It Takes Effort to Change

When I arrived in the USA the first thing I did was purchase a shop full of power equipment. Like most in the trade, woodworking was mostly about efficiency and efficiency comes by using machines for every cut. Though I too relied on power to expedite my work, in some ways I am likely one of a dying and disappearing generation. I was trained in hand tools alongside machines. Colleges at that time still taught and allowed only hand tool methods and no machine shops were in sight or on site in the curriculum. It was not that we received instruction from the lecturers, most of not all of them were papered experts not practical makers. They simply taught about not from. Even with just a year under our belts we probably knew more about handwork with chisels and planes than they did. It could be different today but I don't know. Do things improve with each generation?

Pocket calculators and computers were still somewhere far on the distant horizon. The www was yet to be invented and delivered and we faced all kinds of political unrest with three-day workweeks and the threat of nuclear war twixt the then world powers. What's changed? I was glad though for one thing--my craft of woodworking and making furniture seemed to me the sanest thing. I was in the throes of becoming skilled. I was launching my boat and destined for a career as a maker designer. One day I would have my own business and then I would be free. In the USA, my machine shop was 30 feet by 30 feet, but where my treasured hand tools and my hand tool workbench were kept was but the size of my present single-car garage. I quickly and readily established myself as a furniture maker in the USA and it was in the garage shop part where I did 95% of my work which achieved more and more with hand tools.

My furniture seemed different than most everyone's I knew somehow. At first, I wondered why but then I realised pieces from power equipment replicated the US 2x4 with its eased corners for comfort-use in construction. In 1985 in the UK, 2x4s still had squared off and sharp corners--built in splinter carriers. I saw that without hand tools most sections got routed with a power router to mould the edges or were rounded over with a random orbit sander and surfaces were always belt sanded and then finished with a random orbit sander. This alone muddies the water for me, even though I do also use sanders,

