Prepping Wood Part II

When we venture out on our woodworking adventure for the first time, when there is a seriousness ordering our steps, we at first make forays along paths well-trod. Going into the big box stores in search of tools, equipment and our raw material, wood, can be like entering the unknown. It can also be disappointing in that expectation does not match what we hope for in the opening experience. I liken this to getting out in nature by camping out but glamping in a yurt with all home comforts matching our home life instead. The experience was comfortable but more detached from what we sought. Eventually, you will discover trails over moors and through woodlands, crossing rivers and climbing higher in search of wood from a dozen sources and not the least of which is skips and someone else's waste disposal. Generally speaking, the huge stores are somewhat dull and boring compared to finding a small mill somewhere where the miller slabs, stacks and stickers his harvest ina kiln he dries down the wood with. They are not truly a great place to begin an adventure into woodworking.

The magic of starting any craft automatically carries with it the essential ingredient of enthusiasm that emotively results in action. The big-box store is often what we relate to most because they are so big, present and impressive. It's not because they are in any way experts, it's because it's they're the only thing we're likely to know of and have been exposed to over the recent decades. And it is not just the big box stores either. Going online these days you will see a pretty impressive array of 'other' apparent experts in the form of online woodworking suppliers. They can persuade you into believing that you need a £20,000 budget to get started in woodworking. What you actually need are some basics in the form of wood and tools alongside disposables like sandpaper and glue, nails, screws and such like that. These can be had for very little money if you take time to shop around. I've used eBay successfully many time too, especially for hand tools and other support equipment. So far I have found it competitive and generally reliable. I recently purchased a new-to-me Woden vise to replace my soon-to-be-pensioned off my vintage Woden # 3189B woodworking vise which after a hundred years of holding wood is beginning to show signs of wear. I say some of this because for the dimensioning and preparation of wood you must have a bench and a good vise.

My goal through the years has been to not tell you what you need but to show you. It's almost 30 years ago since I started entertaining the thought of teaching woodworking to others. Some students brought a case or two of their own tools. I skimped down and supplied no more than ten. The ones that took the ten and worked with them seemed to me to be the more successful. The pluralist illusion of more is better proved to be delusional. I coined the phrase and set up my first woodworking courses on this one statement: 'With ten hand tools and three joints you can make just about anything from wood'. I never changed it and 6,500woodworkers attended the courses based on this premise. These opening paragraphs are to clearly state that the big-box stores are not generally the place to go to buy wood, hand tools or a workbench, etc. Especially is this so if you are moving towards making good and fine furniture. The wood they sell is to be buried behind plasterboard (sheetrock USA), under OSB, inside walls and under floors, and then used to build outdoor decks too. The tools they sell are meant to hang from a tool belt and be pounded with a steel claw hammer. These carpenters, in general, have almost everything come from a chopsaw. They work off their knee and a mobile workstation or a sawhorse/trestle of some kind. All of that said, some will have special categories of finer or better wood, tools and related equipment. But I am really talking about the US here, not the UK. UK big-box stores are generally deplorable. Don't give up yet though. We'll get there!

Mostly, at the chain store suppliers, we will buy some softwood like pine or fir, spruce, and so on in our starting out. We might also look to secondhand wood and even pallet wood. We don't yet know if we will be 'any good' at woodworking. It stands to reason that when we think wood we think carpenter. In some countries this works, in the UK and the US, it does not. In some cultures, carpenter is a generic term inclusive of anyone that works with wood. Some cultures provide specialised classifications identifying the exclusivity so we have carpenters, joiners, coopers, cabinet makers and two dozen woodworking crafts besides. Being a woodworker is to be culturally generic - an unclassified group accepted by all other amateurs but not by those qualified by associations and bodies even though in my experience it is the amateur who has done the study and research to better understand more than one area of how to work wood. Anyway, we're not yet too sure what we are looking for or even looking at when we arrive and walk through the racks and shelves of wood and tools.

