Does Dead flatness Matter

Not really, but it's just a reference face and we generally need something to shoot for. What is funny is that those advocating this thing called dead flatness are the ones selling all the gear and the sooner the support gear wears out the sooner you are back for the next batch of abrasive paper, film or whatever cuts steel to the fine edge you want. Gluing abrasive to a dead-flat glass plate or granite works but then you must remove, replace, clean off and reglue more abrasive paper to keep the flatness without bumps that you need. Sheet abrasive of almost any kind will do the job and is fine to get you started but it's not nor should it be a long term sharpening solution to sharpening. Not only will it prove the most expensive option if prolonged over months and years, but it's also more the impracticality that may well not be so evident at first. in the start out, if you've accomplished sharpening a tool at least, then that can be enough appeal alone. Ultimately, what you want and need is the immediacy of sharpening. Don't be misled into believing that sharpening an edge means the edge will last for hours of use. Mostly it won't, in fact, it might well be a matter of minutes before you must return to the abrasive. That being so, better to choose an abrading system that will not need such constant replacement. Oh, and don't fall for hyperbole titles like "scary-sharp" systems. It was and always will be silly. Any and all abrasives will give you the same level of sharpness and so too any bevel of between 25-35 degrees will give you the edge you need whether it is micro- or maxi-bevel or anything in between; believe me.

Please remember that just about all magazines are primarily supported as media companies charging advertisers for adverting their wares and then too expecting the magazines to actively promote what they make be that a gardening magazine selling hosepipes or woodworking magazines promoting power routers, fancy table saws, and bandsaws. You get what you pay for and what you are paying for is at least 50% of the pages dedicated to the advertisement of stuff. At any and all woodworking shows, stores, etc it is the same. The ones pushing the planes are sales staff and not experts in anything more than making that plane look good for a few minutes. It's at the workbench in your workshop where the rubber hits the road.

I have watched the gurus you may well know and watch spend a good hour setting up the equipment to make them and their equipment look good in front of the audience. Anyone and everyone can make a plane cut any grain in any wood for a few minutes. In the reality of benchwork is where it all matters. These artificial environments are really quite unreal and not at all part of my world whether teaching or making. In my world, a plane needs to go from dull to sharp, reinstalment and reset in under three minutes. Anything else is totally unacceptable. I know, that's just me, but its the woodworking that is the most important to me. What helps me to achieve fine woodworking is a crisp sharp edge. I might sharpen 20 edges in a given day. I can't give up 10 minutes just to remove abrasive from plate glass or even have baths for slopping stones around in. Sales staff can be great actors after a few days of selling and then they can come across as really experienced in the field. I know a dozen or so of them and as it is with most people in sales, what matters at the end of the day is how much they sold. Not cynical, reality. I know some who 20 years or more ago did little more with wood than set up their sales pitch to sell planes, chisels, saws and such at the show venue and then pitch to the public. Nothing wrong with that at all. But that made them experts and in the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king. That began their careers as experts selling on the show floor not really experts in the zone of woodworking.

