Sharpen More Often

There is no prescription for how often a saw goes dull or how often you should need to sharpen this or that saw. Truth is for most of us, in reality, is that we are more likely to sharpen less often than too often. The reason for this is that tools still cut surprisingly well when they are surprisingly dull. Experience working with people learning has shown me just how far they fall short and how much they overwork an already dulled cutting edge to optimizer their worktime. Unfortunately, it's quite common to think that it's a choice they make and that they simply need to expend more of their own energy to expedite their work. What they don't realise is that many things are sacrificed by their unwillingness to sharpen up.

Here's the thing. Planing my oak this week I sharpened two planes half a dozen times. Once I sharpened one of my planes within five minutes of a previous sharpening. Planing woods like oak are not too demanding. Some times you plane an oak board 8" widen and the shavings peel off like super long and continuous onion skins two feet long. The board feels like glass and, well, no matter how often you do this in a lifetime, it is still exhilarating; and so it should be. It speaks of having put all things into order, the sharpening, the adjustment, the choice of direction in planing and so on.

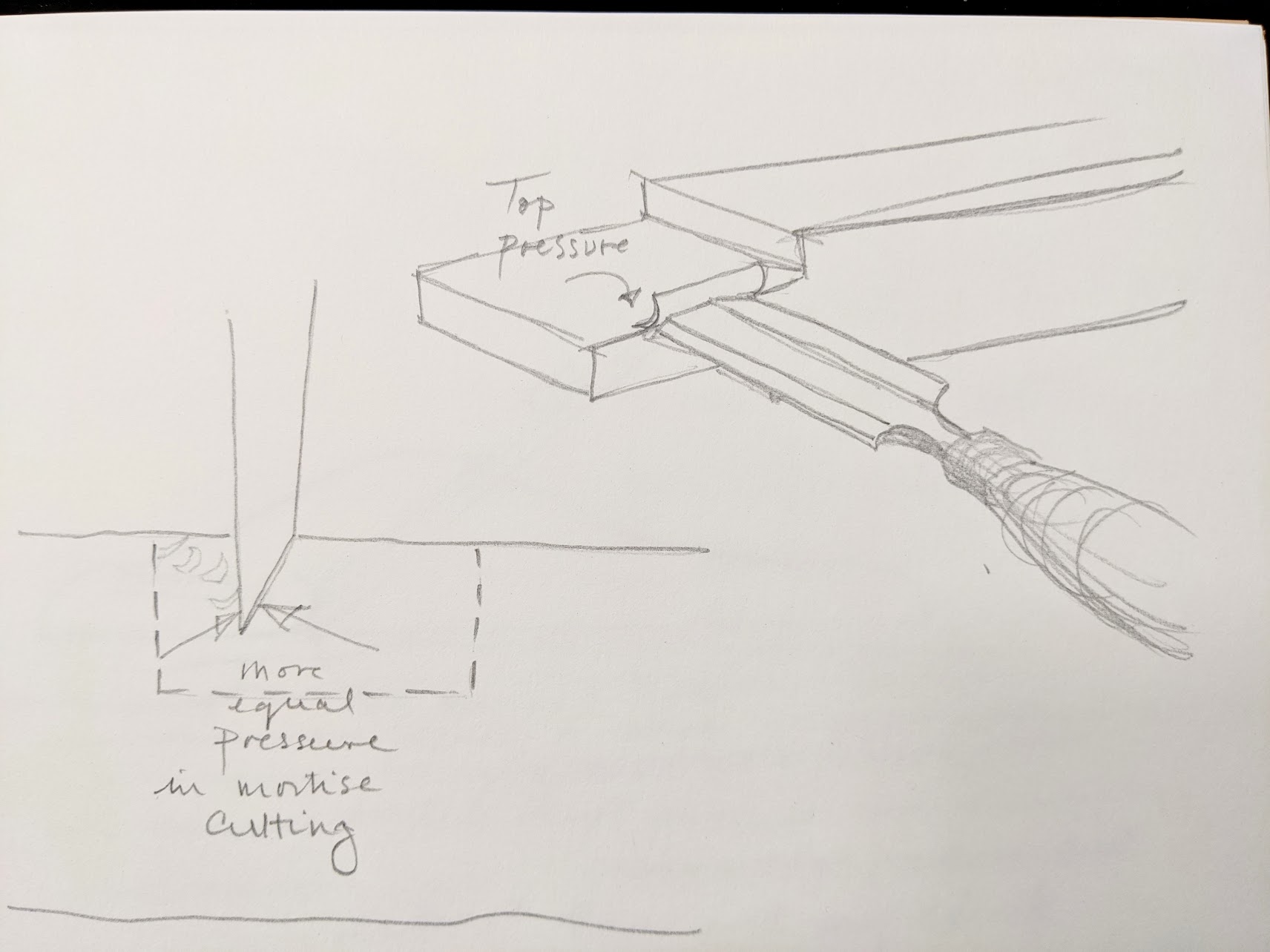

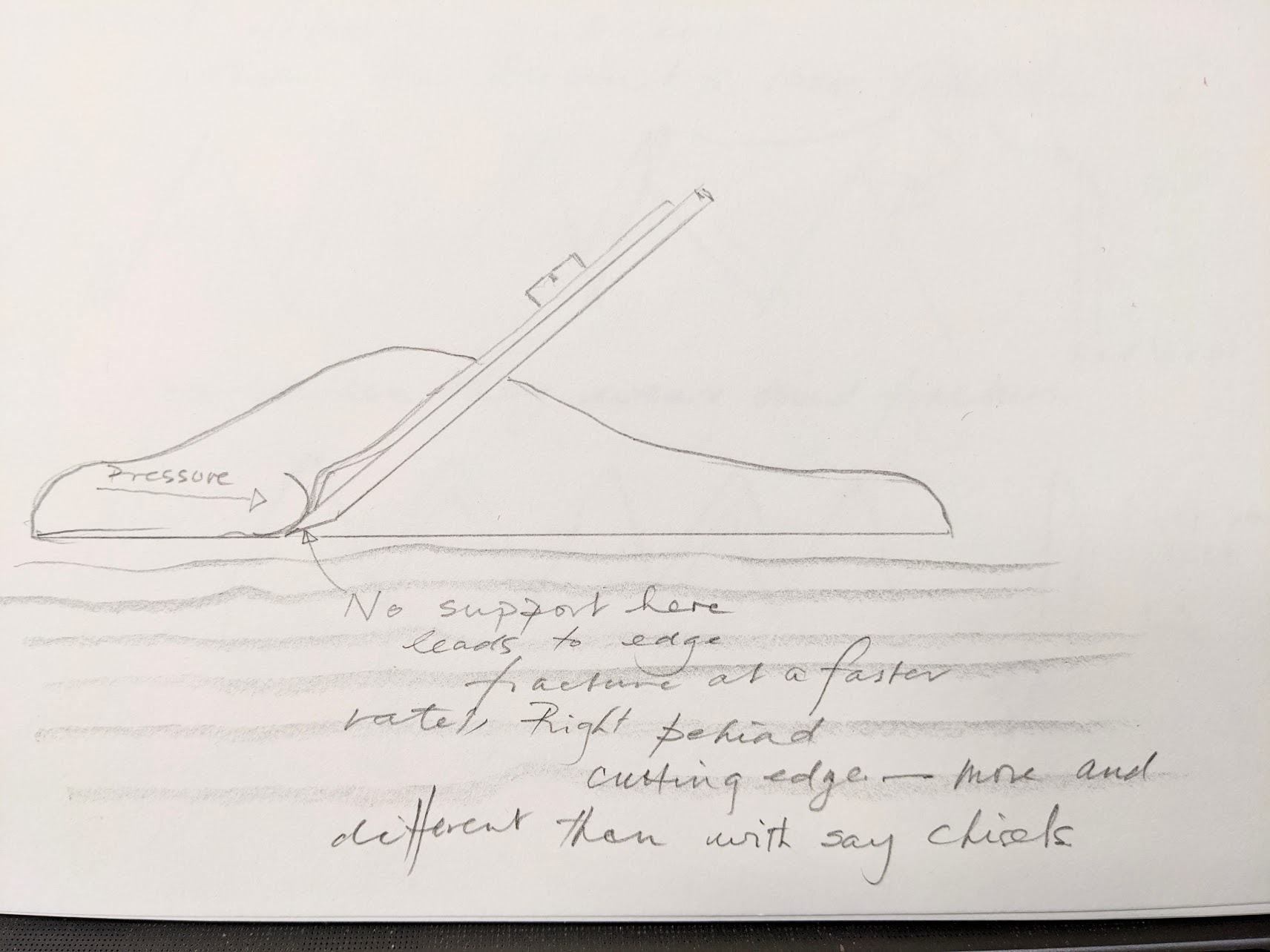

Even though I sharpen up very often, I am always conscious of how much the cutting edge dulls in planing. There is something in the planing action that is so very different than say chiseling, be that chop cutting or paring. In my view, planing dulls an edge far more quickly than chop cutting and paring. I believe it is something to do with the angle of presentation whereby the plane iron, at it's fixed elevation of around 45-degrees, hits the wood with so very little back support directly behind the cutting edge but perpetually at the same angle every time in 90% of action except when a slight skew this way or that alters it. but then added to that there is a necessity to plane areas of wood that chisels might more rarely touch. Knots, difficult grain and so on. The plane generally makes successive passes a second or so apart and many times. On the other hand, perhaps 80% of chisel work is chopping and 20% is surface pare cutting. Either way, the chisel is usually approaching the wood very differently than the plane. Chopping is very near to 90-degrees, pare cutting across the grain sideways as in paring the face of a tenon from the side is again at 90% or slightly elevated a few degrees or so. When the chisel is presented to the wood there is often higher pressure to both sides of the cutting edge which equals out the pressure on the steel. So, in general, we must sharpen up regularly without prevarication or all too much reasoning if we want the surfaces to be in constant good order. These are just thoughts but good thoughts because when we see this we query less the need to sharpen our plane and get on with it. It is nothing for me to sharpen up ten times in a day and I don't find it at all wearisome. Self-discipline is a positive thing.

In saws, there is a dynamic that happens we seldom consider in our early days working wood. We tend to think that a saw should stay sharp for months and indeed saws will often keep going for weeks and months depending oof course on how much usage they get. Here again, we tend to ask the question of how often should a saw need sharpening without considering the impact of materials on the saw and then too the work it will be used for. Woods high in silica will dull the saw and any cutting edge much more quickly. Woods with contrary growth rings of hard and then soft side by side can indeed be the very worst.

