A Note About Wood

There are some things that you need to know about wood. When the masses need mass-made to keep down costs there is always a price to pay. We lose massive sections of forests in a day or two and we plantation-grow studs for stick-frame building that never mature much beyond a stud-size section that is needed. There is little waste. The wood is force-dried in a kiln because we don't need to be concerned about distortion if it's constrained inside a frame forming a stud wall in a mobile home. For woodworking and furniture making it is a very different story. Take that stud and rip it down the length and stresses are relieved that then reshape the stud. A straight stud so treated will then look like a boat propellor or the planking for the side of the hull for the same boat. We must then rework what might have been straight to take out the newly formed distortion. This will result in much greater expense because we lose wood every time. This distortion is the case even if the wood is dried down to 5-7% because lowered moisture content does not mean less stress and can indeed mean much higher levels of stress within the fibres of the wood. You can only imagine the tonnage of green wood stacked in this kiln. You can see how force drying stacked wood in a kiln constrains the wood to a certain level of continuously restrained conformity. Under the weight of other wood, and with the heat of the treatment itself taking place, green wood readily conforms to the pressures exerted. Taking it out of the kiln and packing, stacking and banding it tight for delivery can make a bundle look pretty good. You arrive at your Home Depot and Home Build big box store, pick up the 30 nice straight studs you need and start ripping said wood and lo, look what happens!

It doesn't matter how much the wood was dried down to in the kiln process, what matters more is how it was dried and at what speed. Force drying, that is all kiln drying, speeds up the process to give us wood much sooner than if it was naturally dried by simple air stirring in between the layers and without introducing forced air and heat. Most of the wood we use these days will be kiln-dried. It is all about economics. It takes a fraction of the time it takes to passively dry our wood naturally by simply air-drying it. Using forced drying builds tension in the wood that occurs at a much lower level with air-drying. So what's the difference? Force drying never considers what we used to call seasoning. Seasoning doesn't actually take place with any force-drying method even though that term might still be used by mass wood processors and applied generally to all drying methods. Seasoning only happens when the log has been converted into stock sizes and the resulting wood is stickered (stacked level and with sticks of wood at regular intervals between every layer to fully support the wood and also allow air to pass freely between the layers) and air-dried. Seasoning allows the wood to move according to the gradual release of moisture. This is the reason that air-dried wood is more stable after the drying process than the kiln-dried type, but having said that, some certain wood species will always be more prone to distortion and when wood is sympathetically dried using a combination of air- and kiln-drying methods or even just kiln dried at a less forceful rate the wood will be less distressed by the process.

How to tell stress

Whereas there can and often are external signs of distress in and to wood that shows after drying, all too often there will be no outward signs at all. You must rely on the supplier to work with good processing mills for his supplies. Within the wood itself, when the wood is dried too fast, there can be something called case hardening and it is this that causes the greatest distortion to newly harvested, freshly dried wood. We don't truly see any of this until we cut into the wood. Inside, we can find separated cells and especially along the tangential rays of certain woods like oak where something called honey-combing takes place inside but is often not visible at all on the outer surfaces.