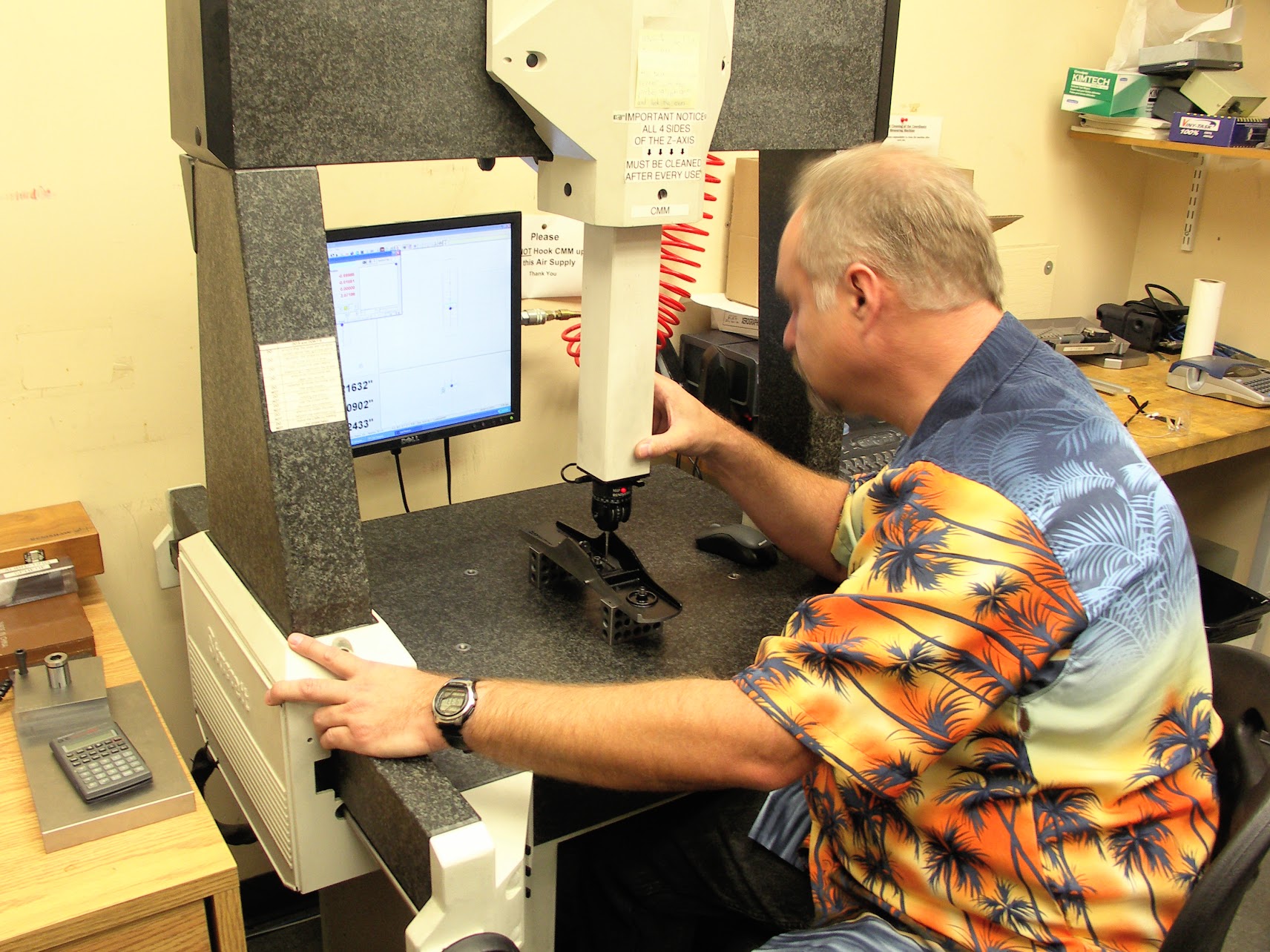

Back to the point. Dead flatness needs rarely if ever be as flat as people say or we might believe we need. Often the ambition is beyond possibility for several reasons not the least of which is having the right equipment. Visiting Lee Valley Veritas in Canada to see how their tools are made made me realise just what it would in fact take to achieve a truly flat surface. Their equipment is very sophisticated and their standards are very high to match.