Depending on the store, we might find wood in good shape and dry, we might be lucky and hit a good amount of newly delivered stock fresh from the sawmill, but we also might find the picked-over leftovers with splits and banana shapes. But we are excited and what will do for us at this point will not be so when we have gained some working knowledge of wood. Whereas there is something exciting in the midst of our naivety, our newfound energy often results in our buying something resembling a boat propellor blade or the planks to form the vessel itself. Without advice, our insight as to what we are looking for or not looking for is limited. Choosing wood can be something of a dark art. Even now, I still get caught out by one thing that attracted me but that also, at the same time, blinded me. If we take just pine alone we can miss 20 different points to look for before we buy. Are the knots dead knots or live? Do we know such things even exist? What is the difference? Should we still buy such wood and how do we decide? Moving up a notch, is the wood dry or green? How was it dried? How has it been stored and in what conditions? Why is this board so dark and this one so light? Are they different species or all one? This piece is darker in the middle than on the outside. Why? How does pine work with hand tools? Why are the rings so different in depth of colour? Is all pine one species on its own or are there many types? Who will answer all of these questions for you? I would never rely on staff in 95% of big box stores. Most pine in B&Q, Jewsons or Home Base in the UK or Lowes and Home Depot in the US is listed as some kind of generic white wood, but white wood is not a species at all. It just looks white.

And then answer me this. Is softwood soft wood? Is pine soft wood or softwood? Confused? How about is hardwood hard wood? Is pine hard wood or hardwood? Did you know that this is mostly to do with how the tree grows rather than anything to do with denseness and hardness? Why do softwoods drip with resin from pockets in the wood itself? There you are, the 20 basic questions. I could give another 50! Oh, and my spell checker wants to change all the 'soft wood' words to 'softwood' and 'hard wood' words to 'hardwood'. Can you see the dilemma?

If what I have said does not confuse you, carry on - you're on your way to becoming a woodworker. Okay so far? It gets easier. Most woodworkers in the carpenter's trade of construction, work their wood only with power equipment. They like softwoods because it is easy on their so-called power tools and this makes it easier on their bodies too. For us hand toolists, we are bemused. Softwoods like Southern yellow pine, Eastern white pine and several others, work by hand tools beautifully. Redwood from northern Europe on the other hand works beautifully much of the time but at other times will surface tear whichever direction you plane it. Using power equipment like belt sanders, power planers, table saws and so on remove the excess wood by a million strokes and a million tiny bits. Hand tools don't. We hand tool users on the other hand take wide shavings off and try for long lengths from long strokes too. Such strokes minimise the need for abrading wood to conformity. The carpenter on the job site is least likely apt to give good or apt advice to anyone wanting to make things for the home. Most carpenters I ever met could no more make a door than fly to the moon. They buy doors from big box stores in frames prehung so that a half dozen nails fixes the frame in place and the door needs no remedial work. When I built my first house in Texas I made the doors by hand. The carpenters were gobsmacked with their jaws dropping on the floor. Last week I made my greenhouse door from5 two-by studs in a morning replete with the frame. By maybe 2 pm the door was hung and my greenhouse became functional. I used spruce because it was almost free and with paint on and good maintenance it should last me for a hundred years. Carpenters today are indeed a different breed than those of a hundred years ago. Perhaps to describe them as fitters might be more accurate.

Walking you through this post is my intent and attempt at goodwill. Here in the UK we use a term that may not have reached around the world but its this: "He's like the weather, he can't make his mind up!" I often think that wood too is like the weather and in many ways that is with good reason and good linkage. We think that wood should just make its mind up but instead it keeps expanding and contracting according to the weather year on year and season on season. Wood is affected greatly by the atmospheric moisture levels surrounding it whatever that level is. A solid pine door, even with well-made joinery and allowances for weather changes, can expand or shrink to such a degree that the door almost falls through the opening or sticks stubbornly and immovably within it. It can also do the same in a home depending on the family size, the air conditioning if any and of course things like time of year, the number of bathings we take and much more. Does it seem impossible to determine how dry your wood should be? Well, there is much guesswork to it. I have no proof of this except my own experience, but wood has greater 'elasticity' in the first few years as a furniture or woodworking piece. I see that eventually, increases and decreases in width through absorbing and releasing moisture from the wood fibres becomes lessened by age. In my space, I have noticed that it is just about always shrinkage that takes place and not expansion. Flush tenons always protrude ever so slightly - dovetails too. I actually like this though. I have no problem. Usually it's less than a paper thickness, no more.

