Long in the Tooth . . .

. . . the Plane With Teeth

Here's another rambling from my mid-night, overtime excursions where I explore issues once common to woodworkers and write best twixt 3 am and 4.30 am thinking about the world of woodworking I live in. I make no excuses: it's who I am and have become and will be into the future for as long as it rests with me!

Today I will make again. I'm working through the booklets I wrote 15 and 20-plus years ago as is John. He is just about finishing up making five-pointed stars as I did a few weeks ago.

I think he will make the Joiner's Traveling Toolbox next and he'll enjoy that as much as I did the recent video series that just aired on woodworkomgmasterclasses.com. I am also looking forward to my next bigger build for the living room as I have some new joinery to include in the project. One of my favourite designs in recent months was the floor lamp that also had some quite unique joinery in and some of which I plan to include in the upcoming pieces for the sellershome.com collections.

Inserted into my making of things, I often discover things that might otherwise go unnoticed that I fear will then become, well, unknown. This is the amazing thing about hand-making and the hand tools we use and rely on. In my book Essential Woodworking Hand Tools, I have written about why the blades of tools are wider than the width of the plane as in shoulder planes, bullnose planes and fillister planes.

Often, mistakenly, woodworkers think that they improved on poor engineering and make the blade to match the dead width of the sole perfectly. Not the right thing to do at all! I have also explained why a router plane blade cannot be honed parallel to the underside face of the sole. . .

. . . and why square awls are specifically designed for working wood with and why they too are perhaps more essential to our work than the ubiquitous round versions not at all meant for wood.

These gems of information captivate the imagination when you are indeed in pursuit of knowledge about the hand tool world of working wood. Most of it is not needed by those dedicated to machine-only woodworking for obvious reasons. In our particular sphere of benchwork, such knowledge becomes ever-more essential as we learn to use, adopt and adapt tools specified for one task to do other tasks they were not intended for. A saw to cut thin or narrow grooves for instance. the router plane is another good example.

One of the single most essential tools used in making the White House cabinets for the Cabinet Room is yet another one that might just go unnoticed yet it is one that was used on most of the surfaces.

I was aware of it over the past couple of days as I made my rocking chair and experimented a little with glued-up components where I split the glue lines to check the efficacy of glues. I knew that too smooth a surface offers less quality to a glue line but was unsure to what degree. It stands to reason if you think about it but often, things at the bench make clearer sense. It's often not the scientific approach so much as, well, what really happens. Whereas science has its place in supporting much of what we previously just felt about this or that, I have found that many things made in the zone somehow release a working knowledge that has to come by experiencing something right there as you work. The tool I am talking about? Oh! It's the toothing plane. There it stands with its perpendicular blade looking awkward, badly designed and misaligned if not then maligned too. How can such a plane work?

I noticed that the wood sections can somehow separate when I sharpen my planes to the general extreme of over 10,000-grit. Place a chisel between the parts and hey presto the glue line seems not to hold. Though it is obvious to me it is not not likely to be obvious to all woodworkers and especially perhaps to woodworkers who never use hand tools. A surface can indeed be too smooth for good adhesion in the same way a surface can be too smooth for finish to absorb and adhere to a finished surface after hand planing. Most often, we hand toolists must roughen the surface by, guess what? Sanding! In most cases we use the term, "Let's now sand the wood smooth!" In our case we actually sand the wood 'rough'. This can be quite a revelation to those new to hand working of wood with hand planes. In most cases, I have noticed just how mind-blowing this can be to new woodworkers but then equally so to those who discover hand work over their more-common-to-them machining work where subsequent sanding is needed to remove things like planer and saw marks. In our case we rarely use sanding with abrasives to smooth what is infinitely smoother but to more to roughen the surface.