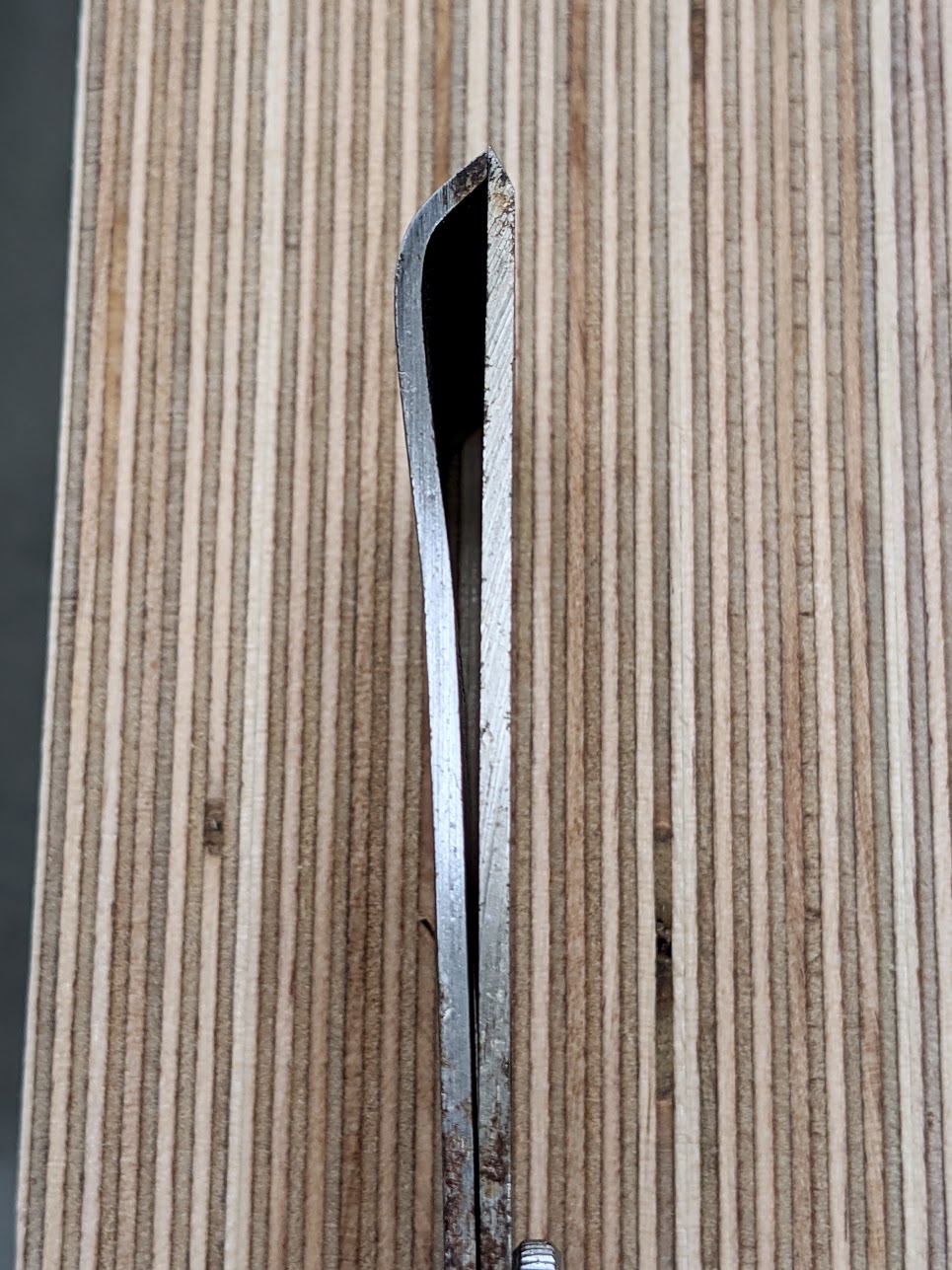

In fact, it is almost impossible for anyone with the kind of equipment we have access to use to get a meeting face to a bevel truly dead flat. That fine edge is indeed crumbling even as we sharpen, albeit very fractionally, and perhaps to a level that the edge fracture cannot be seen by the unaided eye. The larger the abrasive you begin with the more the leading edge will indeed rounded by fracture caused by the particulate itself. Our reducing the particulate size in step-down abrasive sizing helps. Of course, it does. But no matter, it still results in the leading edge appearing slightly rounded but rounded it is, by degree at least.