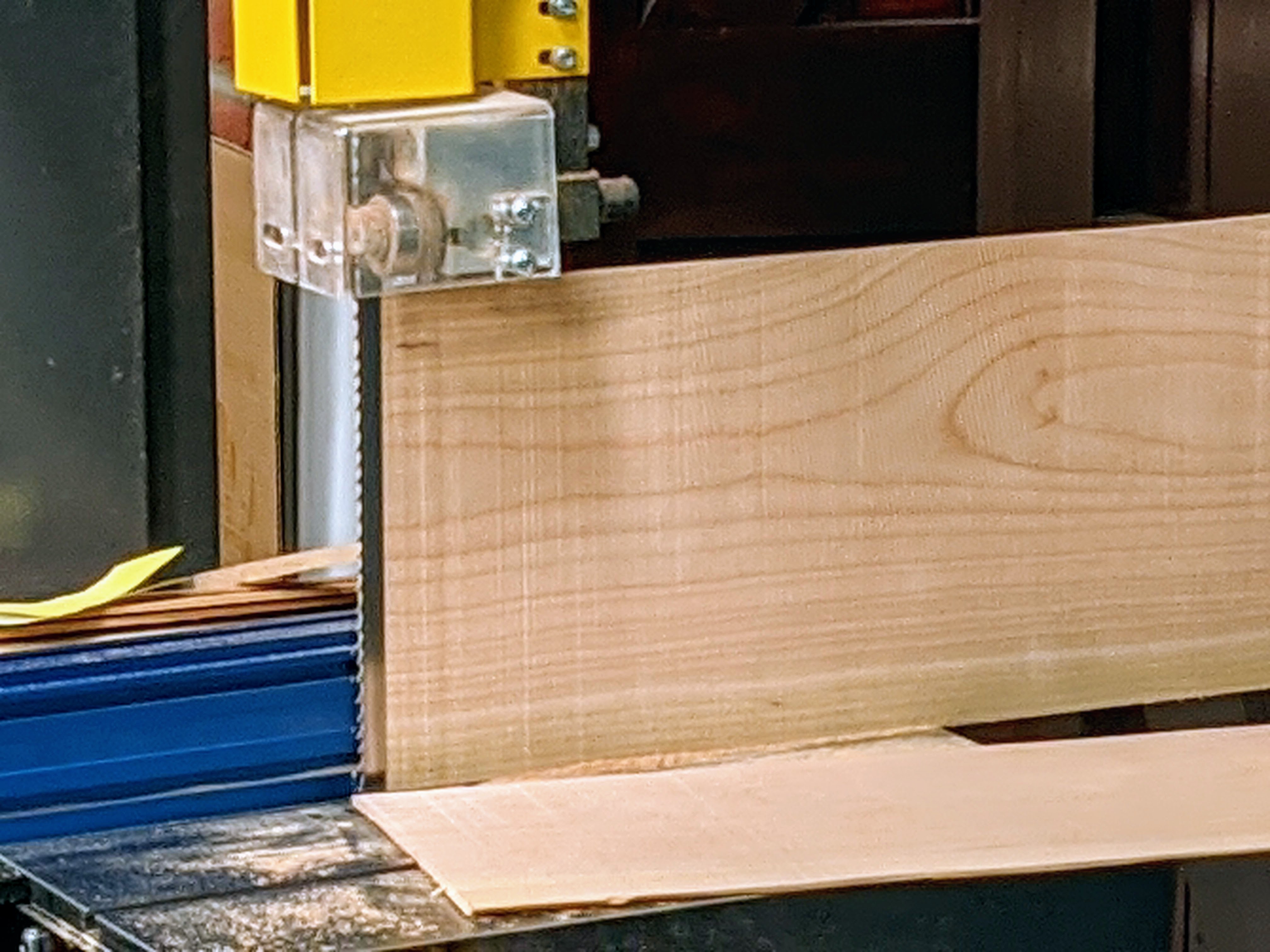

In one or two of my upcoming posts, I will show you that strategised methods will work well long term and you will become fitter and stronger and more skilled by following the strategy I suggest in the process. You must agree to increasing your willingness to sharpen more frequently and also to using a bandsaw. I would prefer not to hear from those who couldn't live without their power equipment. I am not interested in using skilless methods. My research shows that 70% of my audience could never own, use or house such equipment. We know such things exist and that people enjoy the benefits of having them but we want more bang for our buck.

