straight-grained sections we generally rely on in our construction.

Burrs and burls are one and the same and the US uses burls more than burrs to describe this outward bulge on the side of a tree. Elm is particularly noteworthy of a tree with burl wood and this outer growth roots itself as non-productive buds within the stem of the tree. This rocking chair by John Winter is a prime example. With judicious matching, some veneering, an outstanding architectural construction can be enhanced still further using 'different' wood.

How does all this affect us in the timber yard?

Well, what we see on the end grain of the log tells us about the inner growth and then what we see in our boards and planks helps us to understand what we are looking for and indeed, ultimately, what we are buying. As non-mass-makers, we engage more with our materials than commercial enterprises do. We have no guarantees and we want to analyse our stock asap when we arrive at the suppliers. This way, we minimise loss and of course waste of the valuable time we have no excesses of. This preemptive work is an imperative for us.

To be continued very soon...

Comments ()