The two areas we generally look at for sharpening are plane irons and chisels. Most of us do not use draw knives and the spokeshave is a plane with side handles instead of inline totes anyway. All planes offer the cutting edge of the iron at an incline anyway. Never is the flat side against the wood as such. Bevel-up, bevel-down, all plane blades present the underside face if the cutting iron bevel or flat at an angle between 12-15-degrees. Few might realise there is so little difference between the two plane types. Also, as a practical issue, these edges fracture ALL the time. Mostly it is edge fracture not wear that turns the edge from crisp sharpness to unusable. The longer you procrastinate the more work it takes to get nearer to the sharp edge again. This breakdown of quality is in your hands. I rarely wait until the edge is dulled for more than a few strokes if I even get a hint of being near to that point. Perhaps this will give you an idea of why paper and film abrasive is not really a long term solution for the total sharpening option.

OK. The conventional bevel-down plane held by lever caps with cap iron (not really called chip breakers because they don't break chips) sandwiched in between need not be dead flat across the large underside flat face of the cutting iron. Why on earth would anyone say such a thing? Well, with good reason, I do and always will.

The relationship between the cap iron and the cutting iron is critical to bevel down planes with thin irons, even if the thin irons have indeed been replaced with so-called thicker irons. Cutting the side off a plane helped me to see the reality the power of the lever on the lever cap had at this critical juncture in the plane iron assembly beneath it. The lever at the top of the lever cap is powerful. Pressing the lever from open to close is a transfer issue whereby the foredge at the lowest point or edge of the lever cap applies force along the hump of the cap iron that in turn applies pressure along the whole of the flat face of the cutting iron to press it wholly to the leading edge of the rear part of the plane's sole a d then too the lower area of the bed of the frog right up as close as possible to the cutting edge of the iron.

Even if the cutting iron was twisted, hollowed or bellied by a great amount, which they rarely ever are, it could not resist the pressure to conform to the frog by the single pressure from the lever on the lever cap. If the frog is flat along its width by the leading edge, the blade will end up flat too. On bevel-up planes, the fore-edge of the cap is forced down by applying pressure via the knurled bolt and the reverse cantilever that pivots via the central setscrew. Again, the force you apply easily conforms a twisted, bellied or hollow iron to the mating surface.

Now on chisels. Whereas I might admit that a dead-flat face is of some value, that is rarely essentially the case in terms of using them and actually it is as I said earlier, rarely possible for anyone with the kind of equipment we have access to use to get a meeting face to a bevel truly dead flat. That being so, we should rethink why we actually need the chisel to be so dead flat. Let's say that 50% of chisel work is chopping and the other half is paring. In both cases, dead flatness is not really needed. Experience through the years tells me that we constantly micro-adjust the presentation of the chisel to the task by what we feel and see as we use it.

Normal work is undertaken by raising and lowering the handle end until the chisel bites. Very rarely do we need a chisel to pare when it is level with the surface of the wood. We create the cutting dynamic by equalling out the top and bottom pressure as we push the cutting edge into the wood be that with the grain or across it. Whereas we may well pare a plug level to a surface, even in this we rarely can without elevating the handle a degree or two to equal out the pressure above and below the cutting edge to effect the cut evenly with pressure to the top and underside. If that is the case, and it is, then let's just aim for flat without sweating it.

Chopping mortises or recesses for inlaying wood or hardware is really the same. No need for dead-flatness here either.

Let's break out! Take a step away from legalism and just enjoy sharpening to near enough. Rethinking from my youth and watching skilled men just sharpen up and get on with their work was magic. We can have that too. If you do enjoy extensive methods for sharpening though, just carry on. As long as you enjoy it what does it matter?

Comments ()