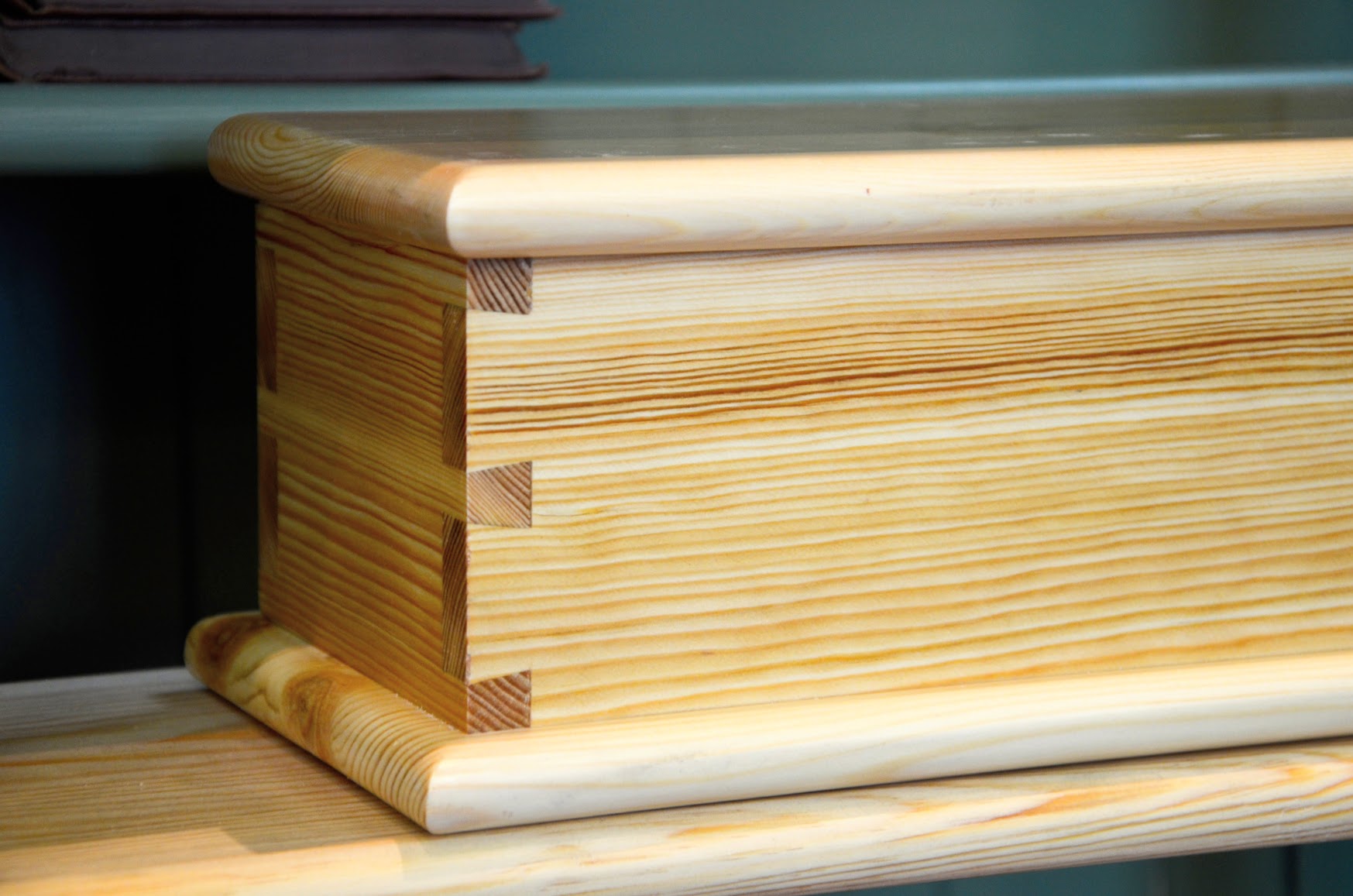

My dovetail joinery has always been hand cut. I never used power equipment to cut a dovetail and for good reason. In competitions I entered I never took second place. Why? I think mostly it was because there is a quality in hand work that stands out from the rest somehow; handwork speaks for itself. It's important to see that no one could ever look at a machine-made dovetail and say it was hand-made and, conversely, you could never look at a hand-cut dovetail and say it was machine-made. Other things affected the outcome of an overall finish and appearance. That crisp bevel on every corner of every stick of wood never became rounded by abrasive as no abrasive was needed. You couldn't get these subtle differences from a machine. The plane gives the work a crispness that sanding can never achieve. It identifies the maker as hand tool user and maker. It was the scraper and the plane, the chisel and the spokeshave that separated the work of the machine from the work of the hand toolist.

Being raised with machines alongside my hand skills for me meant choices. I could choose delivery using one or the other or a combination of both. In my apprentice days I worked with a dozen men who could create a dovetail in a few minutes by sight and with no more than three or four hand tools. I was taught the basics by them, yes, but the skills I then developed had little if anything to do with them. It was after I left them and my apprenticeship that I entered the sphere of creativity that demands investment and investigation. The questioning of how and why this or that made me think critically about what craftwork meant for me. I didn't want the easy path, I wanted to understand why I worked and what I worked for. It was not money I sought but a whole life existence. What did I value the most? Just how could I engineer my way of living and live what I believed in to be the best for me and my family. Soon I developed my own ideas and skills. I became at least as fast as others were using their machines and my neatness in execution continued to grow and grow. Skill takes time but then the satisfaction is incomparable. It was in my mid to late 30s where I needed to decide my future. I needed to ask myself whether my enjoyment creating with my hands could indeed parallel what I could produce in my machine shop where I had found myself mass making and being driven by machines. With four boys behind me, I did not want them to push stuff into machines. I trained them to work only with hand tools until they were out of their 20s. They all have a hand skill and a belief that they can make anything from wood with their own hands. My apprentices have all, all, been treated the same way. No power equipment until hand tool mastery is fully established. I think it is fair to say that in many woodworking businesses, using the machines would be seen as a mark of maturity in the same way young people might see driving a car in their teen years. Somehow such things seem apt to validate when in many if not most cases they substitute for maturity. Give someone a chainsaw and they will never drop a tree with an ax or a two-man saw. So it is with professional woodworkers. I found myself more isolated in the early days in the USA than I did at any other time in my life. When people saw me use a tenon saw they somehow turned away. That is at first! But then I got a call from a woodworker's guild in Mesquite, Texas where a small shop owner asked me if I would like to come and "show and tell" why hand tools work. Twenty men in belts and braces (suspenders US) stood in a circle around a very poor-quality workbench as I cut my twin dovetails in just shy of two minutes. There was a show of hands as several of them reached for the dovetail in unbelief. From that point, unintentionally, they were eating my sawdust. We each stood at the bench and cut a first dovetail. By the end of the morning, every man had cut his first dovetail and every man believed in himself from that point on.

Over the following years, I relied less and less on power equipment and more and more on my skills and abilities. The wood I worked offered me the greatest challenges and I had to work out how to transform wood from its rough state into a finished piece of beauty using the hand tools I owned. Using hand tools demands that you come to know your materials and your tools differently than when relying only or mostly on machines. You relate to the wood differently and you of course rely on all of your senses to make choices as you move through your projects. To compare machining wood with handwork is a silly thing to do. It would be like comparing a car driver to a runner. It was this that led me to believe that everyone could do the same as I did if I could short circuit the learning curve for them with a foundation course in hand tool woodworking. Six thousand five hundred students attended my classes over a period of nearly three decades. I proved my courses through them. Why? Not one of them ever used a machine for any part of their training. It was all handwork.

I have a special blog coming up to reflect some very recent developments and this blog post is to prepare you for that. Stay with me and we will travel a new path together.

Comments ()