Prepping Wood Part I Intro

In business as a full-time woodworking furniture maker, I relied heavily on machinery to take care of the donkey work and also those masses of repeat cuts on products I mass made on a more commercial level. My product line was developed to make money and though I was careful with every piece I ever made and put myself into the quality, such work eventually became dulled and uninteresting to the point of being extremely boring. Not only that, I became soft. Every cut I made relied on a machine mostly and my hand tools came out to trim what couldn't be trimmed readily by the machine I was on. More than that, I neglected sharpening because, well, the hand tools weren't so much a part of my day anymore. The orders were coming in steadily and I was maxed out. This was a time when success was measured in money and how much of it you took in to turn a profit. You can make a million out of anything wooden. Make a million cutting boards and charge one pound more than your overall cost and you will end up with a million in your bank account when done. My becoming soft meant a softness in many ways and not the least of which was in strengths I had unwittingly allowed to go to waste. Think muscle waste, for instance. Think brain power too. If everything I did was coming off an automatic rotary cut, I had nothing to think about. I set up the machine and checked for a safe pass before pressing the on button. Everything was guaranteed! When a stack of boards becomes a thousand walking canes over a few days, or perhaps 400 cutting boards, and no handtool was used, a tedium sets in and you feel every day is the same. That was not forme.

Over a period, sanity reigned, and a shift in my attitude towards earning came from reflecting on what in life meant to me the most. I concluded that mass making for money could never give me the satisfaction that skilled hand woodworking had always given to me, but much more than that, it was the relationship to my material in its unpredictable character as well as its predictability too. With hand tools, the wood requires my constant engagement, my sensitivity and my willingness to change direction, offer an alternative effort, tool, method or technique. These were the differences and these were what I found the most interesting and sustaining. I didn't want the guaranteed outcome a machine always gave in chips sucked out through a vacuum system, I wanted my energy challenged and my effort translated into something that cost me everything. The inner me as a maker was a soul with skill. I wanted the self-discipline hand tools demanded, to own systems I'd set for myself in patterns of working, patterns that required me to keep a standard. The last thing I wanted was a machine to substitute for my complete, immersive involvement. Who can truly explain the engagement I am speaking of? It defies explanation because if woodworking is evolved to a level that it takes out almost all human effort, surely then this is the better outcome. Well, in my woodworking, no! This is not the case.