Why we prefer buying roughsawn instead of off-the-shelf foursquare

It's a valid question and if you don't have machinery and equipment I would say maybe this is an option. The trouble with pre-milled wood is that it often distorts after the milling process that flattened it to create it as a workable section - such is the nature of the beast. Preparing your wood should take place as near as possible to the time you will be working it into a piece, so as to minimise any distortion that can throw off your subsequent work such as laying out and joint making. In general, we rely on the outside faces of our wood as reference and registration faces to run gauges against or hand router planes, ploughs and rebate planes etc. Always remember that would is hygroscopic - it absorbs and releases moisture constantly. This then causes the wood to 'move' and joinery constrains the bulk of such movement once done, so for those reason we generally create the joints asap to constrain it within and by the joinery.

A really good reason for buying in rough-sawn stock is the fatness of the wood. What you buy pre-planed will be sold as a one-by which means it will be the net size that's nominal in that after milling it is finished out at 3/4" (19mm). This means that you are actually buying 1" thick stock and then taking away a finished size and paying for the waste you would have had had you bought it rough sawn out of the planer. It also means that the miller fed the board through an automatic four- or five-head cutter and so took wood off from all four sides in a single pass. The economic way for business is to simply take off 1/8" on each face whereas doing your own from the rough-sawn gives options according to your size need. When I buy kiln dried material of say 1" it is usually around 1 1/16" to 1 1/8" and mostly the latter. I can often hand plane and true this rough wood to between 7/8" and 1", and sometimes even fatter depending on distortion, so I get the fuller measure this way.

I try to see my wood ahead of buying so I visit the suppliers if they welcome on-site customers and most of them do. I have not had much success with local tree fellers as log cutters and rarely find the slabbed boards stickered and stacked in good conditions. I gave up on that as it was unpredictable for me. One day you can go and there is wood and you can buy but then one building joinery company can buy up all the stock and you must wait weeks or months for a replaced stock. Your experience may well be different. I have bought enough material now to see that it can be very hit and miss and thereby unreliable.

Going to the timber suppliers is I think our equivalent to how half the population perceives a day out shopping - I always enjoy it. I also enjoy meeting my friends at the timber suppliers. As I wander through the racks I rummage around to pick out the special bits from the odd-bins that others might not want. Often, for little money, I am able to take away a piece or two if I am prepared to cut around ugly stains and wormhole for that quarter-sawn lovely I can use in small projects like boxes.

Okay! What to look for!

In the big box store, I usually am looking for something here in the UK we call Redwood pine. It's a wood I have relied on since my apprenticeship days, a wood I have loved. It is always hard to say which wood is stable and which is not because they will all surprise you at some point. You soon get used to knowing just what stable is. Stable means that each species you work with is less or more likely to distort when compared to others. Wood is hygroscopic. In a dry atmosphere, it will release any moisture to match the surrounding atmosphere. Conversely, it readily absorbs moisture from when the atmosphere contains moisture at a higher level than the wood has in its fibres. These exchanges of moisture levels will usually but not always cause the wood to change shape and size. When you buy wood from a supplier, it will almost always be dried by a forced method using a kiln of one type or another. But because it says kiln-dried we tend to think that the wood we buy is permanently dried when that is not the case at all. Wood dried down to 7% in the kiln will rarely remain at that level in most of the UK. Wood products made in Houston in southeast Texas, where the MC in the wood may have risen to well over 10%, and then going to west Texas where the desert lands are so dry, will reduce a percentage or two of moisture over a few weeks. If this happens the wooden tabletop will shrink, possibly change shape and will often end up with at least an end-grain crack.

Part III coming very soon. Here we will get to the nitty gritty of how I get my wood from roughsawn to perfected sizes for joinery and so on..

Comments ()