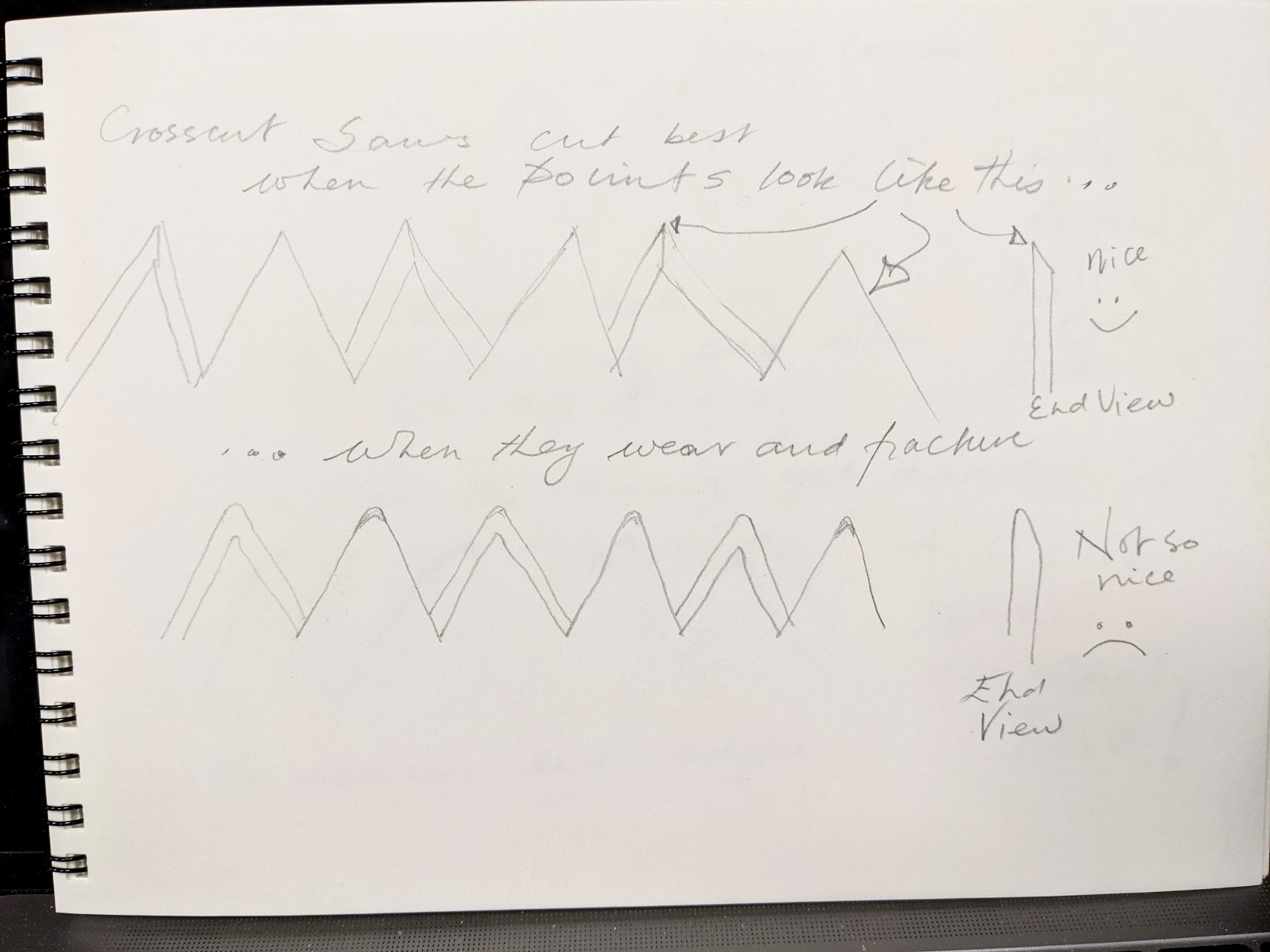

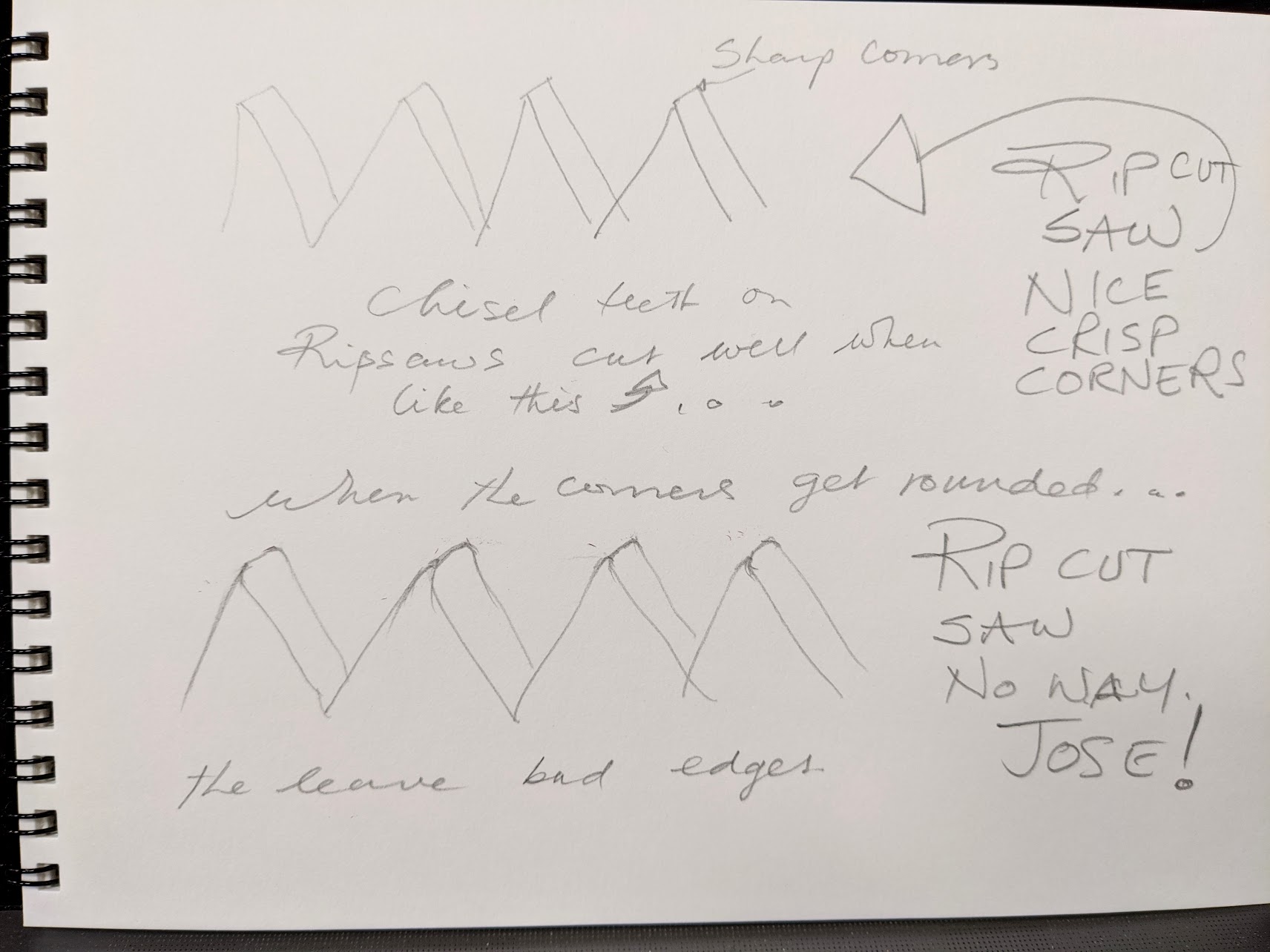

Some soft-grained woods seem to cling to the saw plate while other woods known for hardness and density seem to allow slicing like a hot knife through butter. There is no set answer for this but let me say yet again most if not all woodworkers tend to procrastinate when it comes to sharpening their saws and the reason is that they do not realise that the saw teeth do not wear as in water of a stone wearing but more a fracture and a fracture at particular points (no pun intended) The pinnacle points of crosscut teeth will not retain their sharpness as long as the wider chisel-points of a ripsaw teeth because, well, the very points themselves as so very fractious. These three-sided pinnacle points have very little to support them and it is the points that simply break off to a greater or lesser degree. And it needs only be a very small amount to make the saw less efficient. Both rip- and cross-cut saws need a regular touch up. A single half-length pass through the gullet of a saw strokes the surface and restores the cutting edges whichever the saw type. I use my rip tenon saw for the cheeks of tenons and then the gent's saw for the shoulders. If I touch up both saws before the work begins, not only do I get the best surfaces and the crispest corners or shoulders, I am also less likely to need to do any remedial work of any substance. The knifewall and the freshly sharpened saw go hand in hand to perfect shoulder lines.

Regular sharpening during any project should be standard practice but not an obsessive-compulsive thing. Yes, I know there are those out there that just love to do that, but these are not the ones I am encouraging to sharpen. It's seeing the need for sharpening on a regular basis without waiting until they don't work well that's so important and whereas it does make the work easier and more pleasant it's more the result we want from the discipline. With saws, we tend to forget that it's the sides of the plate that we are working on so that we get the shear-cut. If the corners of the teeth are worn, then the saw moves laterally away from the knifewall or cut line with each successive cut, making the shoulder-line or surface we are cutting rounded albeit on a small scale. This can lead to what looks like a shadow on the joint line

Comments ()