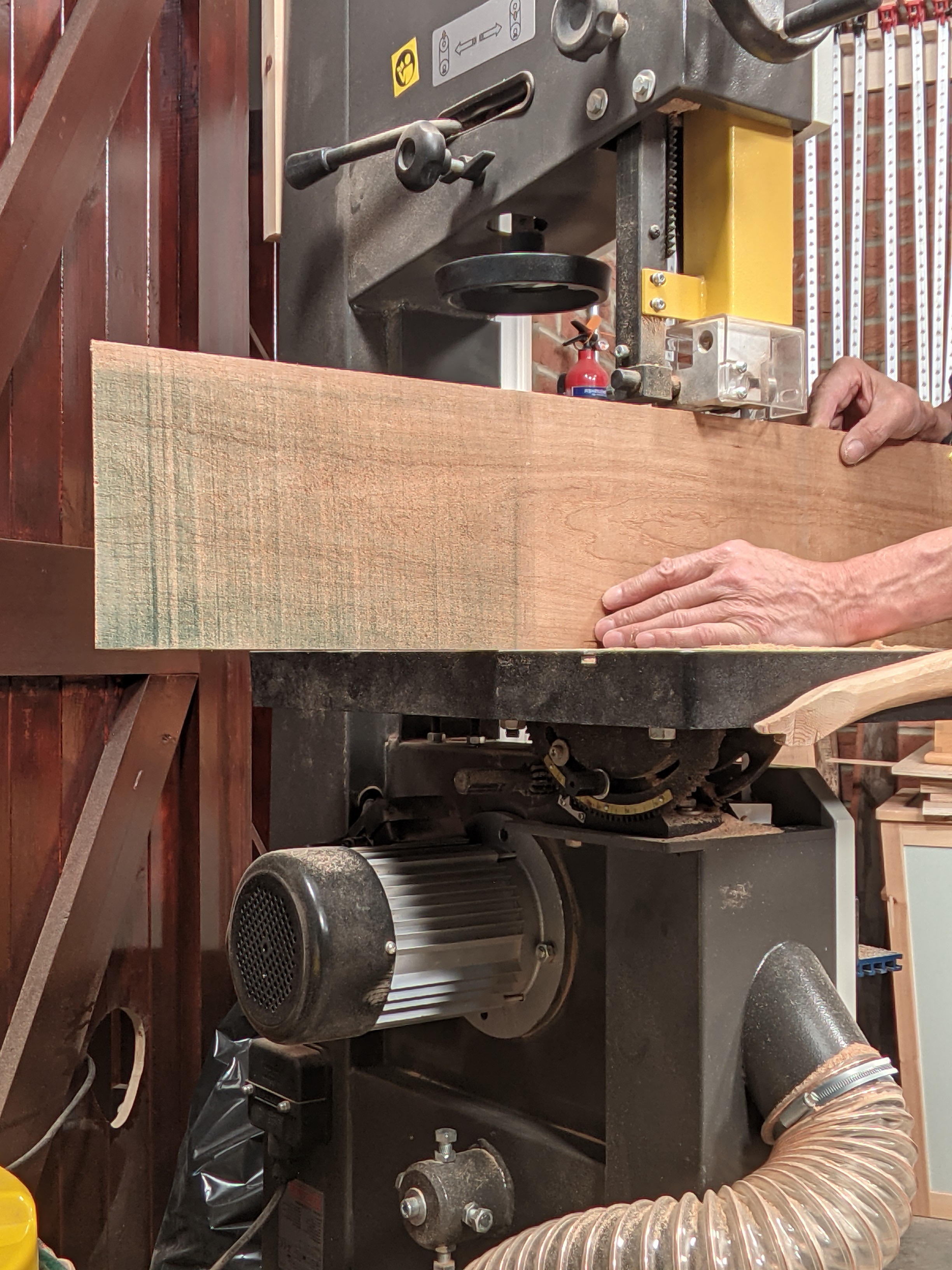

Today, the only machine I really use is my bandsaw. I also have a drill press that I have thought of taking out to free up valuable garage space for my moving around and not to install another machine, I use it so minimally. It's handy for drilling perpendicular holes, making a hundred wooden plugs and such, but is the handiness worth the loss of space it takes? I don't think so. On the other hand, the bandsaw makes perfect sense to me. More than any other machine. These last few years, since setting up the garage workspace and preparing for the sellershome.com series of pieces, I have relied mostly on my bandsaw only. I have gained weight, but not in the way you might feel negative about. My weight gain has been in added muscle mainly. My chest, legs and upper body have become more muscular because I am lifting beams and heavy boards to crosscut and prepare for the bandsaw and then used the bandsaw for roughing down large stock to workable sizes. Some sections with wane on have been 24" wide, 2-3" thick and 10 feet long. All of my work in this area is on my own. I think that this is especially important for those following and engaging with the sellershome pieces. I think I need to show what it really takes to convert the wood in safe ways. So no one supports the wood for me or lifts it with me. I use leverage and a moving table to place the wood near to alignment and then I remove any excesses first. Excesses means rotten sections, splits, wane and so on. If it is crosscutting, I use a handsaw only. This is very simple and effective, always fast and always a safe, no-nonsense way with sawdust that drops to the floor and doesn't puther into my atmosphere.

My next post very soon,maybe even tomorrow, will walk you through a very specific system I rely on to get all of my rough-sawn stock to a hand-planed finish with four standard planes and my bandsaw. I understand that some woodworkers are set up with machines for this work, but I still want to encourage everyone to do as much as they feel that they can using their bodies. The exercise is really excellent for one thing, but it so combines with developing the physical experience of moving wood, balancing, transferring, transforming and of course building all of the strengths I speak of. Of course,for some it is a question of time and for others physical limitations body wise and then noise too. Just do the best that you can and especially if you are new to hand tool woodworking and want to become skillful. The most important thing is to feel satisfaction and enjoyment.

Comments ()