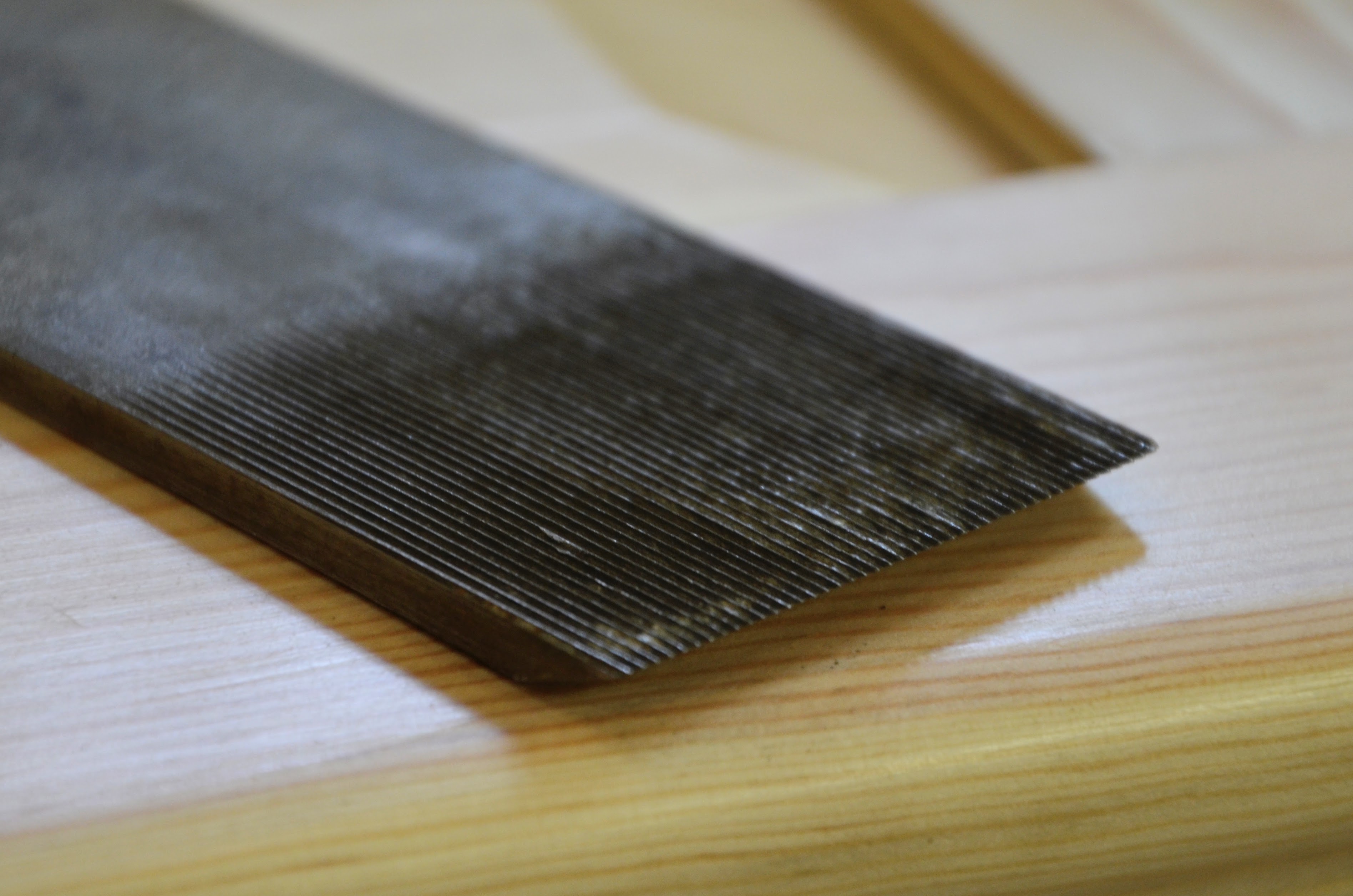

Back to the toothing plane. I do not expect a few hundred people to go out and buy a toothing plane easily or readily on eBay and especially following this article where the prices just went up exponentially and the happy eBay sellers just wondered why the prices went so high for what they described as a "Vintage block plane, rare!" The poor man's version works to give you exactly the same surface you need. I made mine in minutes from a well-used gent's saw blade. These need no special sharpening, just an occasional touch-up as you might any small saw from time to time.

Comments ()