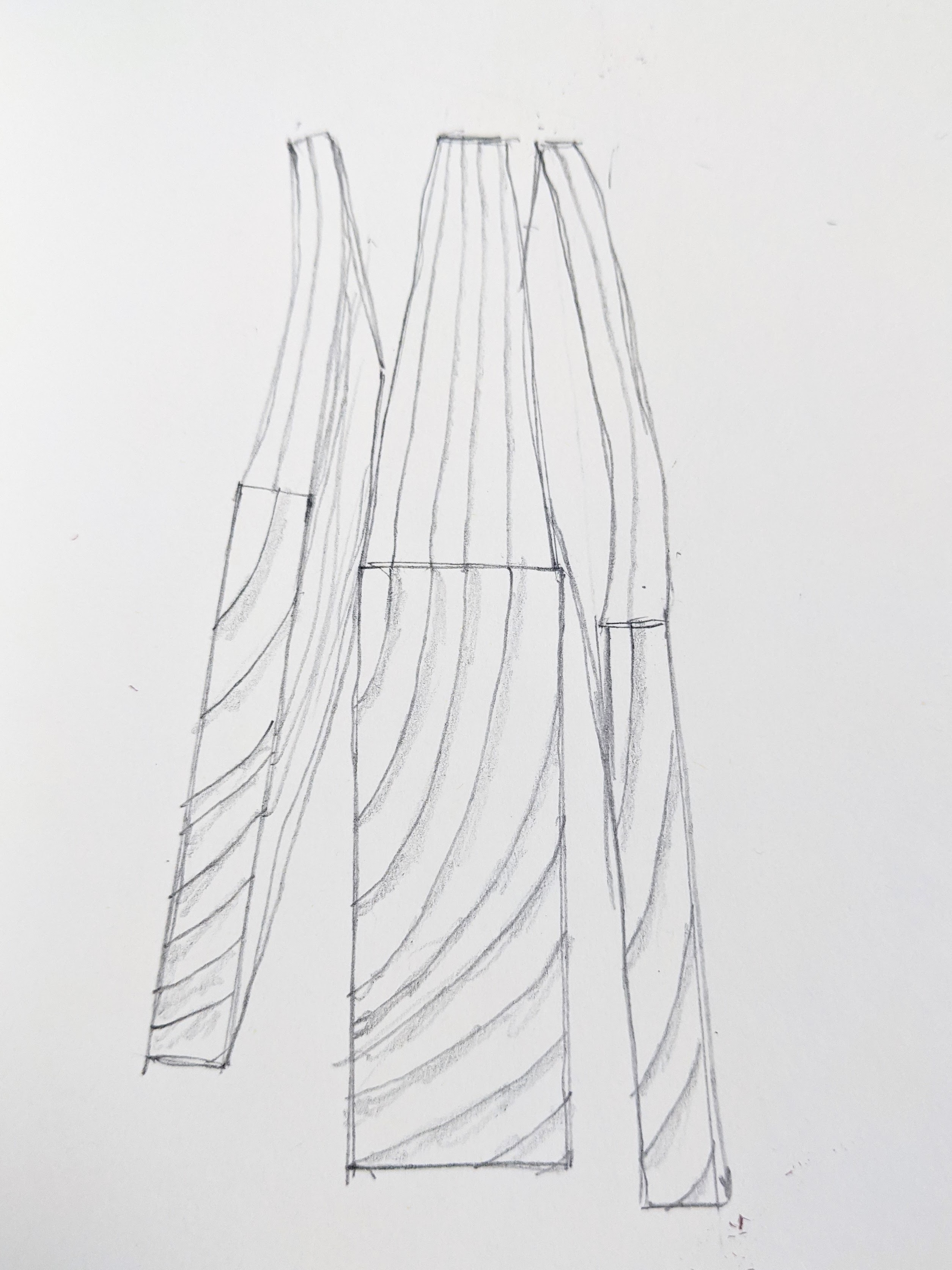

This picture below is a good example to see how the wood pulls away or curves in at the exit side of the blade. In this case, you will see that the wood to the outer left side is twisting as stress is relieved by the as-yet incomplete ripcut of the bandsaw. This relieving in a sense destresses the wood so although we see twist, cup and bow as distortions in the wood, they are the actual relaxed condition. In this case, we can see the twist taking place and also the bow forming, so by the time the piece is cut away, the remaining pieces will all have distorted to some degree.

Crosscutting wood too can show the condition of stress within the wood's fibres. In this picture, I simply took a narrow section off the end of a board with a painted end and the 8" wide board of 1" thick cherry opened up from the 1/16" saw kerf at one side to a 1/4" on the other.

Comments ()